No related resources

Introduction

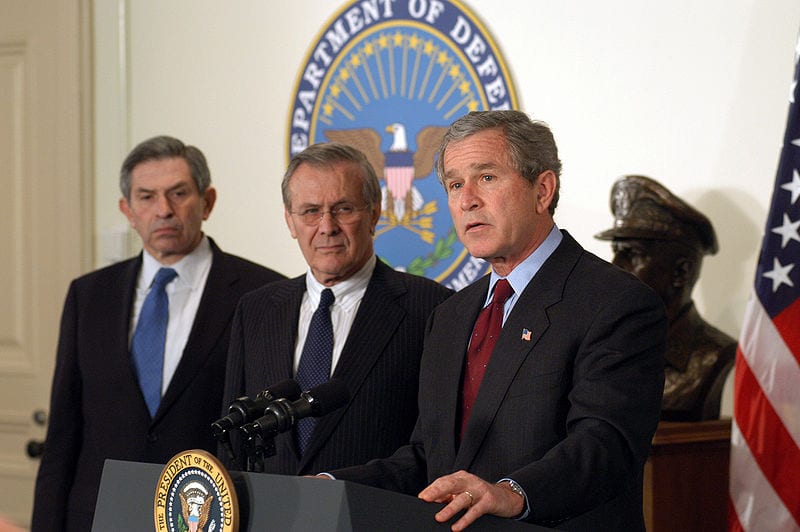

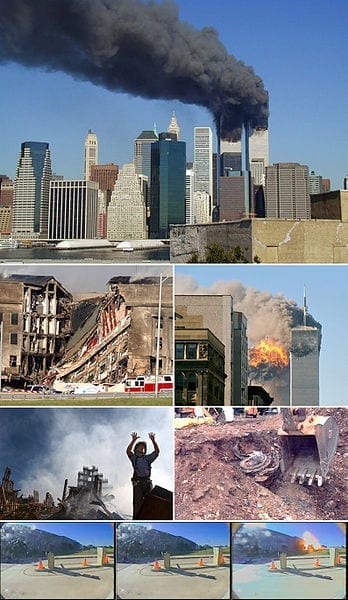

Washington, DC, passed a law in the 1970s that banned handgun possession by making it a crime to carry an unregistered firearm and prohibiting the registration of handguns; provided separately that no person may carry an unlicensed handgun, but authorized the police chief to issue one-year licenses; and required residents to keep lawfully owned firearms unloaded and dissembled or bound by a trigger lock or similar device. Dick Heller, a DC special policeman, applied to register a handgun he wished to keep at home, but the District refused. He filed suit, seeking, on Second Amendment grounds, to prevent the city from enforcing the bar on handgun registration, the licensing requirement insofar as it prohibited carrying an unlicensed firearm in the home, and the trigger-lock requirement insofar as it prohibited the use of functional firearms in the home. The District Court dismissed the suit but the DC Circuit reversed, holding that the Second Amendment protects an individual’s right to possess firearms and that the city’s total ban on handguns, as well as its requirement that firearms in the home be kept nonfunctional even when necessary for self-defense, violated that right. The District of Columbia appealed to the US Supreme Court, which voted 5-4 in favor of Heller, striking down the District’s law.

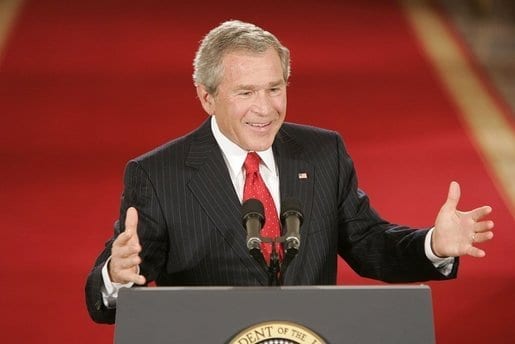

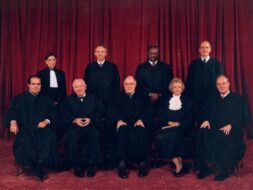

Heller is a notable decision for several reasons. It was the first time that the Supreme Court had given an extensive interpretation of the Second Amendment, a critical part of which was the Court’s unequivocal statement that the Amendment protects an individual right to possess certain firearms in the home for self-defense. Additionally, both the majority and the dissenters embraced the idea of interpreting the Amendment according to its original meaning, a break from the Court’s insistence on interpreting some other areas of the Bill of Rights (e.g., the EighthAmendment) according to a “living Constitution” approach. Finally, the Court’s decision invited challenges to other legal restrictions on firearms, including those by state and local governments. In McDonald v. Chicago (2010), the Court held by the same 5-4 majority that the Fourteenth Amendment applies the Second Amendment to the states, striking down Chicago’s ban on handgun possession. In 2018, the lead dissenter in Heller (retired Justice John Paul Stevens) went so far as to call publicly for “a constitutional amendment to get rid of the Second Amendment.”

Source: https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/07-290

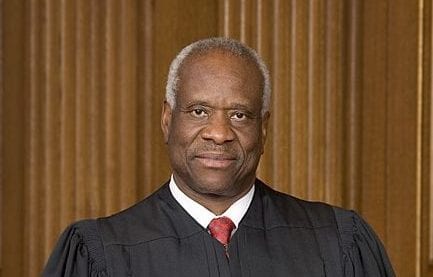

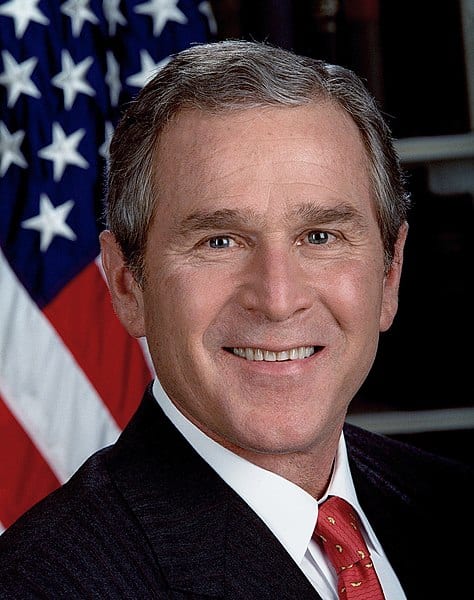

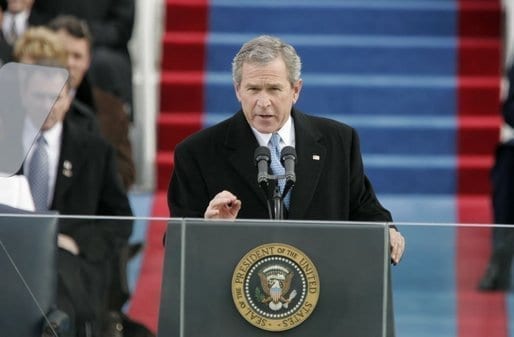

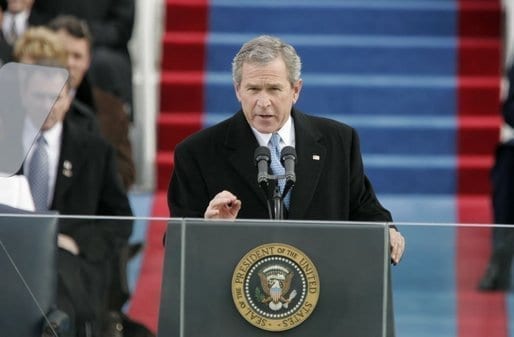

Justice SCALIA delivered the opinion of the Court, joined by Chief Justice ROBERTS and Justices KENNEDY, THOMAS, and ALITO.

The Second Amendment provides: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” . . .

The Second Amendment is naturally divided into two parts: its prefatory clause and its operative clause. The former does not limit the latter grammatically, but rather announces a purpose. The Amendment could be rephrased, “Because a well regulated Militia is necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed.” . . .

. . . The first salient feature of the operative clause is that it codifies a “right of the people.” The unamended Constitution and the Bill of Rights use the phrase “right of the people” two other times, in the First Amendment’s Assembly-and-Petition Clause and in the Fourth Amendment’s Search-and-Seizure Clause. The Ninth Amendment uses very similar terminology. . . . All three of these instances unambiguously refer to individual rights, not “collective” rights, or rights that may be exercised only through participation in some corporate body.

Three provisions of the Constitution refer to “the people” in a context other than “rights”—the famous preamble (“We the people”), section 2 of Article I (providing that “the people” will choose members of the House), and the Tenth Amendment (providing that those powers not given the Federal Government remain with “the States” or “the people”). Those provisions arguably refer to “the people” acting collectively—but they deal with the exercise or reservation of powers, not rights. Nowhere else in the Constitution does a “right” attributed to “the people” refer to anything other than an individual right. . . .

This contrasts markedly with the phrase “the militia” in the prefatory clause. . . . [T]he “militia” in colonial America consisted of a subset of “the people”—those who were male, able bodied, and within a certain age range. Reading the Second Amendment as protecting only the right to “keep and bear Arms” in an organized militia therefore fits poorly with the operative clause’s description of the holder of that right as “the people.”

We start therefore with a strong presumption that the Second Amendment right is exercised individually and belongs to all Americans.

. . . We move now from the holder of the right—“the people”—to the substance of the right: “to keep and bear Arms.”

Before addressing the verbs “keep” and “bear,” we interpret their object: “Arms.” The 18th-century meaning is no different from the meaning today. The 1773 edition of Samuel Johnson’s dictionary defined “arms” as “weapons of offence, or armour of defence.” Timothy Cunningham’s important 1771 legal dictionary defined “arms” as “any thing that a man wears for his defence, or takes into his hands, or useth in wrath to cast at or strike another.” . . .

We turn to the phrases “keep arms” and “bear arms.” Johnson defined “keep” as, most relevantly, “[t]o retain; not to lose,” and “[t]o have in custody.” Webster defined it as “[t]o hold; to retain in one’s power or possession.” No party has apprised us of an idiomatic meaning of “keep Arms.” Thus, the most natural reading of “keep Arms” in the Second Amendment is to “have weapons.” . . .

. . . “Keep arms” was simply a common way of referring to possessing arms, for militiamen and everyone else.

At the time of the founding, as now, to “bear” meant to “carry.” . . . When used with “arms,” however, the term has a meaning that refers to carrying for a particular purpose—confrontation. In Muscarello v. United States (1998), in the course of analyzing the meaning of “carries a firearm” in a federal criminal statute, Justice Ginsburg wrote that “[s]urely a most familiar meaning is, as the Constitution’s Second Amendment . . . indicate[s]: ‘wear, bear, or carry . . . upon the person or in the clothing or in a pocket, for the purpose . . . of being armed and ready for offensive or defensive action in a case of conflict with another person.’” . . . Although the phrase implies that the carrying of the weapon is for the purpose of “offensive or defensive action,” it in no way connotes participation in a structured military organization. . . .

The phrase “bear Arms” also had at the time of the founding an idiomatic meaning that was significantly different from its natural meaning: “to serve as a soldier, do military service, fight” or “to wage war.” But it unequivocally [emphasis in original] bore that idiomatic meaning only when followed by the preposition “against,” which was in turn followed by the target of the hostilities. (That is how, for example, our Declaration of Independence used the phrase: “He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country . . . .”) . . .

Justice Stevens points to a study . . . supposedly showing that the phrase “bear arms” was most frequently used in the military context. Of course . . . the fact that the phrase was commonly used in a particular context does not show that it is limited to that context, and, in any event, we have given many sources where the phrase was used in nonmilitary contexts [such as “bears arms for the purpose of killing game”].[1] . . . If “bear arms” means . . . simply the carrying of arms, a modifier can limit the purpose of the carriage (“for the purpose of self-defense” or “to make war against the King”). But if “bear arms” means, . . . as the dissent think, the carrying of arms only for military purposes, one simply cannot add “for the purpose of killing game.” The right “to carry arms in the militia for the purpose of killing game” is worthy of the mad hatter. Thus, these purposive qualifying phrases positively establish that “to bear arms” is not limited to military use.

Justice Stevens places great weight on James Madison’s inclusion of a conscientious-objector clause in his original draft of the Second Amendment: “but no person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms, shall be compelled to render military service in person.” He argues that this clause establishes that the drafters of the Second Amendment intended “bear Arms” to refer only to military service. [But] it was not meant to exempt from military service those who objected to going to war but had no scruples about personal gunfights. Quakers opposed the use of arms not just for militia service, but for any violent purpose whatsoever—so much so that Quaker frontiersmen were forbidden to use arms to defend their families. . . . Thus, the most natural interpretation of Madison’s deleted text is that those opposed to carrying weapons for potential violent confrontation would not be “compelled to render military service,” in which such carrying would be required. . . .

. . . Putting all of these textual elements together, we find that they guarantee the individual right to possess and carry weapons in case of confrontation. . . .

There seems to us no doubt, on the basis of both text and history, that the Second Amendment conferred an individual right to keep and bear arms. Of course the right was not unlimited, just as the First Amendment’s right of free speech was not. Thus, we do not read the Second Amendment to protect the right of citizens to carry arms for any sort of confrontation, just as we do not read the First Amendment to protect the right of citizens to speak for any purpose. Before turning to limitations upon the individual right, however, we must determine whether the prefatory clause of the Second Amendment comports with our interpretation of the operative clause.

The prefatory clause reads: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State . . . .”

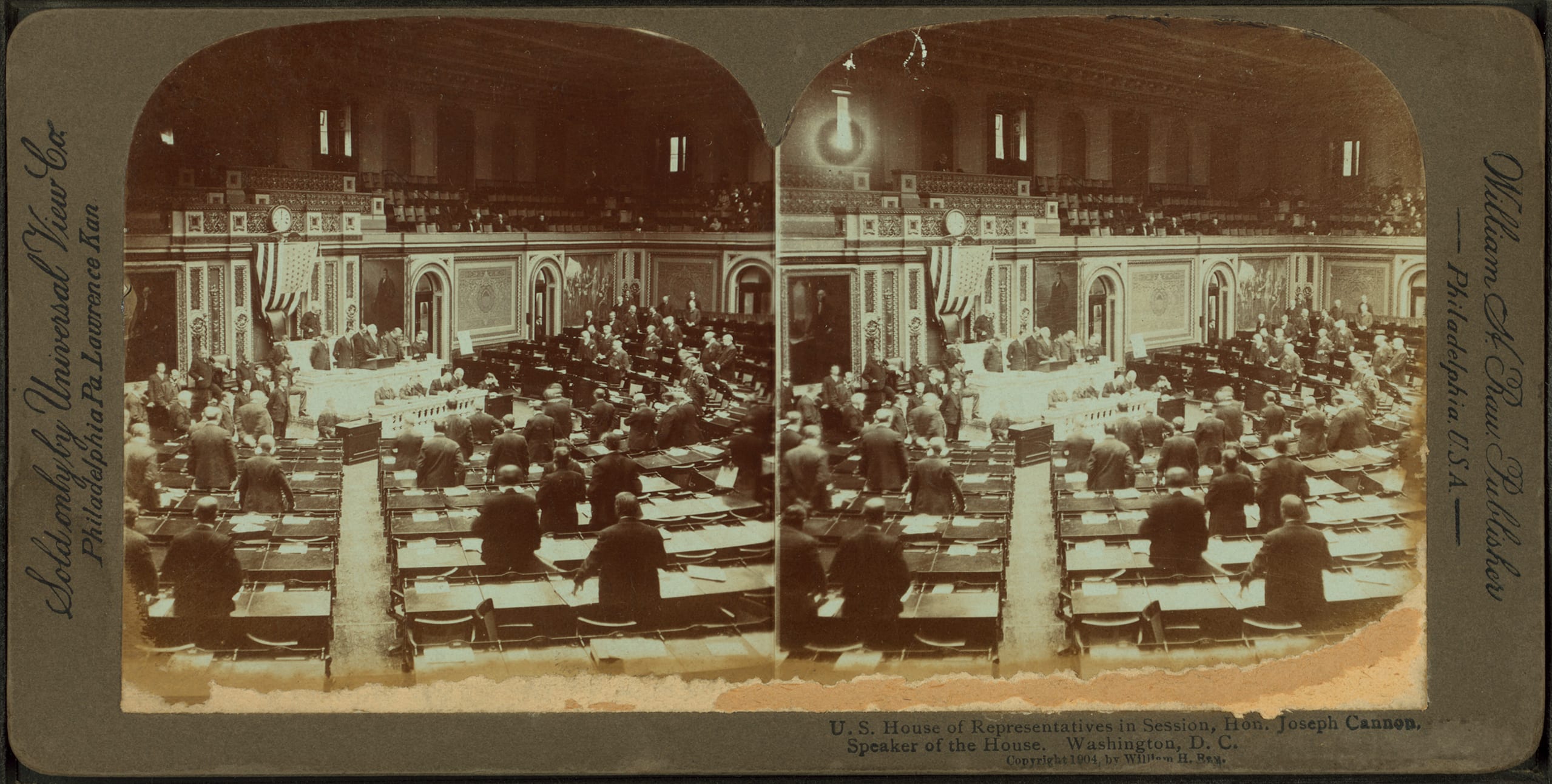

. . . In United States v. Miller (1939), we explained that “the Militia comprised all males physically capable of acting in concert for the common defense.” That definition comports with founding-era sources. See, e.g., The Federalist No. 46 (James Madison) (“near half a million of citizens with arms in their hands”). . . .

We reach the question, then: Does the preface fit with an operative clause that creates an individual right to keep and bear arms? It fits perfectly, once one knows the history that the founding generation knew. . . . That history showed that the way tyrants had eliminated a militia consisting of all the able-bodied men was not by banning the militia but simply by taking away the people’s arms, enabling a select militia or standing army to suppress political opponents. This is what had occurred in England that prompted codification of the right to have arms in the English Bill of Rights. . . .

It is therefore entirely sensible that the Second Amendment’s prefatory clause announces the purpose for which the right was codified: to prevent elimination of the militia. The prefatory clause does not suggest that preserving the militia was the only reason Americans valued the ancient right; most undoubtedly thought it even more important for self-defense and hunting. But the threat that the new Federal Government would destroy the citizens’ militia by taking away their arms was the reason that right—unlike some other English rights—was codified in a written Constitution. . . .

… If, as [Washington, DC] believes, the Second Amendment right is no more than the right to keep and use weapons as a member of an organized militia—if, that is, the organized militia is the sole institutional beneficiary of the Second Amendment’s guarantee—it does not assure the existence of a “citizens’ militia” as a safeguard against tyranny. For Congress retains plenary authority to organize the militia, which must include the authority to say who will belong to the organized force. . . . Thus, if [Washington, DC] is correct, the Second Amendment protects citizens’ right to use a gun in an organization from which Congress has plenary authority to exclude them. It guarantees a select militia of the sort the Stuart kings found useful, but not the people’s militia that was the concern of the founding generation. . . .

We now ask whether any of our precedents forecloses the conclusions we have reached about the meaning of the Second Amendment. . . .

Like most rights, the right secured by the Second Amendment is not unlimited. From Blackstone through the 19th-century cases, commentators and courts routinely explained that the right was not a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose. . . . Although we do not undertake an exhaustive historical analysis today of the full scope of the Second Amendment, nothing in our opinion should be taken to cast doubt on longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, or laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings, or laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms.

We also recognize another important limitation on the right to keep and carry arms. Miller said, as we have explained, that the sorts of weapons protected were those “in common use at the time. . . .”

It may be objected that if weapons that are most useful in military service—M-16 rifles and the like—may be banned, then the Second Amendment right is completely detached from the prefatory clause. But as we have said, the conception of the militia at the time of the Second Amendment’s ratification was the body of all citizens capable of military service, who would bring the sorts of lawful weapons that they possessed at home to militia duty. It may well be true today that a militia, to be as effective as militias in the 18th century, would require sophisticated arms that are highly unusual in society at large. Indeed, it may be true that no amount of small arms could be useful against modern-day bombers and tanks. But the fact that modern developments have limited the degree of fit between the prefatory clause and the protected right cannot change our interpretation of the right.

We turn finally to the law at issue here. . . . [T]he law totally bans handgun possession in the home. It also requires that any lawful firearm in the home be disassembled or bound by a trigger lock at all times, rendering it inoperable.

. . . [T]he inherent right of self-defense has been central to the Second Amendment right. The handgun ban amounts to a prohibition of an entire class of “arms” that is overwhelmingly chosen by American society for that lawful purpose. The prohibition extends, moreover, to the home, where the need for defense of self, family, and property is most acute. Under any of the standards of scrutiny that we have applied to enumerated constitutional rights, banning from the home “the most preferred firearm in the nation to ‘keep’ and use for protection of one’s home and family” would fail constitutional muster. . . .

It[2] is no answer to say, as [Washington, DC does], that it is permissible to ban the possession of handguns so long as the possession of other firearms (i.e., long guns) is allowed. It is enough to note . . . that the American people have considered the handgun to be the quintessential self-defense weapon. There are many reasons that a citizen may prefer a handgun for home defense: It is easier to store in a location that is readily accessible in an emergency; it cannot easily be redirected or wrestled away by an attacker; it is easier to use for those without the upper-body strength to lift and aim a long gun; it can be pointed at a burglar with one hand while the other hand dials the police. Whatever the reason, handguns are the most popular weapon chosen by Americans for self-defense in the home, and a complete prohibition of their use is invalid.

We must also address the District’s requirement . . . that firearms in the home be rendered and kept inoperable at all times. This makes it impossible for citizens to use them for the core lawful purpose of self-defense and is hence unconstitutional. . . .

Justice Breyer has devoted most of his separate dissent to the handgun ban. He says that, even assuming the Second Amendment is a personal guarantee of the right to bear arms, the District’s prohibition is valid. He first tries to establish this by founding-era historical precedent, pointing to various restrictive laws in the colonial period. These demonstrate, in his view, that the District’s law “imposes a burden upon gun owners that seems proportionately no greater than restrictions in existence at the time the Second Amendment was adopted.” Of the laws he cites, only one offers even marginal support for his assertion. A 1783 Massachusetts law forbade the residents of Boston to “take into” or “receive into” “any Dwelling House, Stable, Barn, Out-house, Ware-house, Store, Shop or other Building” loaded firearms, and permitted the seizure of any loaded firearms that “shall be found” there. That statute’s text and its prologue, which makes clear that the purpose of the prohibition was to eliminate the danger to firefighters posed by the “depositing of loaded Arms” in buildings, give reason to doubt that colonial Boston authorities would have enforced that general prohibition against someone who temporarily loaded a firearm to confront an intruder (despite the law’s application in that case). In any case, we would not stake our interpretation of the Second Amendment upon a single law, in effect in a single city, that contradicts the overwhelming weight of other evidence regarding the right to keep and bear arms for defense of the home. . . .

Justice Breyer moves on to make a broad jurisprudential point. . . . He proposes, explicitly at least, none of the traditionally expressed levels (strict scrutiny, intermediate scrutiny, rational basis), but rather a judge-empowering “interest-balancing inquiry” that “asks whether the statute burdens a protected interest in a way or to an extent that is out of proportion to the statute’s salutary effects upon other important governmental interests.” . . .

We know of no other enumerated constitutional right whose core protection has been subjected to a freestanding “interest-balancing” approach. The very enumeration of the right takes out of the hands of government—even the Third Branch of Government—the power to decide on a case-by-case basis whether the right is really worth insisting upon. A constitutional guarantee subject to future judges’ assessments of its usefulness is no constitutional guarantee at all. Constitutional rights are enshrined with the scope they were understood to have when the people adopted them, whether or not future legislatures or (yes) even future judges think that scope too broad. . . . The First Amendment contains the freedom-of-speech guarantee that the people ratified, which included exceptions for obscenity, libel, and disclosure of state secrets, but not for the expression of extremely unpopular and wrong-headed views. The Second Amendment is no different. Like the First, it is the very product of an interest-balancing by the people—which Justice Breyer would now conduct for them anew. And whatever else it leaves to future evaluation, it surely elevates above all other interests the right of law-abiding, responsible citizens to use arms in defense of hearth and home. . . .

In sum, we hold that the District’s ban on handgun possession in the home violates the Second Amendment, as does its prohibition against rendering any lawful firearm in the home operable for the purpose of immediate self-defense. Assuming that Heller is not disqualified from the exercise of Second Amendment rights, the District must permit him to register his handgun and must issue him a license to carry it in the home.

We are aware of the problem of handgun violence in this country, and we take seriously the concerns raised by the many amici who believe that prohibition of handgun ownership is a solution. The Constitution leaves the District of Columbia a variety of tools for combating that problem, including some measures regulating handguns. But the enshrinement of constitutional rights necessarily takes certain policy choices off the table. These include the absolute prohibition of handguns held and used for self-defense in the home. Undoubtedly some think that the Second Amendment is outmoded in a society where our standing army is the pride of our Nation, where well-trained police forces provide personal security, and where gun violence is a serious problem. That is perhaps debatable, but what is not debatable is that it is not the role of this Court to pronounce the Second Amendment extinct.

We affirm the judgment of the Court of Appeals.

It is so ordered.

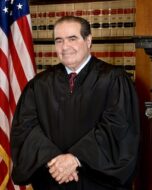

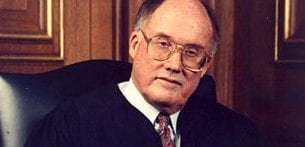

Justice STEVENS dissenting, joined by Justices SOUTER, GINSBERG, and BREYER.

… The centerpiece of the Court’s textual argument is its insistence that the words “the people” as used in the Second Amendment must have the same meaning, and protect the same class of individuals, as when they are used in the First and Fourth Amendments. . . . But the Court itself reads the Second Amendment to protect a “subset” significantly narrower than the class of persons protected by the First and Fourth Amendments; when it finally drills down on the substantive meaning of the Second Amendment, the Court limits the protected class to “law-abiding, responsible citizens.” But the class of persons protected by the First and Fourth Amendments is not so limited; for even felons (and presumably irresponsible citizens as well) may invoke the protections of those constitutional provisions. The Court offers no way to harmonize its conflicting pronouncements. . . .

Similarly, the words “the people” in the Second Amendment refer back to the object announced in the Amendment’s preamble. They remind us that it is the collective action of individuals having a duty to serve in the militia that the text directly protects and, perhaps more importantly, that the ultimate purpose of the Amendment was to protect the States’ share of the divided sovereignty created by the Constitution. . . .

. . . As used in the Second Amendment, the words “the people” do not enlarge the right to keep and bear arms to encompass use or ownership of weapons outside the context of service in a well-regulated militia.

“To keep and bear Arms”

Although the Court’s discussion of these words treats them as two “phrases”—as if they read “to keep” and “to bear”—they describe a unitary right: to possess arms if needed for military purposes and to use them in conjunction with military activities. . . .

…[T]he “right to keep and bear arms” protects only a right to possess and use firearms in connection with service in a state-organized militia.

The term “bear arms” is a familiar idiom. . . . It is derived from the Latin arma ferre, which, translated literally, means “to bear [ferre] war equipment [arma].” . . . The unmodified use of “bear arms” . . . refers most naturally to a military purpose, as evidenced by its use in literally dozens of contemporary texts. The absence of any reference to civilian uses of weapons tailors the text of the Amendment to the purpose identified in its preamble. But when discussing these words, the Court simply ignores the preamble. . . .

The Amendment’s use of the term “keep” in no way contradicts the military meaning conveyed by the phrase “bear arms” and the Amendment’s preamble. To the contrary, a number of state militia laws in effect at the time of the Second Amendment’s drafting used the term “keep” to describe the requirement that militia members store their arms at their homes, ready to be used for service when necessary. The Virginia military law, for example, ordered that “every one of the said officers, non-commissioned officers, and privates, shall constantly keep the aforesaid arms, accouterments, and ammunition, ready to be produced whenever called for by his commanding officer.” “[K]eep and bear arms” thus perfectly describes the responsibilities of a framing-era militia member. . . .

When each word in the text is given full effect, the Amendment is most naturally read to secure to the people a right to use and possess arms in conjunction with service in a well-regulated militia. Even if the meaning of the text were genuinely susceptible to more than one interpretation, the burden would remain on those advocating a departure from the purpose identified in the preamble and from settled law to come forward with persuasive new arguments or evidence. The textual analysis offered by respondent and[3] embraced by the Court falls far short of sustaining that heavy burden. . . .

[We cannot forget that James] Madison, charged with the task of assembling the proposals for amendments sent by the ratifying States, was the principal draftsman of the Second Amendment. . . .

. . . [H]is original draft . . . read: “The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed; a well-armed, and well-regulated militia being the best security of a free country; but no person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms, shall be compelled to render military service in person.”. . .

Madison’s initial inclusion of an exemption for conscientious objectors sheds revelatory light on the purpose of the Amendment. It confirms an intent to describe a duty as well as a right, and it unequivocally identifies the military character of both. . . .

The Court concludes its opinion by declaring that it is not the proper role of this Court to change the meaning of rights “enshrine[d]” in the Constitution. But the right the Court announces was not “enshrined” in the Second Amendment by the Framers; it is the product of today’s law-changing decision. . . .

The Court properly disclaims any interest in evaluating the wisdom of the specific policy choice challenged in this case, but it fails to pay heed to a far more important policy choice—the choice made by the Framers themselves. The Court would have us believe that over 200 years ago, the Framers made a choice to limit the tools available to elected officials wishing to regulate civilian uses of weapons, and to authorize this Court to use the common-law process of case-by-case judicial lawmaking to define the contours of acceptable gun control policy. Absent compelling evidence that is nowhere to be found in the Court’s opinion, I could not possibly conclude that the Framers made such a choice.

For these reasons, I respectfully dissent.

Justice BREYER dissenting, joined by Justices STEVENS, SOUTER, and GINSBERG.

. . . I shall show that the District’s law is consistent with the Second Amendment even if that Amendment is interpreted as protecting a wholly separate interest in individual self-defense. That is so because the District’s regulation, which focuses upon the presence of handguns in high-crime urban areas, represents a permissible legislative response to a serious, indeed life-threatening, problem. . . .

. . . [C]olonial history itself offers important examples of the kinds of gun regulation that citizens would then have thought compatible with the “right to keep and bear arms,” whether embodied in Federal or State Constitutions, or the background common law. And those examples include substantial regulation of firearms in urban areas, including regulations that imposed obstacles to the use of firearms for the protection of the home.

Boston, Philadelphia, and New York City, the three largest cities in America during that period, all restricted the firing of guns within city limits to at least some degree. . . .

Furthermore, several towns and cities (including Philadelphia, New York, and Boston) regulated, for fire-safety reasons, the storage of gunpowder, a necessary component of an operational firearm. Boston’s law in particular impacted the use of firearms in the home very much as the District’s law does today. Boston’s gunpowder law imposed a 10 fine [sic] upon “any Person” who “shall take into any Dwelling-House, Stable, Barn, Out-house, Ware-house, Store, Shop, or other Building, within the Town of Boston, any . . . Fire-Arm, loaded with, or having Gun-Powder.” Even assuming . . . that this law included an implicit self-defense exception, it would nevertheless have prevented a homeowner from keeping in his home a gun that he could immediately pick up and use against an intruder. Rather, the homeowner would have had to get the gunpowder and load it into the gun, an operation that would have taken a fair amount of time to perform. . . .

. . . [T]he gunpowder-storage laws would have burdened armed self-defense, even if they did not completely prohibit it.

This historical evidence demonstrates that a self-defense assumption is the beginning, rather than the end, of any constitutional inquiry. . . .

I therefore begin by asking a process-based question: How is a court to determine whether a particular firearm regulation (here, the District’s restriction on handguns) is consistent with the Second Amendment? What kind of constitutional standard should the court use? How high a protective hurdle does the Amendment erect? . . .

I would simply adopt . . . an interest-balancing inquiry explicitly. . . .

In applying this kind of standard the Court normally defers to a legislature’s empirical judgment in matters where a legislature is likely to have greater expertise and greater institutional factfinding capacity. Nonetheless, a court, not a legislature, must make the ultimate constitutional conclusion, exercising its “independent judicial judgment” in light of the whole record to determine whether a law exceeds constitutional boundaries.

The above-described approach seems preferable to a more rigid approach here for a further reason. Experience as much as logic has led the Court to decide that in one area of constitutional law or another the interests are likely to prove stronger on one side of a typical constitutional case than on the other. . . .

The . . . District . . . requires that the lawful owner of a firearm keep his weapon “unloaded and disassembled or bound by a trigger lock or similar device” unless it is kept at his place of business or being used for lawful recreational purposes. The only dispute regarding this provision appears to be whether the Constitution requires an exception that would allow someone to render a firearm operational when necessary for self-defense (i.e., that the firearm may be operated under circumstances where the common law would normally permit a self-defense justification in defense against a criminal charge). . . .

The District . . . prohibits (in most cases) the registration of a handgun within the District. Because registration is a prerequisite to firearm possession, the effect of this provision is generally to prevent people in the District from possessing handguns. . . .

No one doubts the constitutional importance of the statute’s basic objective, saving lives. . . . . . [D]eference to legislative judgment seems particularly appropriate here, where the judgment has been made by a local legislature, with particular knowledge of local problems and insight into appropriate local solutions. . . . Different localities may seek to solve similar problems in different ways, and a “city must be allowed a reasonable opportunity to experiment with solutions to admittedly serious problems.” . . . We owe that democratic process some substantial weight in the constitutional calculus.

For these reasons, I conclude that the District’s statute properly seeks to further the sort of life-preserving and public-safety interests that the Court has called “compelling.”

I next assess the extent to which the District’s law burdens the interests that the Second Amendment seeks to protect. . . .

The District’s law does prevent a resident from keeping a loaded handgun in his home. And it consequently makes it more difficult for the householder to use the handgun for self-defense in the home against intruders, such as burglars. . . . To that extent the law burdens to some degree an interest in self-defense that for present purposes I have assumed the Amendment seeks to further.

In weighing needs and burdens, we must take account of the possibility that there are reasonable, but less restrictive alternatives. Are there other potential measures that might similarly promote the same goals while imposing lesser restrictions? Here I see none.

The reason there is no clearly superior, less restrictive alternative to the District’s handgun ban is that the ban’s very objective is to reduce significantly the number of handguns in the District, say, for example, by allowing a law enforcement officer immediately to assume that any handgun he sees is an illegal handgun. And there is no plausible way to achieve that objective other than to ban the guns. . . .

. . . [T]oday’s decision . . . will have unfortunate consequences. The decision will encourage legal challenges to gun regulation throughout the Nation. Because it says little about the standards used to evaluate regulatory decisions, it will leave the Nation without clear standards for resolving those challenges. And litigation over the course of many years, or the mere specter of such litigation, threatens to leave cities without effective protection against gun violence and accidents during that time.

As important, the majority’s decision threatens severely to limit the ability of more knowledgeable, democratically elected officials to deal with gun-related problems. The majority says that it leaves the District “a variety of tools for combating” such problems. It fails to list even one seemingly adequate replacement for the law it strikes down. I can understand how reasonable individuals can disagree about the merits of strict gun control as a crime-control measure, even in a totally urbanized area. But I cannot understand how one can take from the elected branches of government the right to decide whether to insist upon a handgun-free urban populace in a city now facing a serious crime problem and which, in the future, could well face environmental or other emergencies that threaten the breakdown of law and order. . . .

Nor is it at all clear to me how the majority decides which loaded “arms” a homeowner may keep. The majority says that that Amendment protects those weapons “typically possessed by law-abiding citizens for lawful purposes.” This definition conveniently excludes machineguns, but permits handguns, which the majority describes as “the most popular weapon chosen by Americans for self-defense in the home.” But what sense does this approach make? According to the majority’s reasoning, if Congress and the States lift restrictions on the possession and use of machineguns, and people buy machineguns to protect their homes, the Court will have to reverse course and find that the Second Amendment does, in fact, protect the individual self-defense-related right to possess a machinegun. On the majority’s reasoning, if tomorrow someone invents a particularly useful, highly dangerous self-defense weapon, Congress and the States had better ban it immediately, for once it becomes popular Congress will no longer possess the constitutional authority to do so. In essence, the majority determines what regulations are permissible by looking to see what existing regulations permit. There is no basis for believing that the Framers intended such circular reasoning. . . .

For these reasons, I conclude that the District’s measure is a proportionate, not a disproportionate, response to the compelling concerns that led the District to adopt it. And, for these reasons as well as the independently sufficient reasons set forth by Justice Stevens, I would find the District’s measure consistent with the Second Amendment’s demands.

With respect, I dissent.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.