No related resources

Introduction

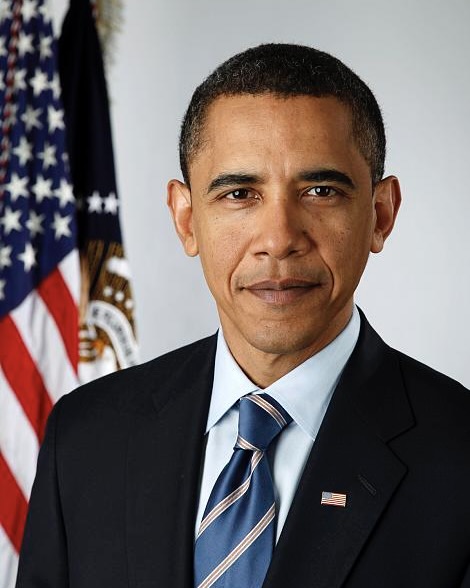

Barack Obama (1961–) was elected president in 2008. The first African American to hold this office, he spoke proudly during his campaign of his mixed heritage as the son of “a black man from Kenya and a white woman from Kansas.” Before becoming president, he served as a Democratic senator from Illinois. He came to office in the midst of a serious economic recession, to which he alluded in this speech. As he looked forward to a reelection campaign in 2012, Obama traveled to Osawatomie, Kansas, the scene of a famous speech by a former Republican president, Theodore Roosevelt. In his speech, Obama explained how he thought America should deal with the economic consequences not only of the recession but also of the longer-term changes to the economy brought about by the widespread use of information technology and openness to trade, financial movements, and migration across national borders. The United States had encouraged this openness since the end of World War II, but Obama argued that more had to be done to deal with its consequences.

Source: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2011/12/06/remarks-president-economy-osawatomie-kansas.

My grandparents served during World War II. He was a soldier in Patton’s Army; she was a worker on a bomber assembly line.1 And together, they shared the optimism of a nation that triumphed over the Great Depression and over fascism. They believed in an America where hard work paid off, and responsibility was rewarded, and anyone could make it if they tried—no matter who you were, no matter where you came from, no matter how you started out.

And these values gave rise to the largest middle class and the strongest economy that the world has ever known. It was here in America that the most productive workers, the most innovative companies turned out the best products on Earth. And you know what? Every American shared in that pride and in that success—from those in the executive suites to those in middle management to those on the factory floor. So you could have some confidence that if you gave it your all, you’d take enough home to raise your family and send your kids to school and have your health care covered, put a little away for retirement.

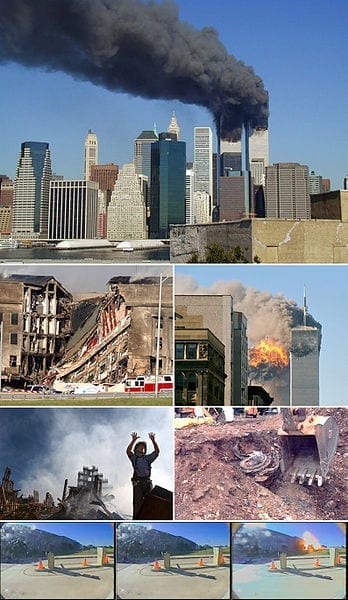

Today, we’re still home to the world’s most productive workers. We’re still home to the world’s most innovative companies. But for most Americans, the basic bargain that made this country great has eroded. Long before the recession hit,2 hard work stopped paying off for too many people. Fewer and fewer of the folks who contributed to the success of our economy actually benefited from that success. Those at the very top grew wealthier from their incomes and their investments—wealthier than ever before. But everybody else struggled with costs that were growing and paychecks that weren’t—and too many families found themselves racking up more and more debt just to keep up.

And ever since [the recession], there’s been a raging debate over the best way to restore growth and prosperity, restore balance, restore fairness. Throughout the country, it’s sparked protests and political movements—from the Tea Party to the people who’ve been occupying the streets of New York and other cities.3 It’s left Washington in a near-constant state of gridlock. It’s been the topic of heated and sometimes colorful discussion among the men and women running for president.

But, Osawatomie, this is not just another political debate. This is the defining issue of our time. This is a make-or-break moment for the middle class, and for all those who are fighting to get into the middle class. Because what’s at stake is whether this will be a country where working people can earn enough to raise a family, build a modest savings, own a home, secure their retirement.

Now, in the midst of this debate, there are some who seem to be suffering from a kind of collective amnesia. After all that’s happened, after the worst economic crisis, the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, they want to return to the same practices that got us into this mess. In fact, they want to go back to the same policies that stacked the deck against middle-class Americans for way too many years. And their philosophy is simple: We are better off when everybody is left to fend for themselves and play by their own rules.

I am here to say they are wrong. I’m here in Kansas to reaffirm my deep conviction that we’re greater together than we are on our own. I believe that this country succeeds when everyone gets a fair shot, when everyone does their fair share, when everyone plays by the same rules. These aren’t Democratic values or Republican values. These aren’t 1 percent values or 99 percent values.4 They’re American values. And we have to reclaim them.

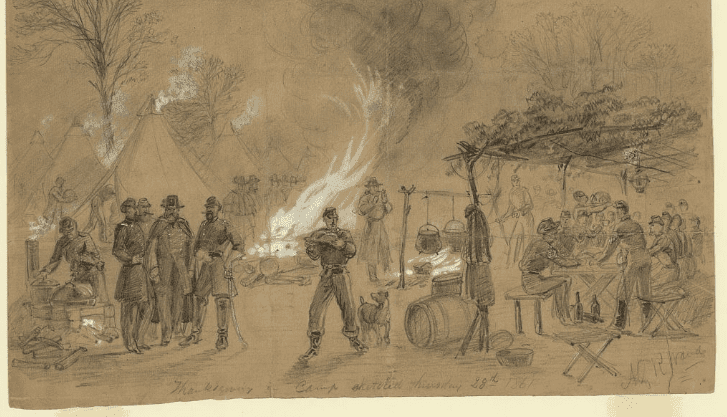

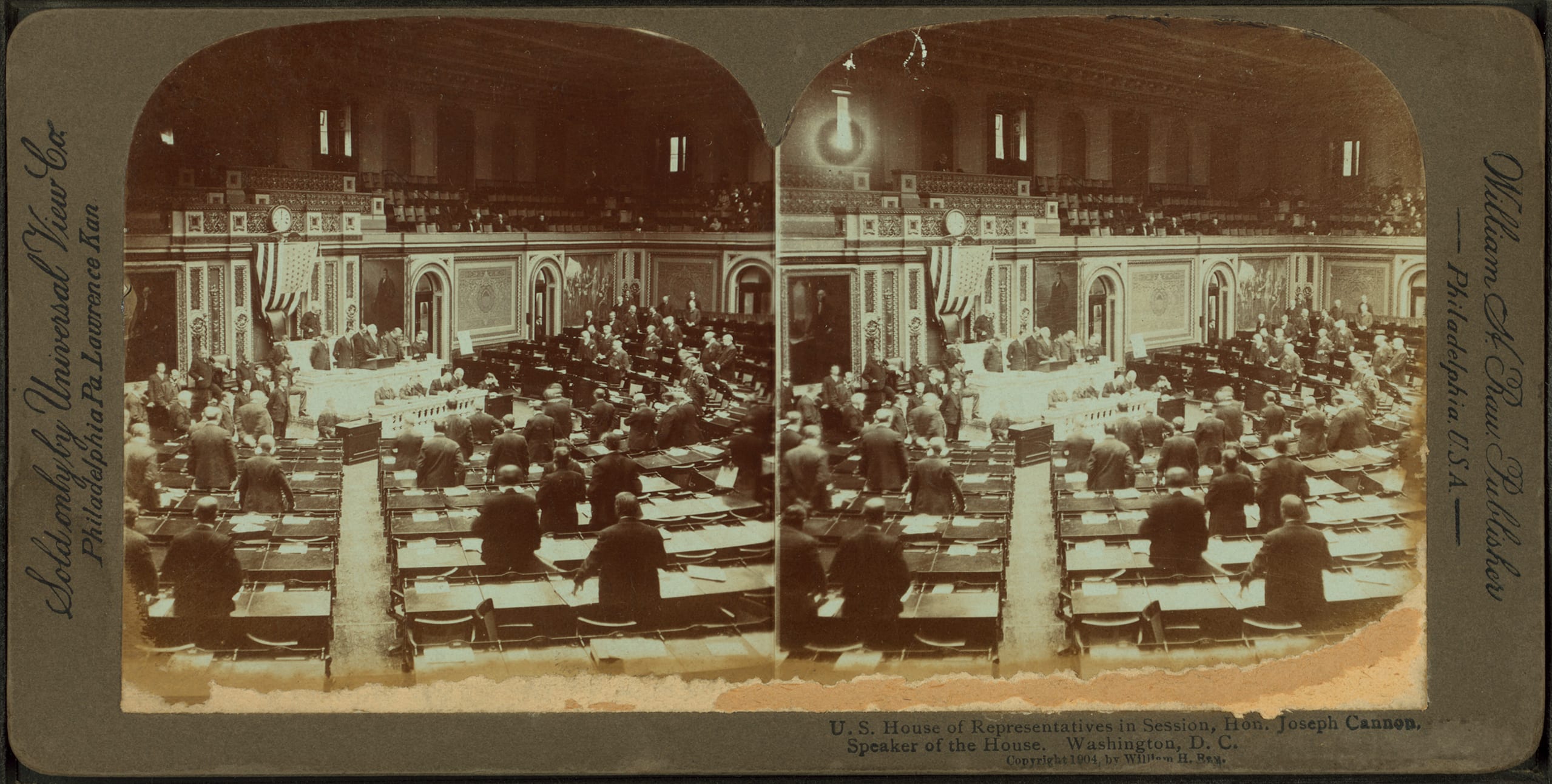

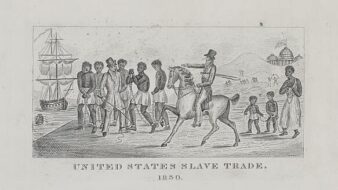

You see, this isn’t the first time America has faced this choice. At the turn of the last century, when a nation of farmers was transitioning to become the world’s industrial giant, we had to decide: Would we settle for a country where most of the new railroads and factories were being controlled by a few giant monopolies that kept prices high and wages low? Would we allow our citizens and even our children to work ungodly hours in conditions that were unsafe and unsanitary? Would we restrict education to the privileged few? Because there were people who thought massive inequality and exploitation of people was just the price you pay for progress.

Theodore Roosevelt disagreed. He was the Republican son of a wealthy family. He praised what the titans of industry had done to create jobs and grow the economy. He believed then what we know is true today, that the free market is the greatest force for economic progress in human history. It’s led to a prosperity and a standard of living unmatched by the rest of the world.

But Roosevelt also knew that the free market has never been a free license to take whatever you can from whomever you can. He understood the free market only works when there are rules of the road that ensure competition is fair and open and honest. And so he busted up monopolies, forcing those companies to compete for consumers with better services and better prices. And today, they still must. He fought to make sure businesses couldn’t profit by exploiting children or selling food or medicine that wasn’t safe. And today, they still can’t.

And in 1910, Teddy Roosevelt came here to Osawatomie and he laid out his vision for what he called a New Nationalism. “Our country,” he said, “. . . means nothing unless it means the triumph of a real democracy . . . of an economic system under which each man shall be guaranteed the opportunity to show the best that there is in him.”5

Now, for this, Roosevelt was called a radical. He was called a socialist, even a communist. But today, we are a richer nation and a stronger democracy because of what he fought for in his last campaign: an eight-hour workday and a minimum wage for women, insurance for the unemployed and for the elderly, and those with disabilities; political reform and a progressive income tax.

Today, over one hundred years later, our economy has gone through another transformation. Over the last few decades, huge advances in technology have allowed businesses to do more with less, and it’s made it easier for them to set up shop and hire workers anywhere they want in the world. And many of you know firsthand the painful disruptions this has caused for a lot of Americans.

Factories where people thought they would retire suddenly picked up and went overseas, where workers were cheaper. Steel mills that needed one thousand employees are now able to do the same work with one hundred employees, so layoffs too often became permanent, not just a temporary part of the business cycle. And these changes didn’t just affect blue-collar workers. If you were a bank teller or a phone operator or a travel agent, you saw many in your profession replaced by ATMs and the Internet.

Today, even higher-skilled jobs like accountants and middle management can be outsourced to countries like China or India. And if you’re somebody whose job can be done cheaper by a computer or someone in another country, you don’t have a lot of leverage with your employer when it comes to asking for better wages or better benefits, especially since fewer Americans today are part of a union.

Now, just as there was in Teddy Roosevelt’s time, there is a certain crowd in Washington who, for the last few decades, have said, let’s respond to this economic challenge with the same old tune. “The market will take care of everything,” they tell us. If we just cut more regulations and cut more taxes—especially for the wealthy—our economy will grow stronger. Sure, they say, there will be winners and losers. But if the winners do really well, then jobs and prosperity will eventually trickle down to everybody else. And, they argue, even if prosperity doesn’t trickle down, well, that’s the price of liberty.

Now, it’s a simple theory. And we have to admit, it’s one that speaks to our rugged individualism and our healthy skepticism of too much government. That’s in America’s DNA. And that theory fits well on a bumper sticker. But here’s the problem: It doesn’t work. It has never worked. It didn’t work when it was tried in the decade before the Great Depression. It’s not what led to the incredible postwar booms of the ’50s and ’60s. And it didn’t work when we tried it during the last decade. I mean, understand, it’s not as if we haven’t tried this theory. . . .

We simply cannot return to this brand of “you’re on your own” economics if we’re serious about rebuilding the middle class in this country. We know that it doesn’t result in a strong economy. It results in an economy that invests too little in its people and in its future. We know it doesn’t result in a prosperity that trickles down. It results in a prosperity that’s enjoyed by fewer and fewer of our citizens. . . .

Now, this kind of inequality—a level that we haven’t seen since the Great Depression—hurts us all. When middle-class families can no longer afford to buy the goods and services that businesses are selling, when people are slipping out of the middle class, it drags down the entire economy from top to bottom. America was built on the idea of broad-based prosperity, of strong consumers all across the country. That’s why a CEO like Henry Ford made it his mission to pay his workers enough so that they could buy the cars he made. It’s also why a recent study showed that countries with less inequality tend to have stronger and steadier economic growth over the long run. . . .

. . .[G]aping inequality gives lie to the promise that’s at the very heart of America: that this is a place where you can make it if you try. We tell people—we tell our kids—that in this country, even if you’re born with nothing, work hard and you can get into the middle class. We tell them that your children will have a chance to do even better than you do. That’s why immigrants from around the world historically have flocked to our shores. . . .

. . . But the idea that . . . children might not have a chance to climb out of that situation and back into the middle class, no matter how hard they work? That’s inexcusable. It is wrong. It flies in the face of everything that we stand for.

Now, fortunately, that’s not a future that we have to accept, because there’s another view about how we build a strong middle class in this country—a view that’s truer to our history, a vision that’s been embraced in the past by people of both parties for more than 200 years.

It’s not a view that we should somehow turn back technology or put up walls around America. It’s not a view that says we should punish profit or success or pretend that government knows how to fix all of society’s problems. It is a view that says in America we are greater together—when everyone engages in fair play and everybody gets a fair shot and everybody does their fair share.

So what does that mean for restoring middle-class security in today’s economy? Well, it starts by making sure that everyone in America gets a fair shot at success. . . .It starts by making education a national mission—a national mission. Government and businesses, parents and citizens. In this economy, a higher education is the surest route to the middle class. The unemployment rate for Americans with a college degree or more is about half the national average. And their incomes are twice as high as those who don’t have a high school diploma. . . .

In today’s innovation economy, we also need a world-class commitment to science and research, the next generation of high-tech manufacturing.

. . . We should be giving people the chance to get new skills and training at community colleges so they can learn how to make wind turbines and semiconductors and high-powered batteries. And by the way, if we don’t have an economy that’s built on bubbles and financial speculation, our best and brightest won’t all gravitate towards careers in banking and finance. . . .

Today, manufacturers and other companies are setting up shop in the places with the best infrastructure to ship their products, move their workers, communicate with the rest of the world. And that’s why the over 1 million construction workers who lost their jobs when the housing market collapsed, they shouldn’t be sitting at home with nothing to do. They should be rebuilding our roads and our bridges, laying down faster railroads and broadband, modernizing our schools—all the things other countries are already doing to attract good jobs and businesses to their shores.

Yes, business, and not government, will always be the primary generator of good jobs with incomes that lift people into the middle class and keep them there. But as a nation, we’ve always come together, through our government, to help create the conditions where both workers and businesses can succeed. And historically, that hasn’t been a partisan idea. Franklin Roosevelt worked with Democrats and Republicans to give veterans of World War II—including my grandfather, Stanley Dunham—the chance to go to college on the G.I. Bill. It was a Republican president, Dwight Eisenhower, a proud son of Kansas, who started the Interstate Highway System and doubled down on science and research to stay ahead of the Soviets.

Of course, those productive investments cost money. They’re not free. And so we’ve also paid for these investments by asking everybody to do their fair share. . . .

In the long term, we have to rethink our tax system more fundamentally. We have to ask ourselves: Do we want to make the investments we need in things like education and research and high-tech manufacturing—all those things that helped make us an economic superpower? Or do we want to keep in place the tax breaks for the wealthiest Americans in our country? Because we can’t afford to do both. That is not politics. That’s just math. . . .

Investing in things like education that give everybody a chance to succeed. A tax code that makes sure everybody pays their fair share. And laws that make sure everybody follows the rules. That’s what will transform our economy. That’s what will grow our middle class again. In the end, rebuilding this economy based on fair play, a fair shot, and a fair share will require all of us to see that we have a stake in each other’s success. And it will require all of us to take some responsibility. . . .

And it will require American business leaders to understand that their obligations don’t just end with their shareholders. . . . This broader obligation can take many forms. At a time when the cost of hiring workers in China is rising rapidly, it should mean more CEOs deciding that it’s time to bring jobs back to the United States, not just because it’s good for business, but because it’s good for the country that made their business and their personal success possible. . . .

. . . Our success has never just been about survival of the fittest. It’s about building a nation where we’re all better off. We pull together. We pitch in. We do our part. We believe that hard work will pay off, that responsibility will be rewarded, and that our children will inherit a nation where those values live on. . . .

“We are all Americans,” Teddy Roosevelt told [an earlier audience in Osawatomie]. “Our common interests are as broad as the continent.” In the final years of his life, Roosevelt took that same message all across this country, from tiny Osawatomie to the heart of New York City, believing that no matter where he went, no matter who he was talking to, everybody would benefit from a country in which everyone gets a fair chance.

And well into our third century as a nation, we have grown and we’ve changed in many ways since Roosevelt’s time. The world is faster and the playing field is larger and the challenges are more complex. But what hasn’t changed—what can never change—are the values that got us this far. We still have a stake in each other’s success. We still believe that this should be a place where you can make it if you try. And we still believe, in the words of the man who called for a New Nationalism all those years ago, “The fundamental rule of our national life,” he said, “the rule which underlies all others—is that, on the whole, and in the long run, we shall go up or down together.” And I believe America is on the way up.

Thank you. God bless you. God bless the United States of America

- 1. Obama referred to his maternal grandparents

- 2. From December 2007 to June 2009, in what is sometimes referred to as the Great Recession, the GDP declined about 5 percent. During the Great Depression (August 1929–March 1933) the GDP declined about 26 percent.

- 3. The Tea Party was a political movement that called for lower taxes in order to decrease the deficit and the national debt. Occupy Wall Street was a political movement that called for reducing economic inequality.

- 4. The phrase “1 percent values” refers to the values of the richest 1 percent of the American population.

- 5. "The New Nationalism".

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.