The Story of the Constitutional Convention: as James Madison Wanted It Told

Americans seeking to understand how the founders developed our Constitutional framework of government have faced a problem deliberately created by the founders, who agreed on a rule of strict secrecy during their deliberations at the 1787 Constitutional Convention. Still, several delegates, conscious of the historical significance of the convention—and concerned about how its outcome would be interpreted—did keep private notes during the proceedings. James Madison set out to make as complete a record as possible, taking notes during each day’s debates and converting these each night into dialogues capturing the main points discussed that day. He held onto these notes until his retirement when he revised them for publication after his death. After this version was published by Henry Gilpin in 1840, 19th-century readers frequently consulted it as they debated the meaning of the Constitution. Yet, due to the work of later editors, 20th and 21st-century readers have been distanced from the account Madison completed in retirement.

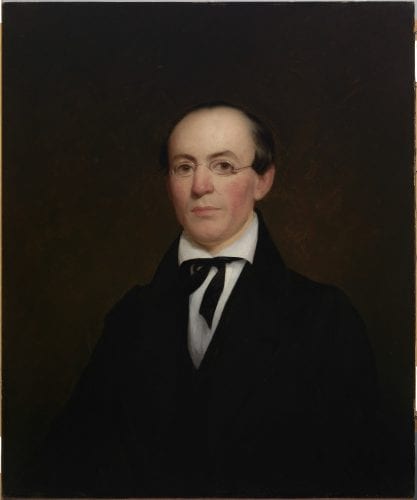

Professor Gordon Lloyd, a Senior Fellow at Ashbrook and Dockson Professor Emeritus at Pepperdine University, decided to restore the story of the convention as Madison wanted it to be told. Lloyd’s Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787, by James Madison, a Member, was published by Ashbrook press in 2014. It is now available at our online bookstore. We asked Lloyd to explain why he restored this version of the Debates.

1. In your introduction to the volume, you say, “Madison wasn’t a court-appointed stenographer.” His record of the debates does not capture every word spoken. It’s based on his daily diary of events, but it also reflects Madison’s mature thinking about what happened in 1787. Why did Madison return to his earlier account and revise it?

Madison was responding to an urgent public interest in what happened behind the closed doors of the convention. The Framers were dying, but the story had not yet been properly told. Madison wanted to tell the story, while choosing the time of its release. Because of a joint resolution of Congress calling for the records of the convention to be gathered and published, Madison had been asked in 1818 by John Quincy Adams, then Secretary of State, to turn over his notes. Madison had refused. He said that he did not want them to be used in public debates then ongoing over the powers of the judiciary and whether and how to limit slavery. He told Adams he did not want his account published until after his death.

Adams continued collecting all the information about the convention he could. He acquired the “journal” of the convention—a record kept by William Jackson, who was tasked to keep minutes of those who attended and of votes taken. Adams also acquired the notes of New York delegate Robert Yates and South Carolina delegate Charles Pinckney. He compiled and published these records as the Journal, Acts, and Proceedings of the Convention . . . which Formed the Constitution of the United States in 1819. (Later, in the mid-19th century, historian Jonathan Elliott combined these records, along with various letters commenting on the convention and the records of debates in several state ratifying conventions, and published them in a five-volume set.) When Adams’ compilation was published, Madison of course read through it. He used Jackson’s journal to check his own record of the dates and results of votes taken at the convention. Yates’ notes were incomplete since Yates left the convention in early July. Pinckney’s account appalled Madison. It altered the chronology of decisions, moving discussions that took place after a first draft of the Constitution was written to the discussions of June and early July. Madison wanted to give posterity a truer account.

He left his corrected manuscript to Dolley Madison, hoping she could arrange with Congress to have it printed. Dolley arranged for Madison’s Debates to be published with his other papers. Congress assigned the task to the State Department, where Henry Gilpin took charge, publishing Madison’s papers in 1840.

Although Madison said he did not want his account of the founding to become part of the political controversies of the early 19th century, that is what happened.

2. Really? Please explain.

In the 1842 case of Prigg v. Pennsylvania, the Pennsylvania attorney used Madison’s Debates to argue that a Pennsylvania law forbidding the removal of African Americans from the state in order to enslave them was within the will of the framers. This argument did not persuade the Court. Justice Story, writing the majority opinion, said that the Constitution made federal law superior to state law. A fugitive slave act passed by Congress in 1793 precluded the Pennsylvania law. The effect of this ruling was to discredit and silence Madison’s Debates.

Then William Lloyd Garrison and other abolitionists, who had already been disappointed in Madison for advocating only the gradual abolition of slavery, looked at Madison’s Debates and decided, by a logic that eludes me, that Madison’s account proved the framers wanted to perpetuate a slaveocracy. Declaring that the Constitution was corrupted by the slave interest, they conceded the evidence in Madison’s Debates to the slaveholders. After this, hardly anyone in the antebellum era used the Debates to prove either that the Constitution was a slaveholder’s document or that it wasn’t.

If you read through the Lincoln-Douglas Debates, and Chief Justice Roger Taney’s Dred Scott decision, you find not a single reference to Madison’s Debates. Taney made unsubstantiated claims about the founders’ views, using only state statutes as evidence. Lincoln may have read Madison’s account of the convention and concluded that discussing it would complicate his argument unnecessarily. He cited only official and legal documents—the Declaration, the Articles of Confederation, the Northwest Ordinance, and the Constitution itself.

3.Do the Debates show that the Founders did not mean to perpetuate slavery?

It depends on how you define “the founders.” In Madison’s account, the delegates from South Carolina stand out for their unified insistence that slavery be protected. Delegates from North Carolina and Georgia echo this insistence. But most of the other delegates express disapproval of slavery and unwillingness to encourage it.

The South Carolinians, because of their unity, wielded an influence at the Convention disproportionate to their small population. Theirs was the only delegation of which every member attended every debate, from the start of the Convention to its conclusion. In most organizations, those who attend every meeting acquire a certain status. This was certainly true of the South Carolinians, who would compromise on anything except slavery.

Abhorrence of slavery is voiced as early as June 6, when Madison makes a speech that in many ways is a forerunner of Federalist 10. He attributes the formation of factions to the different kinds of property citizens hold. Noting the power of property to shape opinions, he says,

We have seen the mere distinction of color made, in the most enlightened period of time, a ground of the most oppressive dominion ever exercised by man over man.

Already he anticipates the division that will rise in the Convention over what Southerners considered to be their “property” in human beings. In condemning slavery, Madison was joined by other delegates from Virginia—even though Virginia at the time held more slaves than any other state. Delegates from Pennsylvania, Maryland, Connecticut, and other states took the same position. They repeatedly voiced an expectation that slavery would eventually prove unprofitable and would cease. Gouverneur Morris, exasperated with Southern demands that abolition of the transatlantic slave trade be delayed for twenty years, suggested language that would have pointed out South Carolina, North Carolina, and Georgia as the reason for the delay. But the delegates decided to neither call out those states nor even mention the word slavery, lest they seem to legitimize the institution.

A worthwhile scholarly study might consider whether Madison’s Debates substantiate Lincoln’s claim that the founders intended to put slavery on the course of ultimate extinction.

4. Your edition of Madison’s Debates restores the account of the convention that Madison edited during his retirement, which had gone out of print. Why do you believe the work of Madison’s later years is more authoritative than his initial take on the debates, written as they happened?

I believe it’s as close as we can get to the real truth. Most modern historians disagree, privileging Madison’s earlier, unrevised account of the convention, which turned up in the files of the Bureau of Mines in the 1890s. The great scholar Max Farrand collected it with the other available records of the convention and published it in 1911, hoping to revive interest in the founders’ remarkable achievement.

For Farrand, Madison’s earlier version is more authentic, because it’s closer to the event. Yet Madison’s revised Debates give us the more complete story Madison intended.

5. Is Madison’s edited account historically more complete—or more reliable? Or would you call it philosophically closer to the truth? Or does the edited account, perhaps, capture a poetic truth?

Historically, it’s both more reliable and more complete, because all the other accounts are truncated. Yates leaves in early July, so he omits over half the story. Pinckney covers the whole convention but mixes up the chronology. Madison’s account correlates with Jackson’s record of the votes in his Journal, with the preserved copy of the Committee of Detail Report, and with comments Madison later made in letters to Jefferson and Washington.

But Madison’s account is also poetically more compelling. The other participants who kept notes didn’t put them together in the form of a dialogue. Madison shows us an unfolding conversation. He gives the speeches delegates made, using language that reveals their individual characters and responses to each other’s ideas. I go so far as to say that Madison intended to shape an American answer to Plato’s Republic—a dialogue we read as a poetic and philosophical account of a conversation that may or may not have actually occurred. If it did, we don’t know whether Socrates spoke primarily with Glaucon and Adeimantus, or whether the entire conversation unfolded over the course of one night. Plato was not a stenographer, either! We do know that in Plato’s account, Socrates leads the show, and answers the question, “What is the best regime?” with the prescription, “You’ve got to get rid of liberty.”

As for Madison’s dialogue, we know that it actually occurred over the course of 88 days, involving 55 different people, at least eight of whom make extremely important contributions. And Madison’s dialogue, unlike Socrates’, does not conclude with him the winner.

6. Since you see Madison’s Debates as a literary effort, you include in the back of your volume a summary of the convention as a “drama in four acts.”

Yes. How dare I use that framework, when Madison did not? I want to make Madison more available and readable by showing the implicit structure of his account.

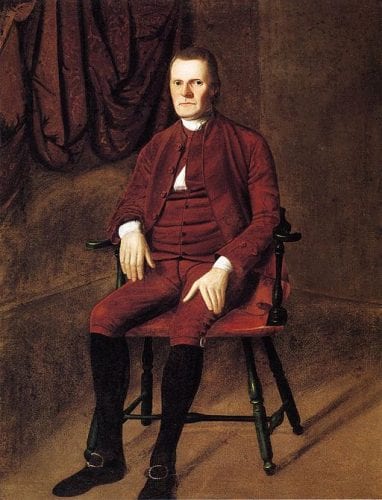

In the first act, young Edmund Randolph presents the Virginia Plan (largely authored by Madison) calling for proportional representation of the people in Congress. Delegates from smaller states object. Tensions build between those who want Congress to represent the people and those who want it to represent the states. Virginia amends its plan, only to see it countered by the New Jersey Plan, which provides only for the equal representation of states in Congress. South Carolina causes further division by insisting that its slaves be counted in any proportional representation plan.

The second act opens with this seemingly irresolvable three-dimensional conflict between popular representation, representation of states, and the age-old representation of wealth. The Convention appoints a committee chaired by Massachusetts delegate Elbridge Gerry to devise a solution. Independence Day comes, affording delegates a day off and time to reflect. Afterward, the Gerry Committee endorses a compromise that had been offered by Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut (and ably supported by Roger Sherman, also of Connecticut), allowing for proportional representation in the House and representation of states in the Senate. It also endorses the three-fifths compromise, giving the South more weight in the proportional representation plan for the House. The delegates study these proposals and pass them by slim margins. The crisis averted, the act closes with the creation of a Committee of Detail to draft a Constitution.

In the third act, the delegates examine this first draft, line by line. Another disagreement over slavery rises to the fore, this time over limiting the transatlantic slave trade. The Committee of Detail’s draft forbids ever limiting the trade. (That version of the Constitution, if adopted, would have been a slaveholder’s document.) Others, including Madison, wanted the trade to end immediately. Another committee is formed, and it proposes an end to the trade in the year 1800. When this is taken back to the convention, the South Carolinians push for another compromise, and the end date for the slave trade is set at 1808.

By the fourth act, most of the remaining decisions concern the presidency, a matter the delegates have repeatedly debated but not resolved. The delegates decide to elect the president through an Electoral College—a decision that, like the Connecticut compromise on representation, combines election by states with election by the people. Then they quickly settle the other issues. A committee is formed to write the final draft of the Constitution. After this is reviewed, all that remains is to sign it. Although three delegates who have faithfully attended all the debates—Randolph, Gerry, and Virginia delegate George Mason—now decide they cannot sign, all the others in attendance do sign. The mood of apprehension that prevailed throughout July and August is replaced by relief and happiness.

So, in Madison’s account of the creation of the best possible regime, he himself does not end up the presumed ruler, as Socrates does in Plato’s account. Yet anyone reading Plato realizes that his ideal regime will end as soon as the philosopher-king dies, or sooner—when the king is corrupted. Madison dares to hope that the regime resulting from his dialogue will last forever.

7. Was Madison in any way disappointed at the outcome?

Madison accepted it. Today we expect people to act on their convictions with unswerving fidelity, or we call them hypocrites. They had a different understanding of the relationship between thought and action at the time of the founding. They realized that personal convictions were one thing, but making those convictions reality required the consent of others. They also had a different understanding of compromise. The delegates to the Convention did not expect to reach consensus. They erected the framework of our government piece by piece, building it up from one compromise to the next.

Madison felt that the Constitution represented the deliberate sense of the delegates, who were the people’s representatives at the Convention. What’s important here is the word “deliberate.” It means that all the options were discussed and considered. A process of deliberation took place.

Madison is the last of the Founders to die. In part, that’s how he acquires the title, “Father of the Constitution.” He was influential, but I think he viewed the Constitution as the work of many, all of whom agreed to agree on a workable plan. If we want their framework to last another thirty or forty years, we must recognize their intent to create the best government possible for flawed human beings. They found what Plato did not: a space for human liberty. It was a space that later generations would work to enlarge, but it was a start.