Tyler Nice: Teaching with Lincoln

Each year, one outstanding social studies teacher from each state is named Teacher of the Year by the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Teaching American History can point to many of our teacher partners among past awardees. This year, we’re proud to announce that two recent MAHG graduates were honored: Tyler Nice (graduated 2021) won for Oregon; and Lucas George (graduated 2022) won for Ohio. In this post, we tell Nice’s story. We’ll share George’s story in a later post.

Oregon Teacher of the Year: Tyler Nice

Entering his twentieth year as a social studies teacher, Tyler Nice has taught for twelve years at Thurston High School in Springfield, Oregon. He credits his teacher mother with sparking his interest in teaching, but he has persisted in the profession because of the pleasure he takes in “watching students grow intellectually. When they learn something for the first time, getting excited about it, I get excited.”

Modest about his own achievements, Nice does not understate the importance of his profession. “An educated and engaged citizenry is essential to a properly functioning Republic,” Nice says, echoing many in the founding generation. “Therefore, social studies teachers are the very foundation of our civic project. I consider my job among the most important in the country.”

What Attracted Nice to MAHG: Its Uniquely Hybrid Design

After being awarded a James Madison Foundation fellowship which would fund his Masters studies, Nice enrolled in the MAHG program, finding it the only program in the country that granted a hybrid degree combining history and political science. Earning the MAHG degree qualified Nice to teach both US History and US Government in the “College Now” program of his high school, which gives students early college credits through a cooperative program with Lane Community College. This year, Nice will undertake an additional dual enrollment course in Ethnic Studies.

“I’m really happy I did enroll in MAHG, not merely because it gave me the dual qualification in history and government,” Nice says. “The program was awesome. I would love to be able to teach my own classes in just the same way that the MAHG program works”—that is, with students usually reading primary documents in their entirety and discussing them in detail. “But some students in my classes are limited in how much they can actually read and understand; they lack the historical background or the reading skills. So I have to whittle the documents down” to the portions students can focus on without becoming discouraged.

Fairness to Students, to the Past and to the Future

Still, Nice designs his courses to accomplish what MAHG courses aim to do: to guide students in a careful exploration of political decision-making in a complex world.

“When we neglect the complexity of historical individuals and events in our teaching,” Nice says, “we insult our students. What we’re saying is, ‘you aren’t smart enough to wrestle with the historical reality. I’m giving you a simplified version, because that’s all you can handle.’ I don’t think that’s fair to the kids. I don’t think it’s fair to the people who lived before us. And I don’t think it’s fair to our republic. We need voters who are thoughtful”—who can wrestle with the challenges of democratic life.

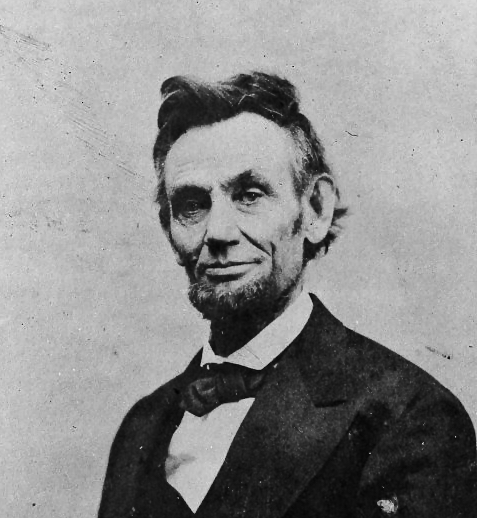

Among other skills, future voters must learn to assess the principles and convictions of those who run for office. A lesson plan Nice designed—the one he included among materials Gilder Lehrman award nominees are asked to submit—addresses this part of a citizen’s education. It focuses on one of America’s most admired leaders, Abraham Lincoln.

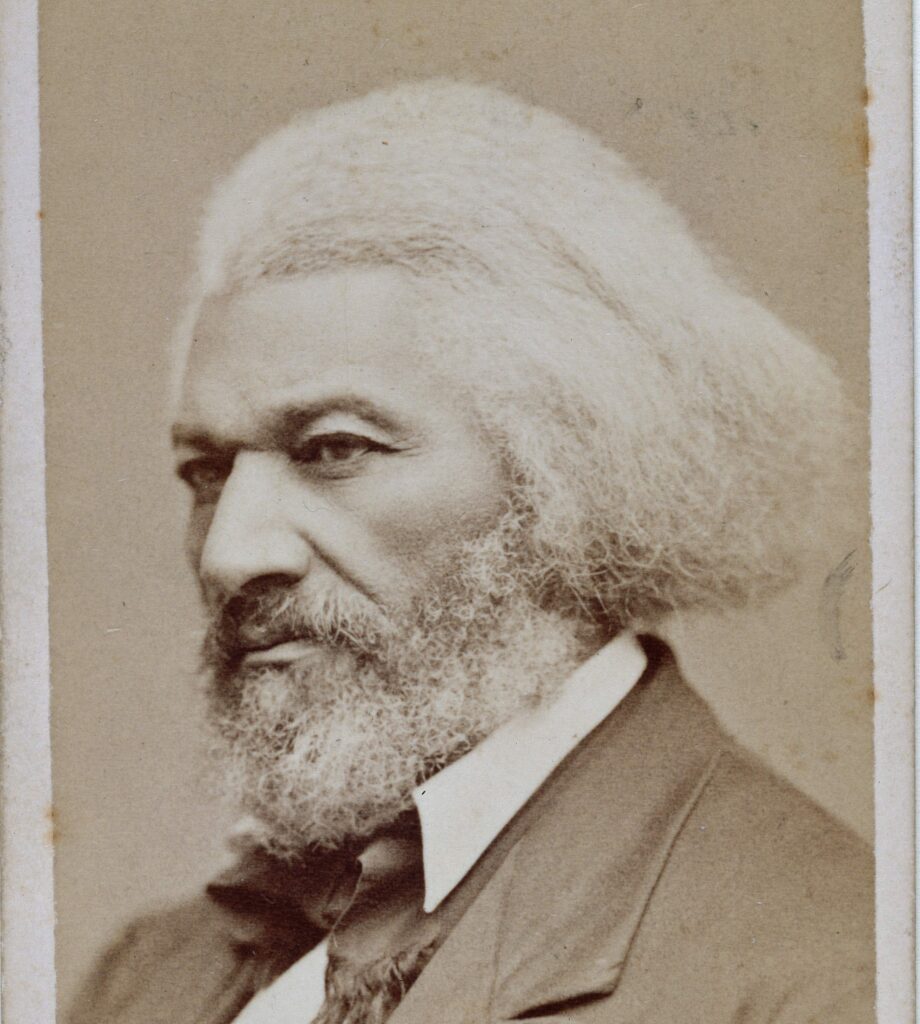

To frame the lesson, Nice uses a speech delivered by Frederick Douglass in 1876, at the unveiling of the Freedmen’s Memorial to Lincoln. The memorial was commissioned and entirely paid for by African Americans, who wished to honor Lincoln for accomplishing the abolition of slavery.

Assessing Lincoln’s Commitment to Racial Equality

Before praising the actions Lincoln took to dismantle the slave system, as well as the virtues that enabled Lincoln to do what no other leader had been able to do, Douglass announces a “truth” he thinks his largely black audience needs to hear: “Abraham Lincoln was not, in the fullest sense of the word, either our man or our model. In his interests, in his associations, in his habits of thought, and in his prejudices, he was . . . . preeminently the white man’s President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men.”

Nice asks students to consider whether Douglass’s assessment of Lincoln is fair. He gives them excerpts from 16 different documents from throughout Lincoln’s life. In each excerpt, Lincoln states his views on race and slavery. “I think I found all these documents in the online library of Teaching American History,” Nice said. “It’s fascinating to go through them. There is a lot to celebrate in Lincoln’s words. He clearly finds slavery repugnant.” He offers incisive arguments demonstrating the immorality of slavery and revealing the slaveholders’ own awareness that slavery is wrong.

“Yet Lincoln makes other comments that are hard to reconcile” with our image of the liberator president. In one speech he seems to affirm the prejudice, common among whites of his era, that blacks are inferior to whites. In a letter written early in his presidency, he announces that his priority is to save the union, and “not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.”

Admiration that Acknowledges Complexity

The latter statements evoke a range of reactions. “When kids read them, their eyebrows go up. Prior to this, I don’t think that they have ever viewed Lincoln as capable of such words. Some reject Lincoln outright from that point on.” Others struggle to integrate the quotations into their understanding of Lincoln, finally concluding that the remarks we find morally questionable reveal “Lincoln’s pragmatism.” (That Lincoln is a pragmatist is Nice’s own view.) “Other students say, ‘This doesn’t change how we should view Lincoln. He still did a great thing, and we should celebrate him.’”

Nice doesn’t expect students to land on the same conclusions. “I just want them to read Lincoln’s actual words, then use their brains and critical thinking skills to determine what they think for themselves.” Yet ultimately, he thinks, “when we look at somebody like Lincoln in a realistic way, it doesn’t diminish him.” Rather, looking at the complexities of Lincoln’s character “makes him more real. Our admiration for him becomes more robust.”

History education that prepares young Americans to undertake their responsibilities as citizens should teach “the values and goals of the American founding,” Nice says. This education entails “understanding the ways in which we’ve been successful in establishing those goals and values, and also the extent to which we’ve not yet succeeded.” Although the project of the founders is not yet complete, “their principles still exist. America is very much a project that we’re still working on.”

In his lesson plan, Nice excerpted portions of these documents by Abraham Lincoln:

- Protest in Illinois Legislature on Slavery, 1837.

- Letter to Mary Speed, 1841.

- A Bill for Abolishing Slavery in the District of Columbia, 1849.

- Eulogy of Henry Clay, 1852.

- Peoria Speech, 1854.

- Fragment on Slavery, 1854.

- Ottawa Debate with Stephen Douglas, 1858.

- Letter to Alexander Stephens, 1860.

- First Inaugural Address, 1861.

- Letter to Horace Greeley, 1862.

- Emancipation Proclamation, 1863.

- Gettysburg Address, 1863.

- Letter to Albert Hodges, 1864.

- Second Inaugural Address, 1865.

- Last Public Address, 1865.

Nice has graciously offered to share his lesson plan with TAH.org readers.