Introduction to the Constitutional Convention

Wanted: State Governments

On May 15, 1776, the Second Continental Congress, meeting in Independence Hall in Philadelphia, issued “A Resolve” to the thirteen colonies:

“Adopt such a government as shall, in the opinion of the representatives of the people, best conduce to the safety and happiness of their constituents in particular and America in general.”

Between 1776 and 1780, each of the thirteen colonies adopted a republican form of government. What emerged was the most extensive documentation of the powers of government and the rights of the people that the world had ever witnessed.

Uniform Systems of State Government

These state constitutions displayed a remarkable uniformity. Seven attached a prefatory Declaration of Rights, and all contained the same civil and criminal rights. Four states decided not to “prefix” a Bill of Rights to their constitutions, but, instead, incorporated the very same natural and traditional rights found in the prefatory declarations. New York incorporated the entire Declaration of Independence into its constitution.

The primary purpose of these declarations and bills was to outline the objectives of government: to secure the right to life, liberty, property, and the pursuit of happiness. The government that was chosen to secure these rights was declared universally to be “a republican form of government.” All of the states, except Pennsylvania, embraced a two-chamber legislature, and all, except Massachusetts, installed a weak executive and denied the Governor the power to veto bills of the legislature. All accepted the notion that the legislative branch should be preeminent, but, at the very same time, endorsed the concept that the liberty of the people was in danger from the corruption of the representatives. And this despite the fact that the representatives were installed by the election of the people. Thus, each state constitution embraced the notion of short terms of office for elected representatives along with recall, rotation, and term limits.

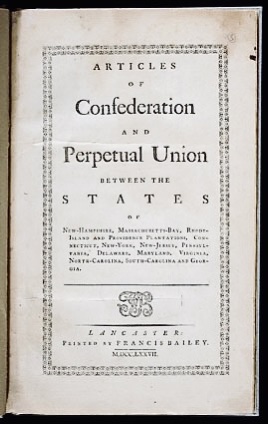

Creating the Articles of Confederation

The Second Continental Congress also created the first continental-wide system of governance. The Articles of Confederation created a nation of pre-existing states rather than a government over individuals. Thus, the very idea of a Bill of Rights was irrelevant, because the Articles did not give the Confederation government power over individuals. The states were equally represented in the union regardless of the size of each state’s population; only one branch was needed; normal political activity required the support of super majorities; the union was limited to the powers expressly enumerated; and amendment was required to endow the union with powers that weren’t specifically articulated. Amendments required the unanimous approval of all thirteen state legislatures. All of the states were required to “sign on” before the Articles became operative on any one state. Because of territorial disputes between two states, the Articles didn’t come into operation until the early 1780s.

Healthy State Governments and a Weak Continental System

Hence, two opposite and rival situations arose: an early operating, robust and healthy state and local politics, and a late arriving, weak and divisive continental arrangement. Several statesmen, especially George Washington, were concerned that the idea of an “American mind” that had emerged during the war with Britain was about to disappear, and the Articles of Confederation were inadequate to foster the development of an American character. According to Washington, “we have errors to correct.” He argued that the states refused to comply with the articles of peace; the union was unable to regulate interstate commerce; and that when the states met in Congress, they did so grudgingly, only complying with the minimum interstate standards required by the Articles. Others, especially James Madison, were concerned that the state legislatures—dominated by what he saw as oppressive, unjust, and overbearing majorities—were passing laws detrimental to the rights of individual conscience and the right to private property. And there was nothing that the union government could do about it, because the Articles left matters of religion and commerce to the states. The solution, concluded Madison, was to create an extended republic, in which a variety of opinions, passions, and interests would check and balance each other, supported by a governmental framework that endorsed a separation of powers between the branches of the general government.

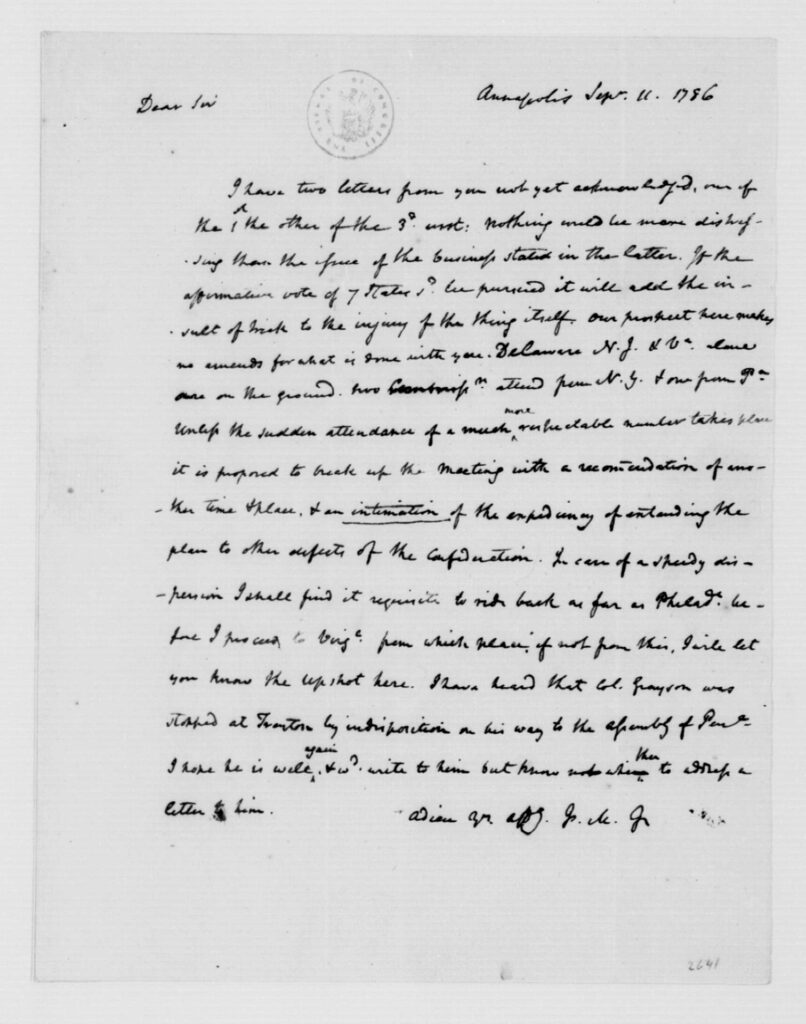

Virginia Calls for the Annapolis Convention

Between 1781 and 1785, attempts “to correct these errors” failed to secure the required unanimous consent of the state legislatures. Matters changed, however, in 1786. Following James Madison’s suggestion of 21 January 1786, the Virginia Legislature invited all the States to convene in Annapolis, Maryland to discuss ways to reduce interstate conflicts. The “commissioners” in attendance at Annapolis during September 1786 chatted about these particular concerns, but suggested that the conversation be both deepened and widened. They endorsed a motion that a “Grand Convention” of all the States meet in Philadelphia in May 1787 to discuss how to improve the Articles of Confederation.

One might well ask, “Who or what authorized the Virginia Legislature to call the Annapolis Convention, and who or what authorized the Annapolis Convention to call for a ‘Grand Convention’?” The answer is to be found in the Declaration of Independence: The people have the right to choose the form of government under which they shall live and to install such government as they deem appropriate to secure their liberty, security, and happiness.

The Initial Delegates

Madison and Washington agreed that the principles of the Revolution of 1776 were in danger due to a weak continental arrangement and overbearing, unjust, and reckless state legislatures. But how could they take advantage of the opportunity provided by the recommendation of the Annapolis Convention? How was such a bold proposal to be put into effect?

Madison persuaded the Virginia Legislature to implement the challenge of the Annapolis Convention and invite all the other states to also reconsider the status of the Articles. He also persuaded the Assembly to be the first to elect delegates to the Grand Convention to consider the business “of May next.”

Virginia’s Delegates

The Virginia Assembly elected 55-year-old revolutionary hero George Washington to head the delegation. “Give me Liberty or give me Death” Patrick Henry declined, because “he smelt a rat.” Doctor James McClurg was selected, even though he had no political experience, because James Madison insisted he be present. Richard Henry Lee and Thomas Nelson, colonial heroes and Signers of the Declaration, refused to attend. Others chose were 34-year-old Edmund Randolph, the Governor of Virginia; 55-year-old John Blair, an esteemed Virginia judge; 55-year-old George Wythe, the first law professor of the United States and a Signer of the Declaration; and 62-year-old George Mason, author of the Virginia Bill of Rights, along with five-foot-tall, 120-pound, 36-year-old James Madison.

Five States followed Virginia’s lead

New Jersey

. . . selected William Churchill Houston; Chief Justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court David Brearly; 40-year-old Irish immigrant William Paterson; Governor William Livingston, known as “the Whipping Post” because of his great height; and 27-year-old Jonathan Dayton, who after the Convention went exploring and died in what is now Dayton, Ohio.

Pennsylvania

. . . selected eight delegates. Thomas Mifflin, speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly, was elected as the leader of the delegation. Other members selected were Robert Morris, financier of the Revolution; George Clymer, signer of the Declaration; Jared Ingersoll, a political reformer who later bestowed on Madison the appellation, “Father of the Constitution;” Irish immigrant Thomas Fitzsimons, founder of the Bank of America and one of two Catholics at the Convention; 45-year-old James “The Caledonian” Wilson from Scotland; 33-year-old peg-leg and “rake” Gouverneur Morris, who spoke more than anyone at the Convention; and 81-year-old Benjamin “the American Socrates” Franklin, who was added to the delegation as a courtesy. All the delegates from Pennsylvania resided in Philadelphia.

North Carolina

Former Governor Alexander Martin was chosen to lead the North Carolina delegation, but left before the signing. William Davie, 29 yers old, also left the Convention early. In 1802 he was killed in a duel. Richard Dobbs Spaight, 29 years old; preacher, essayist, and mathematician Doctor Hugh Williamson; and land speculator William Blount—who later earned the dubious honor of being the first member expelled from the United States Senate—made up the core of a delegation that had a major impact on the course of the debates in July. Howard Christy gives this delegation central signing honors in his commemoration of the Constitution.

Delaware

. . . chose 54-year-old George Read to head its delegation. Additional members included “corpulent and impetuous” Gunning Bedford Junior, prudent and educated John Dickinson, and two quiet 35-year olds: Jacob Broom and Richard Bassett.

Georgia

The head of the Georgia delegation was William Few. He was joined by Abraham Baldwin, William Houstoun, and 49-year-old William Pierce, one of the poorest attendees in terms of income—thus he has no official portrait. Pierce did, however, compose a series of “Character Sketches” that give us insight into the characters of his fellow delegates.

The Endorsement of the Confederation Congress

So six of the states, led by Virginia, began to form a Grand Convention without waiting for any formal endorsement by the existing government under the Articles of Confederation. Other states, however, were more cautious and wanted the existing Congress to address the legitimacy of such a gathering. On 28 February 1787, the Confederation Congress endorsed the meeting of the Grand Convention on “the second Monday in May next.” Exactly what the Congress authorized became a bone of contention. In its act to recommend the convention, Congress said a Convention of delegates should meet

“for the sole purpose of revising the articles of Confederation and reporting to Congress and the several legislatures such alterations and provisions therein as shall, when agreed to in Congress and confirmed by the States, render the federal Constitution adequate to the exigencies of government and the preservation of the Union.“

(Italics are in the original of the version reprinted in Federalist 40.)

Did the Congress limit the Convention to the discussion of specific and particular matters? Or did the Congress empower the Convention to “run away” and propose whatever alterations the delegates considered were needed to preserve the principles of the Revolution?

New York’s Delegates

New York was the first state to act after the Congressional endorsement. The faction of the New York legislature allied with Governor George Clinton selected State Supreme Court Judge Robert Yates and John Lansing to, in effect, outvote Alexander Hamilton. The New York delegation was not particularly prominent at the Convention. Yates and Lansing left in early July, just prior to the passage of the Connecticut Compromise, and the 32-year-old Hamilton, who lost his life at age 49 in a duel with Aaron Burr, was far more influential in securing the adoption of the Constitution in 1788 than in its framing in 1787.

Five States followed New York’s lead

South Carolina

In early March, South Carolina acted, appointing John Rutledge, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, Charles Pinckney, and Pierce Butler as their delegates. They were pro-national, pro-slavery, and very influential.

Massachusetts

Massachusetts, also in March, selected Elbridge Gerry, who signed the Declaration; 32-year-old Rufus King; “backwoods lawyer” Caleb Strong; and Nathaniel Gorham, who chaired the Committee of the Whole during the Convention.

Connecticut

Four days before the Convention began, Connecticut elected three delegates: William Samuel Johnson, who learned of his appointment to the Presidency of Columbia College while on his way to Philadelphia; Roger Sherman, who signed both the Declaration and the Articles; and 42-year-old Oliver Ellsworth, who had the reputation of talking to himself and being a chain chewer of snuff.

Maryland

Irish immigrant Doctor James McHenry, after whom Fort McHenry is named, was a leader of the Maryland delegation. He was joined by 60-year-old bachelor, Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer; 30-year-old Daniel Carroll—one of two Catholics at the Convention; 29-year-old John F. Mercer, who blew into and out of town during the first week of August; and Luther Martin, who apparently had a great capacity to consume immense amounts of alcohol and sober up at a moment’s notice.

New Hampshire

New Hampshire was short of cash, so John Langdon funded the expenses for himself and Nicholas Gilman. They arrived at the Convention on July 23, after the main debate over the Connecticut Compromise was completed and yet just in time for a one-week recess.

Rhode Island, the thirteenth state, declined to send delegates.

The Delegates as “Demi-Gods”

Thomas Jefferson characterized the 55 men who showed up in Philadelphia as “demi-gods” who created a Constitution that would last into remote futurity. Alexis de Tocqueville marveled at the work of the American Founders: never before in the history of the world had the leaders of a country declared the existing government to be bankrupt, and the people, after debate, calmly elected delegates who proposed a solution, which, in turn, was debated up and down the country for nearly a year, without a drop of blood being spilled. Madison, in Federalist 37, indicates the uniqueness of the Founding. Never before had there been a democratic founding; all previous foundings had been the work of a single founder like Romulus. And Hamilton, in Federalist 1, suggested that this was a unique event in the history of the world. Finally, government was going to be established by reflection and choice rather than force and fraud. And what is also unique is the fact that the framers were relatively young, well educated, and politically experienced. Like the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution was written by delegates immersed in 1) the writings of Aristotle, Cicero, Locke, and Montesquieu, and 2) a world of political experience at both the state and continental level. Both basic documents were written in Independence Hall, Philadelphia, and thirty signers of the Declaration in 1776 played a vital part in the creation and adoption of the Constitution, 1787-1789.

How to Read the Convention

During most of the four months the Convention met, the delegates were never certain they could reach the compromises necessary to complete their task. We believe the Convention is best understood as a four-act drama in which conflicts arise, hopes for solution rise and fall, and those most committed to framing a new government work hard to arrive at solutions. Elsewhere in this exhibit, we present the drama in full; below, we offer a summary.

The First Delegates Arrive

Very few of the delegates selected were present at the appointed time for the meeting of the Grand Convention in Philadelphia on May 14, 1787. All the Virginia delegates were present, however, and fully settled into their accommodations. Washington stayed at Robert Morris’s Town House, and Madison secured lodgings across the street at Mrs. House’s Boarding House. During this waiting period, the Virginia delegates caucused with each other in an attempt to set the tone for the deliberations of the Convention and paid courtesy calls on prominent members of Philadelphia society. Some entered a Catholic church for the first time.

Setting the Ground Rules

On May 25, a quorum of seven states was secured. The first order of business was to elect a President, and George Washington was the obvious choice. William Jackson, yet another immigrant at the Convention, was elected Secretary of the Convention, and he recorded the propositions and amendments as well as the vote tabulation. James Madison took extensive Notes of the proceedings, and although some scholars have questioned their authenticity and completeness, they remain the primary source for reproducing the conversations at the Convention. Other delegates kept specific notes on certain days; there are letters back home to friends and loved ones; there are urgent bills sent for immediate payment that augment; and there are personal diaries, some more complete than others. Nothing, however, can compete with, or ever replace, Madison’s Notes.

The delegates also agreed that the deliberations would be kept secret. The case in favor of secrecy was that the issues at hand were so important that honest discourse needed to be encouraged, and delegates ought to feel free to speak their mind, and change their mind, as they saw fit. Thus, despite the hot summer weather in Philadelphia, and delegates who, on the whole, were rather overweight and hardly “dressed down” for the occasion, the windows were closed and heavy drapes drawn. The merits and demerits of the secrecy rule have been a subject of considerable debate throughout American history.

Act I of the Convention

In Act I of the Convention, Governor Randolph introduces the fifteen-point Virginia Plan at the end of May to “revise the Articles of Confederation.” The decisive features of this plan are 1) the complete structural exclusion of the states in terms of both election and representation; 2) the complete diminution of the powers of the states and the virtual freedom of Congress to act in those areas for which the states are incompetent; 3) the establishment of an extended national republic with institutional separation of powers and the introduction of the possibility that short terms of office and term limits—standard features of traditional republicanism—will be abandoned. Under the wholly federal Articles of Confederation, only the states are represented and the central government is restrained to the exercise of expressly delegated powers. And under the state republican constitutions, the governor has very little authority, and the elected representatives are kept under close scrutiny. Madison’s Virginia Plan introduces a new understanding of federalism and republicanism. This wholly national republican plan is debated, and amended, over the next two weeks, and the main features are adopted by the delegates in mid-June, in preference to two alternatives: the wholly federal, or state-based, New Jersey Plan, that argues that the Virginia Plan goes too far, and the Hamilton Plan that claims the Virginia Plan does not go far enough. Hamilton, among other things, envisioned a President for life.

Act II of the Convention

Act II portrays the Convention in crisis, in the sense that the delegates are at a stalemate. Far from accepting the wholly national republican Virginia Plan, as we might very well anticipate when the curtain falls at the end of Act One, the delegates from Connecticut, New Jersey, Delaware, New York, along with Mr. Martin from Maryland—the defenders of the New Jersey Plan, the old style federalism of the Articles, and the old fashioned republicanism of the state constitutions—now insist on questioning the validity of the Virginia Plan. They argue that the Convention has exceeded the Congressional mandate because the Articles have in fact been scrapped rather than revised. Thus the Convention has violated the rule of law. Moreover, the Convention is about to propose a novelty—a large country under one republican form of government—that will never be accepted by the electorate. These delegates, knowing their Locke and Montesquieu and relying on their own political experience, which is remarkably extensive, think republican government can only exist in areas of small extent where the people keep close watch over their representatives.

A breakthrough occurs at the end of June when Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut suggests that we are neither wholly national nor wholly federal but a mixture of both. Several delegates echo this theme and the Convention decides to move beyond the exclusively national or federal paradigms. The Gerry Committee is created to explore the ramifications of the suggestion that the people be represented in the House and the states be represented in the Senate. This recommendation—the Connecticut Compromise—is accepted over Madison’s objections in mid-July.

Act III of the Convention

Act III focuses on the debates during August over the Committee of Detail Report, especially concerning the itemization of Congressional powers. With the Connecticut Compromise in place, the delegates turn from the question of structure to the question of national and state powers. Under the Virginia Plan, Congress was empowered to do anything the States were incompetent to do. By July, that is no longer acceptable to the delegates. A Committee—the Committee of Detail—is created to draft a Constitution that will address the division of powers between the central and state governments and also the separation of powers between Congress, the President, and the Supreme Court.

Another issue that emerges in Act Three is the slavery question. What can Congress do and not do to regulate and/or abolish slavery? This is a vital question and deserves special coverage. It is instructive to compare the clause in the Committee of Detail Report of August 6 with the Signed Constitution of September 17. The former forbids Congress from ever regulating the slave trade and prohibits Congress from discouraging the trade by means of a tax or tariff. By contrast, the final Constitution specifies that the prohibition on Congress will expire in 1808 and permits Congress to discourage the slave trade. In keeping with these revisions, in March, 1807, President Jefferson will sign into law an Act of Congress prohibiting the slave trade effective January 1, 1808, and during the 1790s Congress will take specific steps to discourage the importation of Africans for the purpose of being sold into slavery.

Act IV of the Convention

Act IV covers the final three weeks of the Convention during the month of September. Despite all the progress that has been made on the structural role of the states and enumerating the powers of Congress, there is much work still to be done on the Presidency. The Brearley Committee comes up with the idea of an Electoral College as a sensible compromise to the long and largely fruitless debates on how to elect the President. It has been clear for four months that until the mode of election was settled, no progress can be made on 1) length of term, 2) the issue of re-eligibility, and 3) the powers of the President. The Electoral College is modeled on the Connecticut Compromise: the President will be elected by a combination of people and states.

The Committee of Style writes the final draft of the Constitution. It includes a Preamble and an obligation of contracts clause, both written by Gouverneur Morris, and an enumeration of the powers of Congress in Article I, Section 8. During the last week of the Convention the delegates add a few refinements, raise some serious concerns, and discuss what they agreed to over the four months of deliberations. Mason expresses the wish that “the plan had been prefaced by a Bill of Rights.” Elbridge Gerry supports Mason’s unsuccessful attempt to attach a Bill of Rights. Randolph joins Mason and Gerry, declaring that he too won’t sign the Constitution. And the delegates wonder whether or not the power to create a national university is implied within the meaning of the necessary and proper clause.

On the last day of the Convention, September 17, Benjamin Franklin looks at the chair occupied by Washington and the sun enshrined on its back. Over the four months of deliberation, frustrated delegates often worried that it was a setting sun. Franklin now assures the delegates that it is a rising sun.