Great Depression and the New Deal

The late 1920s were a time of great optimism in the United States, and few in public life expressed this optimism more clearly than Herbert Hoover. Even before becoming president in 1928, Hoover was one of the most respected men in the country, if not the world. Born in a rural village in Iowa and orphaned at the age of nine, he earned an engineering degree from Stanford University. After graduation he began a career in mining, becoming a millionaire by launching successful operations in Australia, Asia, Africa, and Latin America. During and after World War I he organized a massive relief effort to feed starving people in war-torn Europe, and became an international celebrity in the process. Later, as secretary of commerce under Presidents Harding and Coolidge, he inaugurated the policy – which continues to this day – of collecting statistical data on unemployment. He sincerely believed that American individualism, supported by a dynamic federal government, could end the nation’s problems. As he put it in a campaign speech in 1928, the country had “come nearer to the abolition of poverty, to the abolition of fear of want, than humanity has ever reached before” (Speech on the “Principles and Ideals of the United States Government” (1928)).

On October 24, 1929 – only seven months after the start of Herbert Hoover’s presidency – the economic boom that had characterized so much of the 1920s came to an abrupt end. The stock market crashed, and the thousands of investors who had purchased stock on credit were asked to make good on their promise to pay. When they could not, they were forced to sell their stocks, so that securities prices continued to plummet over the next two weeks. For ten years thereafter, the country would continue to struggle through the worst economic crisis of its history – the Great Depression. Banks, threatened with insolvency, called in their loans; and businesses, cut off from their sources of capital, scaled back their operations. Over the next few years millions would be laid off from their jobs. This in turn made the situation worse, since unemployed people could not buy the sort of consumer goods – radios, washing machines, vacuum cleaners, and most importantly automobiles – that had sustained the economic growth of the 1920s. Throughout Hoover’s presidency, therefore, the economy continued to deteriorate.

Hoover believed that the severity of the crisis demanded a strong response by the federal government. He held a series of conferences with business and labor leaders in which he exacted promises not to reduce wages, even as profits fell (Statement announcing a Series of Conferences with Representatives of Business, Industry, Agriculture, and Labor (1929)). He authorized new federal public works projects, and urged states and localities to do likewise. He signed a new tariff bill designed to protect American agriculture and manufacturing from cheap foreign imports (Statement on the Signing of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff (1930); Speech on the Smoot-Hawley Tariff (1930)). Hoover also argued that capital had to be pumped into the economy so that business confidence would be restored and the unemployed put back to work. It was in this spirit that he established, with congressional approval, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) (Special Message to Congress on Economic Recovery Program (1932)). The RFC made loans to banks and other major financial institutions in the hope that they would, in turn, extend credit to corporations, allowing them to hire more employees, place new orders with other firms, and invest in new enterprises.

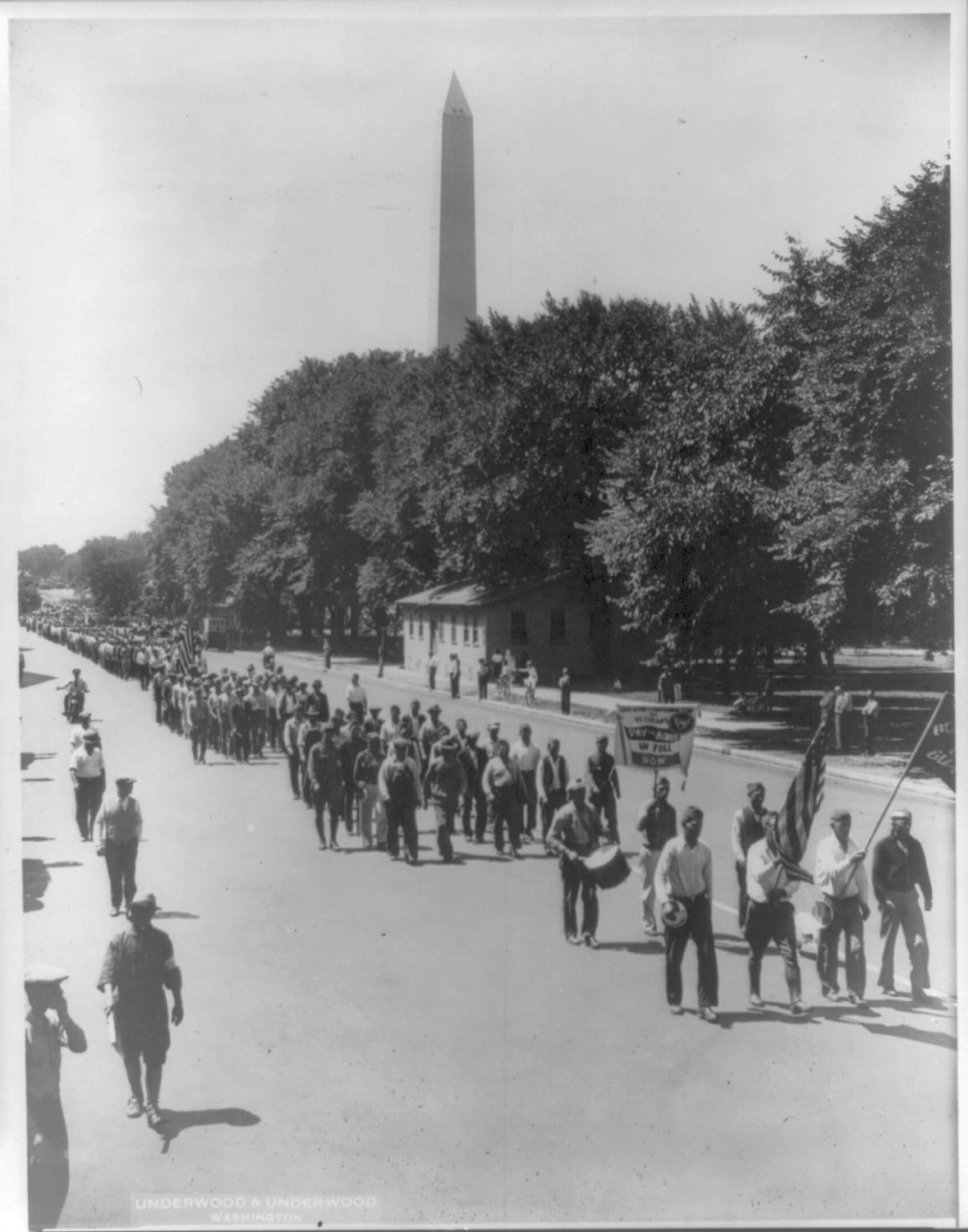

There were, however, certain steps that Hoover refused to take. He opposed the idea of making direct relief payments to individuals and families, fearing that this would foster an un-American dependence on the federal government (Press Statement on the Use of Federal Funds for Relief (1931)). He therefore vetoed legislation such as the Veterans’ Bonus Bill in 1931 and the Emergency Relief Bill in 1932 (Statement on the Dispersal of the Bonus Army (1932); Letter from Bonus Army Leader to President Hoover (1932); Veto of the Emergency Relief and Construction Bill (1932)). Moreover, he did not believe that the government should compete with private business, leading him to veto a congressional resolution to bring electricity to parts of the rural South (the Muscle Shoals joint resolution of 1931; see Veto of the Muscle Shoals Resolution (1931)). Finally, by 1932 Hoover was concerned that large budget deficits would impede recovery, so he tried to reduce overall federal spending.

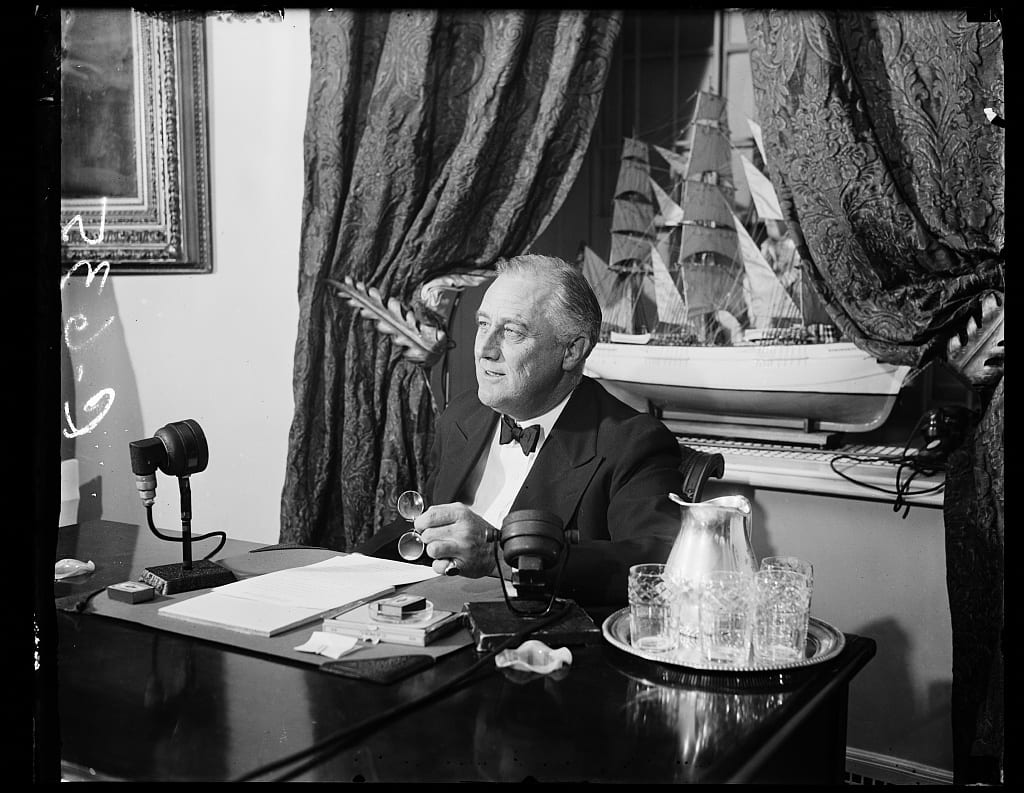

In spite of Hoover’s best efforts, the economy continued to slump. By late 1932 American banks were collapsing at an alarming rate, and some writers were beginning to call for the adoption of fascist or communist forms of government, such as those already in existence in Italy and the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, Hoover stood again as the Republican presidential nominee (Consequences of the Proposed New Deal (1932)). Very few people expected him to win; in fact, many people had come to believe that Hoover was simply not interested in the plight of ordinary people affected by the Depression. On Election Day, therefore, the voters turned overwhelmingly to the candidate of the Democratic Party, Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Unlike Hoover, Roosevelt had been in politics all his life. He had served in the New York state legislature, served as assistant secretary of the navy under Woodrow Wilson, and had run unsuccessfully for vice president on the Democratic ticket in 1920. In the early 1920s he was struck with polio, which left him paralyzed from the waist down, but a few years later he returned to public life and, in 1928, was elected governor of New York. During the 1932 presidential campaign he promised “a new deal for the American people,” but remained vague as to what this might mean (Acceptance Speech at the Democratic National Convention (1932); Commonwealth Club Address (1932)). Ultimately his victory resulted from Hoover’s extreme unpopularity and Roosevelt’s own cheery, optimistic style. As one Supreme Court justice put it, he may have been a “second-class intellect,” but he possessed a “first-class temperament.”1

In his inaugural address (First Inaugural Address (1933)), Roosevelt promised quick and dramatic action, and he was as good as his word. His election had coincided with the Democratic Party picking up 101 seats in the House of Representatives, strengthening their majority, and 12 in the Senate, giving them majority control in that house as well. Within the first hundred days of Roosevelt’s administration Congress passed an amazing number of bills that the president recommended or favored. In an attempt to increase the supply of money, he removed the dollar from the gold standard. An Agricultural Adjustment Act promised aid to farmers, but only on the condition that they reduce the amount of agricultural goods that they produced so that prices would rise. A public works bill authorized spending millions of dollars to put the unemployed to work. Another bill created the Tennessee Valley Authority, which brought the federal government into the provision of electricity to rural areas (Call for Legislation to Create the Tennessee Valley Authority (1933)); still another set up the National Recovery Administration, which oversaw the drafting of codes of conduct for various industries (“Fireside Chat” On the Purposes and Foundations of the Recovery Program (1933)). A few of the measures enacted during this period were extensions of Hoover’s own program; most, however, went far beyond, involving the federal government in areas that Hoover had insisted should remain within the scope of the private sector.

But although Roosevelt’s New Deal was wildly popular, it immediately drew fire from both the Right and the Left. Conservatives in both the Republican and Democratic parties claimed that the president was violating the Constitution (“Betrayal of the Democratic Party” (1936); “This Challenge to Liberty” (1935)). In several instances the Supreme Court agreed, striking down the National Industrial Recovery Act in 1935 (Schechter Poultry Corp v. United States (1935)), and the Agricultural Adjustment Act in the following year (United States v. Butler (1936)). Radicals, meanwhile, complained that Roosevelt was not doing enough to destroy the power of large banks and major corporations. Many on the Left demanded the nationalization of certain industries, the redistribution of wealth, and the creation of a full-scale social welfare system similar to those which had already been established in some European countries (Statement on the Share Our Wealth Society (1935); “A Third Party” (1936)).

When the early legislation of the New Deal failed to bring about economic recovery, Roosevelt himself veered sharply to the left. In 1935, he unveiled a series of new, more radical measures. These included nearly $1 billion in new spending on public works projects, new taxes that would fall on the wealthiest Americans, and a system of old-age insurance called Social Security. The National Labor Relations Act gave a tremendous boost to labor unions, by guaranteeing the right of workers to organize and requiring employers to bargain with union representatives. The Fair Labor Standards Act (Radio Address on Judicial Reorganization (1937)) abolished child labor and established a federal minimum wage. Many on the Left applauded these moves, while conservatives complained that Roosevelt was turning America into a socialist country (“Fireside Chat” On the Recession (1938)).

Although the promised recovery was slow to come, most Americans believed that the New Deal had improved their lives, so they gave it their enthusiastic support. Roosevelt managed to create a new coalition of reliably Democratic voters. Union workers in the Northeast joined with farmers from the South and Midwest, while African-Americans abandoned their traditional support for the Republican Party. When the president stood for reelection in 1936 against Alf Landon, the Republican governor of Kansas, the voters returned him to office in a landslide.

Roosevelt’s second term, however, would bring disappointment. His attempt to add more justices to the Supreme Court (“Fireside Chat” On the Plan for Reorganization of the Judiciary (1937)) was interpreted as an attack on the Constitution, leading Congress to hand the president his first serious political defeat. Moreover, the economy took a sudden downturn in 1937, underscoring Roosevelt’s failure to bring the country out of the Depression. The president’s efforts to drive more conservative members of his own party from Congress by campaigning for their opponents in the 1938 primaries (Speech on the Fair Labor Standards Act (1938)) met with disaster. Not only did nearly all of the conservatives survive the challenge, but they returned to Washington vowing revenge against the president who had tried to unseat them. The general elections compounded the president’s problems, as Republicans made major gains in Congress for the first time in ten years. Thereafter, Republicans were able to join with conservative Democrats to block further presidential initiatives.

By 1939, then, the New Deal had effectively ended, although the Great Depression went on. Gross domestic product did not exceed its 1929 level until 1941; unemployment remained above pre-Depression levels until 1943; and the stock exchange did not return to its pre-crash height until the late 1950s. The crisis – and the way the Hoover and Roosevelt administrations responded to it – would forever change the relationship between Americans and the federal government. Many of the agencies established during the 1930s, such as the National Labor Relations Board, the Securities Exchange Commission, the Federal Housing Administration, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and, of course, Social Security, continue to affect the lives of millions of people. More broadly, the Depression and the New Deal altered Americans’ expectations of the federal government. Before the 1930s few believed that Washington, DC was responsible for the nation’s economic health, or for the wellbeing of its citizens. Since that time almost no one denies it.

1. David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 100.

Hoover’s Response to the Economic Crisis

–President Herbert Hoover, Statement announcing a Series of Conferences with Representatives of Business, Industry, Agriculture, and Labor (November 15, 1929)

–President Herbert Hoover, Statement on the Signing of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff (June 16, 1930)

–Representative Jacob Milligan, Speech on the Smoot-Hawley Tariff (July 3, 1930)

–President Herbert Hoover, Press Statement on the Use of Federal Funds for Relief (February 3, 1931)

–President Herbert Hoover, Veto of the Muscle Shoals Resolution (March 3, 1931)

–President Herbert Hoover, Special Message to Congress on Economic Recovery Program (January 4, 1932)

–President Herbert Hoover, Veto of the Emergency Relief and Construction Bill (July 11, 1932)

–President Herbert Hoover, Statement on the Dispersal of the Bonus Army (July 29, 1932)

–Philo D. Burke, Letter from Bonus Army leader to President Hoover (July 29, 1932)

–President Herbert Hoover, Letter to Senator Simeon Fess (February 21, 1933)

The Election of 1932

–Franklin D. Roosevelt, Radio Address on “The Forgotten Man” (April 7, 1932)

–Franklin D. Roosevelt, Acceptance Speech at the Democratic National Convention (July 2, 1932)

–Franklin D. Roosevelt, Commonwealth Club Address (September 23, 1932)

–President Herbert Hoover, Consequences of the Proposed New Deal (October 31, 1932)

Roosevelt and the New Deal

–President Franklin D. Roosevelt, First Inaugural Address (March 4, 1933)

–President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Call for Legislation to Create the Tennessee Valley Authority (April 10, 1933)

–President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Fireside Chat” on the Purposes and Foundations of the Recovery Program (July 24, 1933)

–President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Speech to Congress on Foreign Trade (March 2, 1934)

–President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Speech to Congress on Social Security (January 17, 1935)

Opposition to the New Deal

–Representative James W. Wadsworth, Speech on Social Security (April 19, 1935)

–Senator Huey P. Long, Statement on the Share Our Wealth Society (May 23, 1935)

–Al Smith, “Betrayal of the Democratic Party” (January 25, 1936)

–Father Charles Coughlin, “A Third Party” (July 1, 1936)

–Herbert Hoover, “This Challenge to Liberty” (October 30, 1936)

–Representative Wade Kitchens, Speech on the Fair Labor Standards Act (May 16, 1938)

The Election of 1936 and the End of the New Deal

–Al Smith, “Betrayal of the Democratic Party” (January 25, 1936)

–President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Acceptance Speech at the Democratic National Convention (June 27, 1936)

–Father Charles Coughlin, “A Third Party” (July 1, 1936)

–Herbert Hoover, “This Challenge to Liberty” (October 30, 1936)

–President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Second Inaugural Address (January 20, 1937)

–President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Message to Congress on Establishing Minimum Wages and Maximum Hours (May 24, 1937)

–President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Fireside Chat” on the Recession (April 14, 1938)

–President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Fireside Chat” on “Purging” the Democratic Party (June 24, 1938)

Labor and the New Deal

–The Norris-La Guardia Act (March 23, 1932)

–“Black Labor and the Codes,” Editorial, Opportunity (August 1933)

–Mauritz A. Hallgren, “The Right to Strike,” The Nation (November 8, 1933)

–Senator Robert F. Wagner, Speech on the National Labor Relations Act (February 21, 1935)

–Edward Levinson, “Detroit Digs In” (January 16, 1937)

–Representative Wade Kitchens, Speech on the Fair Labor Standards Act (May 16, 1938)

Roosevelt and the Supreme Court

–Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States (May 27, 1935)

–United States v. Butler (January 6, 1936)

–President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Fireside Chat” on the Plan for Reorganization of the Judiciary (March 9, 1937)

–Senator Carter Glass, Radio Address on Judicial Reorganization (March 29, 1937) –President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Message to Congress on Establishing Minimum Wages and Maximum Hours (May 24, 1937)

African-Americans and the New Deal

–“Black Labor and the Codes,” Editorial, Opportunity (August 1933)

–E.E. Lewis, “Black Cotton Farmers and the AAA” (March 1935)

For each of the Documents in this collection, we suggest below in section A questions relevant for that document alone and in Section B questions that require comparison between documents.

Herbert Hoover, Speech on the “Principles and Ideals of the United States Government” (October 22, 1928)

A. What does Hoover regard as the dangers of the “projection of government in business”? What is Hoover’s definition of “liberalism”? What does he regard as the proper functions of government? What does Hoover mean by the “American system”?

B. How do Hoover’s views on the role of government differ from those of Franklin D. Roosevelt in his Commonwealth Club Address (1932)? How does his definition of “liberalism” differ from that of Roosevelt (Acceptance Speech at the Democratic National Convention (1932))? How does this campaign speech compare with Hoover’s later addresses (Consequences of the Proposed New Deal (1932); “This Challenge to Liberty” (1936))? Is there any evidence that his views changed over time?

President Herbert Hoover, Statement announcing a Series of Conferences with Representatives of Business, Industry, Agriculture, and Labor (November 15, 1929)

A. What does Hoover believe to be the cause of the economic crisis? What role does he envision the federal government playing in dealing with this problem?

B. How does Hoover’s response to the economic crisis compare to that made by Roosevelt in his Second Inaugural Address (1937)? How does Hoover’s interpretation of the causes of the crisis compare with that expressed in his Letter to Senator Simeon Fess (1933)?

President Herbert Hoover, Statement on the Signing of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff (June 16, 1930)

A. What reservations does Hoover seem to have about this particular bill? Why has he decided to sign it, despite his reservations?

B. How might Hoover respond to the claims made by Rep. Jacob Milligan (Speech on the Smoot-Hawley Tariff (1930))? How does this measure fit with Hoover’s understanding of the proper role of the federal government (“Principles and Ideals of the United States Government” (1928); Consequences of the Proposed New Deal (1932); “This Challenge to Liberty” (1936))? How do his views on trade compare to those of Roosevelt (Speech to Congress on Foreign Trade (1934))?

Representative Jacob Milligan, Speech on the Smoot-Hawley Tariff (July 3, 1930)

A. What does Milligan find so objectionable about the new tariff law? Why does he suggest that it would be more appropriately called the “HooverGrundy” bill?

B. How do Milligan’s views on trade differ from those of his fellow Democrat Roosevelt (Speech to Congress on Foreign Trade (1934))?

President Herbert Hoover, Press Statement on the Use of Federal Funds for Relief, February 3, 1931

A. What does Hoover see as the dangers in using federal money for “charitable purposes”? How does he prefer to see relief efforts handled? How does Hoover respond to the suggestion that he lacks “human sympathy for those who suffer”? Are there any circumstances in which he would approve the use of federal funds to assist those suffering from the economic crisis?

B. How do Hoover’s opinions on the use of federal funds for relief compare to those of Roosevelt, as seen in his Fireside Chats on the “forgotten man” and on the purposes of his recovery program (“The Forgotten Man” (1932); “Fireside Chat” On the Purposes and Foundations of the Recovery Program (1933)), and his proposed Social Security plan (Speech to Congress on Social Security (1935))?

President Herbert Hoover, Veto of the Muscle Shoals Resolution (March 3, 1931)

A. On what grounds does Hoover object to government operation of the Muscle Shoals facility? What does it tell us about his overall view of the role of government? What does he suggest as an alternative?

B. How do Hoover’s views on this subject compare to those of Roosevelt (Call for Legislation to Create the Tennessee Valley Authority (1933))?

President Herbert Hoover, Special Message to Congress on Economic Recovery Program (January 4, 1932)

A. What steps is Hoover calling on Congress to take to address the economic crisis? What, specifically, is the purpose of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation? Why does he compare the efforts to bring about recovery to “a great war”? Why does he believe it is possible for the United States to pursue recovery “independent of the rest of the world”?

B. How do Hoover’s proposals here line up with his views on the proper role of the federal government (“Principles and Ideals of the United States Government” (1928))? Does he seem to have changed his mind in any way? How does his use of the war analogy compare to that of Roosevelt (First Inaugural Address (1933))?

The Norris-La Guardia Act (March 23, 1932)

A. What reasoning does this document offer for why courts must not be allowed to issue injunctions against labor unions? What specific activities does the act protect against injunctions? Why do you think Hoover was willing to sign this piece of legislation?

B. Does Hoover’s approval of this bill conflict with his earlier stated views on the role of the federal government (“Principles and Ideals of the United States Government” (1928))? To what extent might the labor disputes described in “The Right to Strike” (1933); “Detroit Digs In” (1937) be attributed to this bill? How does Norris-LaGuardia compare with the National Labor Relations Act (Speech on the National Labor Relations Act (1935))?

Franklin D. Roosevelt, Radio Address on “The Forgotten Man”(April 7, 1932)

A. Who, according to Roosevelt, is “the forgotten man”? Which Hoover policies does he single out for criticism? What measures does he propose for solving the economic crisis?

B. How does this speech compare with his later campaign addresses (Acceptance Speech at the Democratic National Convention (1932); Commonwealth Club Address (1932))? How does it compare with his first inaugural address (First Inaugural Address (1933))? How does his vision of the role of government compare with that of Hoover (“Principles and Ideals of the United States Government” (1928); Consequences of the Proposed New Deal (1932))?

Franklin D. Roosevelt, Acceptance Speech at the Democratic National Convention (July 2, 1932)

A. What does Roosevelt regard as symbolic about his decision to travel to Chicago personally to accept his party’s nomination? How does he distinguish his own liberalism from both radicalism and reaction? What does Roosevelt see as the cause of the Depression? On what grounds does he criticize Hoover’s handling of the crisis?

B. How does Roosevelt’s definition of liberalism differ from that put forward by Hoover (“Principles and Ideals of the United States Government” (1928); Consequences of the Proposed New Deal (1932))? How does his explanation of the causes of the Depression compare with those of Hoover (Letter to Simeon Fess (1933))? How does his understanding of the U.S. economy differ from Hoover’s, as seen in Consequences of the Proposed New Deal (1932)?

President Herbert Hoover, Veto of the Emergency Relief and Construction Bill (July 11, 1932)

A. On what grounds does Hoover object to the use of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to provide federal loans to states, and to the general public? What does he suggest as an alternative arrangement?

B. Referring to Special Message to Congress on Economic Recovery Program (1932), would you say that Hoover was correct in asserting that this proposed use of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation was a radical departure from the agency’s intent? How might Roosevelt, in “The Forgotten Man” (1932); Commonwealth Club Address (1932) have been referring to Hoover’s veto of this bill?

President Herbert Hoover, Statement on the Dispersal of the Bonus Army (July 29, 1932)

A. How does Hoover defend the use of federal troops to disperse the Bonus Army? Based on the information Hoover had at his disposal, do you think his decision was justified?

B. How does this account of the dispersal of the Bonus Army compare with that of Philo T. Burke (Letter from Bonus Army Leader to President Hoover (1932))? Based on Roosevelt’s comments in “The Forgotten Man” (1932); Acceptance Speech at the Democratic National Convention (1932), do you think he would have acted differently if he had been president?

Philo D. Burke, Letter from Bonus Army leader to President Hoover (July 29, 1932)

A. What or whom does Burke blame for the plight of the country’s veterans? Why does he refer to Hoover as “Andy Mellon’s President”? Why does he believe that Hoover acted as he did toward the Bonus Army?

B. How does Burke’s account of the dispersal of the Bonus Army compare to that of Hoover (Statement on the Dispersal of the Bonus Army (1932))?

Franklin D. Roosevelt, Commonwealth Club Address (September 23, 1932)

A. Why, according to Roosevelt, was individualism appropriate in the late 18th and 19th centuries, but not in the 20th? What does he mean when he claims that “the day of enlightened administration has come”? Who or what does Roosevelt blame for the Depression?

B. How does Roosevelt’s interpretation of the problems facing the country compare with that of Hoover, (Consequences of the Proposed New Deal (1932); Letter to Simeon Fess (1933))? How does his analysis of the recent past differ from that put forward by Hoover (Consequences of the Proposed New Deal (1932))? How does his view of the country’s future differ from Hoover’s vision?

President Herbert Hoover, Consequences of the Proposed New Deal (October 31, 1932)

A. What does Hoover regard as the primary cause of the Depression? Why does he believe that it is more important to focus on the past thirty years, rather than the last three? Why does he believe that Roosevelt’s New Deal will be dangerous for the country?

B. How does Hoover’s account of the origins of the Depression compare with that of Roosevelt, (“The Forgotten Man” (1932); Acceptance Speech at the Democratic National Convention (1932); Commonwealth Club Address (1932))? How does this campaign address compare with his campaign speech in 1928 (“Principles and Ideals of the United States Government” (1928)), or his speech on behalf of Alf Landon in 1936 (“This Challenge to Liberty” (1936))?

President Herbert Hoover, Letter to Senator Simeon Fess (February 21, 1933)

A. Why is Hoover addressing this letter to Senator Fess? What, according to the president, accounts for the ups and downs of the economy since 1931? Why does he blame President-elect Roosevelt for the conditions prevailing in early 1933?

B. How does Hoover’s account of current economic conditions compare to the argument he makes in Consequences of the Proposed New Deal (1932)? How does his interpretation differ from that of Roosevelt (Acceptance Speech at the Democratic National Convention (1932); Commonwealth Club Address (1932))?

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, First Inaugural Address (March 4, 1933)

A. What does Roosevelt mean when he says that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself”? What actions does he say are necessary to solve the economic crisis? How and why does he use military analogies (“great army of our people”) to make his arguments?

B. How does Roosevelt’s use of the analogy of war compare to Hoover’s (Special Message to Congress on Economic Recovery Program (1932))? Does Roosevelt’s logic in this speech flow naturally from the claims he made (Commonwealth Club Address (1932))? How does the plan Roosevelt puts forward in his First Inaugural Address (1933) compare with the plan he outlines in his Second Inaugural Address (1937)?

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Call for Legislation to Create the Tennessee Valley Authority (April 10, 1933)

A. What good does Roosevelt see coming from government development of the Tennessee Valley Authority? What does he mean when he says that the country has “just grown”?

B. How does Roosevelt’s proposal compare to the Muscle Shoals bill vetoed by Hoover in 1931 (Veto of the Muscle Shoals Resolution (1931))? What does a comparison of these documents tell us about the ways in which each president regarded the role of the federal government? To what extent does this proposal reflect the goal of “enlightened administration” laid out by Roosevelt (Commonwealth Club Address (1932))?

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Fireside Chat” on the Purposes and Foundations of the Recovery Program (July 24, 1933)

A. What accomplishments does Roosevelt seem proudest of at this point in his presidency? What distinction does he draw between those measures that he views as “foundation stones” and the “links which will build us a more lasting prosperity”? How is the National Industrial Recovery Act supposed to work?

B. How do the measures listed here fit with the overall approach to governance laid out by Roosevelt (Commonwealth Club Address (1932); First Inaugural Address (1933))? How does Roosevelt’s presentation of the AAA and NIRA differ from the criticisms of these programs found “Black Labor and the Codes” (1933); Black Cotton Farmers and the AAA (1935); “Betrayal of the Democratic Party” (1936); Speech on the Fair Labor Standards Act (1938))?

“Black Labor and the Codes,” Editorial, Opportunity (August 1933)

A. What do the editors of Opportunity find objectionable about the National Industrial Recovery Act? Why do they believe that white as well black workers should be concerned about the codes that have been approved thus far?

B. Taken together with “Black Cotton Farmers and the AAA” (1935), why might African-Americans have had reason to be disappointed with the New Deal thus far? Why do you think they supported Roosevelt regardless? How does this criticism of the NIRA compare with those put forward by Al Smith (“Betrayal of the Democratic Party” (1936)) and Father Charles Coughlin (“A Third Party” (1936))?

Mauritz Hallgren, “The Right to Strike” The Nation (November 8, 1933)

A. Why, according to the author, is labor unrest on the rise in 1933? How does this wave of strikes differ from those of earlier eras? What challenge do they pose for the Roosevelt administration?

B. How might the Norris-La Guardia Act (1932) and the National Industrial Recovery Act (“Fireside Chat” On the Purposes and Foundations of the Recovery Program (1933)) have encouraged the rise in labor militancy? In what way would the National Labor Relations Act (Speech on the National Labor Relations Act (1935)) encourage this trend even further?

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Speech to Congress on Foreign Trade (March 2, 1934)

A. What did the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act propose to do? Why does Roosevelt believe that it will be beneficial? Why does he warn Congress that “quick results are not to be expected”?

B. How does Roosevelt’s understanding of international trade differ from Hoover’s (Statement on the Signing of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff (1930))? How does it compare to that of Rep. Jacob Milligan (Speech on the Smoot-Hawley Tariff (1930))?

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Speech to Congress on Social Security (January 17, 1935)

A. What does Roosevelt’s Social Security plan entail? How is it to be funded? Why does the president believe it is necessary?

B. How does this proposal fit in with Roosevelt’s call for “enlightened administration” in Commonwealth Club Address (1932)? How does the president’s view of Social Security compare with that of Rep. James Wadsworth, as expressed in Speech on Social Security (1935)?

Senator Robert F. Wagner, Speech on the National Labor Relations Act (February 21, 1935)

A. Why does Wagner believe that this bill is necessary? On what grounds does he claim that the bill is “novel neither in philosophy nor in content”? What misconceptions about the bill does he attempt to clear up?

B. In what sense does Mauritz Hallgren’s account of labor unrest (“The Right to Strike” (1933)) help us to understand why Roosevelt was hesitant to endorse the National Labor Relations Act? How does the act build on the Norris-La Guardia Act (1932) and the National Industrial Recovery Act (“Fireside Chat” On the Purposes and Foundations of the Recovery Program (1933))?

E.E. Lewis, “Black Cotton Farmers and the AAA” (March 1935)

A. How, according to Lewis, has the Agricultural Adjustment Administration disadvantaged black farmers? What special “handicaps” does the black farmer face that his white counterpart does not?

B. Taken together with “Black Labor and the Codes” (1933), why might African-Americans have had reason to be disappointed with the New Deal thus far? Why do you think they supported Roosevelt regardless? How does this criticism of the AAA compare with those put forward in United States v. Butler (1936)?

Representative James W. Wadsworth, Speech on Social Security (April 19, 1935)

A. What misgivings does Wadsworth have regarding how Social Security is to be funded? Why does he think it poses a danger to the republic? How does he predict the program will develop? Have his predictions come true?

B. How does this speech compare with Hoover’s invocation of “rugged individualism” in “Principles and Ideals of the United States Government” (1928)? Based on Commonwealth Club Address (1932) and Speech to Congress on Social Security (1935), how might Roosevelt respond to Wadsworth’s criticisms?

Senator Huey P. Long, Statement on the Share Our Wealth Society (May 23, 1935)

A. What does Long regard as the fundamental cause of the Depression? In what ways does he think the New Deal has fallen short? What does he propose as a remedy? How does he seek to justify his program?

B. How does Long’s critique of the New Deal compare with that of Father Coughlin in “A Third Party” (1936)? How does it compare with the criticisms made by Al Smith in “Betrayal of the Democratic Party” (1936), and by Hoover in “This Challenge to Liberty” (1936)?

Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes (May 27, 1935)

A. On what grounds does the Court find the NIRA unconstitutional? What do the justices think of the administration’s claim that the law was justified on the basis of the severity of the economic crisis? On what do they base their conclusion that the poultry code was not legal under the Commerce Clause of the Constitution?

B. Based on your reading of “Fireside Chat” Purposes and Foundations of the Recovery Program (1933), why do you think this decision was regarded as such a devastating blow to Roosevelt’s agenda? How does the reasoning in this case compare to that used by the Court in United States v. Butler (1936)?

Paul Taylor, “Again the Covered Wagon” (July 1935)

A. What motives led thousands of Americans to move to California in the mid-1930s? What challenges did they face when they arrived there? Why is their presence a matter of concern to more established residents of California?

B. How does the plight of the migrants compare to that of African Americans, as seen in “Black Labor and the Codes” (1933) and “Black Cotton Farmers and the AAA” (1935)?

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Annual Message to Congress (January 3, 1936)

A. What did Roosevelt mean when he spoke of an “economic constitutional order”? How would such an order differ from the one that existed when Roosevelt took office?

B. How does the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Butler (1936) affect the new order Roosevelt was trying to build? Are Al Smith’s criticisms of the New Deal (“Betrayal of the Democratic Party” (1936)) criticisms of this new economic order? What are Smith’s criticisms?

United States v. Butler, Associate Justice Owen J. Roberts (January 6, 1936)

A. On what grounds does the Court find the AAA unconstitutional? Why does so much of the decision rest on the definition of the term “general welfare”? Why do the justices regard it as a dangerous precedent?

B. How does the reasoning in this case compare to that used by the Court in Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States (1935)? Why do you think the Court was divided on this issue, whereas the decision in Schechter was unanimous? Which decision do you think was more painful to the administration, and why?

Al Smith, “Betrayal of the Democratic Party” (January 25, 1936)

A. In what ways does Smith believe that Roosevelt has not been faithful to the Democratic Party’s 1932 platform? Why does he think the New Deal is an example of socialism? What does he call on his fellow Democrats to do?

B. How does Smith’s critique of the New Deal compare to that of Hoover in “This Challenge to Liberty” (1936)? How does it compare to the criticisms by Huey Long in Statement on the Share Our Wealth Society (1935), and Father Coughlin in “A Third Party” (1936)?

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Acceptance Speech at the Democratic National Convention (June 27, 1936)

A. What was Roosevelt’s purpose in drawing a comparison between the Revolution in 1776 and his efforts since taking office? When Roosevelt spoke of a “rendezvous with destiny,” what did he mean?

B. Compare the argument and rhetoric of this speech with Roosevelt’s Commonwealth Club Address (1932). Has he changed his views or his manner of expressing them?

Father Charles Coughlin, “A Third Party” (July 1, 1936)

A. Why did Coughlin initially support Roosevelt and the New Deal? Why has he turned against them now?

B. How does Coughlin’s criticism of Roosevelt compare with that of Huey Long in Statement on the Share Our Wealth Society (1935)? Both Coughlin and Al Smith (“Betrayal of the Democratic Party” (1936)) cite the Democratic Party Platform of 1932. How does Coughlin’s understanding of that document compare with Smith’s?

Herbert Hoover, “This Challenge to Liberty” (October 30, 1936)

A. What does Hoover find so objectionable about the New Deal? Why does he believe that it is a “repudiation of democracy”? How does he defend his own tenure as president? What does Hoover mean when he says that the nation needs not only economic recovery, but “moral recovery”?

B. How does this speech compare with what Hoover told listeners in Consequences of the Proposed New Deal (1932)? How does it compare with the criticism made by Al Smith in “Betrayal of the Democratic Party” (1936)? How does critique differ from those of Huey Long (Statement on the Share Our Wealth Society (1935)) and Father Coughlin (“A Third Party” (1936))?

Edward Levinson, “Detroit Digs In” (January 16, 1937)

A. What was particularly controversial about the strike against General Motors? What measures did the company take to break the strike? Why did the strike ultimately succeed?

B. How does the labor activity described here compare to that described in “The Right to Strike” (1933)? How might the National Labor Relations Act (described by Sen. Robert Wagner in Speech on the National Labor Relations Act (1935)) have paved the way for this sort of strike?

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Second Inaugural Address (January 20, 1937)

A. How does Roosevelt attempt to show that the New Deal is in line with established constitutional tradition? Why do you think he feels the need to do this? What does Roosevelt consider the greatest accomplishments of his first term? What goals does he set for himself for his second term?

B. How does this speech compare with Roosevelt’s First Inaugural Address (1933) and his 1936 State of the Union Address (Annual Message to Congress (1936))? In what sense might it be regarded as a response to his recent critics – Huey Long (Statement on the Share Our Wealth Society (1935)), Al Smith (“Betrayal of the Democratic Party” (1936)), Father Coughlin (“A Third Party” (1936)), and Herbert Hoover (“This Challenge to Liberty” (1936))?

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Fireside Chat” on the Plan for Reorganization of the Judiciary (March 9, 1937)

A. Why does Roosevelt think that the federal judiciary needs to be changed? How does he invoke the Constitution to defend this? What is his proposal, and on what grounds does he seek to justify it?

B. What examples from Schechter Poultry Corp v. United States (1935); United States v. Butler (1936) might Roosevelt cite of “outdated” legal thinking that judicial reorganization seeks to correct? How might Roosevelt respond to the accusations made by Sen. Carter Glass in Radio Address on Judicial Reorganization (1937)?

Senator Carter Glass, Radio Address on Judicial Reorganization (March 29, 1937)

A. On what grounds does Glass attack Roosevelt’s judicial reform proposal? What does he mean when he calls it the “court-packing” plan? What sources does he cite in making his arguments, and why?

B. How does Glass’s understanding of the Constitution differ from that of Roosevelt (First Inaugural Address (1933); Acceptance Speech at the Democratic National Convention (1936); Second Inaugural Address (1937))? How does it compare to that of Herbert Hoover in Acceptance Speech at the Democratic National Convention (1937), or Al Smith in “Betrayal of the Democratic Party” (1936)?

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Message to Congress on Establishing Minimum Wages and Maximum Hours (May 24, 1937)

A. Why does he reject the notion that, because the economy is improving, “government should take a holiday”? Why does he think that this legislation will improve economic conditions? What does he mean when he says that government policy must be guided by “practical reason” rather than “barren formulae”?

B. How does this speech compare with Roosevelt’s address on the NIRA (“Fireside Chat” On the Purposes and Foundations of the Recovery Program (1933))? How does the Fair Labor Standards Act differ from that earlier piece of legislation? How might Roosevelt respond to the objections to this bill raised by Rep. Wade Kitchens in Speech on the Fair Labor Standards Act (1938)?

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Fireside Chat” on the Recession (April 14, 1938)

A. How, according to Roosevelt, is the current “recession” to be distinguished from the “Depression” of 1929-1932? Why does he draw such a distinction? What measures does he propose for addressing the situation? What does he fear will happen if government does not act to bring the country back on its course to recovery?

B. How does Roosevelt’s message compare with his first inaugural, similarly made during a time of economic crisis (First Inaugural Address (1933);)? Based on Consequences of the Proposed New Deal (1932); “This Challenge to Liberty” (1936), how do you think Herbert Hoover would respond to the claims Roosevelt makes in this speech?

Representative Wade Kitchens, Speech on the Fair Labor Standards Act (May 16, 1938)

A. Why does Kitchens believe that this proposal will hurt his home state? Why does he ultimately think it is dangerous for the country as a whole?

B. How does Kitchens’ critique of the Fair Labor Standards Act compare with the criticisms levied against the National Industrial Recovery Act in “The Right to Strike” (1933); Schechter Poultry Corp v. United States (1935); United States v. Butler (1936); and “Betrayal of the Democratic Party” (1936)?

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Fireside Chat” on “Purging” the Democratic Party (June 24, 1938)

A. What does Roosevelt cite as the most important legislative accomplishments of his second term so far? On what grounds does he suggest that the goals he sought to attain through his “court-packing” plan have largely been achieved? Why does he use the term “Copperheads” in reference to Democrats who have opposed his agenda? In what way does he intend to involve himself in the Democratic primaries, and why?

B. How do Radio Address on Judicial Reorganization (1937) and Speech on the Fair Labor Standards Act (1938) help us to understand why Roosevelt decided to pursue such a course? How might this speech have played into the hands of those such as Al Smith (“Betrayal of the Democratic Party” (1936)), Herbert Hoover (“This Challenge to Liberty” (1936)), Carter Glass (Radio Address on Judicial Reorganization (1937)) and Wade Kitchens (Speech on the Fair Labor Standards Act (1938)) who suggested that the New Deal was a menace to American liberties?

Anthony J. Badger, The New Deal: The Depression Years, 1933-1940 (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2002).

Albert Fried, FDR and His Enemies (New York: St. Martin’s, 1999).

Alonzo L. Hamby, Man of Destiny: FDR and the Making of the American Century (New York: Basic, 2015).

Glen Jeansonne, Herbert Hoover: A Life (New York: Berkley, 2016).

Ira Katznelson, Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time (New York: Liveright, 2014).

William E. Leuchtenberg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (New York: Harper Perennial, 2009).

Robert S. McElvaine, The Great Depression: America, 1929-1941 (New York: Times, 1993).

G. Edward White, The Constitution and the New Deal (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002).