Introduction

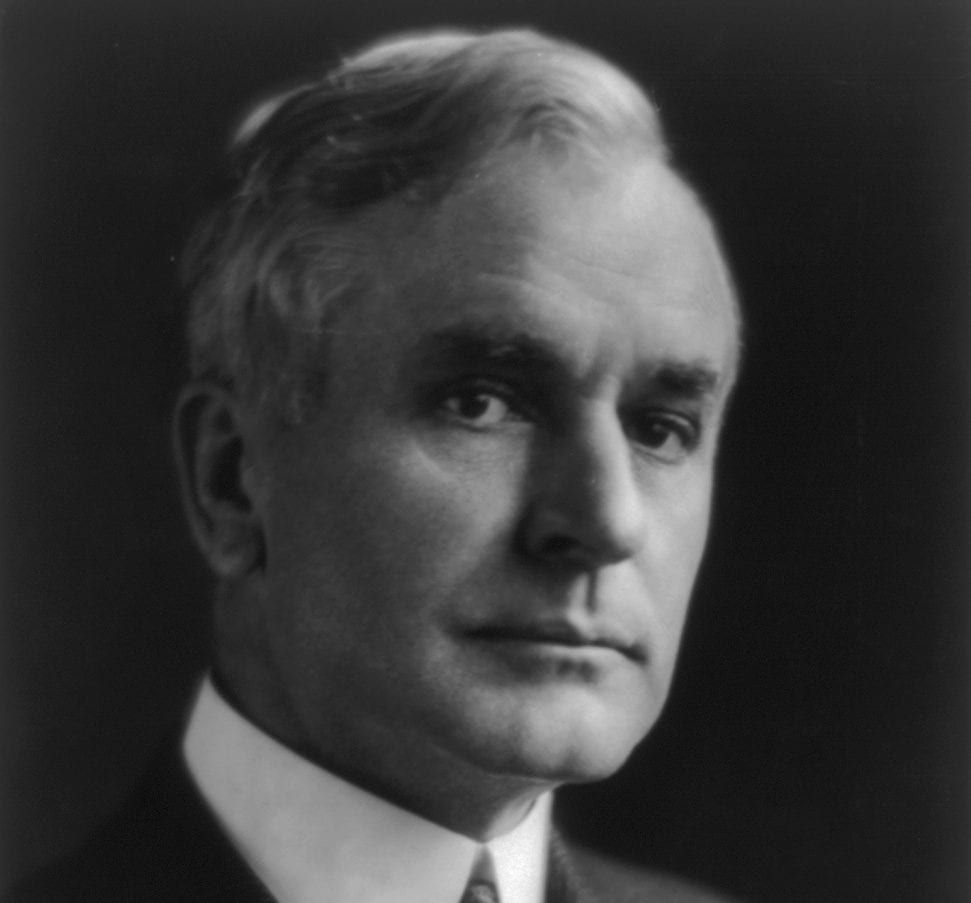

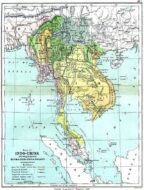

At 6 am on December 7, 1941, the Japanese launched two consecutive attacks on the American fleet stationed at Pearl Harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii. The Japanese sank or damaged 18 ships (including 8 battleships) and killed 2,405 Americans. Over the next 24 hours, the Japanese attacked British, Dutch, and American territories (including Guam and the Philippines) in Southeast Asia. In this diary excerpt, Secretary of Agriculture Claude R. Wickard recounted the president’s conversation with his Cabinet officers and Congressional leaders after the attack on Pearl Harbor. It reveals the sense of confusion and misinformation in the hours after the attack.

Source: Claude R. Wickard Papers, Department of Agriculture Files: Cabinet Meetings, 1941-1942 (Box 13). https://goo.gl/EirzuB.

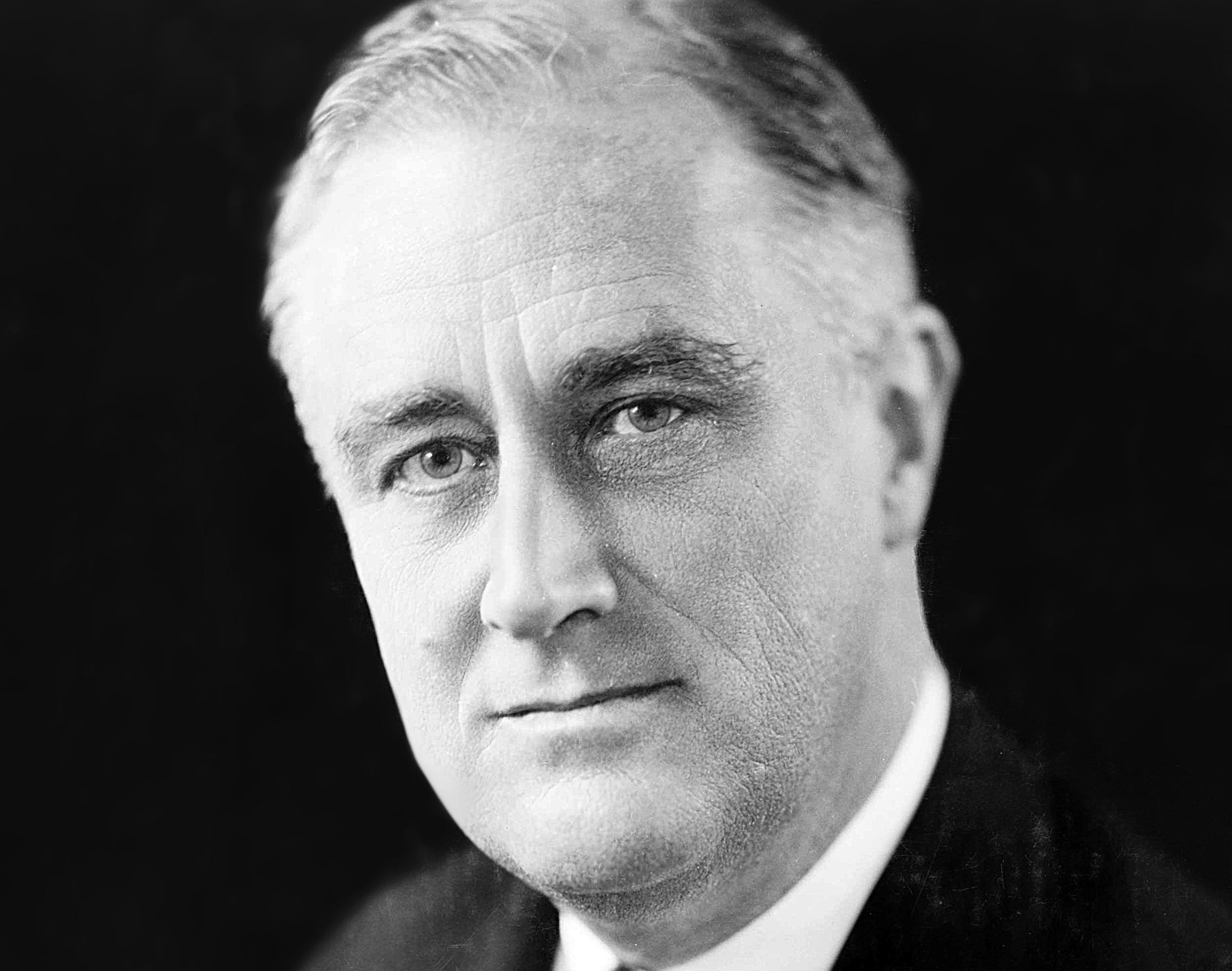

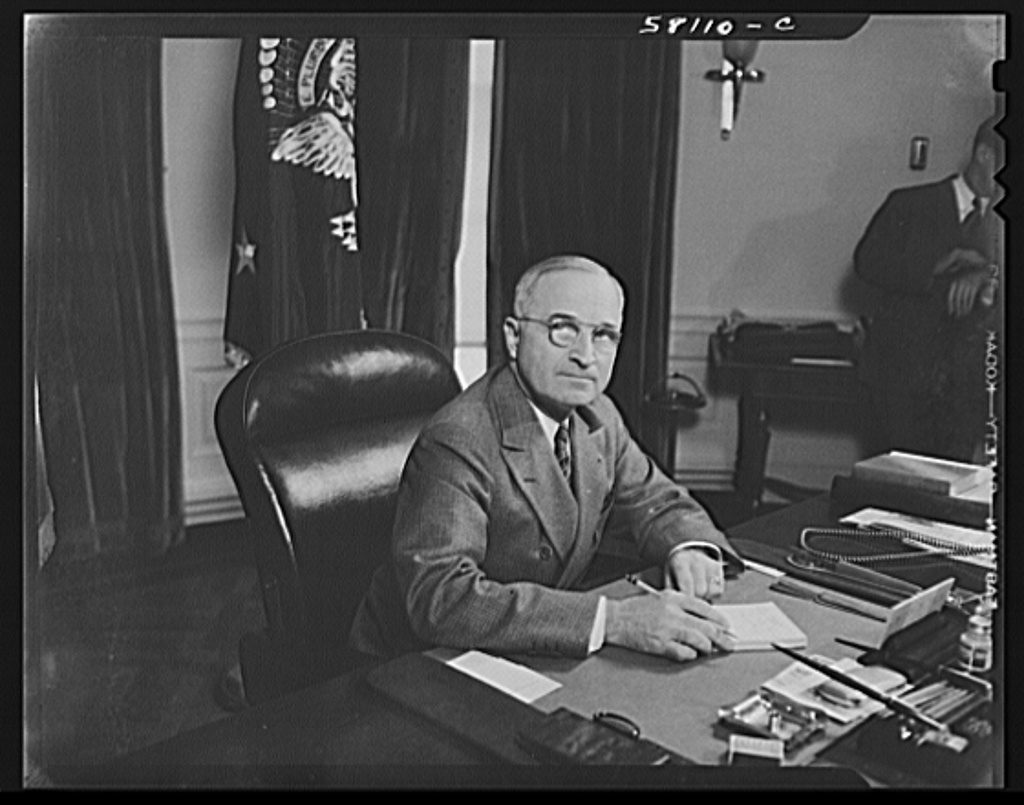

At about four o’clock on the afternoon of December 7, I received a call from the White House saying that there would be a special meeting of the Cabinet in the President’s study in the White House proper at 8:30 that evening. I had been writing all afternoon and Louise1 had been busy so we had not listened to the radio, but I immediately concluded that the Japanese situation had taken a turn for the worse. Within a few minutes after the White House call we were able to get from radio reports that Honolulu and perhaps Manila had been attacked.2 Later the announcers said that Manila had not been attacked but that three or four hundred lives had been lost in attacks in Hawaii.

The Cabinet members were ushered into the President’s study at 8:40. Harry Hopkins was present.3 The President began by saying that this was the most important Cabinet meeting since 1861. He then told of the attack today in Hawaii. He said the attack was a serious one which he would describe later. He continued by saying that there was no question but that the Japanese had been told by the Germans a few weeks ago that they were winning the war and that they would soon dominate Africa as well as Europe. They were going to isolate England and were also going to completely dominate the situation in the Far East. The Japs had been told if they wanted to be cut in on the spoils they would have to come in the war now.

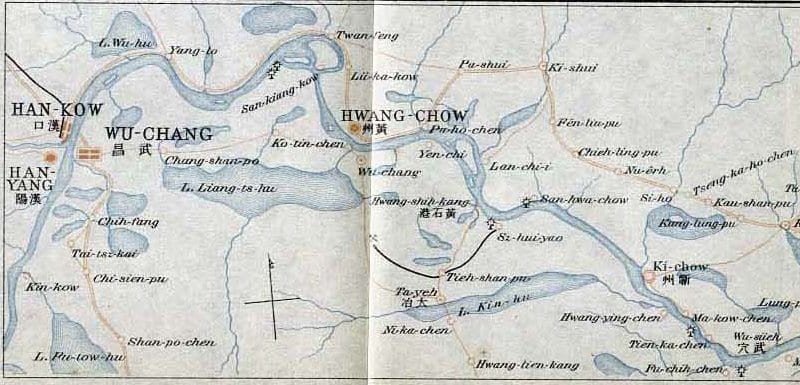

The President said that it would have been necessary to start making plans for today’s attack at least three weeks ago. He then related how the Japanese Envoys, even today, had asked for a conference with Secretary Hull at the hour when the attack was being made in Hawaii.4 He said that the Japanese had started a war [while] carrying on peace negotiations.

The President said that Guam and Wake Islands were also under attack.5 He said these Islands were poorly fortified and that they would soon be in Japanese hands. He then read a message which he said he was going to read tomorrow at a joint session of Congress. He said that the message was subject to revision as later events might warrant. The message was short and merely stated how Japan had attacked while still carrying on peace negotiations. It ended by stating that he was asking Congress to declare that a state of war had existed since Japan’s attack. He indicated that he did not know whether Japan had declared war or not. He also said there was a chance that the Germans would also declare war. There was considerable discussion of the proposed message. Secretary Hull said that he thought that there should be a complete statement on the events leading up to the attack. The President disagreed but Hull said he thought the most important war in 500 years deserved more than a short statement. Secretary Stimson said that Germany had inspired and planned this whole affair and that the President should so state in his message.6 The President disagreed with this suggestion.

The President went into the confidential reports of the attack which he said must be kept in strict secrecy. He first indicated that aircraft had been destroyed in large numbers in the attack. He then revealed that six out of seven of the battleships in Pearl Harbor had been damaged – very severely. I was shocked at the news; so were other members of the cabinet. The Secretary of the Navy lost his air of bravado.7 Secretary Stimson was very sober.

The President said that the Japanese were hoping to bring about the transfer of American naval vessels from the Atlantic to the Pacific. He said he wanted to avoid this if [at] all possible. He said that he didn’t want to tell Congressional leaders (of both parties – including Senators Barkley, Johnson, Austin and Connally, Speaker Rayburn, and Congressmen Jere Cooper, Martin, Bloom, and Doxey) who were waiting to come to his study all the things he had told us.8

When they came in he said that it was very unpleasant to be a War President and then he recounted the series of events leading up to the attacks of today. He said that he wanted to deliver a message to a joint session of Congress tomorrow. After a short discussion it was decided to have him address the session at 12:30. Some of the Congressmen wanted to know if he were going to ask for a declaration of war. The President said he didn’t know yet what he was going to say because the events of the next fourteen hours would be numerous and all-important. The President revealed that at least battleships were damaged. This caused considerable consternation among the Congressional leaders. Connally asked what damage we had inflicted on the Japs. The President indicated he didn’t know but went on to say we had no information to indicate that we had severely damaged the Japs. Connolly exploded by saying: “Where were our forces – asleep? How can we go to war without anything to fight with?” The President told how the Germans might have been five hundred miles away at dark last night since they had twelve hours of sailing in the long darkness.

The President went on to say that the distance to Japan made it very difficult for us to attack Japan. He said that each thousand miles from base cut the efficiency of the Navy five percent. He pointed out that it would be necessary to strangle Japan rather than whip her and that it took longer. He once spoke about two or three years being required.

The meeting broke up about 10 o’clock. Everyone was very sober. The President began to dictate a statement for the press. Some of us stayed around for nearly an hour. I talked to the Vice President9 who said many times that it was all for the best. I reminded him that he had made a similar statement when we were at the Convention at Chicago last year when it seemed that everything was crashing around us.10

Through it all the President was calm and deliberate. I could not help but admire his clear statements of the situation. He evidently realizes the seriousness of the situation and perhaps gets much comfort out of the fact that today’s action will unite the American people. I don’t know anybody in the United States who can come close to measuring up to his foresight and acumen in this critical hour.

As I drove home I could not refrain from wondering at the fates that caused me to be present at one of the most important conferences in the history of this nation.

- 1. Wickard’s wife

- 2. Japan invaded the Philippines on December 8, 1941.

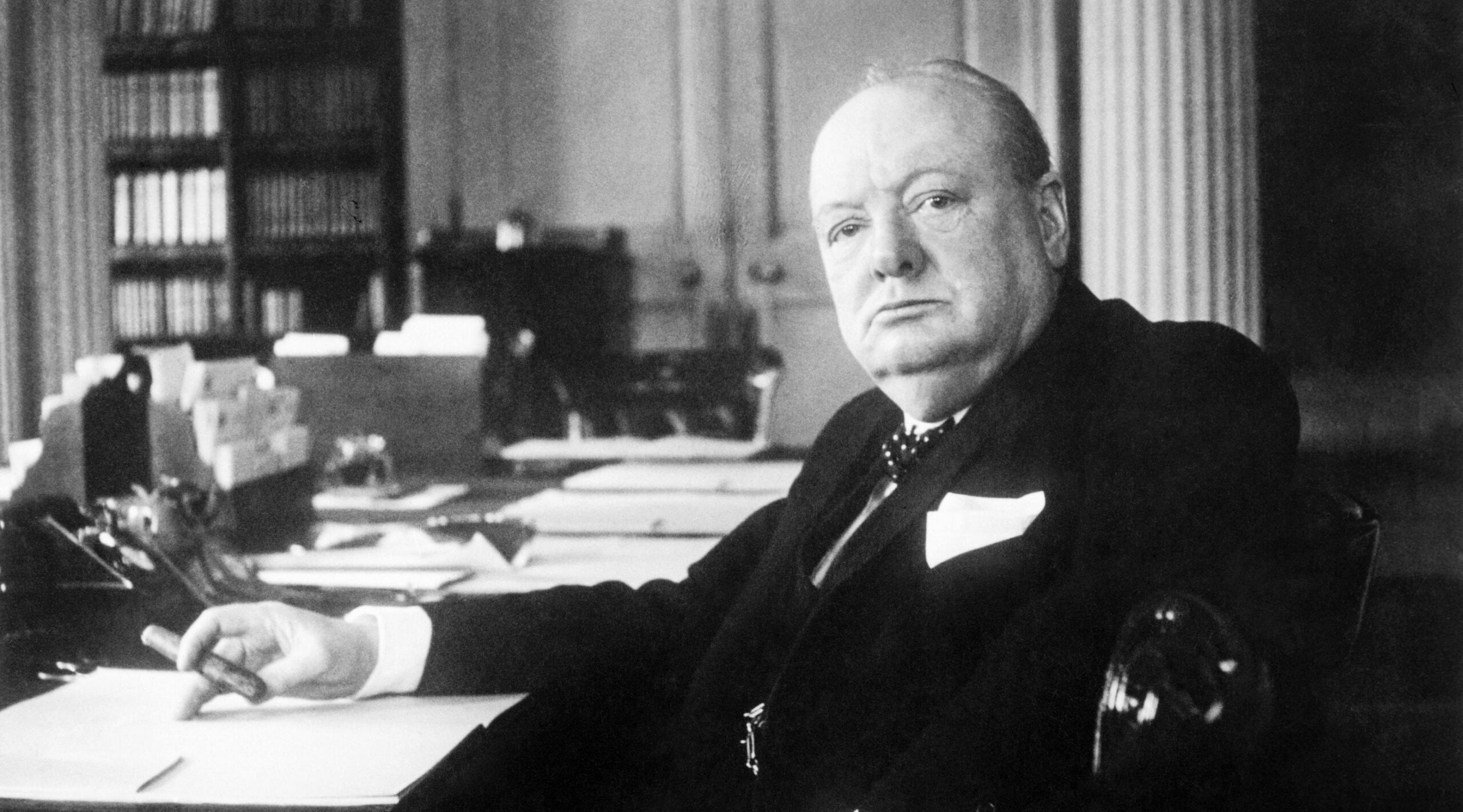

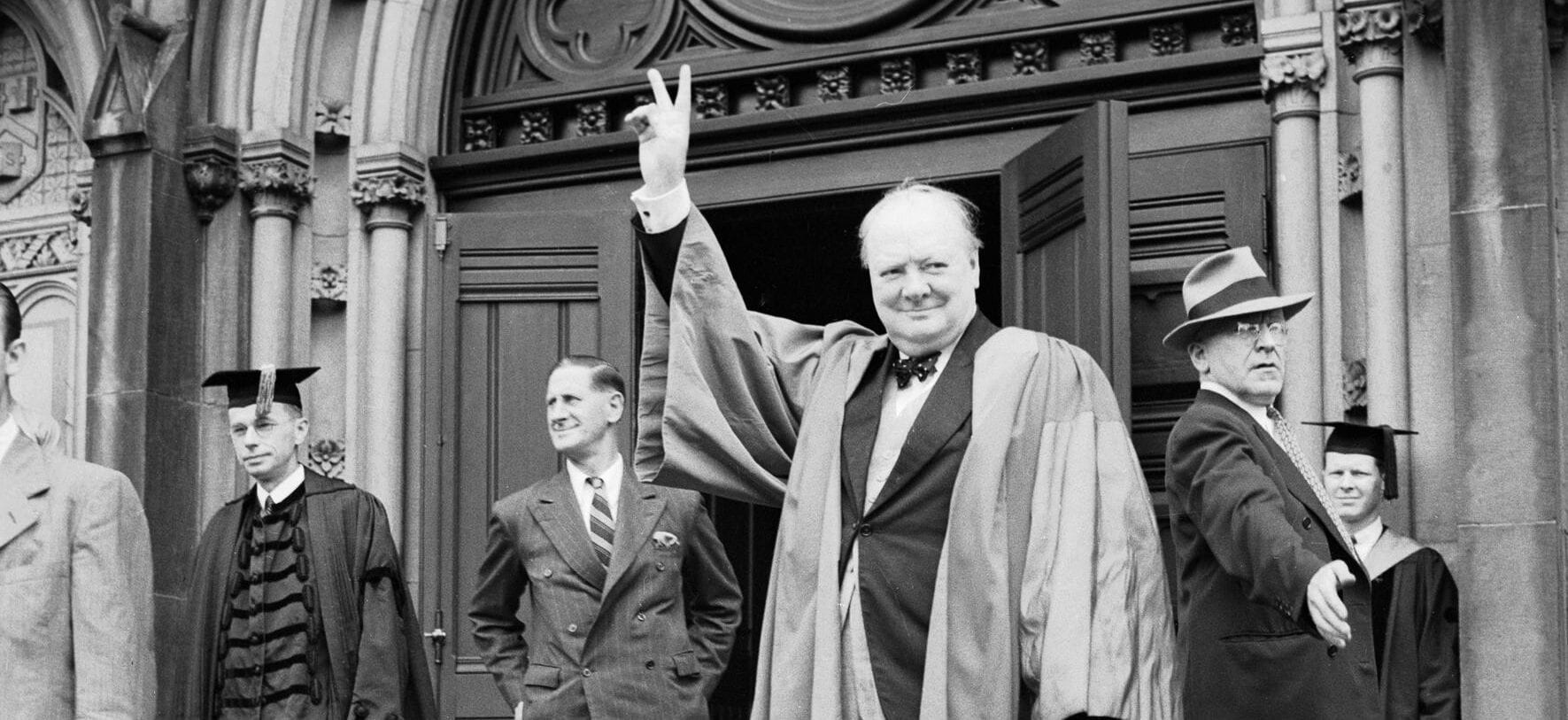

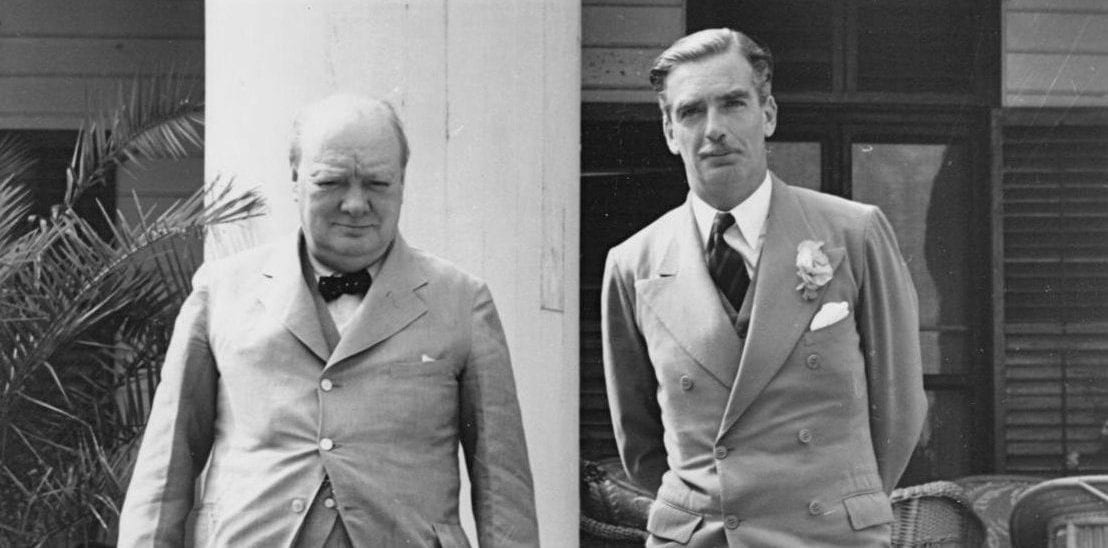

- 3. Harry Hopkins was a close advisor to FDR, chief architect of the New Deal, and an informal emissary to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill during World War II.

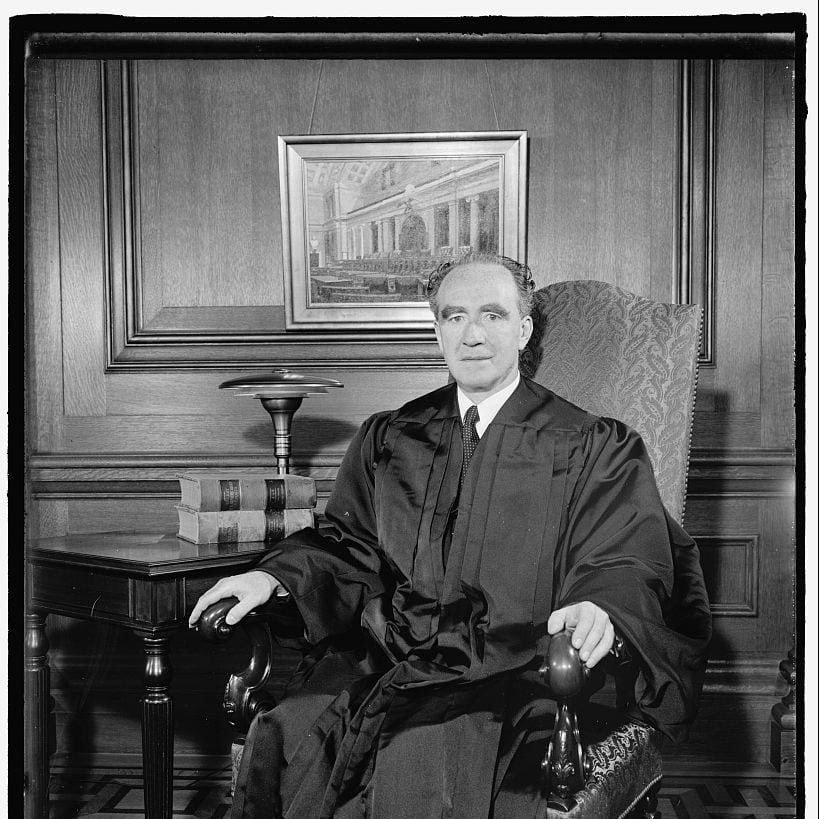

- 4. Cordell Hull was Secretary of State from 1933-1944.

- 5. Located 2,496 miles due east of the Philippines, Guam is an island in the southwest Pacific. During the Spanish American War, the United States captured Guam, which from 1565 to the early nineteenth century had been an important base for Spanish ships traveling from Spanish Mexico to the Spanish Philippines. (Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821.) Following the war it became an American territory, which it remains. The Japanese captured Guam on December 7, 1941. The United States retook the island July 21, 1944. Wake Island is 1,500 miles east of Guam. The United States had taken possession of Wake in 1898, the same year it annexed the Hawaiian Islands and took Guam and the Philippines in the Spanish-American War. Naval facilities on the islands were part of the infrastructure through which the United States controlled the Pacific Ocean. The Japanese captured Wake on December 23, 1941 and held it until the end of the war.

- 6. Henry L. Stimson was Secretary of War from 1940-1945.

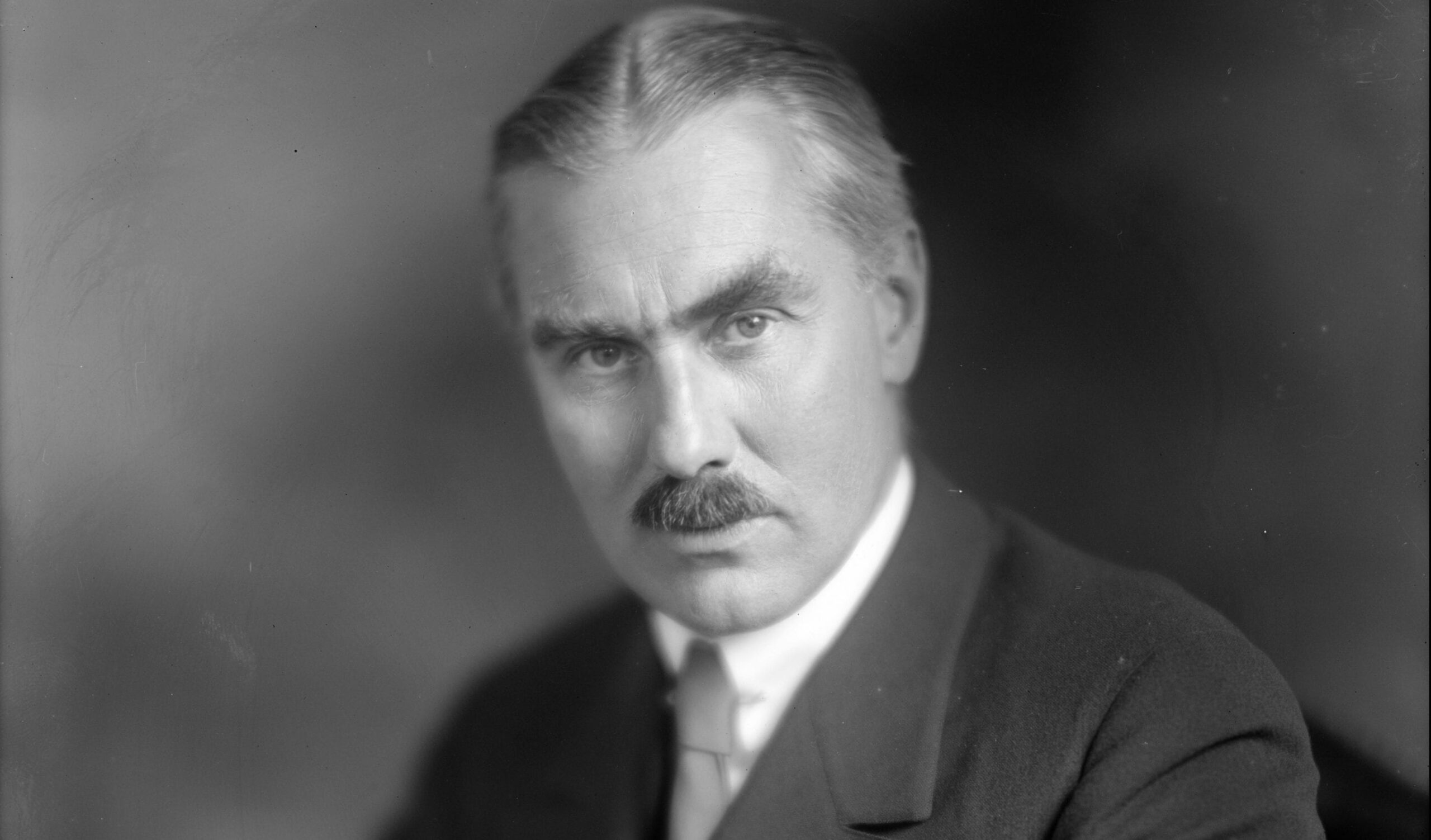

- 7. William Franklin “Frank” Knox was Secretary of the Navy from July 1940 until his death on April 28, 1944. A newspaper publisher, he was also the Republican nominee for Vice President in 1936. Because Knox supported aid to Britain, and Roosevelt wanted to create bi-partisan support for his defense policies, Roosevelt appointed Knox to his cabinet after the fall of France to the Nazi invasion. Although a forceful advocate for the war effort, Knox was not an active administrator. During his tenure, naval operations were handled for the most part by Chief of Naval Operations Ernest J. King and Assistant Secretary James Forrestal.

- 8. Alben Barkley (D-Kentucky), who was Senate majority leader; Hiram Johnson (R-California); Warren Austin, (R-Vermont), who was assistant minority leader; Tom Connally, (D-Texas), who was chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee; Sam Rayburn (D-Texas); Jere Cooper, (D-Tennessee); Joseph Martin, (R-Massachusetts), who was House minority leader; Sol Bloom, (D-New York), who was chairman of the House committee on foreign affairs; Wall Doxey (D-Mississippi).

- 9. Henry Wallace

- 10. Wickard may be referring here either to the controversy surrounding Roosevelt’s nomination for an unprecedented third term or to the opposition that Wallace, who was viewed as having socialist sympathies, received as the Vice-Presidential nominee.

A Date Which Will Live in Infamy

December 08, 1941

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.