The American Revolution: Robert McDonald's New CDC Volume

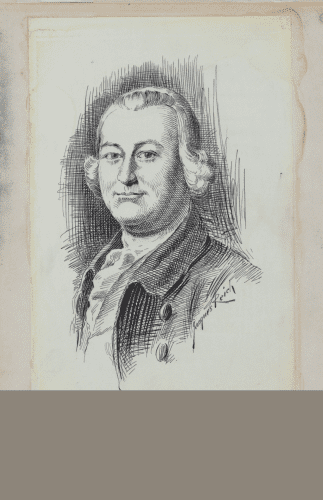

On July 4, 2020, the 244th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, a new volume in Ashbrook’s Core Document Collections will appear: The American Revolution. Robert McDonald, Professor of History at the United States Military Academy at West Point, edited the collection (which is available for pre-order only through TAH). McDonald frequently teaches the Revolution as Visiting Professor in the Master of Arts in American History and Government program. Author of Confounding Father: Thomas Jefferson’s Image in His Own Time (University of Virginia Press, 2016), McDonald has edited three other studies of Jefferson as well as Sons of the Father: George Washington and His Protégés (University of Virginia Press, 2013). “I had a lot of fun putting the document collection together,” McDonald said, as he gladly answered questions about the remarkable story the volume presents.

On July 4, 2020, the 244th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, a new volume in Ashbrook’s Core Document Collections will appear: The American Revolution. Robert McDonald, Professor of History at the United States Military Academy at West Point, edited the collection (which is available for pre-order only through TAH). McDonald frequently teaches the Revolution as Visiting Professor in the Master of Arts in American History and Government program. Author of Confounding Father: Thomas Jefferson’s Image in His Own Time (University of Virginia Press, 2016), McDonald has edited three other studies of Jefferson as well as Sons of the Father: George Washington and His Protégés (University of Virginia Press, 2013). “I had a lot of fun putting the document collection together,” McDonald said, as he gladly answered questions about the remarkable story the volume presents.

How did you decide which documents to include in the collection?

The volume tells the story of events between 1761 and 1783. John Adams famously said the revolution began 15 years before a drop of blood was shed. The first document I included is James Otis’ 1761 argument protesting the Writs of Assistance issued by Great Britain. We generally think that American resistance arose when Britain imposed new taxes on the colonies to help recoup the costs of the French and Indian War. Britain did that; but first, it tried to enforce existing tariffs.

Writs of Assistance authorized warrantless searches of colonial homes, warehouses, and ships for smuggled goods. Otis protested these searches, declaring that “A man’s home is his castle.” The principle is a strong one. While the monarch rules in the realm, the head of household should rule in his own home, where government should not be able to intrude at will.

The last document in the collection is George Washington’s address resigning his commission as commander in chief of the Continental Army in December 1783.

What other considerations governed your choice of documents?

I aimed at geographic diversity. Although Boston was a hotbed of the Revolution prior to independence, not everything happened there. And along with the voices of the famous, I wanted to include those of the ordinary citizen: for example, the memoir of Hugh McDonald, a soldier from North Carolina, and a newspaper account of a “petticoat army” formed by the women of Stratford, Connecticut, in March of 1776, to protest a local family’s decision to name their newborn after Thomas Gage, the British general who had been in charge in Boston.

Also, I looked for documents that had not been widely published before. One is a list of British war crimes to appear in an illustrated children’s book. Such a children’s book could never be published today! But the Continental Congress wanted to use it to stoke Patriot sentiment. They assigned the project to Benjamin Franklin, then ambassador to Paris. Lafayette, visiting France on temporary leave from his service in the Revolution, helped compile the list. The book was never made—they never found an illustrator. But the document demonstrates that in the matter of independence, time was on the Patriots’ side. The longer the war dragged on, the more the British army alienated the American population.

Was the American Revolution inevitable? Could the Patriots’ disagreement with Great Britain have been worked out in another way?

I really think the Americans tried as hard as they could to find a solution, some way to get the British to respect their rights without going to war or declaring independence. Prior to the 1760s, Americans were happy to be English, citizens of the freest nation on the planet. As Englishmen in America they were even more free and more prosperous.

Many read Locke’s Two Treatises on Government, which explained why England’s 1688 “Glorious Revolution,” which deposed James II and put William and Mary on the throne, was legitimate. Government’s purpose was to protect people’s rights to life, liberty and property. When government did not respect these rights, the people had a right to petition and protest. If government persisted in disregarding these rights, then the people had a right to revolution.

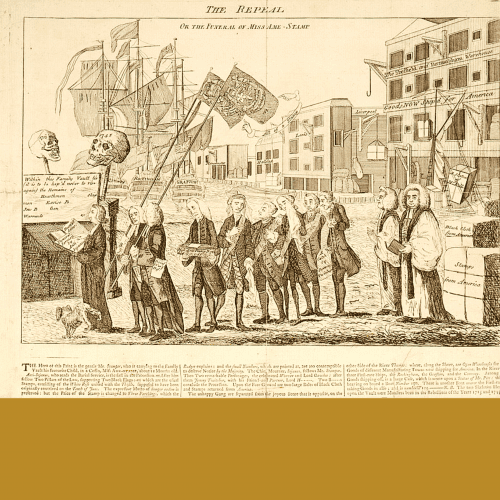

Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-21264.

There were attempts at compromise and some concessions on the part of the British. Due to American resistance, the British collected none of the revenue they’d expected from the Stamp Act, so they repealed it in 1766. But they simultaneously passed the Declaratory Act, which said that they had the right to govern us in all cases whatsoever. The Townsend Duties of 1767 imposed taxes on lead, glass, paint, paper and tea. All of those taxes, except for the one on tea, were repealed in 1770. Still, tensions escalated. In December of 1773 the Boston Tea Party occurred. The British government then in power was in no mood to compromise. They thought the previous strategy of concessions had failed. Hence in 1774 they passed the Coercive Acts (which Americans called the Intolerable Acts). They shut down the Boston Harbor, made it illegal for the Massachusetts legislature to meet, and even made it illegal for town meetings to take place in Massachusetts without British permission.

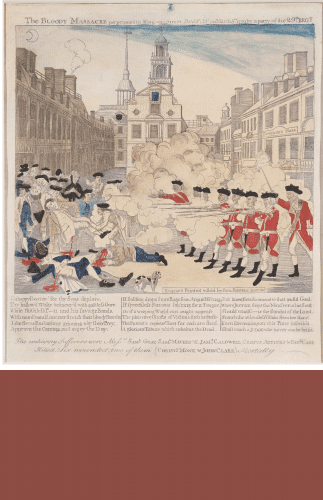

The British had violated Americans’ rights to liberty and property. Then the 1770 Boston Massacre took American lives; and in 1775, the British attempt to seize the colonists’ weapons and ammunition at Concord began the bloodshed of the war. If at first the leaders of the resistance movement—people like Sam Adams and James Otis—had been regarded as conspiracy theorists, by 1775 they seemed like prophets.

The first big public call for independence came from Thomas Paine, who published Common Sense in January 1776. Yet many Americans hesitated. The test vote for independence taken on July 1, 1776 in the Continental Congress—a full year after the Battles of Lexington and Concord—was not unanimous. South Carolina, Delaware, Pennsylvania and New York did not vote with the majority. One day later, the vote changed. Delaware’s Caesar Rodney rode his horse through the night to swing his delegation to the affirmative side on July 2. John Dickinson of Pennsylvania opposed independence, yet stood aside and allowed his colleagues to support it. South Carolina delegates reversed their vote, while New York delegates, awaiting instructions from their legislature, abstained. But it had been a tough sell.

Prior to this time, had a colonial people ever succeeded in throwing off the rule of the colonizer? Why did the American revolutionaries think they could succeed?

Nothing comparable comes to mind. The Americans were not sure they could pull it off. In his last letter, Jefferson recalls this time as requiring “a doubtful election between submission and the sword.” In 1776, we hardly won any battles. Washington was routed on Long Island and in New York City and finally saved the day by crossing the Delaware at Trenton. Things could have gone down differently. But the Patriots believed that their cause was just. You remember the old story of Franklin quipping to the signers of the parchment copy of the Declaration, “We must all hang together, or surely we will all hang separately.”

Was Washington’s leadership critical to the success of the Revolution?

I think it absolutely was. James Flexner titles his biography of Washington, The Indispensable Man. It’s difficult to imagine any other commander as selfless, as respectful of the civilian authority of the Continental Congress, and as determined to step down from his position when the war was over. Artist Benjamin West was painting the portrait of George III when the king asked him what George Washington would do if the Americans won the war. West replied that Washington planned to return to his Mount Vernon estate. The king couldn’t believe it—wouldn’t Washington become America’s new monarch? He said that if Washington relinquished power and went back to private life, then truly he would be the world’s greatest man. And that’s exactly what Washington did.

When the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783, was the American Revolution complete?

The Revolution was about more than independence.

Americans still needed to consolidate the lessons they had learned about self-government. The new state governments we created for ourselves when we declared independence very much reflected the spirit of ’76. Due to the bad memories of royal governors, they provided for very weak executives. The Confederation government also had fairly limited powers, because citizens did not want to be beholden to a distant capitol. Because the Continental Congress lacked the power to tax, they could pay for war costs either by asking for contributions from the states—who themselves lacked much power to tax—or by printing money, causing hyper-inflation. One lesson learned was that, although government could be so powerful as to pose a threat to liberty, it could also be too weak to defend liberty.

The Army experienced firsthand the shortcomings of the Articles of Confederation. Soldiers went without pay and were poorly provisioned and supplied. It’s no surprise that among the nationalists pushing for a new constitution in 1787 were many former Continental Army officers.

Moreover, Americans still needed to realize the full meaning of the principles they asserted in 1776. Members of the Revolutionary generation were the first to realize that slavery was inconsistent with their principles. Beginning during the war and continuing afterward, some states abolished slavery or embraced gradual emancipation laws. They also began to disestablish churches. With Abigail Adams’s letter to her husband John in 1776, you see the beginning of a movement for women’s rights. Abigail uses the logic and rhetoric of the Revolution to make the case that “all men would be tyrants if they could,” and that women have rights that should be respected.