Reconstruction

Before Union victory in the Civil War was assured, President Abraham Lincoln and his advisors were turning their attention to “reconstruction” in the South. It would be a time for reconciling the North and South, bringing the formerly rebellious Southern governments back into their proper relation with the union, and protecting the basic civil rights of freedmen, blacks, and Unionists in those Southern states. Each of these goals would be difficult in its own right. Reconstruction demanded them all, and that they all be done at the same time. It is no wonder, then, that Lincoln had been heard to say that Reconstruction posed the greatest question ever presented to practical statesmanship.

There are theoretical and practical reasons why Reconstruction proved to be too great a challenge for post-Civil War statesmen and politicians.

As a matter of theory, the American constitutional system carves out significant space for state sovereignty. The principles of the Declaration of Independence demand respect for government by consent of the governed and for the principles of human equality and the protection of natural rights.

Reconstruction revealed contradictions among these principles. State and local majorities in the defeated Southern states were uninterested in protecting the civil rights of freedmen and also uninterested in acknowledging human equality. What should be done under this circumstance? Should the national government limit the powers of state and local majorities? If so, would that be consistent with the consent of the governed? Should former rebels be considered part of the state and local majorities? If not, would that be consistent with the consent of the governed? Should the national government protect the rights of freedmen itself? Did the national government even have the capacity – constitutionally and practically – to protect freedmen in the states?

President Lincoln had to begin adopting policies about these issues while the Civil War still raged. Generally, Lincoln offered a generous amnesty to Southerners if they would quit the rebellion. He was unwilling to insist on very many abridgments of state sovereignty in Southern states that had been won back into the Union (See Lincoln). Most Republicans in Congress opposed Lincoln’s charitable policy toward Southern governments (See Wade-Davis Bill), yet Lincoln stood firm during the war with his generous amnesty and limited national oversight. He did gain passage of the 13th Amendment, which limited state sovereignty by abolishing slavery throughout the Union. Even in his “Last Public Address,” Lincoln deferred quite a bit to majorities in a reconstructed Louisiana government that did not extend the vote to freed slaves and did not provide education for freed slaves. We cannot know whether Lincoln would have persisted in this policy, since he was assassinated just days after his last public address.

President Andrew Johnson, who assumed the presidency after Lincoln‘s assassination, was a Tennessee Unionist. It was soon revealed that he opposed policies to protect and aid the freedmen. He allowed Southern governments to re-organize and regain their status in the Union with relative ease – demanding only that they adopt the 13th amendment, repudiate Confederate debt, and foreswear secession (See Johnson, Johnson, and Douglass). The governments that organized under Johnson’s plan did much to discredit his approach. Most famously, Confederate rebels won elective office. These rebels and their sympathizers led governments that adopted “black codes,” local regulations that appeared to be the re-introduction of slavery by another name. These laws generally reflected the state of Southern public opinion as reported to Congress by Carl Schurz, a Union general who went on a fact-finding tour of the South, in December 1865. Union feeling and respect for black civil rights, Schurz argued, were barely noticeable in the South; Johnson’s easy restoration of Southern states seemed to undermine the twin goals of recreating a healthy Union and winning genuine emancipation for blacks, Schurz argued.

Johnson’s evident satisfaction with his approach put him on a collision course with the Republicans, who demanded that a deeper change in Southern society and governance accompany the Union victory. Republicans looked for ways to require that Southern governments protect the civil rights of freedmen and provide equal protection of the laws. With these goals in mind, “Radical” Republicans in Congress first empowered the national government to protect civil rights, when states failed to do it, in the Civil Rights Act of 1866; they made these changes part of the constitutional fabric through the 14th Amendment that same year.

Then Congress did much to throw out Johnson’s restored Southern governments through the Reconstruction Acts of 1867. These Acts provided a more thorough process, directed by the military, for Southern states to regain their place in the Union. Self-government established through this more thoroughly supervised process, prominent Republicans hoped, would produce constitutions and working majorities in Southern states that would protect the civil rights of freedmen and loyal Union men. Loyalists would form the backbone of these governments, they hoped. Prominent Republicans learned that extending the vote to freedmen and prohibiting racial discrimination in voting had to be part of any post-Reconstruction Southern order that would protect civil rights and provide equal protection of the laws (See Sumner and Stevens).

The Democratic and Republican party platforms of 1868 reveal much about the Republicans’ pride in their accomplishments and the Democratic hope to undo them.

All Southern governments had been restored to the Union under the Reconstruction Acts by the first months of Ulysses S. Grant’s first term in 1869. Reconstruction appeared to be over. Yet all was not well under these reconstructed Southern governments. Reports from throughout the South suggested that loyal Union men, blacks, and freed slaves were subject to violence and threats of violence, if they participated in politics or asserted their civil rights (See Sumner, “Executive Documents on State of the Freedmen,” and Grant). Few Southern whites would do much to protect blacks or Republicans. The processes under the Reconstruction Acts were insufficient to protect the right to vote from private intimidation and governmental inaction, if whites controlled local government and working majorities arose after elections fraught with intimidation and violence.

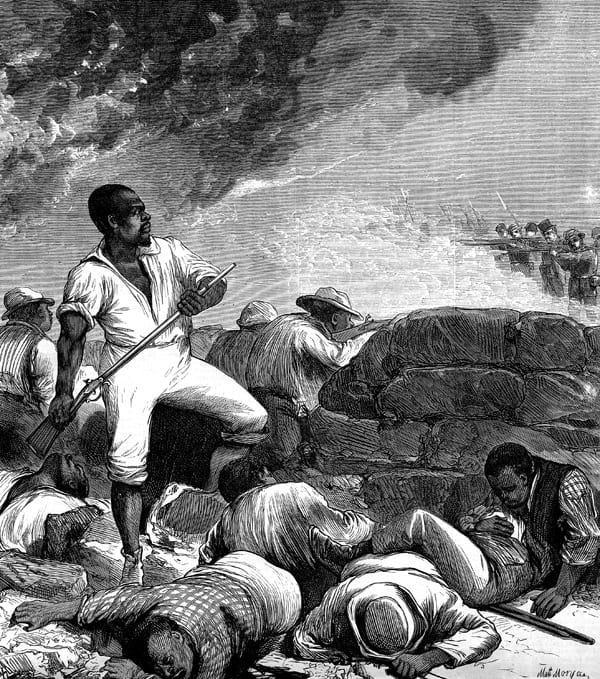

In light of this evidence, Republicans in Congress, with Grant’s blessing, passed a series of bills known as Enforcement Acts, or the Ku Klux Klan Acts, in 1870 and 1871. This marked an additional phase in Reconstruction. These bills made actions that hindered the right to vote or that intimidated people against exercising their civil rights, among many other things, into federal crimes. With such federal protection, it was hoped, elections in the Southern states could be fair representations of the state population. Such federal action seemed necessary to secure the consent of all the governed. Grant especially appealed to the citizens of the South to turn on the Ku Klux Klan and other private organizations that hindered their fellow citizens from voting. In some cases, Grant even brought federal troops into Southern states to provide protection for black citizens. A low-level civil war seemed to be breaking out in various parts of the South, and military protection seemed necessary for freedmen to enjoy their civil rights and voting rights (See Colfax Massacre Reports).

It was very difficult to maintain sufficient support to keep up such forceful actions. Many in the North, including now Senator Carl Schurz, who had earlier supported vigorous national action, begged for a broad amnesty so that former rebels could hold office (See Schurz). Schurz’s efforts in this respect were part of a broader effort within the Republican Party called Liberal Republicanism to end national efforts to reconstruct the South. A series of Supreme Court cases during Grant’s second term offered narrow conceptions of national power under the 14th and 15th amendments. The Slaughterhouse Cases and United States v. Cruikshank undermined the national government’s ability to protect freedmen and loyal Union men in the South.

Waning Northern support and the sheer difficulty of the task led even the Republican Party, ultimately, to limit its efforts to protect civil and voting rights in the South. With the election of Rutherford B. Hayes to the presidency in 1876, the Republicans ended military oversight in the South. Republicans, who had fought for the Union, done much in law to protect civil rights, and done not a little to improve the lives of freedmen in the South, ended up – unwittingly, perhaps – allowing a return to white home rule in the South during Hayes’s Presidency. Some observers, including the great abolitionist Frederick Douglass, even wondered whether the Union soldiers slain in the Civil War had died in vain and whether the country still existed half slave and half free.

No task was more difficult than Reconstruction. Perhaps more radical efforts (such as land confiscation and redistribution) to punish rebels could have changed the South (See Stevens). Perhaps Lincoln, had he lived, would have worked out a more acceptable accommodation protecting the freedmen while sewing up the Union. Perhaps if Lincoln had not selected Andrew Johnson to be his Vice President, a more responsible and committed reformer would have brought about a better result. No one had more political skill and upright intention than Lincoln, and no one had less of each than Johnson.

Republicans tried several times to “start over” on Reconstruction, but the South was no blank slate and starting over was not a realistic option. Perhaps only time could bring about the changes necessary to reconcile Southern home rule and protection for freedmen, as Lincoln himself seemed to suggest in his first statement on these matters.

A Note on Usage:

To promote readability, we have in most instances modernized spelling and in some instances punctuation. Occasionally, we have inserted italicized text, enclosed in brackets, to bridge gaps in syntax occurring due to apparent errors or illegibility in the source documents, or to briefly explain long passages of text left out of our excerpts. With regard to capitalization, however, we have in most cases allowed usage to stand where it is internally consistent, even when varying from today’s usage, since authors writing in the aftermath of the Civil War may signal their attitudes toward the balance between state and federal power through capitalization.

Presidential Proclamations

President Abraham Lincoln, Proclamation on Amnesty and Reconstruction, December 8, 1863

Wade-Davis Bill and President Abraham Lincoln’s Pocket Veto Proclamation, July 2 and 8, 1864

President Andrew Johnson, Proclamation on Reorganizing Constitutional Government in Mississippi, June 13, 1865

President Ulysses S. Grant, Proclamation on Enforcement of the 14th Amendment, May 3, 1871

Constitutional Amendments

Wade-Davis Bill and President Abraham Lincoln’s Pocket Veto Proclamation, July 2 and 8, 1864

Congressional Debate on the 14th Amendment, February – May, 1866

The 15th Amendment, February 2, 1870

National Laws on Reconstruction

The 13th Amendment to the Constitution, December 18, 1865

An Act to protect all Persons in the United States in their Civil Rights, and furnish the Means of their Vindication, April 9, 1866

Reconstruction Acts, March 2 and 23, and July 19, 1867

The Enforcement Acts, 1870, 1871

Supreme Court Cases

Associate Justices Samuel Miller and Stephen Field, The Slaughterhouse Cases, The United States Supreme Court, April 14, 1873

Chief Justice Morrison Waite, United States v. Cruikshank, The United States Supreme Court, March 27, 1876

Reports on Conditions in the South

Black Codes of Mississippi, October – December, 1865

Carl Schurz, Report on the Condition of South, December 19, 1865

Frederick Douglass, Reply of the Colored Delegation to the President, February 7, 1866

Executive Documents on State of the Freedmen, November 20, 1868

Charlotte Fowler’s Testimony to Sub-Committee on Reconstruction in Spartanburg, South Carolina, July 6, 1871

Colfax Massacre Reports, U.S. Senate and the Committee of 70, 1874 and 1875

Amnesty

President Abraham Lincoln to General Nathaniel Banks, August 5, 1863

President Abraham Lincoln, Proclamation on Amnesty and Reconstruction, December 8, 1863

Wade-Davis Bill and President Abraham Lincoln’s Pocket Veto Proclamation, July 2 and 8, 1864

Richard Henry Dana, “Grasp of War,” June 21, 1865

President Andrew Johnson, First Annual Message, December 4, 1865

Alexander Stephens, Address before the General Assembly of the State of Georgia, February 22, 1866

Charles Sumner, “The One Man Power vs. Congress!” October 2, 1866

Thaddeus Stevens, Speech on Reconstruction, January 3, 1867

Thaddeus Stevens, “Damages to Loyal Men,” March 19, 1867

Senator Carl Schurz, “Plea for Amnesty,” January 30, 1872

President Rutherford B. Hayes, Inaugural Address, March 5, 1877

Reconstruction and Readmittance of Southern Governments

President Abraham Lincoln, Proclamation on Amnesty and Reconstruction, December 8, 1863

Wade-Davis Bill and President Abraham Lincoln’s Pocket Veto Proclamation, July 2 and 8, 1864

President Abraham Lincoln’s Last Public Address, April 11, 1865

President Andrew Johnson, Proclamation on Reorganizing Constitutional Government in Mississippi, June 13, 1865

President Andrew Johnson, First Annual Message, December 4, 1865

Carl Schurz, Report on the Condition of South, December 19, 1865

Alexander Stephens, Address before the General Assembly of the State of Georgia, February 22, 1866

Charles Sumner, “The One Man Power vs. Congress!” October 2, 1866

Thaddeus Stevens, Speech on Reconstruction, January 3, 1867

Reconstruction Acts, March 2 and 23, and July 19, 1867

President Andrew Johnson, Veto of the First Reconstruction Act, March 2, 1867

The Enforcement Acts, 1870, 1871

Civil Rights and Protection of Freedmen and Loyalists

Carl Schurz, Report on the Condition of South, December 19, 1865

Frederick Douglass, Reply of the Colored Delegation to the President, February 7, 1866

Alexander Stephens, Address before the General Assembly of the State of Georgia, February 22, 1866

An Act to protect all Persons in the United States in their Civil Rights, and furnish the Means of their Vindication, April 9, 1866

Charles Sumner, “The One Man Power vs. Congress!” October 2, 1866

Thaddeus Stevens, Speech on Reconstruction, January 3, 1867

Thaddeus Stevens, “Damages to Loyal Men,” March 19, 1867

The Enforcement Acts, 1870, 1871

President Ulysses S. Grant, Proclamation on Enforcement of the 14th Amendment, May 3, 1871

Associate Justices Samuel Miller and Stephen Field, The Slaughterhouse Cases, The United States Supreme Court, April 14, 1873

Chief Justice Morrison Waite, United States v. Cruikshank, The United States Supreme Court, March 27, 1876

Frederick Douglas, “The United States Cannot Remain Half-Slave and Half-Free,” April 16, 1883

Speeches

President Andrew Johnson, First Annual Message, December 4, 1865

Alexander Stephens, Address before the General Assembly of the State of Georgia, February 22, 1866

Charles Sumner, “The One Man Power vs. Congress!” October 2, 1866

Thaddeus Stevens, Speech on Reconstruction, January 3, 1867

Thaddeus Stevens, “Damages to Loyal Men,” March 19, 1867

Senator Carl Schurz, “Plea for Amnesty,” January 30, 1872

Frederick Douglas, “The United States Cannot Remain Half-Slave and Half-Free,” April 16, 1883

For each of the Documents in this collection, we suggest below in section A questions relevant for that document alone and in Section B questions that require comparison between documents.

1. President Abraham Lincoln to General Nathaniel Banks (August 1863)

A. What policies does President Lincoln want the new constitution of Louisiana to embody? What powers does President Lincoln think he has? On what kinds of issues does he merely suggest what should be done? Why does President Lincoln think himself empowered only to suggest, not to order, that Louisiana adopt certain constitutional provisions?

B. Compare the tone and orders of President Lincoln in this letter to General Nathaniel Banks with the tone and orders found in the “Wade-Davis Bill and President Lincoln’s Pocket Veto” and “Reconstruction Acts” where variations of Radical Republican policies are pursued and when President Andrew Johnson vetoes Radical bills.

2. President Abraham Lincoln, Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction (December 8, 1863)

A. How can people receive amnesty under President Lincoln’s Proclamation? Who could in good conscience take the oath that President Lincoln suggests? Who must ask for special pardon under the Proclamation? Does this seem to be a large group of people? Describe the process whereby states will come back into the union under the Proclamation.

B. Compare the people allowed to vote for the states’ new constitutional convention under President Lincoln’s Proclamation with those able to participate under the Wade-Davis Bill. Compare the process of restoration under President Lincoln’s Proclamation with the process of restoration under the Wade-Davis Bill and the Reconstruction Acts. What accounts for the differences? What different visions of Reconstruction are in each of the proposals? What would be the result of each process?

3. Wade-Davis Bill and President Lincoln’s Pocket Veto Proclamation (July 1864)

A. What is the process for reconstruction under the Wade-Davis Bill? Describe it step-by-step from the creation of the provisional government to the seating of the states’ congressional delegations. What standards must state constitutional conventions adhere to in order to win approval? What threats does the Wade-Davis Bill imagine will continue to plague the Southern states? How does it propose to deal with the threat? How will states be governed until they are fully reconstructed and allowed back into the Union? Why does President Lincoln veto the Bill? What is his chief complaint against it?

B. Compare the people allowed to vote for the states’ new constitutional convention under President Lincoln’s Proclamation with those able to participate under the Wade-Davis Bill. Compare the process of restoration under the Wade-Davis Bill with the process under President Lincoln’s Proclamation and the process under the Reconstruction Acts. What accounts for the differences? How do the differences reflect different ideas about the American Union and the goals of the Civil War? How might history have been different had President Lincoln signed the Wade-Davis Bill?

A. How does the 13th Amendment change relations between the state and national governments? Imagine how the 13th Amendment would be enforced if a state tried to institute slavery within its borders.

B. Compare the restructuring of national and state relations under the 13th Amendment with the restructuring under the 14th Amendment and the 15th Amendment.

5. President Abraham Lincoln’s Last Public Address (April 11, 1865)

A. What defects does President Lincoln identify in the Louisiana constitution? What does he suggest be done about those defects? What is the broader theory of reconstruction within his statement?

B. How does President Lincoln’s policy as stated in his “Last Public Address” differ from the Radical policies as found in the Reconstruction Acts? How does it compare with the theory implicit in the speeches of Representative Thaddeus Stevens (See “Speech on Reconstruction” and “Damages to Loyal Men“)? What are the pitfalls of each policy?

A. What standards would President Johnson hold new Southern states to? What process does he lay out for the restoration of Southern government to the union?

B. Compare the process of restoration under President Johnson’s Proclamation with the Wade-Davis Bill, with the process under President Lincoln’s Proclamation and with the process under the Reconstruction Acts. What accounts for the differences? How do the differences reflect different ideas about the American Union and the goals of the Civil War? Rank the processes from the easiest to satisfy to the most difficult to satisfy.

7. Richard Henry Dana, “Grasp of War” (June 21, 1865)

A. What kind of power does Dana think the Union has over the defeated South? What should it use its power to accomplish? What is secession in Dana’s view? What are the limits, if any, of the Union’s power in Dana’s view? How would Reconstruction end in his view?

B. How does Dana’s view of the war compare with President Andrew Johnson’s view (See “First Annual Address” and “Veto of the First Reconstruction Act“) and President Lincoln’s view?

8. Black Codes of Mississippi (October – December, 1865)

A. Describe the various ways that freedom for freed slaves is compromised under the black codes of Mississippi. How is life under the black codes different from slavery?

B. Would the 13th Amendment help to limit the powers of the state to pass black codes? Under what reading of the 13th Amendment would it be of help to freed slaves? What vision of federal power would be necessary to prevent states from passing and enforcing Black Codes (consider “An Act to Protect All Persons in the United States in Their Civil Rights, and Furnish the Means of their Vindication,” “Congressional Debate on the 14th Amendment,” and “The Enforcement Acts“)? What might explain why black codes arose in these states (consider “Plea for Amnesty“)?

9. President Andrew Johnson, First Annual Address (December 4, 1865)

A. Why did President Johnson think that it was wrong and imprudent to impose military governments on the South? Why does President Johnson think that all acts of secession are “null and void”? What is the significance of that idea? In what ways has the national authority come to be operating in the South? What is the national government doing? By what authority? What is President Johnson’s reconstruction policy? What are the risks associated with President Johnson’s policy? What policy to promote the welfare of freedmen does President Johnson offer? What standards would he hold the new Southern governments to? What, in President Johnson’s view, was wrong with slavery?

B. How does President Johnson’s understanding of secession differ from Richard Henry Dana’s vision of secession (as articulated by Dana)? What is the significance of this difference? How does the report of Carl Schurz account for the risks associated with President Johnson’s policy? How might those risks be mitigated?

10. Carl Schurz, Report on the Condition of the South (December 19, 1865)

A. According to Schurz, what are the attitudes of Southerners toward Union men, the Union, and freedmen? What kind of evidence would convince you that Schurz had accurately described Southern opinion on these matters?

B. If you were a member of the U.S. Congress and had just heard President Johnson’s First Annual Address, how would you compare and contrast Johnson’s view of the South to Schurz’s? If you believed Schurz, what actions would you consider taking? How does Schurz’s description of the South compare to the descriptions in the “Black Codes of Mississippi,” “Executive Documents on State of the Freedmen,” “Charlotte Fowler’s Testimony to Sub-Committee on Reconstruction in Spartanburg, South Carolina,” and the “Colfax Massacre Reports“?

11. Frederick Douglass, Reply of the Colored Delegation to the President (February 7, 1866)

A. Why did President Johnson think that a party uniting poor white Southerners and freedmen would be impossible? What does Frederick Douglass think the foundation for a permanent peace among whites and blacks in the South must be? How did Douglass respond to President Johnson’s views? Why does Douglass oppose colonization? What ultimately is Douglass’s vision for a multi-racial American South? What are the obstacles to that vision?

B. Does this document show President Johnson’s actual Reconstruction policy to correspond to or differ from the policy he presented in this first annual address to Congress? Does the argument Douglass makes about the foundations for a permanent peace support a position of general amnesty for the Southerners as put forward later by Carl Schurz? How does Douglass’s position compare with the position of President Lincoln in his letter to General Nathaniel Banks?

A. What moral virtues are necessary for all Americans to adopt, in Stephens’s view? Why? Why does Stephens think that President Johnson’s policy of restoration offers the best hope for peace within the Union? What policies does Stephens recommend Georgia adopt for freedmen? What ultimately is Stephens’s vision for a multi-racial American South? What are the obstacles to that vision?

B. How do Stephens’s recommendations compare with the recommendations of President Lincoln (“Letter to General Nathaniel Banks” and “Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction“) and President Johnson? What in Stephens’s view was the status of secession – were the states out of the Union or not? What implications do Stephens’s views have for his recommended national and state policies?

A. What rights does the Civil Rights Act seek to protect? What actions does the Civil Rights Act make illegal? What actions of state governments in particular does it make illegal? What is the process whereby the national government will seek to protect these rights? If someone’s rights are violated, what happens? What institutions will be involved in protecting these rights? What kinds of conspiracies is the Civil Rights Act aimed to ferret out and prosecute? How will the act accomplish this?

B. In what ways does the Civil Rights Act embody or contradict President Johnson’s vision of the Union? In what ways does it embody or contradict the vision of Union announced in Dana’s speech, the ideas of Senator Charles Sumner or the speech of Representative Thaddeus Stevens? What difficulties can you imagine confronted those enforcing the Civil Rights Act, given the situation as described by Carl Schurz in his Report on the Condition of the South or the testimony later gathered about the activities of the Ku Klux Klan (See “Charlotte Fowler’s Testimony to Sub-Committee on Reconstruction in Spartanburg, South Carolina” and the “Colfax Massacre Reports“)? Did the Civil Rights Act have a solid constitutional justification before the 14th Amendment? How are the Enforcement Acts related to the Civil Rights Bill?

14. Congressional Debate on the 14th Amendment, (February – May, 1866)

A. What standards does the 14th Amendment hold states to? What incentives does Section 2 of the 14th Amendment put in place for encouraging states to grant the vote to the freedmen and others? Who does the 14th Amendment seek to prohibit from holding national office? Why? In what ways can Congress enforce the 14th Amendment? What were the prominent arguments in favor of the 14th Amendment? Why was debate about the 14th Amendment postponed at the end of February 1866? What changes to the amendment were made before its passage? What is the significance of those changes? How is the vision of federalism different in the first draft of the amendment compared to the second draft?

B. How might states violate the 14th Amendment? Consider in this light the evidence from Schurz, “Charlotte Fowler’s Testimony to Sub-Committee on Reconstruction in Spartanburg, South Carolina” and the “Colfax Massacre Reports.” How might the courts be involved in enforcing the 14th Amendment, especially given the role assigned to the courts by the Civil Rights Bill? If you are a citizen of a state and the state does not investigate a crime against you because you are black, while it does investigate the same crime when it is committed against whites, would you be able to take the state to federal court even without other enabling legislation (such as the Civil Rights Act or the Enforcement Acts?

15. Charles Sumner, “The One Man Power vs. Congress!” (January 3, 1867)

A. What is Senator Sumner’s critique of President Johnson? What extensions of federal policy does Senator Sumner envision? What would he like to do, and what would he like to undo? What are his reasons for departing from what has been done? What role of the national government does he envision during Reconstruction? Why does he think Congress should take the lead in Reconstruction?

B. How does Senator Sumner go beyond the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the 14th Amendment? How does Senator Sumner’s treatment of the political situation in 1867 compare with Representative Thaddeus Stevens’s treatment (see “Speech on Reconstruction” and “Damages to Loyal Men“)?

16. Thaddeus Stevens, Speech on Reconstruction (January 3, 1867)

A. What extensions of federal policy does Representative Stevens envision? What would he like to do? What would he like to undo? What are his reasons for departing from what had been done? What role of the national government does he envision in Reconstruction?

B. How does Stevens’s vision of the national government compare to Schurz’s in his “Plea for Amnesty”? What does Stevens think the 14th Amendment empowers the national government to do? Does he think that the 14th Amendment is enough? Why? Why not? Would, in your view, Stevens have made the same speech after The Slaughterhouse Cases and United States v. Cruikshank?

17. Reconstruction Acts (March 2, 1867, March 23, 1867, and July 19, 1867)

A. What role would the military play under these acts? How would laws be made and how would violations of the law be judged? What does the Reconstruction Act have to say about the legality of the governments created under President Johnson’s restoration policy? Describe the process by which states would make new constitutions under the Reconstruction Acts. What standards would states be held to in making these constitutions? How would Congress and the President be involved in acknowledging the reconstructed states? How can the states so affected get the military to leave their states? Under what circumstances might Section 5 of the March 23, 1867 act be used to deny the legality of a state’s convention and vote?

B. How does the oath of the March 23, 1867 act compare to the oath that President Lincoln penned in his Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction? Generally speaking, how does the process of readmitting states in the Reconstruction Acts compare with the process President Lincoln imagines, with the Wade-Davis Bill, and with President Johnson’s approach (see “Proclamation on Reorganizing Constitutional Government in Mississippi” and “First Annual Address“)?

18. President Andrew Johnson, Veto of the First Reconstruction Act (March 2, 1867)

A. What arguments does President Johnson make against military rule in the South? How well are the Southerners re-integrated into the Union at this point, according to President Johnson? What according to President Johnson is the purpose of the Reconstruction Act? Why does he think that purpose is outside the power of the Constitution? Why, in his view, might it be outside the Declaration and its principles as well?

B. How do you think that the Republicans who passed the Reconstruction Acts would respond to the arguments made by President Johnson in his veto message? How might President Lincoln respond to them in light of his last public address?

19. Thaddeus Stevens, “Damages to Loyal Men” (March 19, 1867)

A. Who are the loyal men, according to Representative Stevens? What damages have been done to them? How can those loyal men be rewarded for their loyalty? What must the national government do to so reward them? How might the redistribution of land assist in the restructuring of the South? How far would Representative Stevens be willing to go in redistributing land? What obstacles might there have been to Stevens’ approach as outlined in this speech? What national support would have been necessary to make the Stevens’ plan work?

B. Placing Representative Stevens’ speech in context, how does his approach differ from the approach of the Reconstruction Acts and the approach of President Johnson? How does his approach to land redistribution compare with the civil rights approach initiated in 1866 (see “An Act to Protect All Persons in the United States in Their Civil Rights, and Furnish the Means of their Vindication” and “Congressional Debate on the 14th Amendment“) and the voting approach initiated in 1870 (see “The 15th Amendment” and “The Enforcement Acts“)? Do you think that his approach would have worked better than the other two approaches? What benefits and costs might this approach have had over the others?

20. Democratic and Republican Party Platforms of 1868 (May 20, 1868 and July 4, 1868)

A. What goals do the Republicans embrace for Reconstruction? How do their goals compare to the Democrats’ goals? What things are present in the Republicans’ goals that are absent in the Democrats’ goals? What things are absent in the Republicans’ goals but present in the Democrats’ goals? How do the two parties judge President Johnson’s tenure in office? What picture do the respective parties paint of the South as eventually reconstructed? What is the role of blacks in that new order each party envisions?

B. To what extent is the Republican Party platform a continuation of the Reconstruction Acts? To what extent is it an extension of Lincoln’s policy of Amnesty and Reconstruction? To what extent is the Democratic Party’s platform a continuation of President Johnson’s approach (see “Proclamation on Reorganizing Constitutional Government in Mississippi,” “First Annual Address,” and “Veto of the First Reconstruction Act“)? How would each platform deal with problems that might arise from violent private organizations, operating without interference from the state, such as the Ku Klux Klan?

21. Executive Documents on the State of the Freedmen (November 20, 1868)

A. What does the Secretary of War report as happening in the sections of Texas under investigation? Are the goals of Reconstruction policy being achieved? Why or why not?

B. Have the Civil Rights and Reconstruction Acts been successful up to this point? If not, what would be necessary to make them successful? How does Carl Schurz’s description of the South compare to the descriptions in “Black Codes of Mississippi,” “Report on the Condition of the South,” “Charlotte Fowler’s Testimony to Sub-Committee on Reconstruction in Spartanburg, South Carolina” and the “Colfax Massacre Reports“? What has changed in the South since Schurz made his report? How does the reality described here compare with the reality that gave rise to the Enforcement Acts?

22. The 15th Amendment (February 26, 1869 [passed] and February 2, 1870 [ratified])

A. How does the 15th Amendment change relations between the national and state governments? How might Congress use its law-making powers to enforce the provisions of the 15th Amendment? How is the approach in the 15th Amendment different from granting the national government the power to insist upon uniform voting requirements in the states? How might states circumvent the 15th Amendment in an attempt to prevent bs from voting?

B. How does the 15th Amendment compare to the 14th Amendment on the issue of protecting rights? In what ways does the 15th Amendment enforce itself? In what ways does it require Congressional action for its enforcement (see “Enforcement Acts“)? What hopes did Republicans hang on granting the vote to blacks nationwide (see Sumner and Stevens)? Why did President Johnson want to keep the question of the vote at the state level? Who had the stronger argument – the Republicans, or President Johnson? Why? What long-term implications would the 15th Amendment have for the nature of the national government?

23. The Enforcement Acts (March 30, 1870 and April 20, 1871)

A. What actions are made illegal under the Acts? What powers are given to the national government to enforce the acts? What kinds of actions would prompt the national government into action under these acts?

B. What kinds of threats do states and state actions and inaction pose to the execution of the 15th Amendment? How does this Enforcement Act compare to the Civil Rights Act? Which rights does each focus on, and what processes does each set up to protect these rights? Which act is more extensive in its attempt to protect freedmen? Which abridges state power the most? How might the different emphases and mechanisms for enforcement be explained by events that happened between the passage of the Civil Rights Bill of 1866 and the Enforcement Acts of 1870 and 1871?

24. President Ulysses S. Grant, Proclamation on Enforcement of the 14th Amendment (May 3, 1871)

A. What is the substance of President Grant’s Proclamation concerning the Enforcement Acts? Why do you think that President Grant issued this Proclamation?

B. In what ways does President Grant’s Proclamation amplify the First and Second Enforcement Acts?

A. What do we learn about Southern society after the war from Charlotte Fowler’s testimony? Who would be threatened by the Ku Klux Klan? What purposes did their violence serve? Why was Wallace Fowler killed?

B. How does the portrait of Southern society presented in the testimony compare with that in Carl Schurz’s Report on the Condition of the South and in the Executive Documents on the State of the Freedmen? What kinds of laws would be necessary to protect people such as Wallace and Charlotte Fowler? Had such laws been passed by Congress? What does this tell us about Reconstruction?

26. Senator Carl Schurz, “Plea for Amnesty” (January 30, 1872)

A. What are Senator Schurz’s arguments for amnesty? How far should that amnesty extend? What benefits does he expect to flow from granting amnesty? What in his view are the reasons white Southerners perpetrate violence against Southern blacks?

B. How do Schurz’s views in his “Plea for Amnesty” compare and contrast with his views in his Report on the Condition of the South? What has changed? What other speeches and views present arguments similar to Schurz’s? Do you think his “Plea” or Representative Thaddeus Stevens’s “Damages” presents a surer basis for peace? Should the Southerners be treated like vanquished foes or fellow citizens? Is there any tenable ground between these two positions?

A. What, according to the Court, were the purposes of the Civil War Amendments (see

“The 13th Amendment to the Constitution,” “Congressional Debate on the 14th Amendment,” and “The 15th Amendment“)? What are the “privileges and immunities” of United States citizenship? What rights come with U.S. citizenship? What argument does the Court make for this understanding of U.S. citizenship? Would you characterize it as a broad or a narrow understanding of U.S. citizenship? How does Justice Field’s dissenting opinion differ from the Court’s opinion? What rights does Justice Field think come with U.S. citizenship? What is his reading of these amendments?

B. Would the Supreme Court’s reasoning in the Slaughterhouse Cases support the Civil Rights Bill of 1866? Do the deliberations on the 14th Amendment support the Court’s reading of the 14th Amendment or that of Justice Field?

28. Colfax Massacre Reports, U.S. Senate and the Committee of 70, 1874 and 1875

A. What happened at Colfax? How does the account offered by Congress differ from the account offered by the Committee of Seventy? What explains the difference? What do the two accounts of the Colfax Massacre tell us about white Southerners’ views of the freedmen?

B. What does this massacre tell us about the need for the Enforcement Acts and the Civil Rights Bill? How does it complement or contradict the Executive Documents on the State of the Freedmen from December 1868? What could the national government do to prevent such massacres? What obstacles existed to effective national action on such matters?

A. What powers reside with the states and what powers with the national government according to United States v. Cruikshank? How would that division of power between the levels of government foster the investigation of crimes such as the Colfax Massacre? What does United States v. Cruikshank do to the Enforcement Acts?

B. Does the vision of national and state power in United States v. Cruikshank resemble or contradict the arguments made for the 14th Amendment? Would the Civil Rights Act of 1866 survive the analysis of United States v. Cruikshank and the Slaughterhouse Cases ? What reconstruction powers are left in the national government after United States v. Cruikshank?

30. President Rutherford B. Hayes, Inaugural Address (March 5, 1877)

A. What federal obligations does President Hayes emphasize? What promises does he extend for the protection of freedmen? What measures will he pursue to reconcile Southerners to the new Union? What problems might arise from his approach?

B. How do the Slaughterhouse Cases and United States v. Cruikshank shape President Hayes’s policy? Which President does Hayes most seem to resemble (compare Lincoln, Johnson, Johnson, and Grant)? Why do you think he adopts the policy he adopts?

31. Frederick Douglass, “The United States Cannot Remain Half-Slave and Half-Free” (April 16, 1883)

A. What are the grounds for pessimism about race relations, according to Douglass? Why are the grounds for optimism more compelling in his view?

B. How does Douglass’s account of what has been accomplished in Reconstruction compare with Hayes’s treatment his Inaugural Address? What specific events from the Reconstruction Era support Douglass’s optimism? Which support his pessimism?

Donald, David Herbert. Liberty and Union. Lexington, MA: D.C Heath and Company, 1978.

Guelzo, Allen C. Reconstruction: A Concise History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Krug, Mark M. Lyman Trumbull: Conservative Radical. New York: A. S Barnes, 1965.

Schurz, Carl. The Autobiography of Carl Schurz. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908.

Stampp, Kenneth M. The Era of Reconstruction, 1865-1877. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1965.

Simpson, Brooks D. The Reconstruction Presidents. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1998.

White, Ronald C. American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant. New York: Random House, 2016.