The Spanish-American War: The Beginning of the American Century?

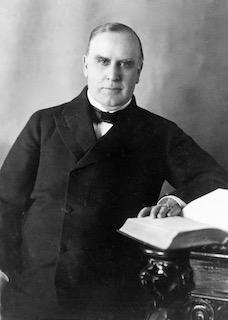

The 1896 presidential contest pitting Democratic candidate William Jennings Bryan against the Republican nominee William McKinley centered on economic issues. Bryan, nominated on the strength of his electrifying Cross of Gold speech at the Democratic Convention, called for the free coinage of silver and the elimination of the protective tariffs favored by the Republican party. The Republicans supported maintaining protectionism and the gold standard. Buried beneath each party’s platform statements on tariffs and monetary policy were similar positions on a foreign policy issue, Cuba. In 1895, Cuban insurgents launched an effort to seize control of the island from Spain and establish an independent Cuba. In their 1896 campaign platforms, both parties expressed support for the rebel’s “heroic” struggle.

William McKinley won the presidency in 1896. He had hoped to focus on domestic issues as President, but the Cuban revolt demanded much of his attention. President McKinley offered to mediate between Cuba and Spain in 1897 but was rebuffed by both sides. Spain hoped to stave off its international decline, while the Cuban rebels worried that a ceasefire followed by extended negotiations would drag on and on. They wondered if their rebel army would disband if inactive for too long.

Meanwhile, American public sentiment for war grew, aided, and abetted by the era’s “Yellow Journalism.” The two largest newspaper organizations in the country, owned by William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, engaged in a bitter circulation contest. They competed for sales with lurid stories and sensationalized headlines. When Hearst sent artist Frederic Remington to Cuba to supply drawings of Spanish brutality and oppression, Remington politely told his employer, “There is no war here.” Hearst allegedly replied, “You furnish the pictures, and I will furnish the war.”

Spain provided Hearst plenty of ammunition. Spain ordered Cubans to resettle in camps known as reconcentrados to control the Cuban countryside. The camps suffered from poor food, disease, and unsanitary conditions. Countless Cubans starved to death in the camps. The reconcentrado program horrified Americans. Yellow journalists painted the Cubans as heroic figures who only wanted their freedom. Instead, they claimed, the Spanish butchers were starving the Cuban people.

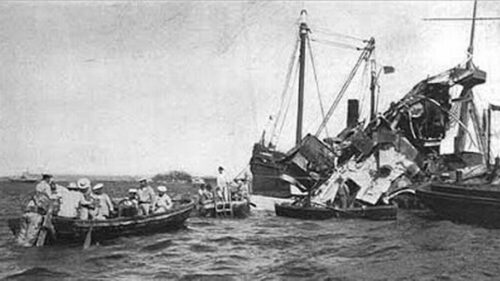

Then two events not in his control helped push McKinley toward war. On February 9, 1898, Hearst’s New York Journal published a letter written by Spain’s ambassador to the United States, Enrique de Lome, accusing McKinley of being a “weak” crowd pleaser. The insult enraged the American public. Just six days later, a U.S. warship, the USS Maine, in the harbor at Havana, Cuba’s capital, exploded and sank. The disaster cost the lives of 268 American sailors, more than two-thirds of the Maine‘s crew. Sensational headlines blamed Spain, accusing her of a military attack on a U.S. ship. A naval investigation concluded that an external explosion likely sank the ship, but the report did not blame Spain. Most naval historians now believe the explosion was internal – caused by a fire in a coal storage unit. (For more information on the debate, read the U.S. Naval Institute’s Report on the Sinking of the Maine, 1989).

On March 26, 1898, McKinley sent Spain an ultimatum, although he avoided that specific word. McKinley wanted an armistice until October 1, followed by negotiations and a revocation of the reconcentrado program. If no agreement were reached by October 1, Spain and Cuba would submit to arbitration. When Spain failed to respond to McKinley’s ultimatum in a manner acceptable to him, he sent a message to Congress asking for authorization to intervene in Cuba militarily, a step everyone knew would inevitably lead to war.

What compelled McKinley to take this step?

The simple answer is usually the best, but not in the case of the Spanish-American War. The simple answer is that Spain blew up the Maine, the United States invaded Cuba for revenge, and trounced Spain in what Secretary of State John Hay called “a splendid little war.” Most historians would not deny that the sinking of the Maine played a role, but few would call it determinative. They have some evidence to back them up. In his message to Congress, President McKinley cited four justifications for U.S. intervention in Cuba – none mentioning the Maine.

First, McKinley said, “the cause of humanity” justified U.S. intervention to end the barbarous Spanish reign. Next, he argued that intervention was necessary to protect the lives and property of American citizens in Cuba. Third, McKinley claimed that Spanish control of Cuba threatened American business interests in the region. Finally, he argued that the threat was ongoing, citing the Maine explosion as evidence that Spain could not provide the order and stability necessary to end the threat to American citizens, property, and commercial interests. Still, he did notcite the explosion as a specific justification for U.S. intervention.

Historians have cited multiple reasons for McKinley’s decision to intervene in Cuba. Each scholar emphasizes one or two reasons over the others. Some cite partisan congressional politics as the driving factor. Congressional Republicans were concerned that Democrats could use the situation in Cuba to their advantage in the 1898 congressional elections, so they pressured McKinley to be more forceful. Others argued that commercial and business interests were the primary reason for McKinley’s position. Some Americans believed the Panic of 1893 began because of an excess supply of manufacturing products. They saw expansion in the Caribbean and Pacific Oceans as a way to address the glut. Historian Nick Kapur argues that closely held personal values drove McKinley’s thinking, such as his belief in arbitration, his Methodist faith, and his aversion to war because of the horrors he witnessed in the Civil War.

The historian’s debate is a learning opportunity for high school students. The primary sources on TAH’s website and other sites raise questions that allow students to practice history as professionals do. Students can examine the domestic context that preceded the war, the reasons for McKinley’s call to arms, and reach conclusions about why they think he opted for war.

Or teachers might choose to concentrate on the consequences of the war. The American-Filipino War fueled an intense debate over American imperialism. Students should consider the balance between America’s economic and strategic interests and its faith in the principles of natural rights and consent of the governed. If you’re interested in helping your students sort through those issues, we recommend you examine our Core Document Collection Document and Debates Volume Two, where you will find a debate on American involvement in the Philippines during the Progressive Era.

Ray Tyler was the 2014 James Madison Fellow for South Carolina and a 2016 graduate of Ashland University’s Masters in American History and Government. Ray is a former Teacher Program Manager for TAH and a frequent contributor to our blog.