Summer MAHG Course Examines Influence of Political Rhetoric on Citizens' Choices

How does rhetoric shape citizens’ understanding of the political choices they face? In the political contests of our history, which arguments have exerted greater influence over outcomes: those that are rational, or those that are rhetorical? These are some of the issues teachers will consider during a summer residential course on “American Political Rhetoric” in the Master of Arts in American HIstory and Government program. Professor Abigail Vegter of Berry College will teach the course.

“Spanning speeches of George Washington to those of Donald Trump, the course will consider how the tools utilized by political actors teach us something about society at that time,” Vegter said. “We will both read and listen to audio recordings of key speeches throughout our history. By reading Lincoln’s Temperance address and watching Obama’s 2004 Democratic Convention Address, we will explore the rhetoric of unity and division. We will utilize both Washington’s and Kennedy’s inaugural addresses to trace how civil religious language has impacted political rhetoric over time. As a class, we will assess rhetoric and new media to determine how political communication has and continues to change in our American context.”

Vegter’s Research Bears on Rhetoric in Recent History

Vegter’s own research interests have prompted her to consider particularly fraught uses of rhetoric in contemporary politics. She studies religion and politics, especially the intersection of religion with the political controversy over the Second Amendment. She writes about “the relationship between religion and gun ownership, particularly looking at the role of identity in shaping policy attitudes and the policy process.” She used a variety of social science methods in writing her dissertation, Faithful Firearms: The Role of Religion in Gun Owner Identity, Gun Policy Attitudes, and Gun Policy Adoption. She also writes about morality policy, LGBTQ+ politics, and new methodological approaches to studying interest groups.

As Vegter points out, rhetorical appeals involve a two-way process: “At any given moment in history, our methods of political communication reflect the personal values of decision makers and the culture of our political world.” The appeal a leader makes must not only assert his or her own opinions; it must connect to the desires and values of the voters appealed to. Yet voters’ desires and values are mixed. As Lincoln suggested in his First Inaugural Address, human beings at times respond to the promptings of their “better angels,” at other times to arguments that are rationally or morally flawed.

How Rhetoric Reinforces Reason in Politics: An Example

Sometimes a powerful rhetorical argument is needed to elevate the rational and moral choice over what seems to be the commonsensical choice. Eighth grade teacher Melanie Stuthard provides an interesting illustration of this phenomenon.

When Stuthard’s students take up the Kansas-Nebraska Act, she asks them to consider the idea of “popular sovereignty.” This, of course, was Senator Stephen Douglas’s solution to the problem of whether slavery should be allowed to enter the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. He argued that those living in those territories should vote to decide the question. Stuthard directs students to look up the dictionary definition of popular sovereignty. Then she asks them to write a response to the question: “In your opinion, is popular sovereignty an acceptable solution to the issue of allowing slavery into the new territories? Explain your answer.”

“Almost all of my students respond, ‘Yes, of course. You should always decide things by voting. That’s the democratic way,’” Stuthard says. Then she asks students to read an excerpt of Lincoln’s Peoria Address:

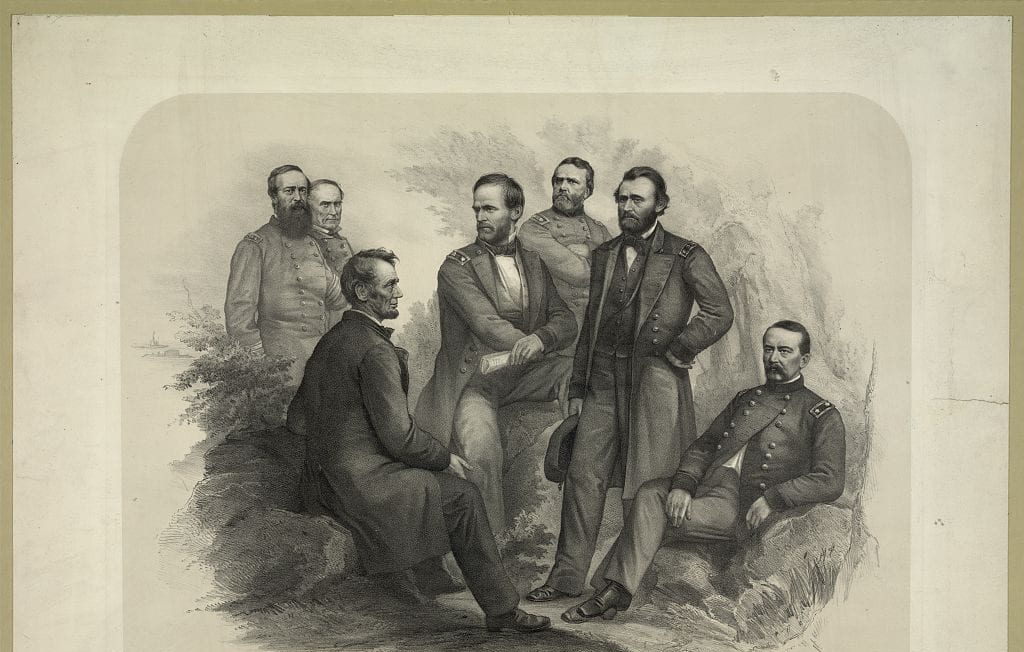

The doctrine of self-government is right—absolutely and eternally right—but it has no just application, as here attempted. . . . If the Negro is a man, is it not to that extent, a total destruction of self-government, to say that he too shall not govern himself? When the white man governs himself that is self-government; but when he governs himself, and also governs another man, that is more than self-government—that is despotism. If the Negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that “all men are created equal;” and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another. . . . Well, I doubt not that the people of Nebraska are, and will continue to be as good as the average of people elsewhere. I do not say the contrary. What I do say is, that no man is good enough to govern another man, without that other’s consent. I say this is the leading principle—the sheet anchor of American republicanism.

— Abraham Lincoln, Speech on the Repeal of the Missouri Compromise, October 16. 1854

Afterwards, Stuthard’s students write responses to another set of questions:

What does Lincoln say is the “sheet anchor of American republicanism?

[When Lincoln says,] “My ancient faith teaches me that ‘all men are created equal,’ to which founding document (the Declaration of Independence or the Constitution) is he referring?

Lincoln believed it was the job of the federal government to keep slavery out of the western territories. Do you agree with Lincoln, or do you think Douglas was right to let the people decide? Explain your answer.

— Melanie Stuthard, “Unit 5, Slavery Divides the Nation,” A Collaborative 8th Grade US History Textbook

“Now students say, ‘Oh my gosh, Douglas is totally wrong! Lincoln is right!’ Students realize that you cannot vote to approve the enslavement of other people; doing so undermines the very logic of democratic government.”

The Power of Rhetoric Today

Stuthard realized that even today, students’ unexamined assumptions about voting and majority rule would incline them to accept Douglas’s argument for popular sovereignty at face value. They needed Lincoln’s help to see the falsity of Douglas’s policy. In 1854, when racial prejudice was deep and widespread, citizens needed even more powerful persuasion to see what was wrong with Douglas’s arguments.

No doubt teachers in Vegter’s course will examine many rhetorical challenges comparable to the one Lincoln faced. Because the course on American Political Rhetoric will cover even contemporary political speech, teachers of both history and government should find it relevant to their students’ interests and their own teaching goals. Teachers in TAH programs often affirm a goal of helping students learn to think critically about the news they consume. Learning to analyze the logical implications of rhetorical appeals is an essential step in this process.

Vegter will teach the course—HIST 631 4A / POLSC 631 4A: American Political Rhetoric—during the fourth session of the summer residential program in Ashland, from Sunday, July 16 to Friday, July 21. You can read more about it, and examine the syllabus, here. To inquire about the Master of Arts in American History and Government program, visit this page.