No study questions

No related resources

In the fourth act of “Henry IV” the King on his death-bed gives his son and heir the ancient advice dear to the hearts of rulers in dire straits at home:

I … had a purpose now

To lead out many to the Holy Land,

Lest rest and lying still might make them look Too near unto my state. Therefore, my Harry, Be it thy course, to busy giddy minds

With foreign quarrels; that action, hence borne out, May waste the memory of the former days.

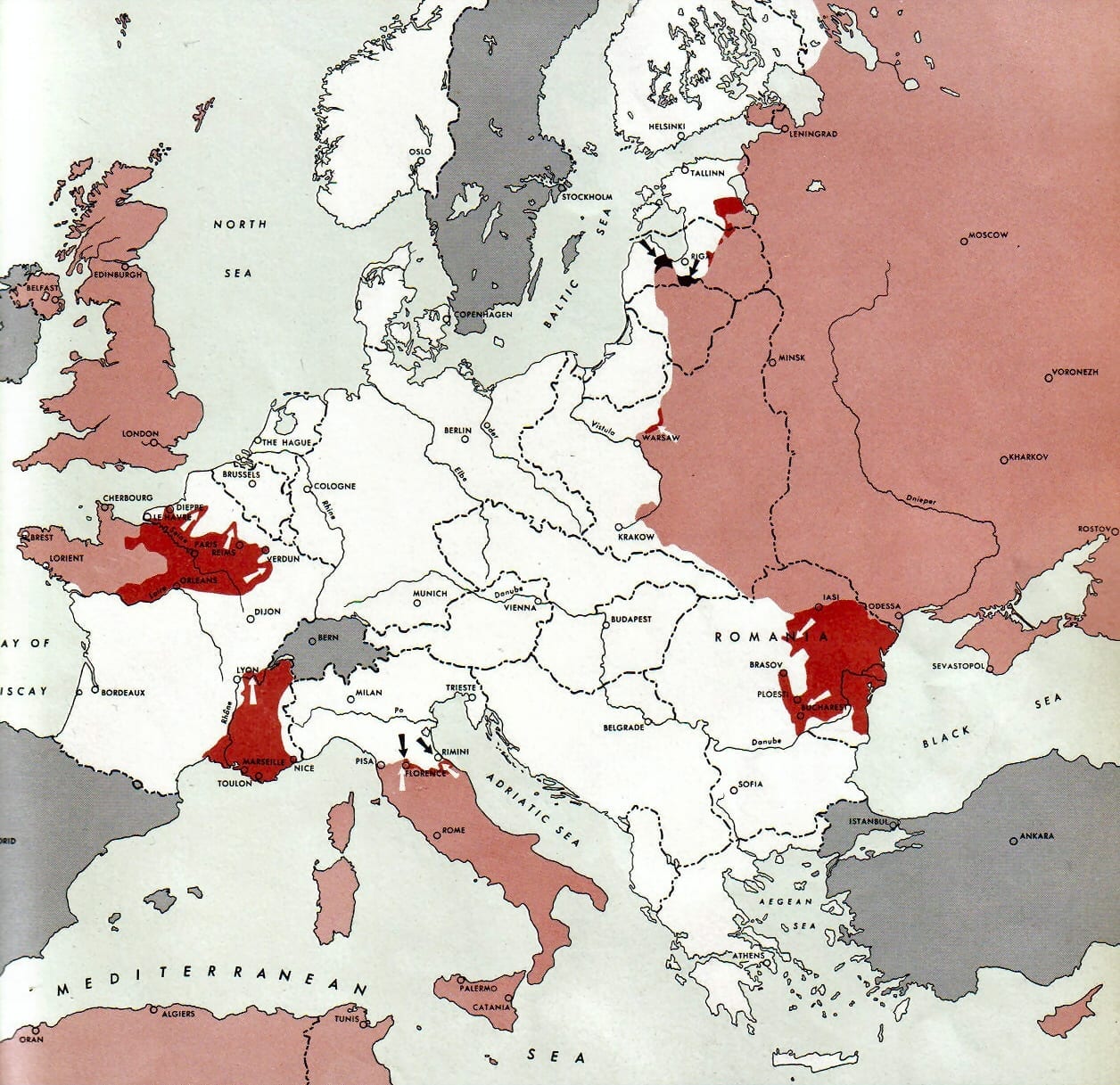

On what … should the foreign policy of the United States be based? Here is one answer and it is not excogitated in any professor’s study or supplied by political agitators. It is the doctrine formulated by George Washington, supplemented by James Monroe, and followed by the Government of the United States until near the end of the nineteenth century, when the frenzy for foreign adventurism burst upon the country. This doctrine is simple. Europe has a set of “primary interests” which have little or no relation to us, and is constantly vexed by “ambition, rival ship, interest, humor, or caprice.” The United States is a continental power separated from Europe by a wide ocean which, despite all changes in warfare; is still a powerful asset of defense. In the ordinary or regular vicissitudes of European politics the United States should not become implicated by any permanent ties. We should promote commerce, but force “nothing.” We should steer dear of hates and loves. We should maintain correct and formal relations with all established governments without respect to their forms or their religions, whether Christian, Mohammedan, Shinto, or what have you. Efforts of any European powers to seize more colonies or to oppress independent states in this hemisphere, or to extend their systems of despotism to the New World will be regarded as a matter of concern to the United States as soon as they are immediately threatened and begin to assume tangible shape.

This policy was stated positively in the early days of our Repulic. It was clear. It was definite. It gave the powers of the earth something they could understand and count upon in adjusting their policies and conflicts. It was not only stated. It was acted upon with a high degree of consistency until the great frenzy overtook us. It enabled the American people to go ahead under the principles of 1776, conquering a continent and building here a civilization which, with all its faults, has precious merits for us and is, at all events, our own. Under the shelter of this doctrine, human beings were set free to see what they could do on this continent, when emancipated from the privilege-encrusted institutions of Europe and from entanglement in the endless revolutions and wars of that continent.

Grounded in strong common sense, based on deep and bitter experience, Washington’s doctrine has remained a tenacious heritage, despite the hectic interludes of the past fifty years. Owing to the growth of our nation, the development of our own industries, the expulsion of Spain from this hemisphere, and the limitations now imposed upon British ambition by European pressures, the United States can pursue this policy more securely and more effectively today than at any time in our history. In an economic sense the United States is far more independent than it was in 1783, when the Republic was launched and, what is more, is better able to defend itself against all comers. Why, as Washington asked, quit our own to stand on foreign ground?

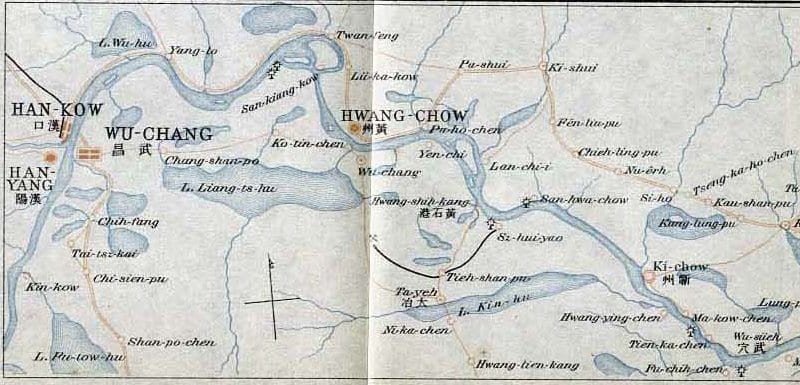

This is a policy founded upon our geographical position and our practical interests. It can be maintained by appropriate military and naval establishments. Beyond its continental zone and adjacent waters, in Latin America, the United States should have a care; but it is sheer folly to go into hysterics and double military and naval expenditures on the rumor that Hitler or Mussolini is about to seize Brazil, or that the Japanese are building gun emplacements in Costa Rica. Beyond this hemisphere, the United States should leave disputes over territory, over the ambitions of warriors, over the intrigues of hierarchies, over forms of government, over passing myths known as ideologies—all to the nations and peoples immediately and directly affected. They have more knowledge and power in the premises than have the people and the Government of the United States.

This foreign policy for the United States is based upon a recognition of the fact that no kind of international drum beating, conferring, and trading can do anything material to set our industries in full motion, raise the country from the deeps of the depression. Foreign trade is important, no doubt, but the main support for our American life is production and distribution in the United States and the way out of the present economic morass lies in the acceleration of this production and distribution at home, by domestic measures. Nothing that the United States can do in foreign negotiations can raise domestic production to the hundred billions a year that we need to put our national life, our democracy, on a foundation of internal security which. will relax the present tensions and hatreds.

It is a fact, stubborn and inescapable, that since the year 1900 the annual value of American goods exported has never risen above ten per cent of the total value of exportable or movable goods produced in the United States, except during the abnormal conditions of the war years. The exact percentage was 9.7 in 1914, 9.8 in 1929, and 7.3 in 1931. If experience is any guide we may expect the amount of exportable goods actually exported to be about ten per cent of the total, and the amount consumed at home to be about ninety per cent. High tariff or low tariff, little Navy or big, good neighbor policy or saber-rattling policy, hot air or cold air, this proportion seems to be in the nature of a fixed law, certainly more fixed than most of the so-called laws of political economy.

Since this is so, then why all the furor about attaining full prosperity by “increasing” our foreign trade? Why not apply stimulants to domestic production on which we can act directly? I can conceive of no reason for all this palaver except to divert the attention of the American people from things they can do at home to things they cannot do abroad.

In the rest of the world, outside this hemisphere, our interests are remote and our power to enforce our will is relatively slight. Nothing we can do for Europeans will substantially increase our trade or add to our, or their, well-being. Nothing we can do for Asiatics will materially increase our trade or add to our, or their, well-being. With all countries in Europe and Asia, our relations should be formal and correct. As individuals we may indulge in hate and love, but the Government of the United States embarks on stormy seas when it begins to love one power and hate another officially. Great Britain has never done it. She has paid Prussians to beat Frenchmen and helped Frenchmen to beat Prussians, without official love or hatred, save in wartime, and always in the interest of her security. The charge of perfidy hurled against Britain has been the charge of hypocrites living in glass houses while throwing bricks.

Not until some formidable European power comes into the western Atlantic, breathing the fire of aggression and conquest, need the United States become alarmed about the ups and downs of European conflicts, intrigues, aggressions, and wars. And this peril is slight at worst. To take on worries is to add useless burdens, to breed distempers at home, and to discover, in the course of time, how foolish and vain it all has been. The destiny of Europe and Asia has not been committed, under God, to the keeping of the United States; and only conceit, dreams of grandeur, vain imaginings, lust for power, or a desire to escape from our domestic perils and obligations could possibly make us suppose that Providence has appointed us his chosen people for the pacification of the earth.

And what should those who hold to such a continental policy for the United States say to the powers of Europe? They ought not to say: “Let Europe stew in its own juice; European statesmen are mere cunning intriguers; and we will have nothing to do with Europe.” A wiser and juster course would be to say: “We cannot and will not underwrite in advance any power or combination of powers; let them make as best they can the adjustments required by their immediate interests in Europe, Africa, and Asia, about which they know more and over which they have great force; no European power or combination of powers can count upon material aid from the United States while pursuing a course of power politics designed to bolster up its economic interests and its military dominance; in the nature of things American sympathy will be on the side of nations that practice self-government, liberty of opinion and person, and toleration and freedom of thought and inquiry—but the United States has had one war for democracy; the United States will not guarantee the present distribution of imperial domains in Africa and Asia; it will tolerate no attempt to conquer independent states in this hemisphere and make them imperial possessions; in all sincere undertakings to make economic adjustments, reduce armaments, and co-operate in specific cases of international utility and welfare that comport with our national interest, the United States will participate within the framework of its fundamental policy respecting this hemisphere; this much, nations of Europe, and may good fortune attend you.” …

American people are resolutely taking stock of their past follies. Forty years ago bright young men of tongue and pen told them they had an opportunity and responsibility to go forth and, after the manner of Rome and Britain, conquer, rule, and civilize backward peoples. And the same bright boys told them that all of this would “pay,” that it would find outlets for their “surpluses” of manufactures and farm produce. It did not. Twenty-two years ago American people were told that they were to make the world safe for democracy. They nobly responded. Before they got through they heard about the secret treaties by which the Allies divided the loot. They saw the Treaty of Versailles which distributed the spoils and made an impossible “peace.” What did they get out of the adventure? Wounds and deaths. The contempt of former associates—until the Americans were needed again in another war for democracy. A repudiation of debts. A huge bill of expenses. A false boom. A terrific crisis.

Those Americans who refuse to plunge blindly into the maelstrom of European and Asiatic politics are not defeatist or neurotic. They are giving evidence of sanity, not cowardice; of adult thinking as distinguished from infantilism. Experience has educated them and made them all the more determined to concentrate their energies on the making of a civilization within the circle of their continental domain. They do not propose to withdraw from the world, but they propose to deal with the world as it is and not as romantic propagandists picture it. They propose to deal with it in American terms, that is, in terms of national interest and security on this continent. Like their ancestors who made a revolution, built the Republic, and made it stick, they intend to preserve and defend the Republic, and under its shelter carry forward the work of employing their talents and resources in enriching American life. They know that this task will call for all the enlightened statesmanship, the constructive energy, and imaginative intelligence that the nation can command. America is not to be Rome or Britain. It is to be America.

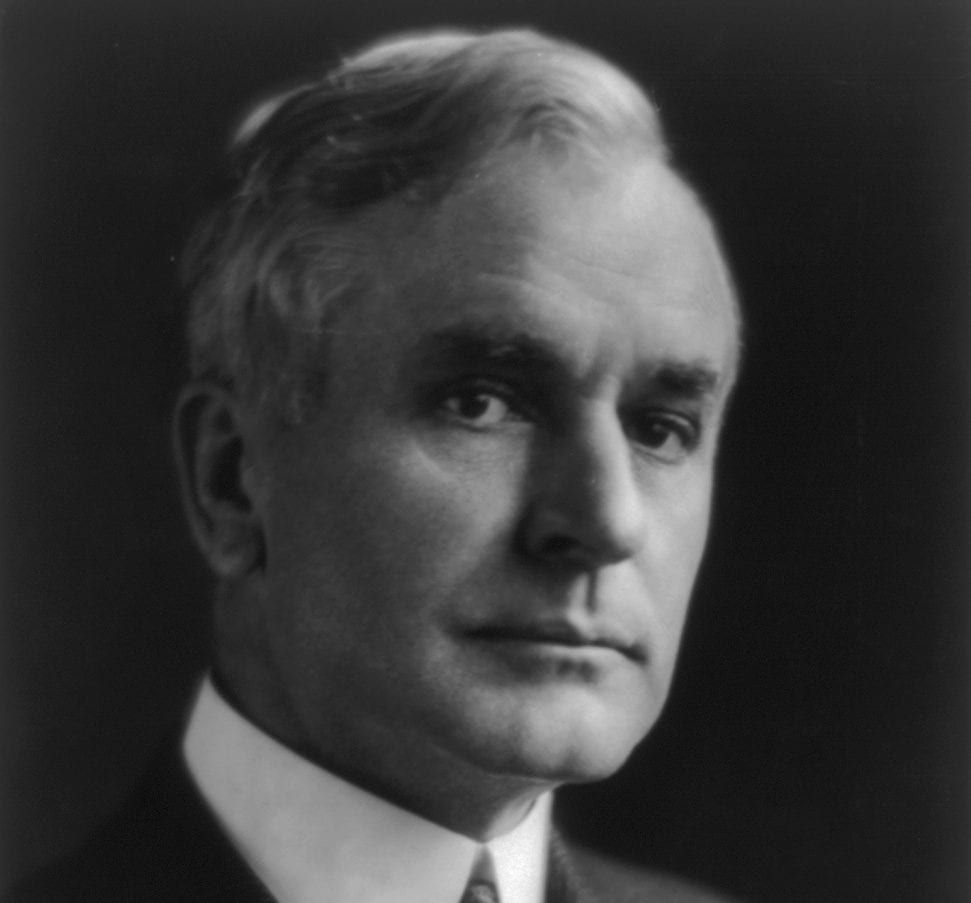

* Published by Macmillan and Co. Copyright 1939 by Charles A. Beard. Reprinted by permission. Charles A. Beard (1874:1948) is the author of numerous books on American history and foreign policy. He was the foremost American proponent of the economic interpretation of history.

A House of Many Mansions

January 20, 1940

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.