Restoring the Common Ground of American Citizenship: Why Lincoln is at the heart of America, and Teaching American History

Lincoln has always been central to the work of Teaching American History. For example, the master’s degree program that is part of TAH has a required course on Lincoln and we regularly offer a multi-day seminar in Springfield, Illinois on the Great Emancipator.

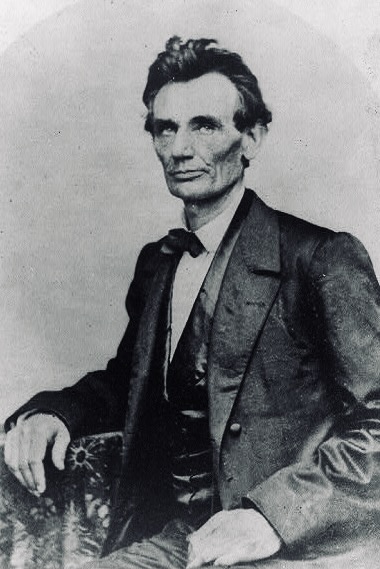

It makes sense that America’s greatest president and statesman is central to a program devoted to increasing understanding of American history and politics. There are two reasons in particular, however, for the close connection between Lincoln and TAH.

First is his example: TAH consists of document-based seminars aimed at improving understanding of American history and politics, in order to improve the practice of American politics. Lincoln’s Peoria speech is many things, but among them, it is a fine example of using primary documents to understand American history and to try to change the way Americans thought about their history, in order to improve American politics. The Cooper Union Speech is another example of this.

The second and most important reason we study Lincoln is that our own purposes are inspired by his. Above all, Lincoln worked to restore the common ground of American citizenship. The Civil War, of course, was the greatest evidence that Americans in Lincoln’s time had failed to stand together on common ground. In our own time, some have argued that our divisiveness threatens another civil war, so restoring common ground remains essential. In truth, however, restoring common ground, bolstering civic friendship among Americans, is always the most important task of American statesmanship.

The perennial importance of finding common ground derives from the problems inherent in America’s fundamental political principles, equality and liberty. Lincoln’s words and deeds are the best guide both to understanding these problems and to overcoming them.

What are these permanent problems?

What Lincoln understood was that our fundamental principles of equality and freedom can easily be misunderstood and lead to inequality and tyranny, precisely among some of those who are most committed to equality and freedom. He also understood that civic friendship is ultimately the only way to counter the harmful tendencies in America’s political principles.

In Lincoln’s time, the tyrannical possibility inherent in liberty was most easily seen in the case of slavery. Some people thought that their liberty—their rights—included the right to enslave other humans. Lincoln argued this was not an exercise of liberty, but an act of tyranny.

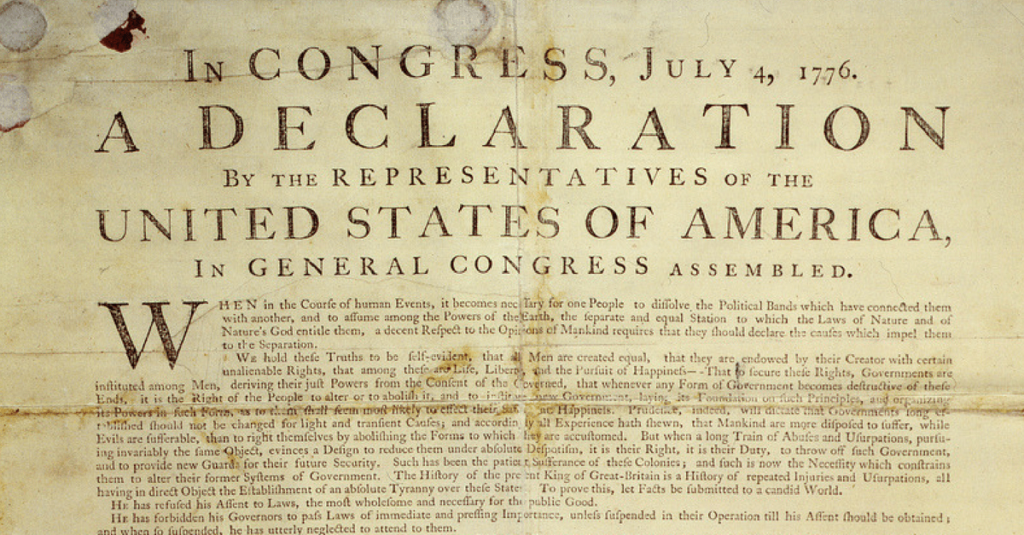

Slaveholding was not a right in any sense, but a wrong. It was wrong because “all men are created equal.” Therefore, no human has a right to rule another human without consent. Equality is the foundation of our liberty, therefore, and no act of liberty—no exercise of rights—can contradict human equality without ultimately contradicting or undermining itself. As Lincoln showed, there was no argument that justified enslaving Africans that did not also justify enslaving Europeans.

We can generalize what Lincoln argued about slavery by saying that we have liberty, we have rights, but those rights must be curtailed in certain ways so they do not infringe on the equal rights of others. Some have argued that the common ground of American citizenship is just this: the respect each of us has for the rights of others that leads us to accept some curtailment of our own rights. This curtailment should not extend to the loss of our rights, of course. That, as the Declaration of Independence tells us, would justify revolution. But some curtailment or accommodation is unavoidable. It would be hard for us all to stand on the common ground of American citizenship, if we were all insisting on the unconstrained exercise of our rights. Many Supreme Court cases are about this issue: the claims of rights that Americans make and how those claims are to be resolved when they conflict.

The fact remains, however, that as we stand on the common ground of American citizenship, we jostle each other. As we jostle each other, we learn that self-government requires a certain vigilance in protecting our rights. The dark side of this vigilance is that it can become hypervigilance and even a kind of paranoia about threats to one’s rights and to self-government. Such paranoia can lead a majority to ignore the rights of a minority and create opportunities for demagogues. Or demagogues may stoke fears about threats to rights creating the paranoia that justifies their seizure of power. In both cases, devotion to liberty can lead to tyranny.

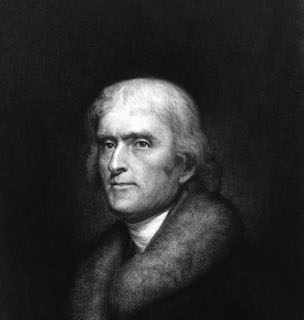

The ever-present danger to liberty from a hyper-vigilant regard for rights suggests that mutual respect for the rights of others while necessary for the perpetuation of republican government, is not sufficient. Respect for rights, especially one’s own rights, needs to be tempered. To prevent hypervigilance and paranoia, citizens need to trust one another. They need to feel civic friendship toward their fellow citizens. This is why, after perhaps the most divisive election in American history, Thomas Jefferson began his First Inaugural Address by appealing to “friends and fellow citizens,” (the phrase “fellow citizens” occurs 7 times in the short speech). It is why he called on his fellow citizens to make “common efforts for the common good,” and claimed that the Republicans and the Federalists, who had recently been at each other’s throats, were really “brethren of the same principle.”

The need for fellow citizens to share more than a concern with rights is why Lincoln closed his First Inaugural Address by saying:

We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

The appeal to civic friendship and the common good is thus a necessary counterweight to the centrifugal tendencies of the individualism embedded in the rights that the Declaration of Independence champions.

If we see that liberty can become and even tends to become tyranny, what about equality, the most fundamental American political principle?

To see the problem with equality, we may consider the Declaration of Independence.

If it is self-evidently true, as the Declaration claims, that all men are created equal, why did it take so long for humans to establish a political order on this self-evident principle?

Jefferson gave two answers. First, what he called monkish superstition and ignorance had blinded people for centuries. Kings, priests, and nobles got people to believe that government, like most important things in life, was a mystery that only they could deal with. They could deal with it, or had the authority to try, because they had a special relationship to God and thus special access to necessary knowledge that most men and women did not have.

According to Jefferson, the solution to the pretentions of kings, priests, and nobles was the spread of the light of science. Science promises that all human beings can know the causes of all things. As science spreads, the power of kings, priests, and nobles would disappear, thought Jefferson, because their claim to have knowledge no one else has would be shown to be false. To encourage the spread of the light of science, Jefferson advocated free speech, a free press, and public education.

Spreading the light of science was difficult, however, because kings, priests, and nobles and those who profited with them were self-interested and fought to keep people in the dark so they could take advantage of them. Thus, Jefferson’s second answer as to why until 1776 people did not accept the self-evident truth of human equality was the self-interest of kings, priests, nobles and their sympathizers.

The solution to this problem, Jefferson thought, was to control politically the self-interest that obscured the self-evident truth of human equality. The need to control self-interest meant that the American revolution had to be a moral as well as political revolution.

Jefferson sought to control self-interest by making farmers the basis of his republic. Leading simple lives, such people would not have the opportunity to indulge their self-interest, would therefore be virtuous, and would not corrupt the republic. Those who were not poor farmers, those Jefferson called the natural aristoi, would be educated in virtue and honored for their public spirited service.

When some people thought about the moral requirement of a republic based on equality—controlling self-interest—they thought, unlike Jefferson, that it required the elimination of self-interest or, in other words, a transformation of human nature. These were the people who were committed to moral reform, even perfectionism, in ante-bellum America. Their purpose was to rid the world of self-interest and vice. In the ante-bellum years their principal target was slavery and slaveholders. This was a Christian movement, but for many Americans, maybe most Americans, in 1776 and for a long time after, the American Revolution was a Christian movement. This was the view of John Quincy Adams, for example, although Adams was too aware of the ways of the world and man’s fallen condition to indulge in the reformist enthusiasms of ante-bellum America. He was even a late convert to the most important of these reform movements, abolitionism.

The moralism characteristic of the ante-bellum reformers has proven to be a perennial of American politics. When Woodrow Wilson asked for a declaration of war, he emphasized that the United States was not acting out of self-interest and spoke with moral condescension of autocrats. They did not deserve to be part of the world that Wilson wanted to re-make. Theodore Roosevelt spoke of the “malefactors of great wealth” and their “evil-doing.” FDR, in a number of his speeches, castigated the self-interest of the rich. This moralism continues in our own day. Whereas Jefferson blamed the self-interest of kings, priests, and nobles for threatening equality, today some blame the self-interest of corporations, billionaires, and so-called “special interests.” The antagonists have changed, but the argument has not.

For a long time, moralism was a problem principally of progressives like Wilson, Roosevelt and FDR and their followers. About 50 years ago, moralism emerged or re-emerged among conservatives, again in a Christian form. Now there is a moralistic streak in the currently most energetic form of conservatism, national conservatism.

Why is this moralism a problem?

Moralism, as Lincoln suggested in his Temperance Address, causes a divide among fellow citizens. For example, what some refer to today as “culture wars” are in fact disagreements over moral principles. Moral antagonism also feeds the paranoia we spoke of before and undermines mutual respect of rights. Would you allow those you see as evil doers liberty to do their evil? Would you respect their rights? In its most extreme form, moralism leads people to see their opponents as morally inferior and thus inferior simply. Moralism is thus the enemy of equality and only equals can be fellow citizens.

The survival of free government does require limits to self-interest. But if government is legitimate and free only when based on the consent of the governed, then free government must be based to some degree on ignorance and vice and self-interest, because to some degree all men are ignorant and vicious and self-interested. Anyone who claims not to be or sees self-interest operating only in their political opponents is an enemy of equality and liberty and thus a potential tyrant. Embracing free government means not just a mutual respect for the rights of others but also a mutual acceptance of our fellow citizens’ ignorance and vice.

The solution to the tyrannical tendency of liberty was civic friendship as a necessary counterweight to the hypervigilant protection of rights. It turns out that the solution to the tyrannical tendency embedded in the idea of equality is also civic friendship or an acceptance of our fellow citizens, faults and all. “With malice toward none; with charity for all,” as Lincoln put it in his Second Inaugural Address, should be the motto of all who love and wish to preserve free government.

As we said, the great task of Lincoln’s political life was to restore the common ground of civic friendship among Americans. That remains the purpose of TAH as well. Achieving it remains as important today as it was in Lincoln’s time.

David Tucker is a Senior Fellow at the Ashbrook Center and General Editor of TAH’s Core Document volumes.