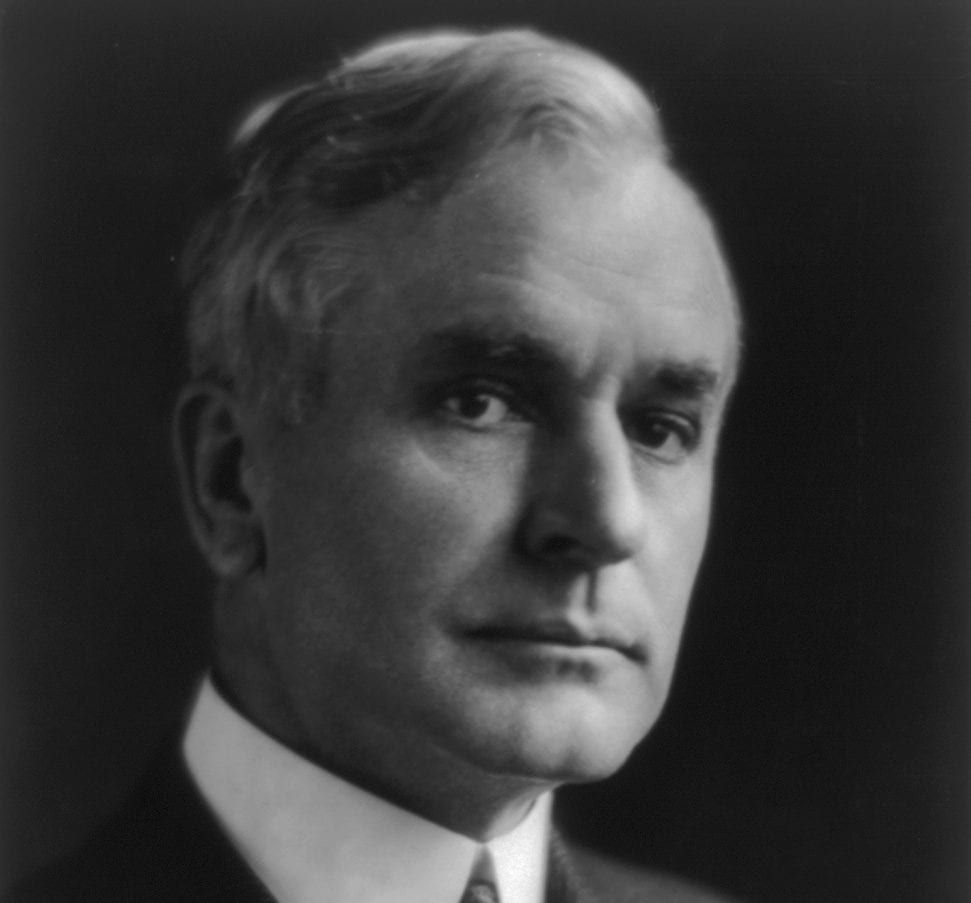

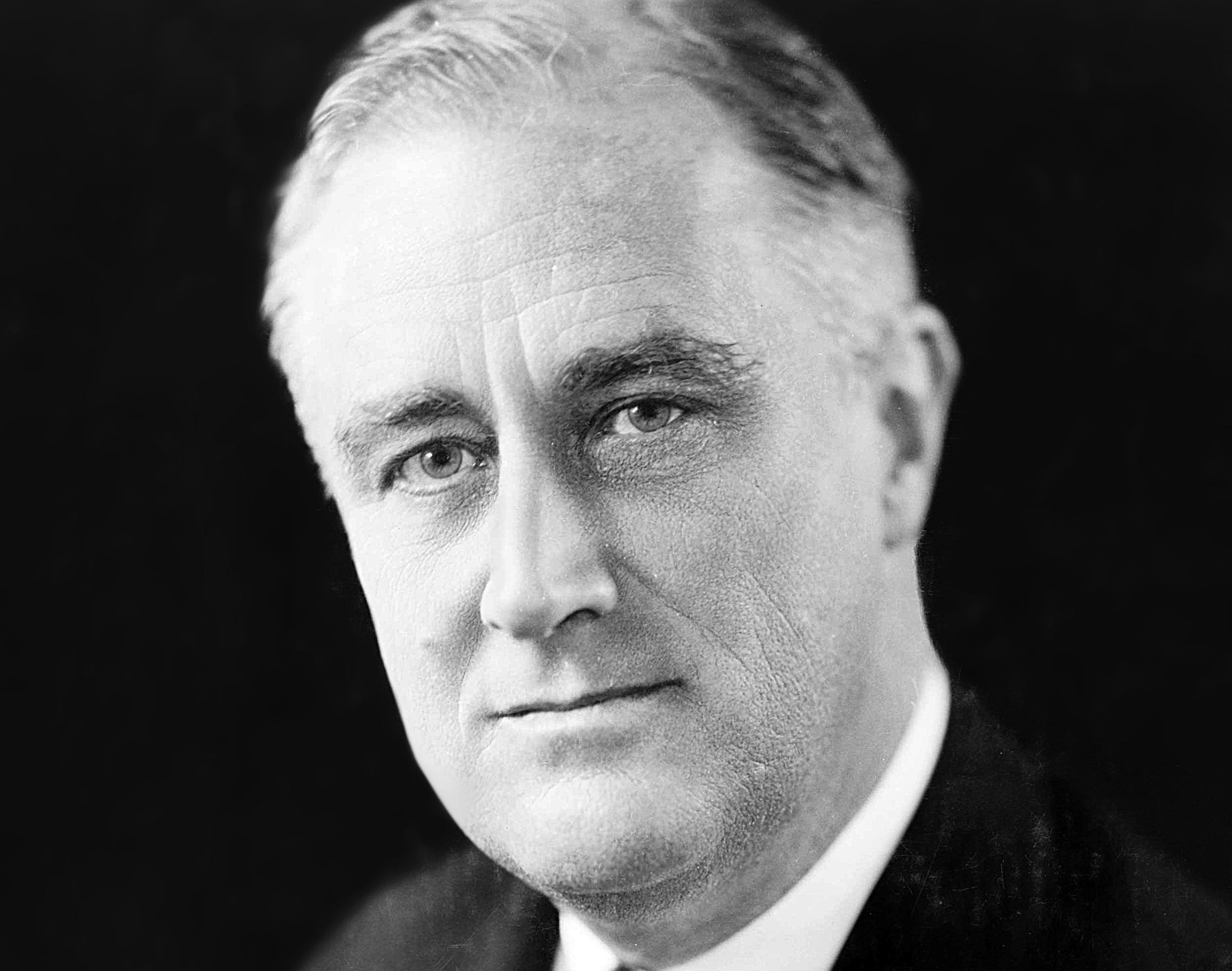

Shortly after I came home from London I spoke over the radio for the re-election of President Roosevelt. I declared then that my sincere judgment was that we ought to stay out of war—that we could stay out of war. I urged that we give England all possible aid. I feel the same way about it today.

Since then there have appeared many false statements regarding my views on foreign policy. Moreover, there is a growing confusion and a reliance upon emotion which strikes me as altogether unnecessary and extremely harmful.

Tonight I hope to set forth as clearly as possible my views on some phases of the great issue confronting the American people. It is my earnest desire that I may be of some assistance in helping my fellow-citizens to form a clearer understanding of the burning issue of our foreign policy.

The saddest feature of recent months is the growth of intolerance. Honest men’s motives are being attacked. Many Americans, including myself, have been subjected to deliberate smear campaigns merely because we differed from an articulate minority. A few ruthless and irresponsible Washington columnists have claimed for themselves the right to speak for the nation. The reputation of the American press for fairness is being compromised by the tactics of these men.

SEES PERIL IN SMEARS

This habit of smearing an opponent because you disagree with what he stands for is a distinct menace to our free institutions. How can we maintain national unity when the motives of patriotic men are indiscriminately assailed? Intolerance breeds intolerance, and the whole country suffers. No matter who wins this war, America faces most critical times. If at this early date intolerance of contrary opinions flourishes, our future is dark indeed.

A favorite device of an aggressive minority is to call any American questioning the likelihood of a British victory an “Apostle of Gloom”—a defeatist. I always believed that when the American people sent an Ambassador to a foreign country they expected him to report the facts to his government as he saw them, the bright side and the dark side—the good things and the bad things—the strengths and the weaknesses. I never thought that it was my function to report pleasant stories that were not true. Every one will agree that had I as your Ambassador reported to our government anything but the truth as I saw it, I would have been false to my trust—I would have betrayed my country.

When I repotted to our government the seriousness of the problems that faced the British people I did it in considerable detail, and purposely, because I wanted our government to have all the information possible affecting the plight of Great Britian so that this country in the days to come could guide itself more intelligently in its foreign policy regardless of what the outcome of the war might be.

DENIES PREDICTING BRITISH DEFEAT

As support for the charge that I am an apostle of gloom, it is said that I have predicted the defeat of Great Britain. That statement is not true. I am aware of and have reported on the serious obstacles to British victory. I know many of Britain’s weaknesses, but a prediction can be based only on a complete knowledge, knowledge of the strength and weaknesses of both sides.

There are many phenomena in this war which defy explanation even by the most expert. If the Germain Air Force can practically destroy a city in a one-night raid, as in Coventry, why is that it has failed to wipe out industrial England in a series of these raids? If, as we know, England can live only if her ports remain open, why has not the German Air Force concentrated its efforts on closing these ports by aerial bombardment? It has made but few raids on Liver-pool and Bristol and those only recently. What is the answer? I don’t know. Apparently no one does.

The morale of the British nation defies description. It is as fine a display of human courage as has ever been witnessed. But what do we know about the morale of the German Army or of the German people? Have they this quality of toughness or are they brittle after eight years of tyranny? These are but a few of the unknown elements which may well determine the final outcome. Thus a prediction now of England’s defeat would be senseless. One can recognize the enormous difficulties facing Britain without foreseeing its defeat.

WANTS NO DICTATOR DEAL

Another label used as a smear against certain citizens who favor keeping America out of the war is the word “appeaser.” I have been called one. Here is my answer. If by that word, now possessed of hateful implications, it is charged that I advocate a deal with the dictators contrary to the British desires, or that I advocate placing any trust or confidence in their promises, the charge is false and malicious. The word of these tyrants has been shown to be worthless. They themselves proclaim that their promises are sham.

But, if I am called an appeaser because I oppose the entrance of this country into the present war, I cheerfully plead guilty. So must every one of you who wants to keep America out of war.

The term “warmonger” is another example of this unfortunate trend. Such a charge does not help us in deciding what is best for our country. We ought to be done with this sort of stuff which only confuses and divides. We ought to give a fair hearing to all sides. In that way we will be right and united.

This smear campaign is particularly violent against many of our citizens who desire this country’s influence to be used in an effort to bring about a just and lasting peace. These men feel that we are already on a toboggan ride toward involvement in the European war. They believe that as long as this war continues there is the ever-increasing possibility—yes, probability—that we ourselves will become involved, bringing ruin to our civilization and an end to our democratic form of life. We cannot blame these men for working for peace. Such an impulse springs from the oldest and most constant of man’s desires.

Of course, it is only too true that a just peace at this time does not appear to be in the cards. Hitler, the man who wanted war, has slammed the door on peace. To all the world he has proclaimed that he, Hitler, wages total war for a new world order—a new world where our society of justice according to law cannot even exist.

Realizing therefore that we cannot hope for a just peace in the near future, let us consider what should be America’s policy.

Since my return home what has impressed me most is the growing conflict in the minds of the American people over the two courses of action which the vast majority of Americans advocate—that is aiding Britain and staying out of war. Nearly all the American people want to aid Britain and practically all of the same people want to stay out of war. But they are beginning to feel that these policies may prove inconsistent. When they try to reconcile them in their own minds they become confused. If one emphasizes aid to Britain he thereby risks entering the war. If, on the other hand, he emphasizes avoidance of war he minimizes the aid to Britain. I think that these policies can be applied without confusion and without risk of contradiction. We need but apply the test which should motivate every one of us. Whenever the issue is raised, whether for the President, the Congress, the Army or the Navy, the test for any proposal should be—what is best for the United States of America.

In considering what is best for the United States, let us look at the problem of aid to Britain. I favor now, as I did in my talk for the President, that we give the utmost aid to England. By so doing we will be assisting a nation which the American people want to see win. But, more than that, by helping Britain we will be securing for ourselves the most precious commodity we need—time—time to rearm.

If, and God forbid, England were to be defeated quickly and the Germans succeed to the British Navy, this country now is not prepared to defend its own shores, let alone the North American Continent.

It is true that we are awake at last and we are preparing. In this modern war, where industry is more vital than man-power, an awakened America can speedily make its gigantic power felt by all the world. England’s spirited defense is affording us precious time for rearming. It is consequently to our interest that England be aided in her courageous battle.

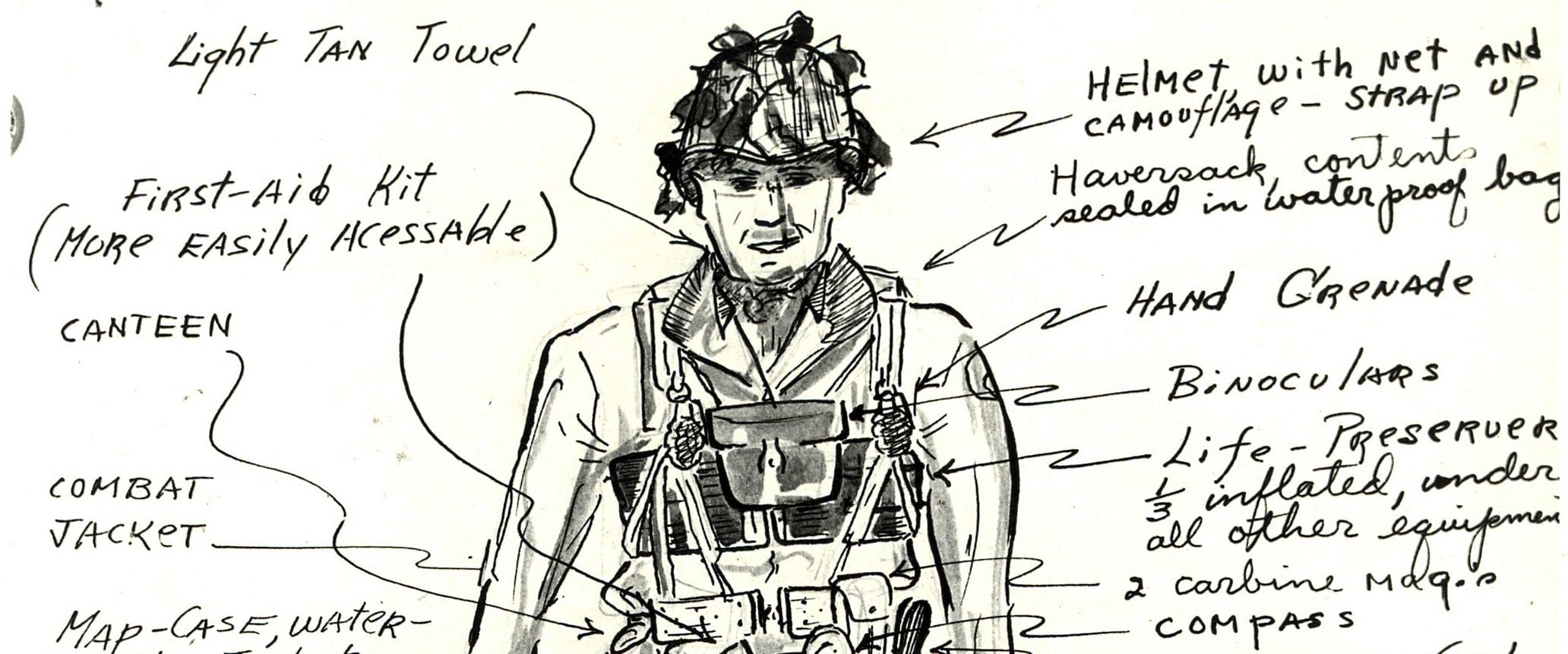

No one will seriously urge that we should give beyond the absolute minimum requirement for our own protection. Where that line is to be drawn is to be determined by the President acting with our trained experts of the Army and Navy. They know best what we can spare. The American people have confidence in them and will trust their judgment. They have taken an oath to defend this country, and that means defend it against all aggressors. However, because in addition to wanting to aid Britain the American people want to stay out of war, this aid should not and must not go to the point where war becomes inevitable.

So far as financing the assistance we give to Great Britain is concerned, my personal opinion is that the British ought to make available to us all the assets we can use. If, after the resources of Great Britain were used up, it were still sound American policy to assist them, I would prefer that it be done through outright gifts, since I would not expect that loans could be repaid.

Under our policy we can give them guns; we can give them ammunition; we can give them airplanes; we can give them everything that doesn’t make war inevitable. Because aid to England is part of a constructive American policy to safeguard America, we should go to the very limit in our assistance, but not to a point which would endanger our own protection.

WAR DECLARATION “OUTMODED”

Many Americans fear that Hitler will declare war on us if we continue to aid Great Britain. To declare a state of war is a bit outmoded in these days of unbridled force. Don’t forget that Hitler will declare war an this country, or will make an attack, only when he thinks that such action is for his best interests. This country certainly has committed acts sufficiently unneutral to justify a less despotic tyrant than Hitler to declare war, The American people obviously have not the slightest desire to remain neutral in the face of the aggression of the Axis powers.

It is not surprising that we desire Hitler’s defeat. The English are defending a society which respects law and which upholds the dignity of the individual. All of us want very much to see destroyed once and for all the attempted decivilization of the world in the name of Nazi pagan philosophy.

Despite the growing hysteria, despite all the clamor and the shouting, despite all the charges and counter-charges, the various groups in America are not far apart. Only a very few Americans want to go to war, I respect their sincerity, but I prefer the judgment of the great majority who believe that to go to war is not for our best interests.

Who really wants war? Certainly the isolationists (with whom I cannot sympathize) do not want war. The President has declared on many occasions that he does not want war. Congress surely is dedicated to the task of keeping us at peace. Why, then, all the shouting?

Perhaps it is due to a certain fatalistic attitude, lately noticeable, to the effect that no matter what we do we are bound to be drawn into the war as an active combatant. The people who have lost hope for peace in America, I say, are the real defeatists. With such a position I flatly disagree. Unless we are attacked, the American people do not have to go to war. They will not go to war if they will stay out of war. There will be no American intervention while there continues to be free and open discussion, while the people know all the facts, and while our system of popular government functions.

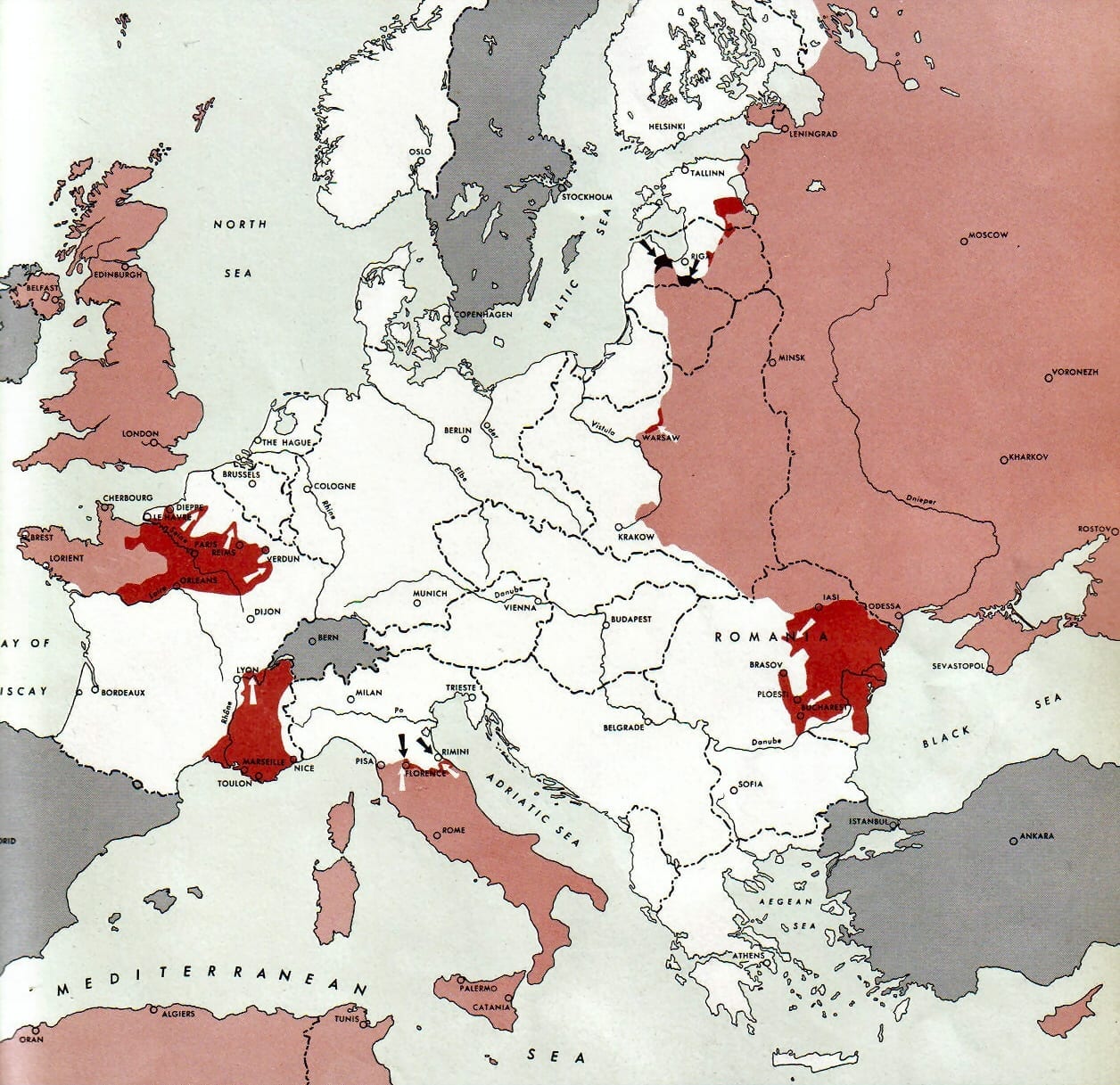

There are those who say if we stay out and Hitler wins we will be subject to a military attack by a combination of the totalitarian powers. On this question of a threatened invasion of our country, I said in my speech favoring the re-election of President Roosevelt that I had been a witness to a small but brave air force holding at bay an overwhelmingly superior air armada and preventing an invasion over but twenty miles of water.

RECALLS PLIGHT OF BRITISH

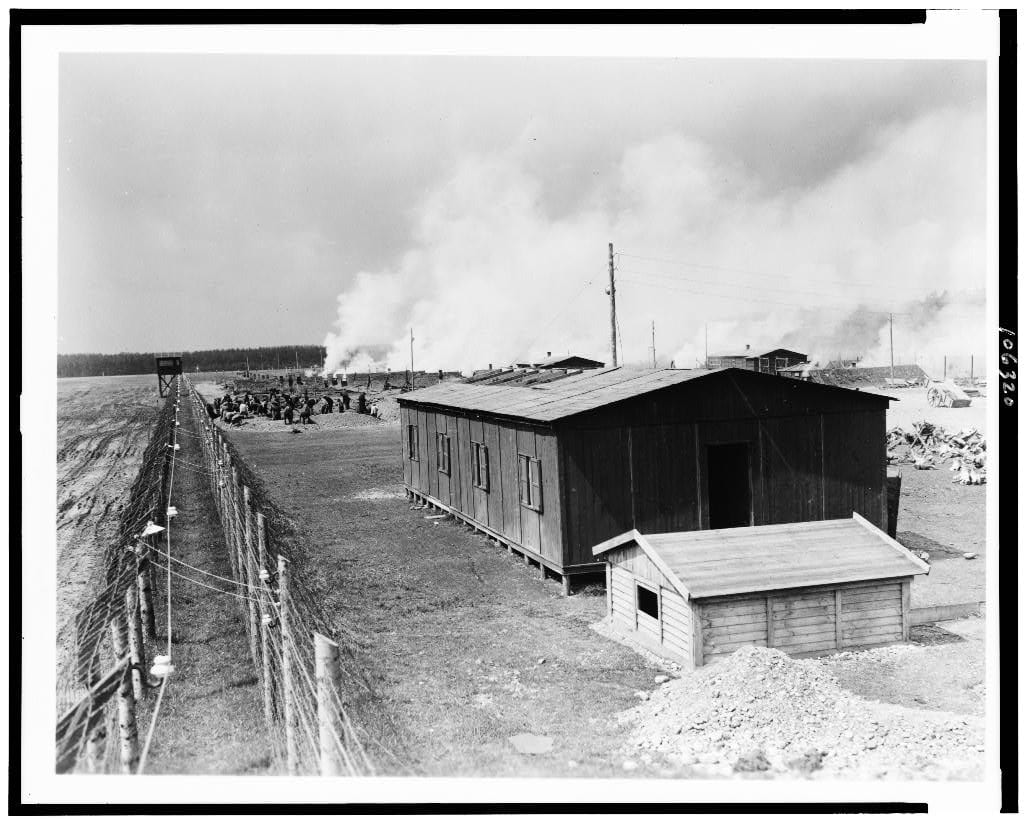

After the fall of France and the retreat of Dunkirk the English defenses were in a deplorable state. Vast quantities of arms and ammunition had been destroyed and captured. Only a miracle had rescued the British Army. Even hunting rifles were being collected in England in order to equip part of their lighting forces.

In spite of such handicaps, and in spite of the fact that the conquest of the British Isles would have given Hitler domination of Europe, the Germans have never been able to secure a foothold on that island.

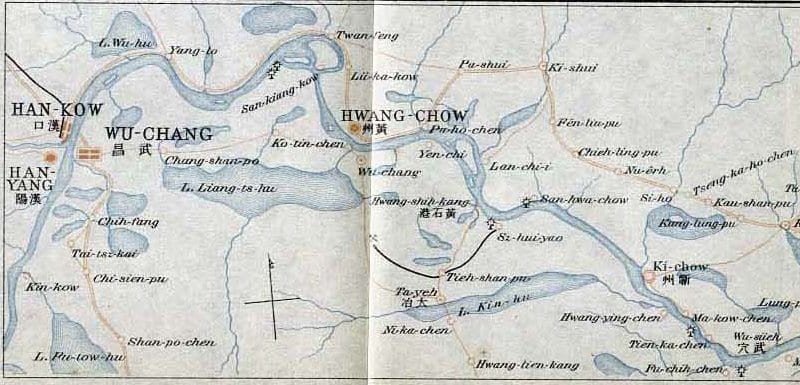

Consider what it means to transport troops and ammunition over 3,000 miles of storm tossed ocean; consider what risks are involved in seeking to pierce naval and air defenses. What would our enemies use as bases for their planes, what as bases for their shipping? I have read that Dakar in Africa is only five or six hours by plane to the most easterly point of South America.

But I am assuming that our policy with the other Americas will guarantee mutual protection. But suppose a foreign power, by guile, coercion or subversive activities, should secure the support of any of the countries in this hemisphere. We certainly have a right to expect that in their own self-interest the other countries of this hemisphere will, through diplomacy or force or both, insist that the principle of the Monroe Doctrine be maintained.

And, mind you, even after an enemy had flown across an ocean, it would be faced with the problem of maintaining its forces and supplies large enough to cope with the resources of the North American Continent, which would speedily be brought to bear against them. Remember that the experience in this war to date indicates that ships, even though protected with naval strength, face severe handicaps in seeking to land in the face of an attacking air force operated from a land base. Reports from the Mediterranean seem to support this contention.

Moreover, it is still very difficult to transport many tanks or many pieces of heavy ammunition in airplanes. I hope, therefore, that I am not too cheerful or too optimistic when I express confidence that we in America can successfully defend ourselves, assuming we avail ourselves of the opportunity to make ourselves strong.

JUSTIFIES OUR CONFIDENCE

And why shouldn’t we have such confidence in ourselves? After all, we are a country of 130 million people with a great record for vigor, ingenuity and bravery. For the life of me, I cannot understand why the tale of a great military machine 3.000 miles away should make us fear for our security. Let America devote its energies to armaments—those energies which have heretofore followed peaceful pursuits—and I have little doubt that we can be secure against any power or group of powers in the wide world.

Another point frequently stressed in debates about our foreign policy is that if the Germans win, the totalitarian system will ruin us economically. Let me state, first of all, that I believe that with the declaration of war on Sept. 3, 1939, America’s economy entered an acute phase. I opposed the war because I believed that the day Europe went to war, regardless of whether we ever participated, our problems from that minute on became critical.

I quite agree that if England were to win this war we would be a great deal better off than we would be if England lost. There is no argument on that score. The point of argument, however, is on the question of whether to help England win the war we should get into the war ourselves, thus exhausting our own resources so as to threaten our whole civilization,

Frankly, if I could be assured that America, unprepared as she now is, could by declaring war on Germany within the space of say a year end the threat of German domination, I would be in favor of declaring war right now.

The inescapable point, however, is that we are not prepared to fight a war—even a defensive one—at the moment, let alone an offensive one. Furthermore, could any one make a safe prediction that the war would be ended in a year, or even two, with what help we would be able to send?

As I said in my speech for the President, I cannot see where we could get the ships to carry the necessary army and equipment for our participation in the war. Further than that, I really don’t know where our Army would go if we started off to fight a war. Just as I regard it impossible for a foreign power to invade this country, so do I regard it impossible for us to invade Europe,

CONTRASTS STRENGTH OF ARMIES

The British say that they have approximately one and one-half million soldiers under arms. Assuming that all those men could be used in an attempt to invade Europe and were not necessary for the protection of the Mediterranean or their own island home, I fail to see by what process the six million Germans under arms would be overwhelmed. It certainly can’t be lurking in the minds of even the most rabid interventionists that we could send into this kind of a war a sufficiently large expeditionary force to make up for the disproportion between the German and the English military forces.

There are those who say, “Ah, but we can go to war and yet not use our man power.” This sounds feasible today. Would it be feasible six months hence? I do not believe it. To me we are either all the way in the war or all the way out of it. Even if it appears to be feasible today, let us not forget that never in the history of mankind have events taken place with such lightning speed.

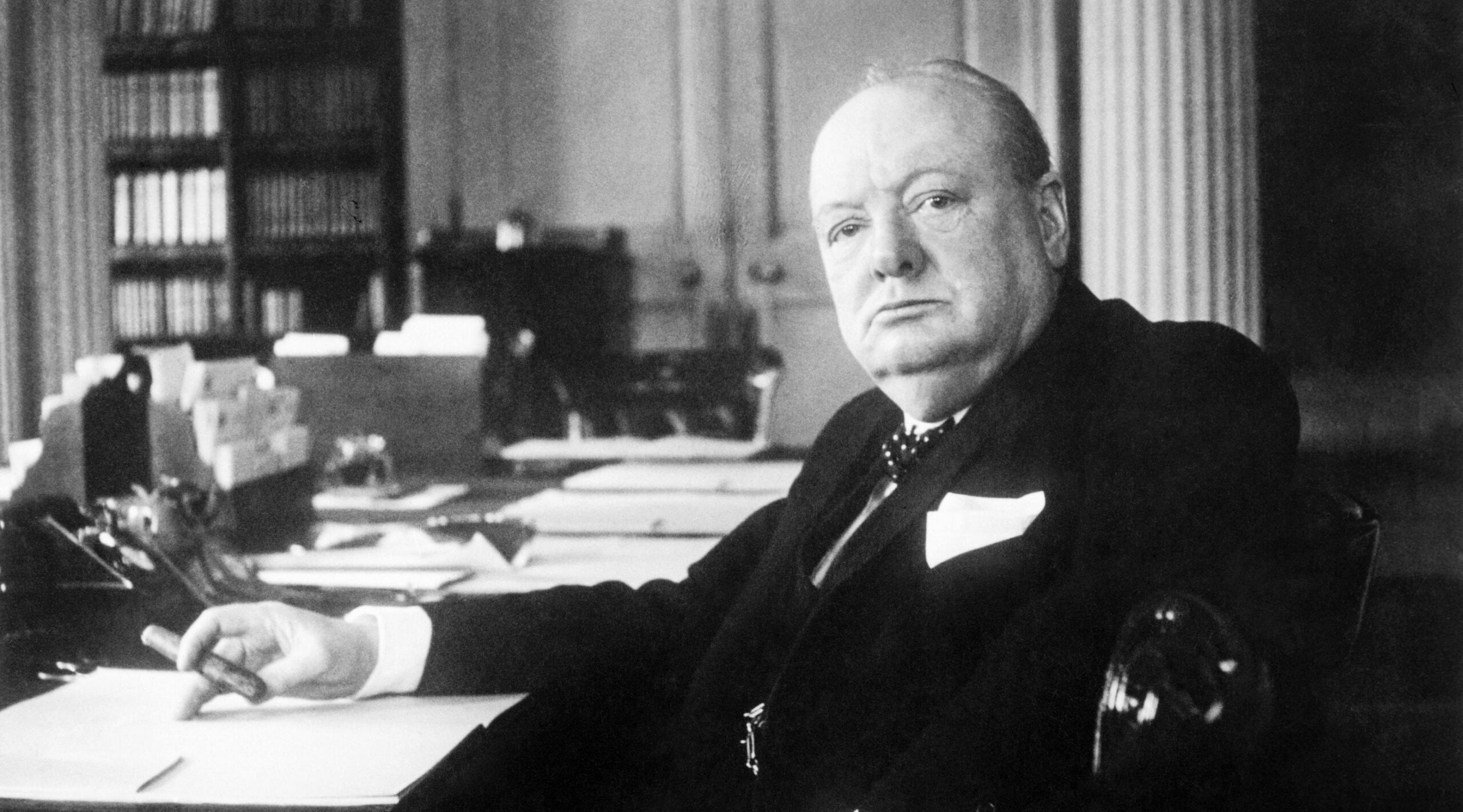

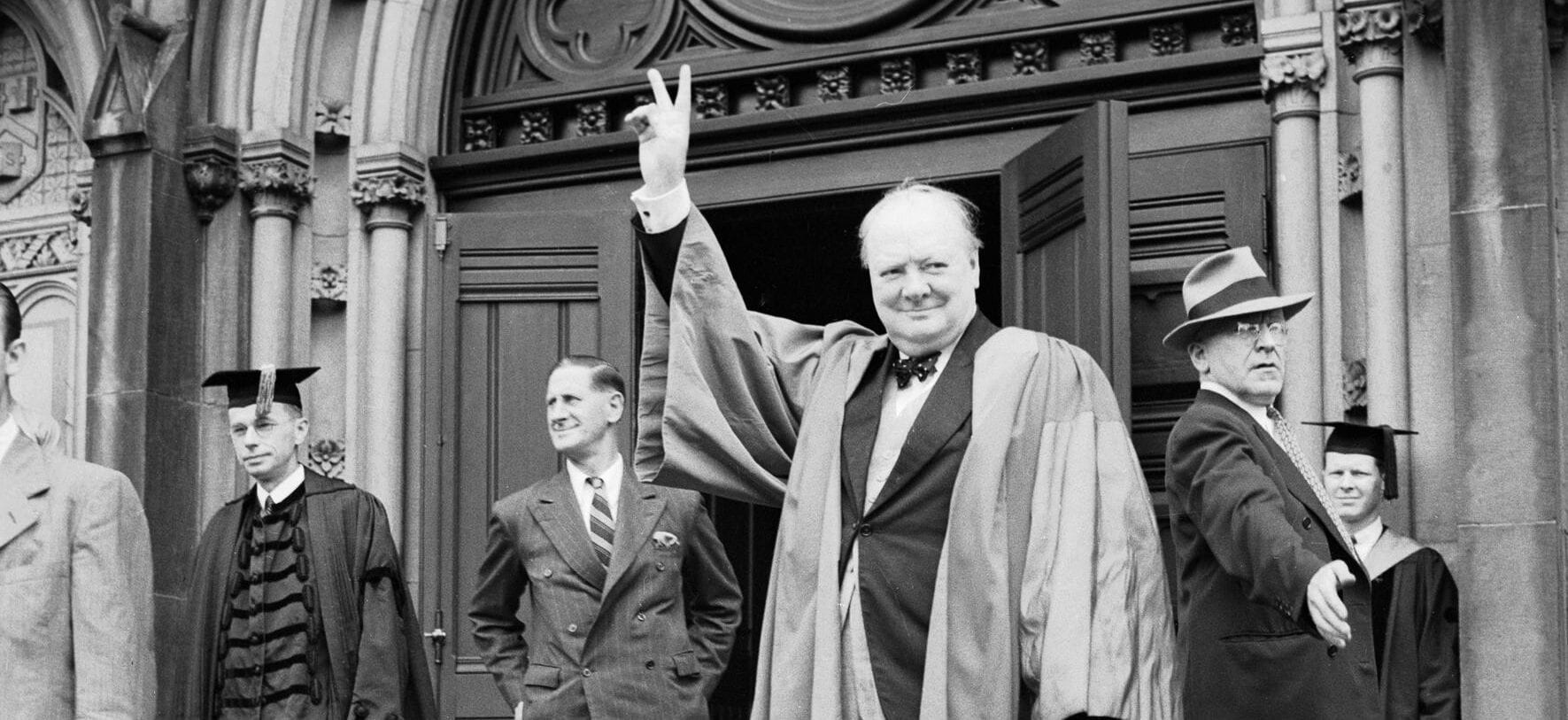

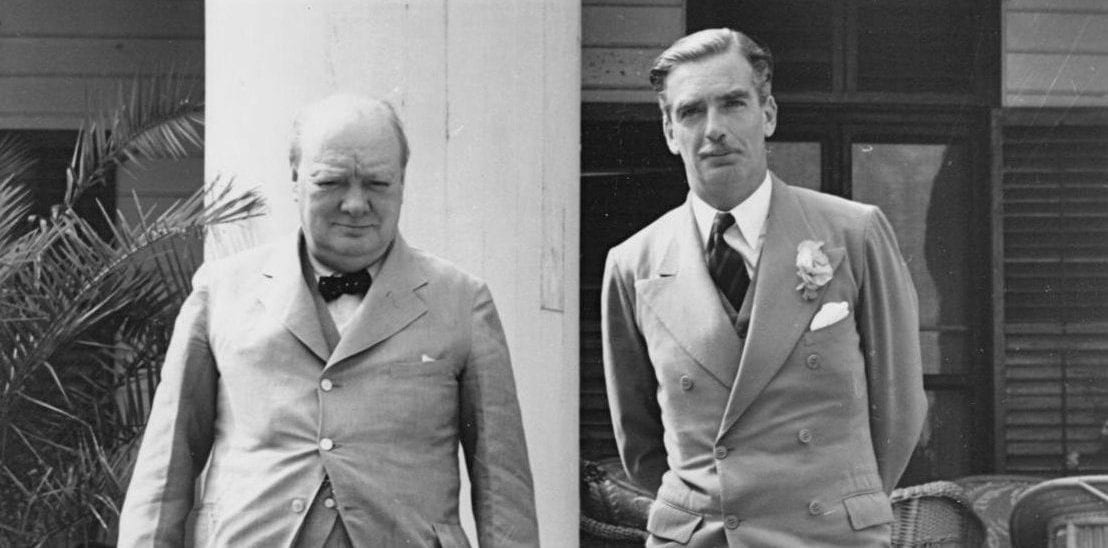

Last February some were calling it a “phony” war. In May the Germans struck. In sixty days Hitler had conquered a large part of Europe. If we go to war our man power cannot be preserved from battle. Only yesterday Mr. Churchill said, “We do not require in 1941 large armies from overseas.” Does that mean our boys are expected over there in 1942?

What would be our war aims? We have not had any debate on that score. We certainly are not going into the war just to underwrite the war aims of another country without knowing what they are. Germany under Hitler has no war aims except to dominate the world. She probably could not turn back now if she desired. England is, of course, fighting for her existence, but already we hear dissatisfaction that the aims of the British nation in this total war have not been set forth. Are we to sign a blank check? Common sense would seem to require that there be the most complete clarification of American aims in this conflict before we take the fatal step.

Some use the argument that should the Axis powers prevail they would inevitably impose on America a totalitarian regime. They therefore argue that we should go to war to prevent this. But have they considered that by becoming involved in a war they may lose the very thing for which they are fighting? How long could a democracy last while trying to fight a long drawn-out war?

BRITISH LEADER IS QUOTED

As Arthur Greenwood, the British labor leader, speaking in a debate at the Oxford Union, said: “If this war is fought to exhaustion, we will experience the like of which Britain has never seen. And we will find at the end of the road of all our bloodshed and suffering—not a democracy, but an authoritarian regime of the right or of the left.” But we here in America do not want a dictatorship of either the right or the left. We want to preserve our democracy. And, ladies and gentlemen, we are not going to preserve anything by getting into this war.

It is said that we cannot exist in a world where totalitarianism rules. I grant you it is a terrible future to con-template. But why should any one think that our getting into a war would preserve our ideals, a war which would then practically leave Russia alone outside the war area getting stronger while the rest of the world approached exhaustion?

Suppose we go in and the war continues for two or three years. We will be paying the whole bill—make no mistake about that. Does any one in his right mind think that the world won’t be completely bankrupt? Mind you, even now we are supporting China financially and we have already made available $100,000,000 to South America to aid her economy.

Well, at the end of the war we win—so what? What is the status of the world? Who is going to reorganize Europe? England and the United States? But we are then in a bad way and we must contemplate great internal problems of our own. Our taxes will be high; more people will be paying them; our national debt will be enormous; we will have an Army to demobilize; we will have to readjust a whole nation, agricultural as well as industrial, in the transition from a war basis to a peace basis. England will have the same conditions.

Yet, to keep defeated Germany and the other countries from going completely communistic we will have to reorganize them as well as ourselves, probably standing guard while this reorganization is taking place. I shudder to contemplate it. Are our children’s and our granchildren’s lives to be spent standing guard in Europe while heaven knows what happens in America?

Another argument we hear is that it is our duty to go to war because England is fighting our battle. England is not fighting our battle. This is not our war. We were not consulted when it began. We had no veto power over its continuance. England’s own leaders have told us why they are fighting. They are fighting for their very existence.

It does happen that England’s spirited defense is greatly to our advantage. It is true—she is waging a war against a force which seeks to destroy the rule of conscience and reason, a force that proclaims its hostility to law, to family life, even to religion itself. Therefore we ought to arm to the teeth and give as much help as we can to Britain. But let us do it on the basis of preserving American ideals and interests. But make no mistake, let no nation think that because the American people do not want war they will not go to war should their own vital interests be at stake.

PRESIDENT’S AUTHORITY CITED

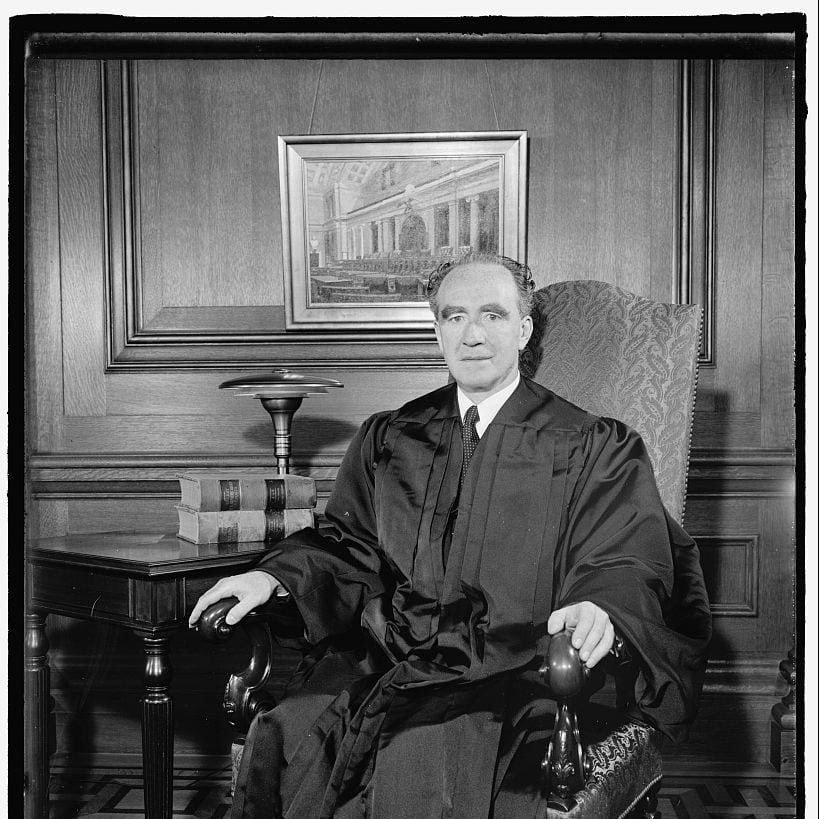

One hears the argument that if war is declared the President will secure powers needed for our defense. The President has very wide authority under existing law. Congress, I feel certain, will give him all the power that the protection of American interests require.

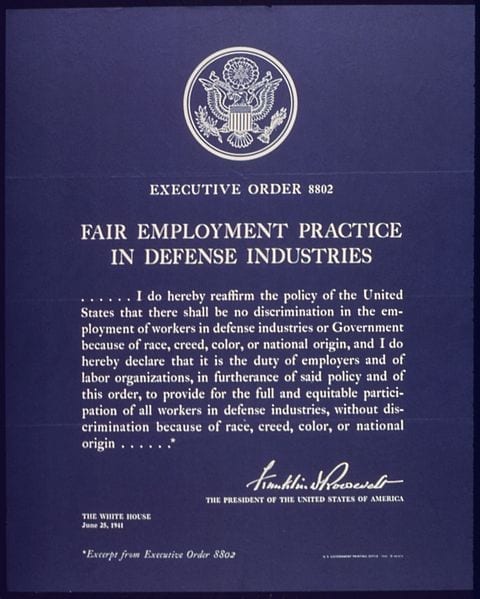

The recent bill, H.R. 1776, called the “Lease-Lend Bill,” seeks to confer upon the President authority unheard of in our history. It seeks to vest in the executive powers which the President says he does not want and would not accept but for the emergency. The opponents of the bill claim that it amounts to an abdication by Congress of its responsibility and that it is not necessary at this time.

Fortunately, out of the hearings the American people will learn what are the factors which it is claimed make the bill necessary, what is the meaning of its proposals in detail, and what powers are to be exercised. Personally, I am a great believer in centralized responsibility, and therefore believe in conferring all powers necessary to carry out that responsibility.

Moreover, I appreciate full well that time is of the essence. Nevertheless, I am unable to agree with the proponents of this bill that it has yet been shown that we face such immediate danger as to justify this surrender of the authority and responsibility of the Congress. I believe that after the hearings have been completed there will be revealed less drastic ways of meeting the problem of adequate authority for the President.

However, after there has been debate and a bill, whatever it may be, becomes part of our law, I think the duty of every American citizen is plain. All of us must rally behind the President so that he may carry on with a nation which has debated in the democratic manner, has acted in the democratic manner and is united in the cause of preserving our own democracy.

Regardless of what our foreign policy should be, it is obvious that as a nation we must go “all out” for rearmament. It is only in this way that the American people can realize their national policy of security and their desire to help England. The more we rearm, the larger our arsenal, the more we shall have available for England. There is no need to fear if we prepare. Our Bill of Rights will he intact if we hold a free and open discussion and maintain tolerance for those with whom we disagree. No one group or one class can possibly bear the burden of sacrifice which must be borne by every man, woman and child, rich and poor alike, even if our present program is the limit. But no burden is too great a price to pay for the safety of our beloved country.

Eventually we may have to fight to defend our civilization. The future in that respect is unknown and unknowable. Let us all appreciate here and now that come what may in the fortunes of war, our easy life of yesterday is at an end. Our lot in the future will be a difficult one—win, lose or draw.

America has had enough of words. Our friends across the water want more than phrases. Words will not give them armaments ; words will not make us strong. America must unite—now. America must sacrifice—now. America must work—now.

I do not pretend that by staying at peace our path will be easy. But I do assert that by staying at peace we will be in a far better position to meet the gigantic problems we must face.

The American people want to avoid war. If the leaders keep constantly before them what war means in terms of human tragedy, if Congress is ever alert to the dangers of involvement, the national determination will be translated into effective action and this country will not go to war.

Inaugural Address (1941)

January 20, 1941

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.