Documents and Debates: The Nullification Crisis

High above the football stadium at Clemson University sits Fort Hill, the stately antebellum home of John C. Calhoun. On game days at Clemson, the marching band parades down the hill in front of Calhoun’s house on its way to Memorial Stadium, nicknamed “Death Valley” by the Clemson faithful. Countless fans follow the band to the stadium clapping time to Tiger Rag, the school’s fight song.

Fort Hill is designated as a national historic site and is open to visitors. According to campus legend, students who tour the home as undergrads are destined to never graduate. As an American history teacher, I wanted to tour the Calhoun home on my first visit to the campus when I helped my son Ben move into his freshman dorm. I delayed doing so until I attended his graduation in 2013. Ben insisted that we not take the risk.

There is a lot of history at Fort Hill. In a small office in the back of the home, John C. Calhoun wrote his well-known essays on nullification, the political theory that individual states had the right to declare federal legislation unconstitutional. The home’s large dining room is furnished with a handsome mahogany sideboard, commissioned as a gift to Calhoun from fellow senator Henry Clay of Kentucky and constructed of wood taken from “Old Ironsides,” the USS Constitution, during a refurbishing.

Thomas Green Clemson, for whom Clemson University is named, married Calhoun’s daughter Anna Marie in 1838. Clemson inherited the estate when Anna died and bequeathed the Fort Hill home, 841 acres of land surrounding the house, and $80,000 to the state of South Carolina on the condition they establish a mechanical and agricultural college on the site—an agreement South Carolina fulfilled in 1889. In the words of historian Edward L. Ayers, the founding of Clemson Agricultural College in 1889 “was driven both by the national government’s support for land-grant colleges and by the practical bent of Southern legislators and benefactors.” This push for expanding educational opportunities in the South fit the “New South” philosophy prominent among white southerners after Reconstruction. New South proponents accepted that slavery was dead and called for the diversification of the southern economy. Yet they insisted on maintaining an odious racial hierarchy barely distinguishable from that of the Old South of John C. Calhoun.

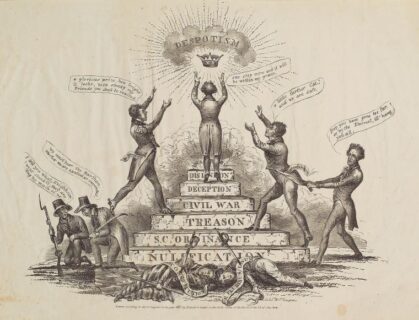

Unlike Thomas Clemson, Calhoun is not known for founding a university. Instead, Calhoun gave voice to the attitudes that led to the Civil War—and, as a consequence of that war, the ruin of the Old South economy. In addition to his political treatises on the doctrine of nullification, Calhoun’s legacy includes his infamous “Slavery a positive good” speech. In that speech, Calhoun defended the South’s “peculiar institution” against abolitionist petitions flooding Congress in the 1830s. Though the nullification crisis evolved as a protest against the Tariff of 1828, slavery was a powerful undercurrent in that debate. If South Carolina could persuade other slave states that they had the power to declare federal legislation unconstitutional, slavery’s defenders would possess a potent weapon against abolitionism.

The Nullification Crisis can be especially challenging for teachers of American history and government. The doctrine rests upon the theory that the United States was formed as a compact among the states and not by the consent of American people as a whole. Students may also find tariffs confusing and lack the context necessary to understand why tariffs were so controversial in Antebellum America. And since students are typically taught that the Supreme Court settled the issue of judicial review—the power to declare federal legislation unconstitutional—in the case of Marbury v. Madison, they may find the conflict over nullification a confusing throwback to an earlier controversy. Given the topic’s complexity, it is not surprising to hear social studies coordinators report that their students struggle with nullification questions on state-mandated assessments.

The documents in our Core Document Collection, Chapter 11: The Nullification Crisis, from Volume I of Documents and Debates in American History, help students see the complexity of the debate between slaveholding planters in the South and merchants and manufacturers in the free-soil North. The Southern ruling class supported lower tariffs because they purchased a large volume of goods from Europe. Northern manufacturing economic interests demanded a high protective tariff for their infant industries. Yet, the debate went well beyond regional economic interests. Defenders of nullification argued that it was a justifiable constitutional remedy protecting state sovereignty when the national government exceeded its delegated powers. Southerners wanted the remedy to protect them against both higher tariffs and abolitionism. Opponents saw it as an assault on the Union and a subterfuge for a defense of slavery.

At Teaching American History, we believe students best understand history when they are encouraged to dive into the primary sources, closely reading the words written by the authors of the time and putting their questions to those authors themselves. In this way, students reach their own conclusions about the choices made by Americans of the past. We encourage you to engage your students in a close reading of these documents, as they discuss who should have the final say on the constitutionality of legislation in a federal system.

Documents in this chapter include:

- Excerpts from Ratification Documents of Virginia and New York

- John C. Calhoun, Rough Draft of What is Called the South Carolina Exposition, December 19, 1828

- Senator Robert Y. Hayne, Remarks in Congress, January 25 and 27, 1830

- James Madison, On the Nullifying Doctrine, April 3, 1830

- Lyrics to Jackson and the Nullifiers, 1832

- Epitaph for the Constitution, 1832

Additional Documents connected to the Nullification Crisis:

- Virginia Resolution of 1798

- Draft of the Kentucky Resolution, 1788

- Fort Hill Address, John C Calhoun, July 26, 1831

We have also provided audio recordings of the chapter’s Introduction, Documents, and Study Questions. These recordings support literacy development for struggling readers and the comprehension of challenging text for all students.