World War II

At 6 am on December 7, 1941, two consecutive waves of Japanese bombers, torpedo planes, and dive-bombers attacked the Pearl Harbor naval station on the Hawaiian island of Oahu. The attack on Pearl Harbor was part of a coordinated Japanese assault throughout the Pacific that also targeted the Philippines, Guam, and Hong Kong (See “Reacting to Pearl Habor“). The United States declared war against Japan the next day. “There is no blinking at the fact that our people, our territory, and our interests are in grave danger,” President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) told the nation. Four days later Germany and Italy declared war on the United States. The nation was now at war on two fronts, fighting determined and capable enemies.

The attack on Pearl Harbor was the culmination of a decade of tension between Japan and the United States. President Roosevelt tried to use a series of escalating sanctions to curtail Japan’s ambitions to extend its territorial control throughout Asia. Western nations, including the United States, had little interest in ceding their colonies or overseas markets to Japan. In the end, Japan elected to push out Western imperial nations by force.

The Japanese attack unified the nation, ending two years of debate over whether or not the wars in Europe and the Pacific were America’s wars to fight. Most pre-war discussion, however, had focused on how to respond to German, not Japanese, aggression. The prevailing feeling that it had been a mistake to get involved in World War I led to the adoption of a strict policy of neutrality in the 1930s (See the Neutrality Act of 1935 and Clark). After Hitler’s 1939 attack on Poland ignited World War II, Roosevelt struggled to reconcile the nation’s desire to help Great Britain defeat Nazi Germany with the policy of official neutrality. FDR endorsed sending economic aid to Great Britain as the best way to stay out of the war, arguing that without this American lifeline Great Britain would succumb to Nazi Germany (See “President Roosevelt Defends Lend-Lease” and “Arsenal of Democracy“). Charles Lindbergh, the most prominent member of the America First movement, openly challenged FDR’s claim that Nazi Germany posed a direct threat to the United States. These criticisms forced FDR to proceed cautiously, even as he aligned the United States more closely ideologically (See “The Four Freedoms” and “The Atlantic Charter“) and militarily (See Roosevelt) with Great Britain. By the fall of 1941, the majority of Americans supported FDR’s decision to shoot on sight German submarines trying to sink British merchant ships transporting American goods. Critics continued to attack FDR’s gradual abandonment of neutrality (See Taft), but Pearl Harbor ended all debate.

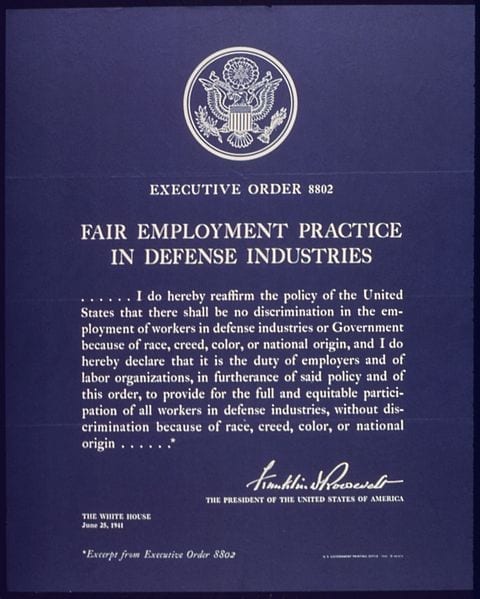

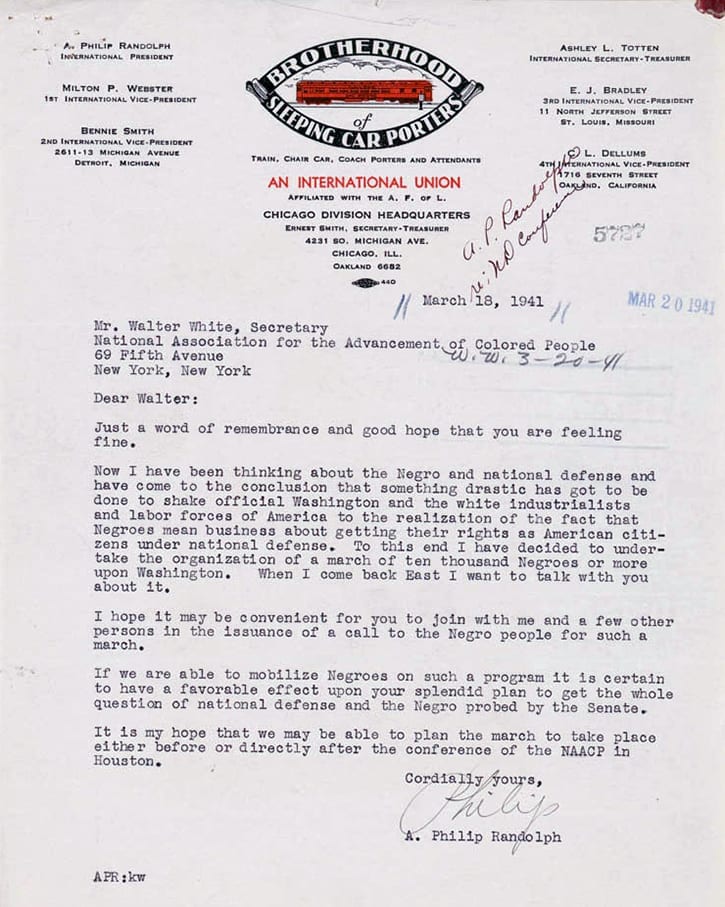

Even before the declarations of war, American society was changing as a result of overseas conflicts. A peacetime draft was introduced in 1940, and the exploding war trade pulled migrants to major cities in search of well-paying jobs. Both developments concerned African Americans who worried that racial discrimination would prevent them from having equal opportunities in the military and defense industries. FDR managed to halt a threatened March on Washington by promising access to high-paying defense jobs (See Roosevelt), while First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt offered more adamant support for racial equality by supporting the training of black military pilots (See Roosevelt). Throughout the war African Americans challenged segregation in the military and on the home front, racial discrimination in the workplace and housing market, and the seating of German POWs in restaurants while black soldiers were turned away (See Randolph, Roosevelt, and Trimmingham).

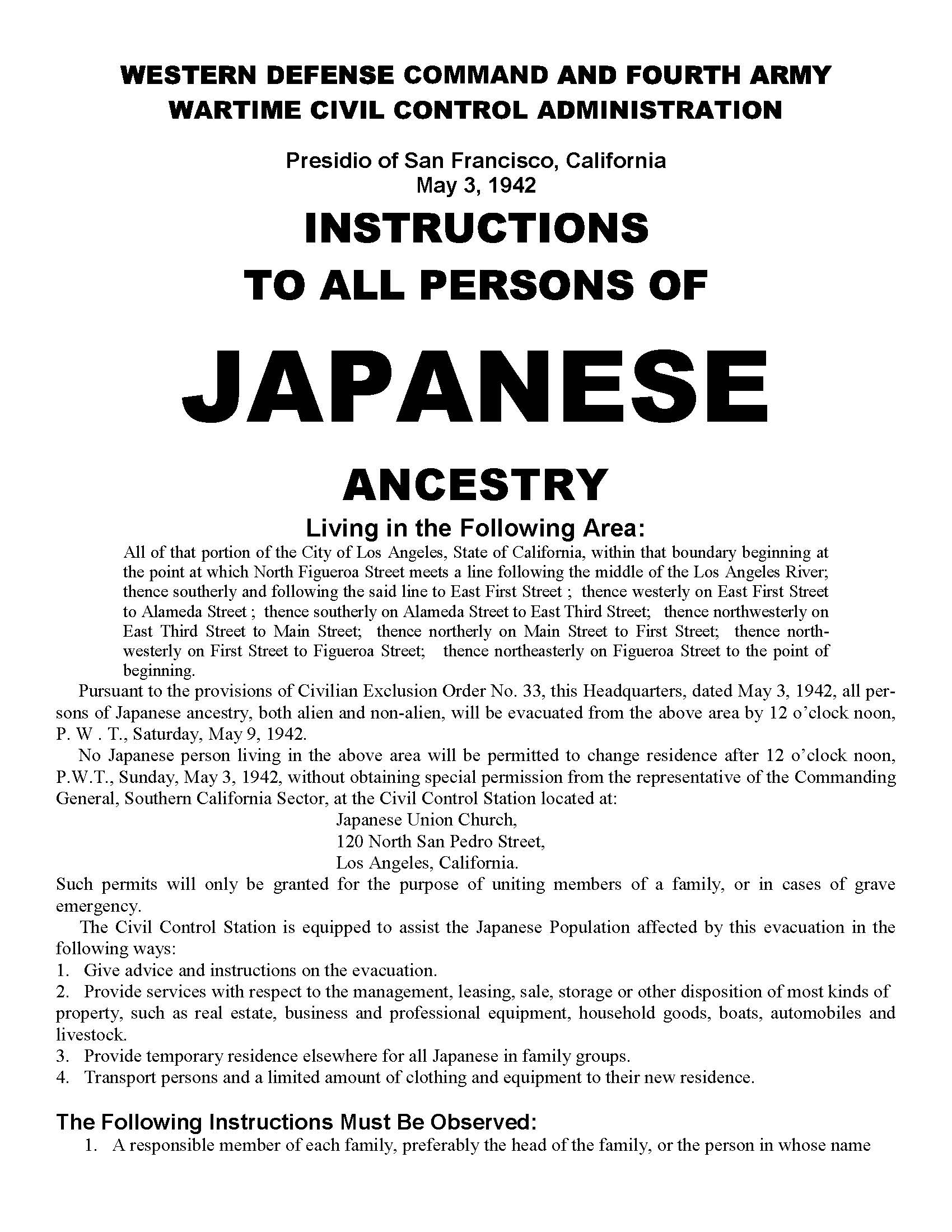

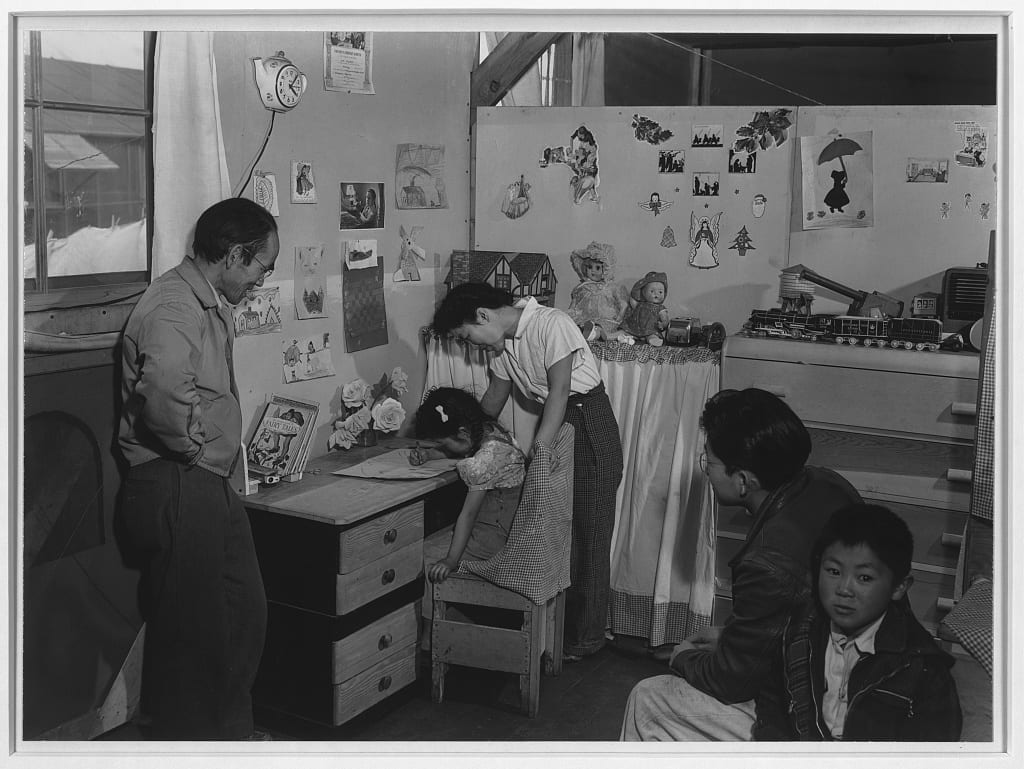

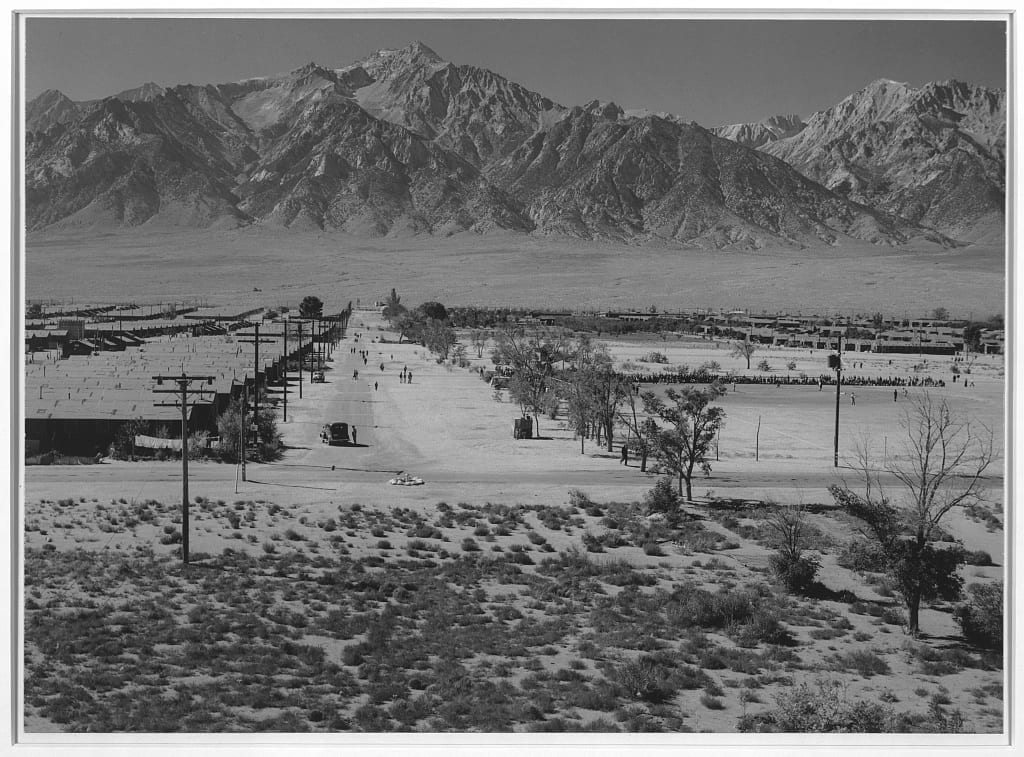

Eager for explanations after the attack on Pearl Harbor, some Americans suspected that Hawaiian residents of Japanese ancestry must have helped Japan. Prejudice against Asian Americans was not new, but the war amplified fears that Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans were disloyal. In the winter of 1942, FDR authorized their exclusion from the West Coast, and soon the War Relocation Authority was overseeing the removal of 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry to internment camps (See Roosevelt and “Japanese American Evacuation“). Once in the camps, Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans struggled to retain a semblance of normal life, and photographs offer some insight into their experiences (See Adams). Legal challenges to the Japanese internment reached the Supreme Court, which in 1944 upheld the constitutionality of the removal process without ruling directly on the constitutionality of internment in Korematsu v. US.

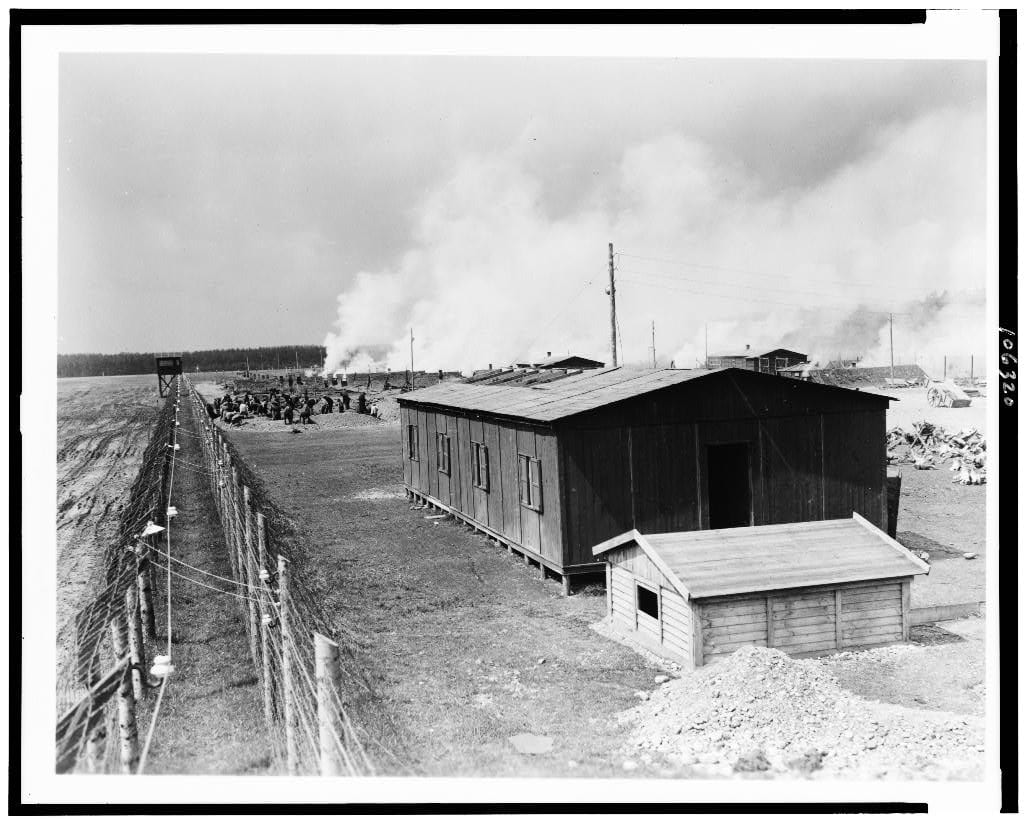

In writing the majority decision for Korematsu, Justice Hugo Black noted that “we deem it unjustifiable” to call the internment camps “concentration camps with all the ugly connotations that term implies.” His remark revealed that by 1944, Americans were well aware of Adolph Hitler’s plan to exterminate European Jews. The first news of the Final Solution reached Washington, D.C. in 1942, shortly after the German decision to initiate a systematic genocide to replace uncoordinated mass killings (See “First News of the Final Solution“). By 1944, American bombers were in range of the Auschwitz extermination camp in Poland but the military decided against bombing the gas chambers and crematorium, a decision that proved controversial (See “Stopping the Holocaust“). Instead, after Germany surrendered on May 7, 1945 the United States took the lead in organizing the postwar Nuremburg Trials to punish Nazi perpetrators for crimes against humanity (See Jackson).

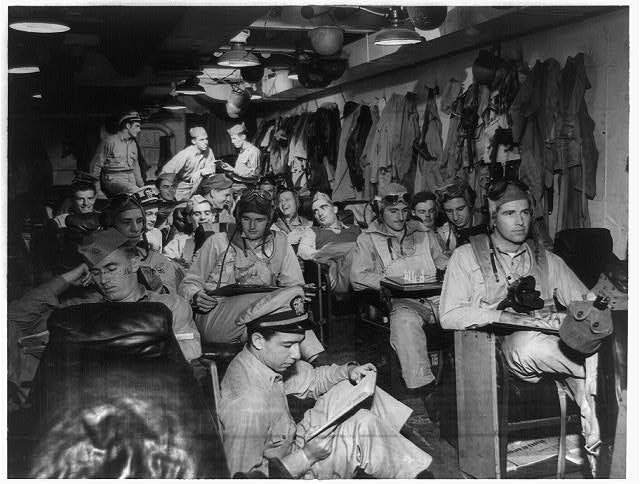

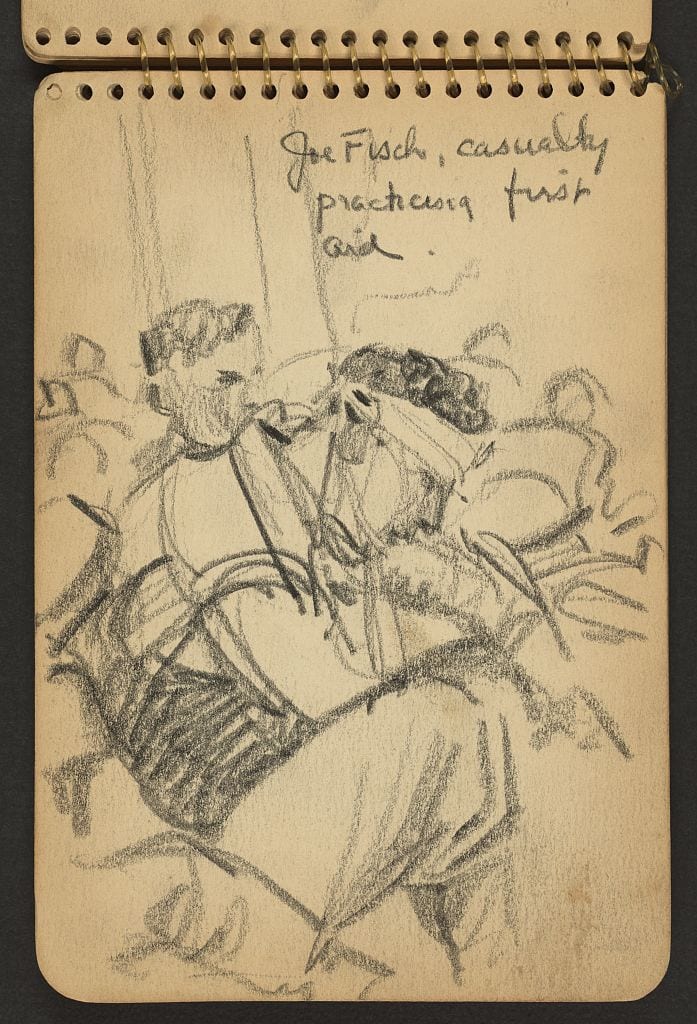

Of course, before it could try enemy leaders in Germany (and also Japan) for war crimes, the United States and its allies had to win victory on both fronts. Mobilizing the nation’s manpower meant recruiting men and women to serve the war effort in a multitude of ways. Eventually, over 16 million men served in the armed forces, a figure that included 10 million draftees. The military suffered approximately 291,000 deaths and 670,000 wounded. Almost 350,000 women served in the armed forces, including 150,000 women in the Women’s Army Corps who served as radio operators, clerks, technicians, and auto mechanics (See “Questions and Answers About the WAAC“). Three million civilian women joined the 16 million already in the workforce, the highest number of paid female workers yet recorded. Would these experiences working in civilian factories or serving in uniform permanently change the role of women in society? This question was anticipated and discussed even before the war was officially over (See “Do You Want Your Wife to Work After the War?“).

For men on the front lines, in Europe and in the Pacific, victory came with a high cost. Nearly two-thirds of the men who died in combat were killed in 1944 and 1945. The closer the Allies got to defeating Japan and Germany, the harder these enemy armies fought. The wartime diary of James J. Fahey and dispatches by war correspondent Ernie Pyle reveal the emotional and psychological side of combat. The differing leadership styles of General Dwight D. Eisenhower in Europe and General Douglas MacArthur in the Pacific offer a study in contrasts, yet each proved inspiring to the men under their command.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt did not live to see the end of the war. When he died of a cerebral hemorrhage on April 12, 1945, Harry S. Truman became president. He soon learned of a four-year secret weapons program called the Manhattan Project that was attempting to produce an atomic bomb. In July, the United States successfully tested its first atomic bomb in the New Mexico desert. Upon hearing the news, Truman issued a veiled ultimatum to Japan to immediately surrender or suffer immense destruction (See Potsdam Declaration). On August 6, 1945 the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan, killing 80,000 people. “I shall give further consideration and make further recommendations to the Congress as to how atomic power can become a powerful and forceful influence towards the maintenance of world peace,” Truman told the American people while announcing the attack. Three days later, a second nuclear bomb dropped on Nagasaki killed 35,000 people. Japan surrendered on August 14, 1945.

Victory on the battlefield against Japan and Germany did not bring certainty that years of peace would follow. Amid the celebrations, a host of new anxieties arose. What would the existence of atomic bombs mean for the future? US investigators offered one answer when they insisted that surveying the devastation in Hiroshima and Nagasaki would help Americans devise ways to defend their cities from similar attacks. World War II was over, but the nuclear age had begun.

US Neutrality

Neutrality Act of 1935 (August 31, 1935)

Bennett Champ Clark, A Senator Defends the First Neutrality Act (December 1935)

Franklin D. Roosevelt, President Roosevelt Defends Lend-Lease (December 17, 1940)

Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Arsenal of Democracy” Fireside Chat (December 29, 1940)

Franklin D. Roosevelt, “The Four Freedoms” (January 6, 1941)

Gallup Polls (January 1940 – January 1941)

Charles Lindbergh, “America First” (April 23, 1941)

Franklin D. Roosevelt, Fireside Chat on the Greer Incident (September 11, 1941)

Robert A. Taft, “Repeal of Neutrality Act Means War” (October 28, 1941)

Gallup Polls (April – October 1941)

Entering the War

Claude R. Wickard, Reacting to Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941)

Franklin D. Roosevelt, “A Date Which Will Live in Infamy” (December 8, 1941)

African Americans and the Double-Victory Campaign

Eleanor Roosevelt, The First Lady Visits Tuskegee (April 1, 1941)

Franklin D. Roosevelt, Executive Order 8802 – Prohibition of Discrimination in the Defense Industry (June 25, 1941)

A. Philip Randolph, “Why Should We March?” (November 1942)

Franklin D. Roosevelt, Executive Order 9346 – Establishing a Committee on Fair Employment Practice (May 27, 1943)

Corporal Rupert Trimmingham’s Letters to Yank Magazine (April 28, 1944 and July 28, 1944)

Japanese-American Internment

Franklin D. Roosevelt, Executive Order 9066 – Resulting in the Relocation of Japanese (February 19, 1942)

Japanese-American Evacuation (April – May, 1942)

Ansel Adams, Manzanar: Excerpt from Born Free and Equal (1944)

Korematsu v. US (December 18, 1944) On the Battlefront

James Fahey, Pacific War Diary (1942 – 1945)

Ernie Pyle, “The Death of Captain Waskow” (January 10, 1944)

Dwight D. Eisenhower, D-Day Statement to the Allied Expeditionary Force (June 5 – 6, 1944)

General Douglas MacArthur, Radio Address Upon Returning to the Philippines (October 20, 1944)

Women

United States Army Women’s Auxiliary Corps, Questions and Answers About the WAAC (1943)

G.I. Roundtable Series, “Do You Want Your Wife to Work After the War?” (1944)

The Holocaust

First news of the Final Solution (August 10 – 11, 1942)

Stopping the Holocaust (August 9 and August 14, 1944)

Justice Robert H. Jackson, Report on the Nuremburg Trials (October 7, 1946)

The Atomic Bomb

Potsdam Declaration (July 26, 1945)

Harry S. Truman, Press Release Alerting the Nation About the Atomic Bomb (August 6, 1945)

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, The Effects of Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (July 1, 1946)

For each of the Documents in this collection, we suggest below in section A questions relevant for that document alone and in Section B questions that require comparison between documents.

1. Neutrality Act of 1935 (August 31, 1935)

A. What actions did the Neutrality Act specifically prohibit? How were such restrictions meant to protect American neutrality? What potential problems might arise with these restrictions?

B. On what grounds did Senator Bennett Champ Clark argue that this first Neutrality Act was insufficient?

2. Bennett Champ Clark, A Senator Defends the First Neutrality Act (December 1935)

A. What conclusions did Clark draw from the nation’s experience in World War I? How did he characterize the munitions industry in the United States? What steps did he believe the United States must take to maintain strict neutrality?

B. How is Clark’s negative view of the impact of war on American society echoed in Charles Lindbergh’s 1941 “America First” address?

3. Franklin D. Roosevelt, President Roosevelt Defends Lend-Lease (December 17, 1940)

A. How did Roosevelt characterize Lend-Lease in these remarks to the press? How did he characterize America’s experience in World War I?

B. Both Senator Clark and President Roosevelt claimed that they wanted to avoid fighting another war. What different approaches did they take to meeting that goal?

4. Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Arsenal of Democracy” Fireside Chat (December 29, 1940)

A. Why, according to Roosevelt, do the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans no longer guarantee the safety of the United States? How did he characterize noninterventionists and the “America First” movement? Why were the Nazis a unique threat to world civilization? How did Roosevelt propose that the United States help Great Britain?

B. Are Roosevelt’s proposals in keeping with the spirit of the Neutrality Acts (See The Neutrality Acts and Bennett)?

5. Franklin D. Roosevelt, “The Four Freedoms” (January 6, 1941)

A. What are the Four Freedoms? According to Roosevelt, how do they define the “democratic way of life” in the United States? What connections did Roosevelt make in this speech between his domestic and foreign policies?

B. Consider this speech alongside Roosevelt’s press conference on Lend-Lease and his Arsenal of Democracy fireside chat. How did Roosevelt build a coherent foreign policy through his various addresses to the nation?

6. Gallup Polls (January 1940 – January 1941)

A. How did Americans’ views change over time about the likelihood of the United States entering World War II? Did the questions Gallup asked shape the responses given? What accounts for these shifting views?

B. Consider the polls before and after Roosevelt’s Lend-Lease proposal on December 17, 1940 and his Arsenal of Democracy Speech on December 29, 1940. To what extent was Roosevelt constrained by these polls? In what respects was he responding to these polls? How was he shaping public opinion? Lend-Lease was approved in March 1941. Consider these same questions for the polls before and after its approval (See Gallup Polls 1941).

7. Eleanor Roosevelt, The First Lady Visits Tuskegee (April 1, 1941)

A. What accomplishments at Tuskegee did Eleanor Roosevelt highlight, and why did she emphasize these particular accomplishments? What message did she send by having her photograph taken before her airplane ride?

B. How does Tuskegee’s approach to improving the lives of African Americans compare to the tactics of the March on Washington Movement?

8. Charles Lindbergh, “America First” (April 23, 1941)

A. Why did Lindbergh believe that the United States would lose if it decided to enter the European War? Why did he call his recommendation a policy of independence, not isolationism? What did Lindbergh mean when he said, “Practically every difficulty we would face in invading Europe becomes an asset to us in defending America.”

B. Compare this speech to Roosevelt’s “Arsenal of Democracy” speech. How does Lindbergh’s view of how oceans impact national security differ from Roosevelt’s perspective? What actions did each speaker encourage on the part of the general public? Is there something especially “democratic” about either or both appeals?

A. What measures did Executive Order 8802 prescribe to address racial prejudice? What problems did it not address?

B. How did Executive Order 8802 strengthen the claims that FDR made about democracy in the Four Freedoms address and the Atlantic Charter?

10. The Atlantic Charter (August 14, 1941)

A. What type of partnership did the Atlantic Charter create between the United States and Great Britain?

B. How are the themes of Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms speech reiterated in the Atlantic Charter? What objections might members of the “America First” Movement make to the Atlantic Charter?

11. Franklin D. Roosevelt, Fireside Chat on the Greer Incident (September 11, 1941)

A. Why should Americans care about the Greer attack, according to Roosevelt? What did he believe would happen to the United States in a Nazi-dominated world? Why did he reject a strategy of diplomacy and appeasement?

B. How did Roosevelt address the likely objections of non-interventionists

like Lindbergh in explaining his decision to protect merchant ships from other nations?

12. Robert A. Taft, “Repeal of Neutrality Act Means War” (October 28, 1941)

A. What objections does Taft raise to Roosevelt’s exercise of executive power in his foreign policy? Which policies is he specifically criticizing? Why isn’t he concerned about shifts in public opinion?

B. According to Gallup poll results, how popular are Taft’s views in 1940? In 1941? What counter argument does Roosevelt present in his Greer incident speech?

13. Gallup Polls (April – October 1941)

A. How would you characterize the state of American public opinion concerning the war in Europe in the months before Pearl Harbor? What changes after the Greer incident in September 1941?

B. Are there significant differences in public opinion in 1941, as compared to 1940? After the Greer incident, how much public support does FDR have for his foreign policies?

14. Claude Wickard, Reacting to Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941)

A. How would you characterize the reactions of Roosevelt and other government officials in the immediate aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor? What questions immediately arose?

B. How does this private conversation compare with the public address Roosevelt gave the next day in his “Day of Infamy” Speech before Congress?

15. Franklin D. Roosevelt, “A Date Which Will Live in Infamy” (December 8, 1941)

A. What are the key points that Roosevelt wanted to convey in this brief address? Why did he focus exclusively on Japan, and not mention Germany at all?

B. How did Roosevelt indirectly address the concerns of noninterventionists like Charles Lindbergh in his speech?

A. What did the EO 9066 authorize? Why did it not mention Japanese Americans by name? Did the order establish internment camps?

B. How did the Supreme Court reaffirm the powers that EO 9066 gave military commanders to issue exclusion orders (See Korematsu v. US)?

17. Japanese-American Evacuation (April – May, 1942)

A. How much time were residents given to prepare for departure? What rules governed how much they could bring? What message does Lange’s photograph convey about the motivations behind the evacuation? Why would Lange photograph the exclusion order posted alongside air raid instructions? Does seeing the poster alone offer a different interpretation of the exclusion order?

B. What happened to Toyosaburo Korematsu when he failed to leave the excluded area? Why did he stay?

18. First news of the Final Solution (August 10 – 11, 1942)

A. How did Harrison’s reaction to the report of German plans to exterminate Jews differ from Elting’s reaction? How did each justify his reaction?

B. What key decisions did the United States make in responding to the Holocaust (See “Stopping the Holocaust” and Jackson?

19. James Fahey, Pacific War Diary (1942 – 1945)

A. How do Fahey’s views of the Japanese change during the course of his military service? What factors shaped his views during and after the war? How did Fahey’s combat experience shape his views of the Japanese? What key observations does he make about the character of the war in the Pacific? How does he explain men’s willingness to fight?

B. What is Fahey’s account of MacArthur’s return to the Philippines? What perspective do these two accounts give on the war in the Pacific?

20. A. Philip Randolph, “Why Should We March?” (November 1942)

A. What double-victory campaign were African Americans waging at home and overseas? Why did Randolph believe that a March on Washington Movement was needed? What would a “nonviolent demonstration of Negro mass power” accomplish?

B. How do the points in Randolph’s 1942 program build on his accomplishments in 1941 (See Roosevelt)?

A. What power to combat racial discrimination did EO 9346 give the Fair Employment Practices Committee? What potential problems would still remain? Why did EO 9346 also include language concerning labor unions?

B. How well did EO 9346 satisfy the demands of the March on Washington Movement?

22. United States Army Women’s Auxiliary Corps, Questions and Answers About the WAAC (1943)

A. What tactics does this pamphlet use to entice women into joining the WAACs? How do the questions reveal the anxieties women might have about joining? Did the invitation to women to serve in uniform during the war upend gender roles?

B. How did serving in the WAACs compare to working for the war effort at home (See “Do You Want Your Wife to Work After the War“)? Did men and women view female war work differently?

23. Ernie Pyle, “The Death of Captain Waskow” (January 10, 1944)

A. What emotions does Pyle’s story convey? Pyle’s story had to pass a censor; why would a military censor allow newspapers to publish this story?

B. How does Pyle’s account of combat deaths compare to James Fahey’s observations in his wartime diary?

24. Corporal Rupert Trimmingham’s Letters to Yank Magazine (April 28, 1944 and July 28, 1944)

A. What incident prompted Trimmingham to write his first letter? Why did he write his second letter?

B. On what points would Trimmingham and A. Philip Randolph agree? How do their approaches to solving the problem of racial discrimination differ?

25. Dwight D. Eisenhower, D-Day Statement to the Allied Expeditionary Force (June 5 – 6, 1944)

A. What is Eisenhower’s key message to troops before they attack? What different message does his second note convey? How do these documents influence your interpretation of the photo?

B. How do Eisenhower’s two messages compare to the message that MacArthur issued in the Philippines?

26. Stopping the Holocaust (August 9 and August 14, 1944)

A. What differing opinions do Frischer and McCloy give on the question

of bombing Auschwitz-Birkenau?

B. Which response to the Holocaust offered a stronger deterrent to genocide in time of war: the proposed bombing of Auschwitz-Birkenau or the postwar Nuremburg Trials?

27. Ansel Adams, Manzanar: Excerpt from Born Free and Equal (1944)

A. What do Adams’ photographs of Manzanar reveal about the internment experience? How does Adams’ text “instruct” readers on the meaning of his photographs? Why did he choose this title for his work? What was his purpose in publishing this book?

B. Compare the attitudes and actions of the Japanese-Americans in Adams’ book with those of Toyosaburo Korematsu. What are the differences and similarities?

28. General Douglas MacArthur, Radio Address Upon Returning to the Philippines (October 20, 1944)

A. What is the purpose of MacArthur’s opening line? What is his message to the Filipino people?

B. How does MacArthur’s view of the enemy compare to the description in James Fahey’s Pacific War Diary?

29. Korematsu v. US (December 18, 1944)

A. What is the key argument of the majority opinion? What are the key arguments of the two dissenting opinions? What is the core of their disagreement?

B. What was the significance of wartime protests by Japanese Americans and African Americans (See Randolph and Trimmingham) against violations of civil rights?

30. G. I. Roundtable Series, “Do You Want Your Wife to Work After the War?” (1944)

A. What are the key points made in defense of wives continuing to work after the war? What are the key points made against the wives continuing to work after the war?

B. This pamphlet purports to represent men’s views on women working. Compare this pamphlet to the one recruiting women into the Women’s Auxiliary Army Core. What concerns do women have about joining the military? As presented by the pamphlets, do men and women share any concerns about women working outside of the home – and, if so, to what extent are their concerns similar?

31. Potsdam Declaration (July 26, 1945)

A. How does Truman’s warning indirectly hint that the US has the atomic bomb? How did the Allies define the meaning of unconditional surrender for Japan? Which terms of surrender might Japan object to most? What incentives to surrender does the declaration give Japan?

B. How does this declaration apply the principles of the Atlantic Charter to the Pacific war?

32. Harry S. Truman, Press Release Alerting the Nation About the Atomic Bomb (August 6, 1945)

A. What points does Truman emphasize when explaining the development of the bomb? How does he justify its deployment? What does the existence of atomic bombs mean for the future?

B. Did the Potsdam Declaration adequately warn Japan of the risk of an atomic bomb attack?

A. What assumptions does the report make about the future defense needs of the United States? What specific suggestions does it make about how best to defend the nation in a world with nuclear weapons?

B. How does this discussion of defending the United States compare to the discussions before Pearl Harbor over how best to defend the nation from attack (See “President Roosevelt Defends Lend-Lease,” “Arsenal of Democracy,” “America First,” and The Atlantic Charter)?

34. Justice Robert H. Jackson, Report on the Nuremburg Trials (October 7, 1946)

A. What are the key accomplishments of the trials, according to Jackson? What makes it an historic moment in international law?

B. In his opinion in Korematsu v. US (1944), Justice Hugo Black objected to applying the label “concentration camp” to the camps that detained Japanese Americans within the United States. In what ways does Jackson’s report on the Nuremburg Trials support or refute Justice Black’s view?

Adams, Michael C. C. The Best War Ever: America and World War II. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994.

Blum, John Morton. V Was for Victory: Politics and American Culture During World War II. NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976.

The Bombing of Auschwitz: Should the Allies Have Attempted It? ed. Michael J. Neufeld and Michael Berenbaum. NY: St. Martin’s Press, 2000.

Daniels, Roger. Prisoners Without Trial: Japanese Americans in World War II. NY: Hill and Wang, 2004.

Dower, John. War Without Mercy: War and Power in the Pacific War. NY: Pantheon Books, 1986.

Fussell, Paul. Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War. NY: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Kennedy, David. Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945. NY: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Linderman, Gerald F. The World Within War: America’s Combat Experience in World War II. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Rosenberg, Emily. A Date Which Will Live: Pearl Harbor in American Memory. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003.

Weinberg, Gerhard L. A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.)