Introduction

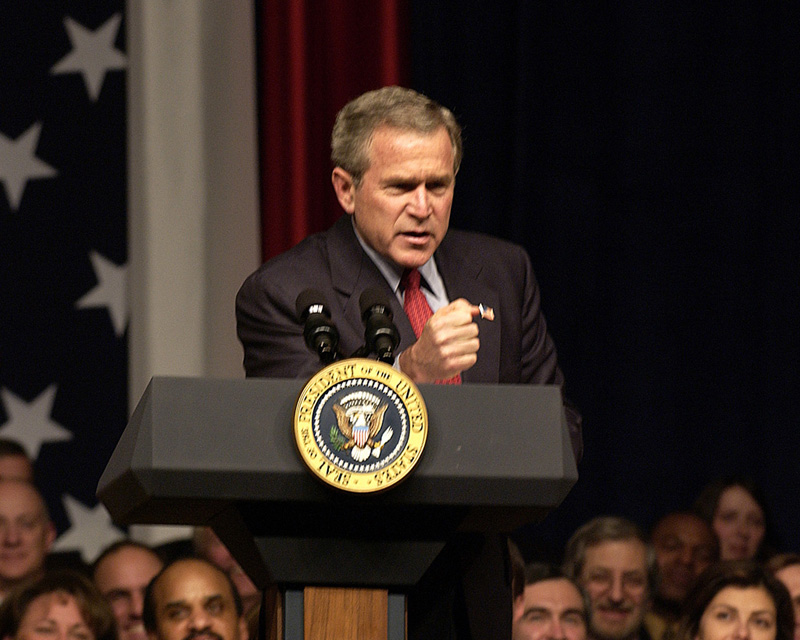

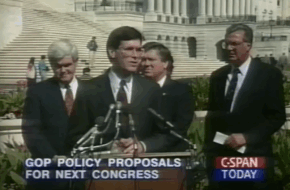

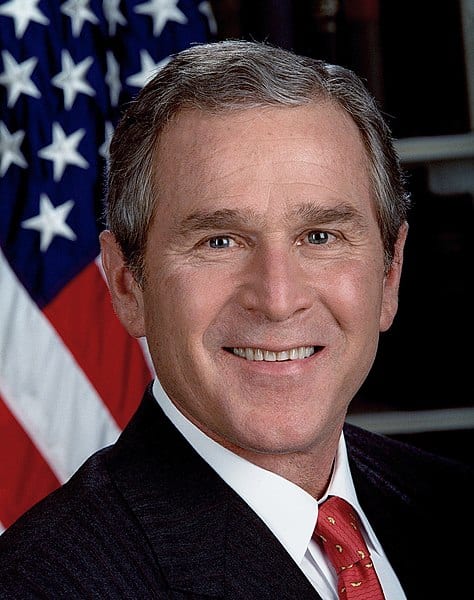

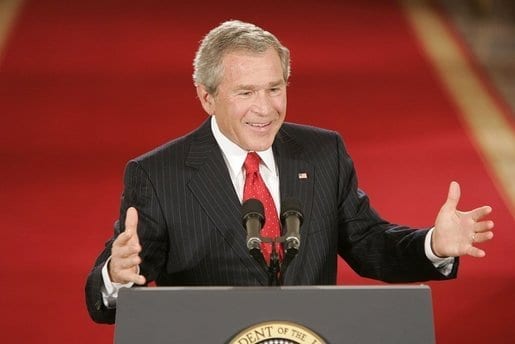

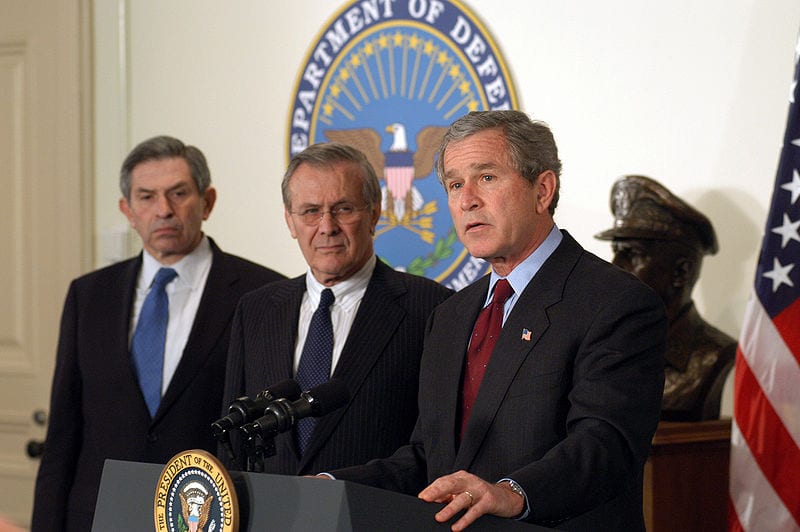

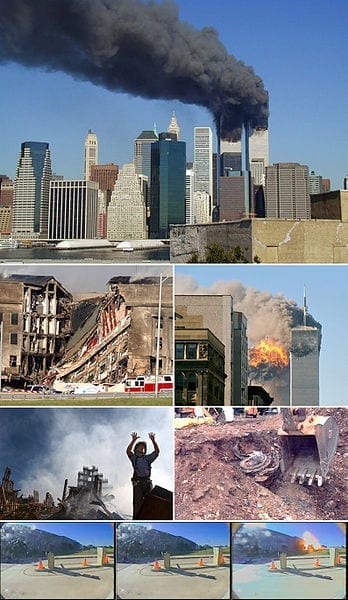

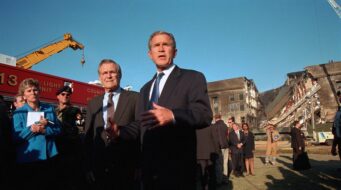

The Detainee Treatment Act of 2005 prohibited inhumane treatment of enemy combatants and required military interrogations to be performed according to the U.S. Army Field Manual for Human Intelligence Collector Operations. Known as the “McCain Amendment” after Senator John McCain (1936–2018), who had been tortured when held as a prisoner during the Vietnam War, the amendment was designed to halt the use of torture on detainees during the Bush administration’s War on Terror. President Bush signed the act into law, but concurrently with his approval of the legislation the president also included a signing statement that appeared to call into question Congress’ authority to impose such limitations on the executive. This document includes the relevant provisions of the Detainee Treatment Act along with President Bush’s signing statement.

Signing statements are official pronouncements issued by the president when signing a bill into law. Unlike a veto, a signing statement is not part of the legislative process as set forth in the Constitution, and it has no legal effect. While the history of signing statements dates to the early nineteenth century, the practice has become the source of significant controversy in the modern era as presidents have increasingly employed the statements to assert constitutional and legal objections to congressional enactments. President Bush issued more than 160 signing statements, many of which included multiple constitutional and statutory objections. While signing statements were somewhat common during the middle of the twentieth century, President Bush issued more of them and raised broader constitutional objections than were contained in previous presidents’ signing statements. President Bush’s use of the signing statements caused extensive debate. The American Bar Association published a report declaring these instruments to be “contrary to the rule of law and our constitutional separation of powers” when they “claim the authority or state the intention to disregard or decline to enforce all or part of a law. . . or to interpret such a law in a manner inconsistent with the clear intent of Congress.”

—J. David Alvis and Joseph Postell

Detainee Treatment Act of 2005

TITLE X—MATTERS RELATING TO DETAINEES

SEC. 1002. UNIFORM STANDARDS FOR THE INTERROGATION OF PERSONS UNDER THE DETENTION OF THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE.

(a) In General—No person in the custody or under the effective control of the Department of Defense or under detention in a Department of Defense facility shall be subject to any treatment or technique of interrogation not authorized by and listed in the United States Army Field Manual on Intelligence Interrogation. . . .

SEC. 1003. PROHIBITION ON CRUEL, INHUMAN, OR DEGRADING TREATMENT OR PUNISHMENT OF PERSONS UNDER CUSTODY OR CONTROL OF THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT.

(a) In General—No individual in the custody or under the physical control of the United States Government, regardless of nationality or physical location, shall be subject to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment.

(b) Construction—Nothing in this section shall be construed to impose any geographical limitation on the applicability of the prohibition against cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment under this section. . . .

(d) Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment Defined—In this section, the term “cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment” means the cruel, unusual, and inhumane treatment or punishment prohibited by the Fifth, Eighth, and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United States, as defined in the United States Reservations, Declarations and Understandings to the United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Forms of Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment done at New York, December 10, 1984.

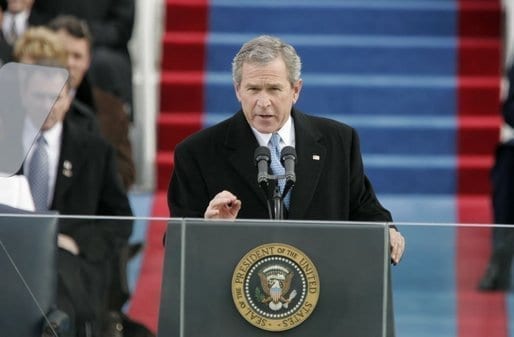

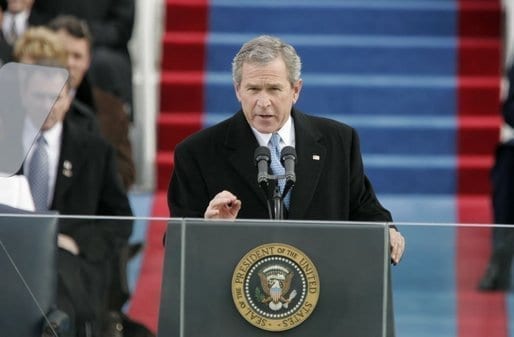

President George W. Bush’s Statement on Signing the Detainee Treatment Act

Today, I have signed into law H.R. 2863, the “Department of Defense, Emergency Supplemental Appropriations to Address Hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico, and Pandemic Influenza Act, 2006.”1 The act provides resources needed to fight the war on terror, help citizens of the Gulf states recover from devastating hurricanes, and protect Americans from a potential influenza pandemic. . . .

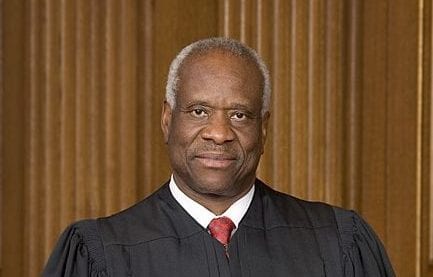

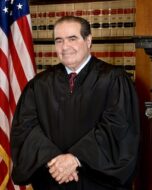

The executive branch shall construe Title X in Division A of the act, relating to detainees, in a manner consistent with the constitutional authority of the president to supervise the unitary executive branch and as commander in chief and consistent with the constitutional limitations on the judicial power, which will assist in achieving the shared objective of the Congress and the President, evidenced in Title X, of protecting the American people from further terrorist attacks. Further, in light of the principles enunciated by the Supreme Court of the United States in 2001 in Alexander v. Sandoval,2 and noting that the text and structure of Title X do not create a private right of action to enforce Title X, the executive branch shall construe Title X not to create a private right of action. Finally, given the decision of the Congress reflected in subsections 1005(e) and 1005(h) that the amendments made to section 2241 of title 28, United States Code, shall apply to past, present, and future actions, including applications for writs of habeas corpus, described in that section, and noting that section 1005 does not confer any constitutional right upon an alien detained abroad as an enemy combatant, the executive branch shall construe section 1005 to preclude the federal courts from exercising subject matter jurisdiction over any existing or future action, including applications for writs of habeas corpus, described in section 1005. . . .