The First National Anti-Slavery Organization

The American Anti-Slavery society was founded in Philadelphia 180 years ago, in December of 1833. The group agreed to a simple “constitution,” prefaced by a brief but eloquent “manifesto” that quoted both the Biblical commandment to love one’s neighbor as oneself and the central idea of the Declaration of Independence, that “all men are created equal.” Arthur Tappan became the society’s first president, while William Lloyd Garrison, who had already founded his abolitionist weekly The Liberator, was asked to write a “Declaration of Sentiments” expressing the organization’s aims.

Although the American Anti-Slavery Society was the first national organization of its kind, similar state organizations had already formed. Most of the earliest of these were organized by the Society of Friends, or Quakers. The very first one, The Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, had formed in 1774 and helped to pass Pennsylvania’s Gradual Abolition Act of 1780, the first anti-slavery legislation in the United States.

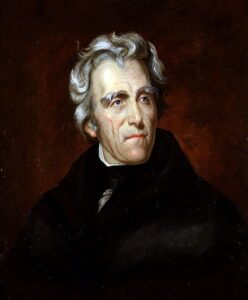

Benjamin Franklin, assuming presidency of this organization in 1787, had led the group in petitioning Congress to abolish slavery in 1790, an effort denounced by southern congressmen and doomed to failure due to fear it would rend the still-untested unity of the new federal republic.

By the 1830s, abolitionist sentiment was growing in many of the northern states, partly under the influence of an evangelical religious revival, the “Second Great Awakening.” Revivalist Congregationalists such as Charles Finney and Theodore Weld did much to promote the abolitionist movement. Free Black ministers such as Samuel Eli Cornish were among those founding the Anti-Slavery Society.

Beginning with 60 members, the Anti-Slavery Society would grow to a membership of 250,000 by 1840, with 2000 local chapters. But by then it would also begin to splinter into separate organizations, due to disagreements over how forcefully to press for nation-wide abolition, whether to press for it within the existing political and Constitutional system, whether established religious denominations offered the best medium for spreading the message, and whether to allow women active roles in the movement. Garrison, pushing a radical agenda, gained leadership of the AASS while Tappan and others formed separate groups. Nevertheless, disagreements over approach did not halt the growth of the abolitionist movement as a whole.

Other abolitionist writings and related teaching resources are available in an NEH lesson plan developed by TAH, Slavery’s Opponents and Defenders.