Introduction

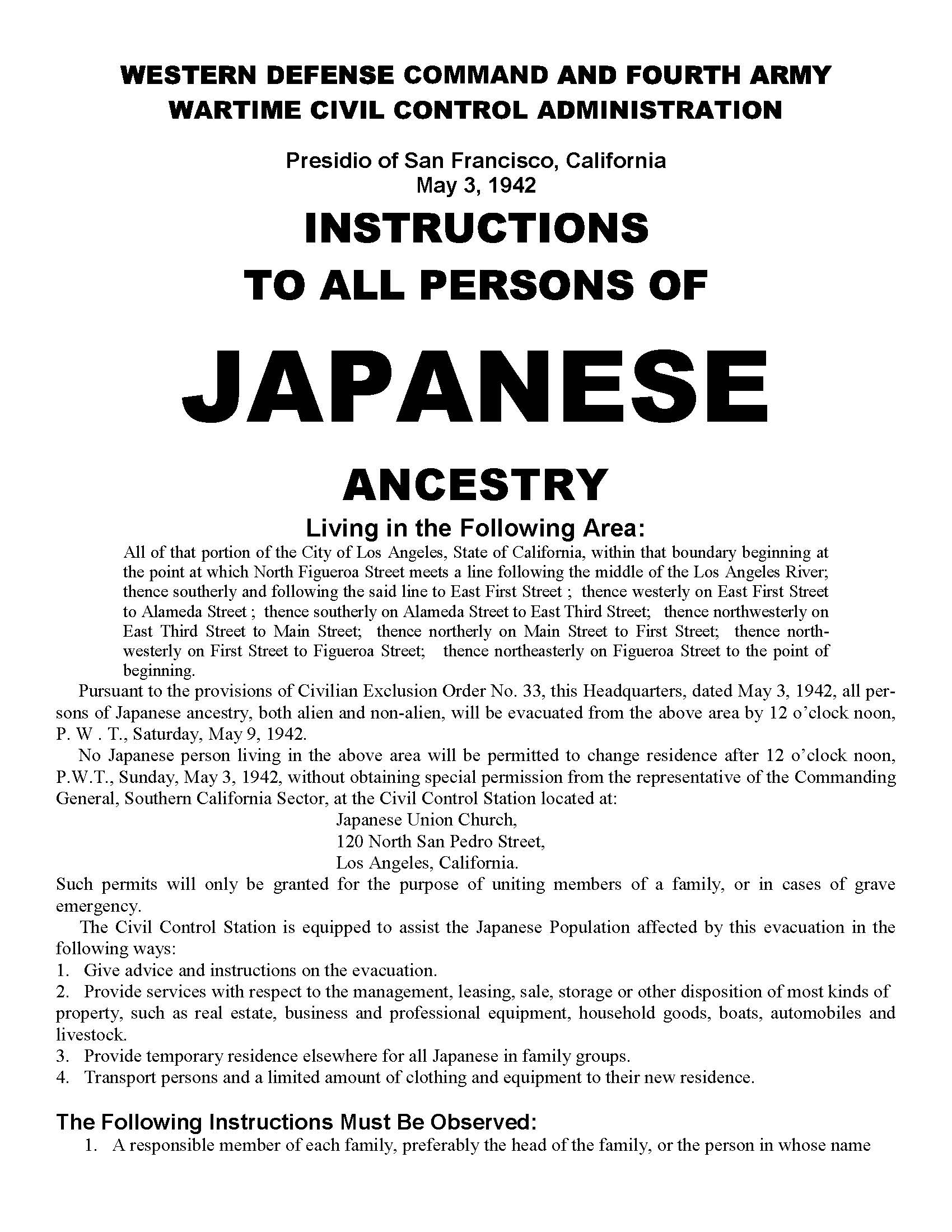

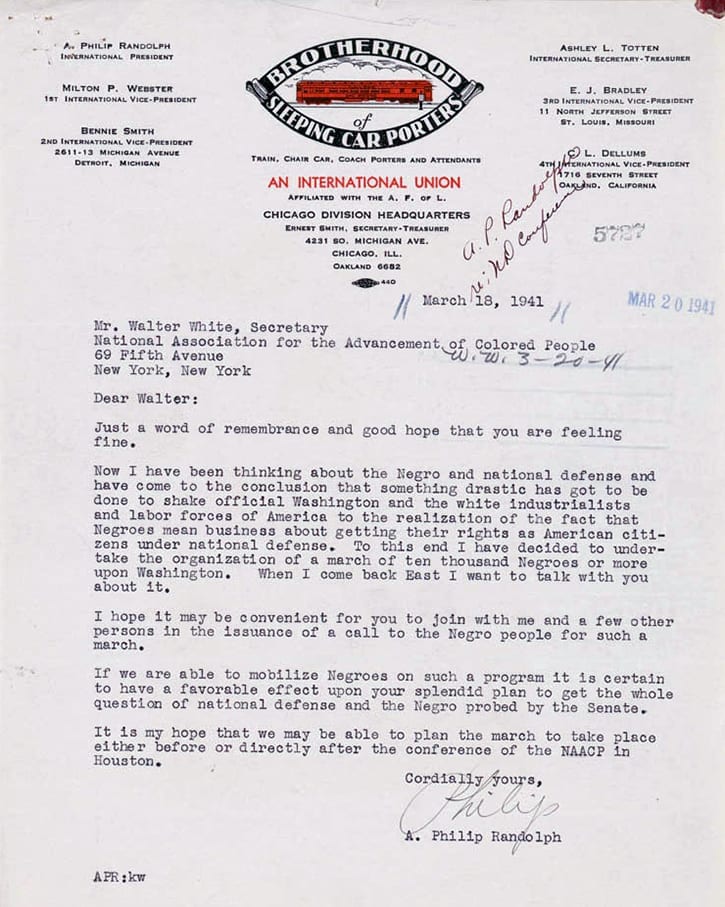

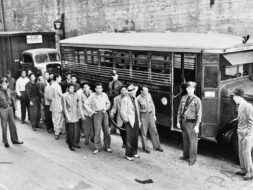

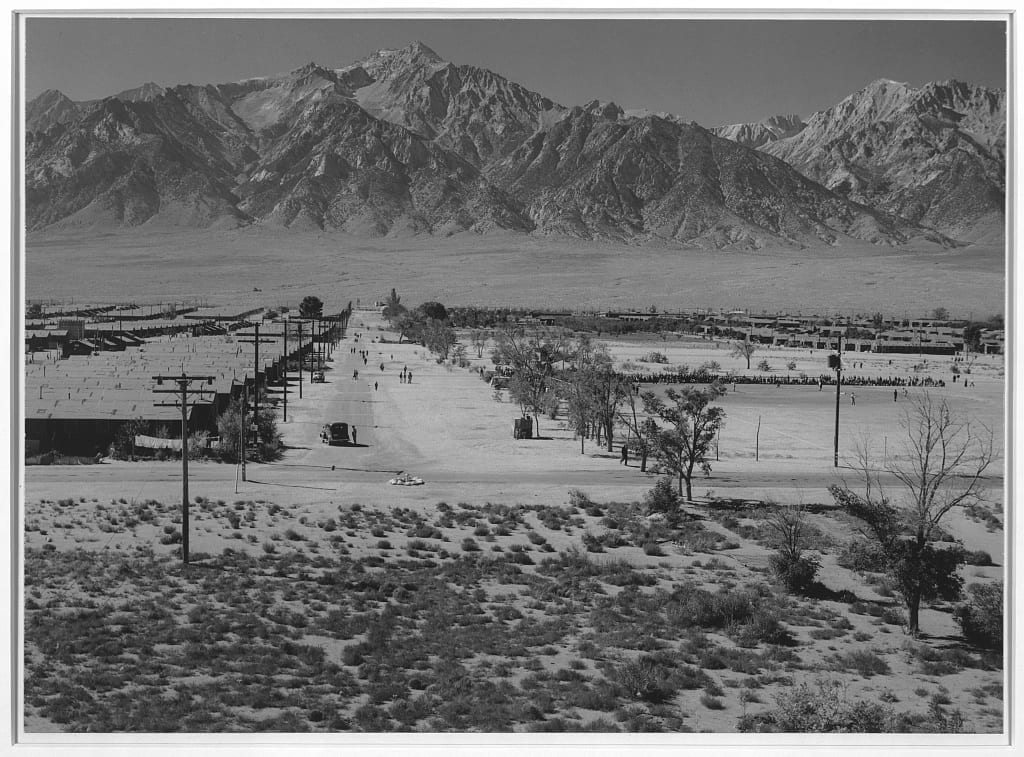

In 1943 the photographer Ansel Adams was granted limited access to Manzanar, a Japanese-American internment camp located in the foothills of the California Sierra-Nevada Mountains. He arrived just after a riot had rocked the camp and military authorities had administered a questionnaire to distinguish loyal from disloyal Japanese-Americans. Those inmates who answered questions incorrectly were deemed disloyal and shipped to another camp in Tule Lake. Japanese-Americans considered loyal were now allowed to leave the camp either by finding jobs, joining the military, or going to college.

To help re-assimilate Japanese-Americans into civilian life, Adams wanted to change public opinion so that communities would welcome rather than spurn these new arrivals. His photo essay, featuring 244 images with an accompanying narrative, had limited circulation during the war, however.

Source: Ansel Adams, Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese-Americans (NY: U.S. Camera, 1944), pp. 58-59; 63-67; 101. https://goo.gl/TNseGm.

In any group of society the children are of greatest importance, and this importance is accentuated under abnormal conditions. The evacuation made family life difficult in many ways; it created for children of impressionable age environmental problems that will be hard to eradicate. However, from the start, education has been of major concern to the authorities and to the parents. At Manzanar the older evacuees built a tiny park with rabbits, chickens, and ducks, so little children would know a duck when they saw one. There is a “Children’s Village” directed by Mr. Harry Haruto Matsumoto, where orphaned children from Alaska to San Diego find a home. Evacuation struck the very young and the very old. Newborn babies as well as the oldest persons were moved with all others. Kindergartens, grammar schools and high schools were established under the direction of Doctor Genevieve Carter of the Manzanar Educational Division. Hence there has been little interruption in the normal school life of the children, and the usual extra-curricular activities have not been neglected. The Manzanar High School is accredited to the University of California, even though its graduates are barred from that university by military restrictions. Plays, concerts, the Manzanar High School Choir under the able direction of Louis Frizzell, and a wide list of sports, keep the young people occupied and interested. The older residents play or are spectators at judo, kendo, tennis, basketball, football, and the universal enthusiasm – baseball. There is a golf links, unique in that there is no grass – only the desert earth. The greens are built up of sifted soil, and it all seems to work out satisfactorily, although there are certain difficult decisions to be made as to what constitutes “fairway” or “rough.” A new auditorium has been completed recently and movies, music, and drama are accented in the recreation program. There are no class or age distinctions at Manzanar, and toddlers will be seen sitting next to benign old gentlemen at an outdoor band concert, or thronging with their elders into an exhibit at the Visual Education Museum. Only those employed on the farms may pass beyond the confines of the Residential section, hence the emphasis on organized sport rather than on excursions and walking tours. Victory gardens and the Pleasure Park are the concern of groups who are able to work at them; the latter is an ambitious undertaking – pools, greenery, walks and a pavilion created in the barren soil of the desert within the confines of the Center. Under special permit trees and stones were brought many miles from the Sierra and set about with that persuasive informal formality of the traditional Japanese garden.

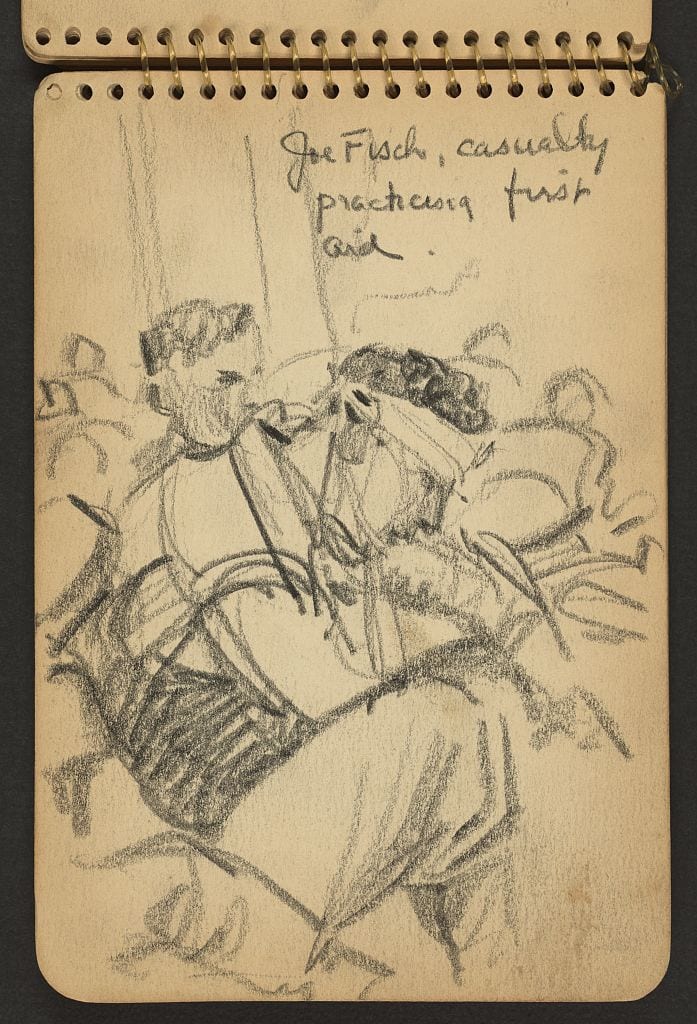

Another person associated with the Manzanar Hospital whom I would like to bring to your attention is Michael Koichi Yonemitsu, X-ray technician. Born in Los Angeles in 1915, he majored for three years in engineering, and hopes eventually to complete his studies and specialize in X-ray. Coming from an intelligent and well-to-do gamily and enjoying a secure life with an apparently clear and well-planned future before him, Michael Yonemitsu found the evacuation difficult to reconcile with his concept of American life. However, he has adjusted himself admirably to conditions beyond his control. He would like to see the future evidence a “return to sound economic levels, fair trade, and subsequent raising of world living standards; . . . a better understanding between all people to ease racial prejudice; and a move toward greater religious tolerances.” Speaking of the Japanese-American Combat Team he says, “My brother is in that combat team, I figure this is a chance to show his loyalty.”

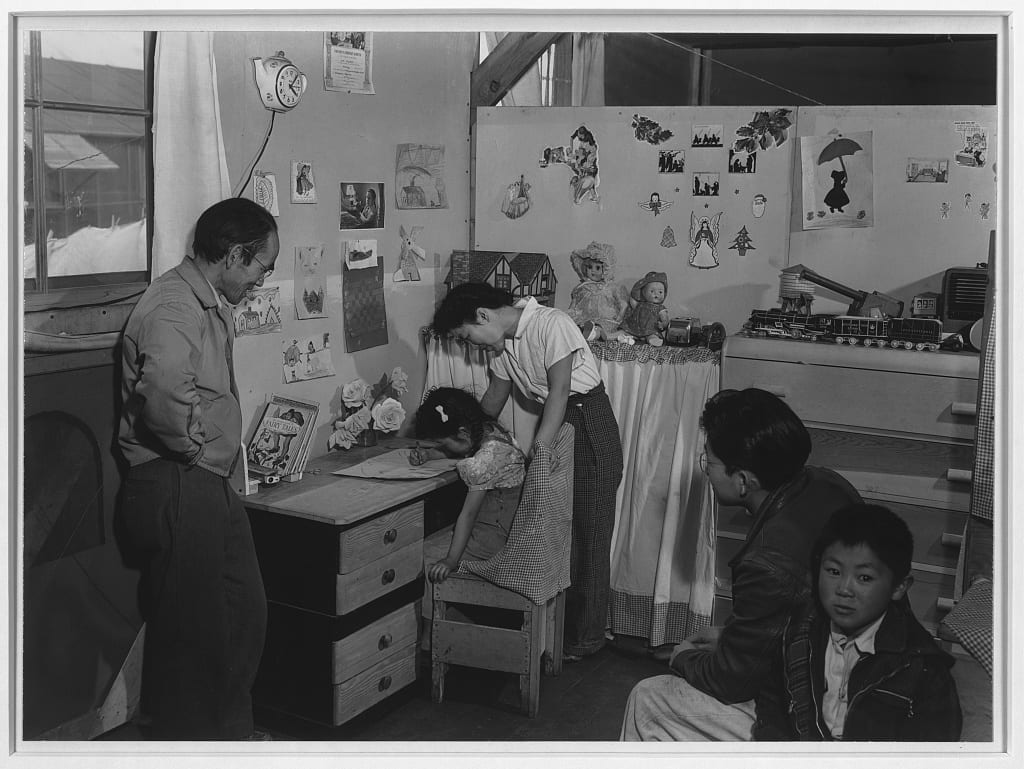

Visiting Michael’s home, we shall meet his father and sister. This home is perhaps fitted out a bit better than the average; there is a fine radio-phonograph, a good collection of classical recordings, and some simple modern chairs and bookcases. Through their sunny window they look out on orchards and the North Farm. Mr. Francis Yonemitsu, father of Michael, was born in Japan. He is not and cannot be a citizen. But he is American in spirit, and he is a realist. In regard to his pre-war life in America he said he would have liked to be truly assimilated, but that the Caucasians themselves prevented it. He was automatically barred from many public places. As to the future he says, “At present I am undecided. I leave my children’s plans up to them. They are citizens; my problem is far more difficult.” Mr. Yonemitsu hopes that in the post-war world “our federal government will take steps to smooth out once and for all the minority problems of the Japanese, Negroes, etc. . . . Religion is valuable and we should attempt to further religion. Faith should be the guiding factor in our lives.” (The Yonemitsu family is Catholic.)

On top of their phonograph I found a picture of Our Saviour, a photograph of Robert Yonemitsu in the uniform of an American soldier, and some of his letters to his sister Lucy. I photographed them just as they were. The picture tells much about the Yonemitsu family, and about many other such families as well. Father Yonemitsu says about the combat team: “My son Robert is in the combat team. I am hoping he will be a credit to me and to the Japanese-American people. I hope he will help to show that the Americans of Japanese ancestry are as loyal as any other Americans.”

Conclusion

Perhaps we find it difficult to visualize the life and mental attitudes of the evacuees. We are, in the main, protected and established in security considerably above other peoples. We take Americanism for granted; only when civil duties such as military service, jury duty, or the irksome payment of taxes, confront us do we sense the existence of government and authority. We go through conventional gestures of patriotism, discuss the Constitution with casual conviction, contradict our principles with the distortions of race prejudices and class distinctions, and otherwise escape the implications of our civilization. America will take care of us, America is as stable as the mountains, as severely eternal as the ocean and the sky! In times of war we sacrifice magnificently; in times of peace we prey upon one another with sincerity and determination. The world has seldom seen our superior in intellect and accomplishment, nor has it seen our inferior in many aspects of human relationships. Only when our foundations are shaken, our lives distorted by some great catastrophe, do we become aware of the potentials of our system and our government.

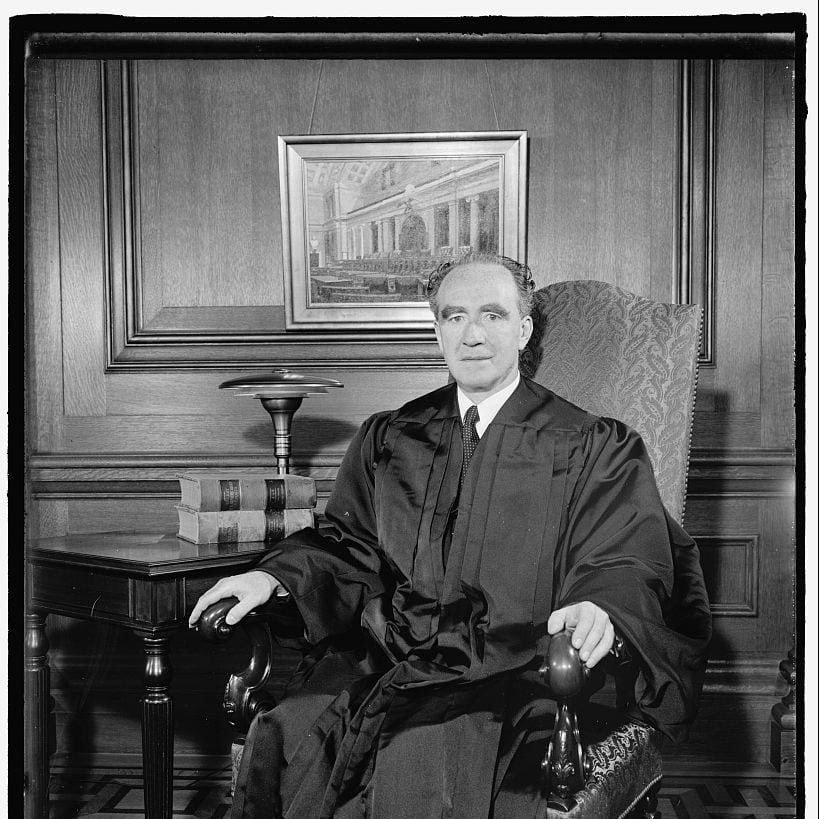

- 1. In Ozawa v. United States (1922), the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the ban on Asian immigrants becoming citizens because they were not “free white persons,” as required by the Nationality Act of 1790.

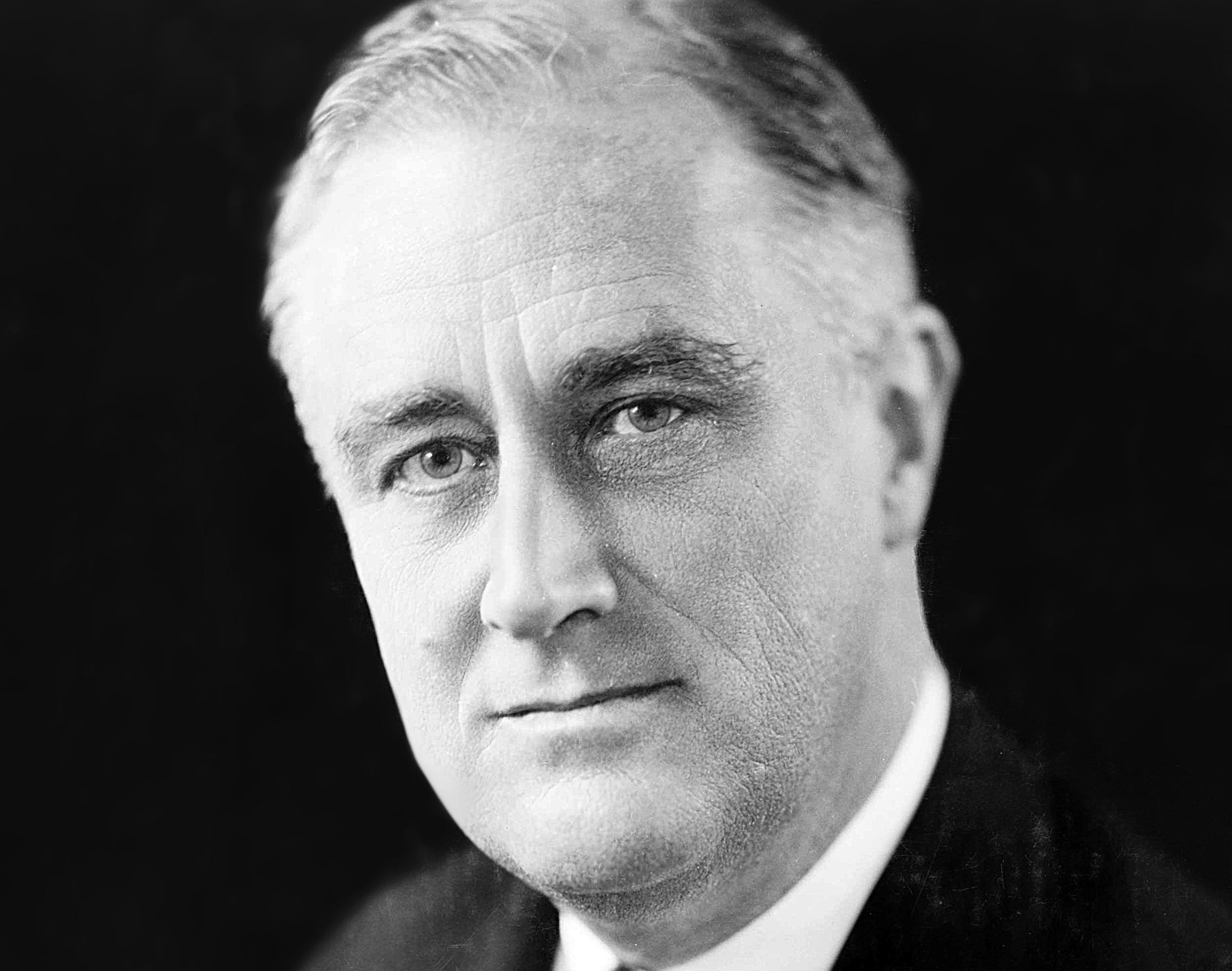

Annual Message to Congress (1945)

January 06, 1945

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.