Introduction

William A. Peffer (1831–1912) was a newspaper editor, author, lawyer, and U.S. senator from Kansas (1891–97). He was especially influential as founding editor of The Kansas Farmer, a populist newspaper that, among other things, argued for railroad regulation, the dismantling of monopolies, various financial reforms, and initiative and referendum. The Kansas Farmer became the official state paper of the Farmers’ Alliance, a populist agrarian movement and precursor to the Populist Party (See The Populist Party Platform and Expression of Sentiments).

Peffer held the distinction of being the first of six Populist Party members elected to the U.S. Senate. He was the first non-Republican U.S. senator from Kansas and the only Populist senator to be succeeded by another Populist (William A. Harris). In the piece below, Peffer explained the mission of the Populist Party, focusing especially on the party’s call for railroad, land, and financial reform.

Source: William A. Peffer, “The Mission of the Populist Party,” North American Review 157, no. 445 (December 1893): 665–78, available online at the Hathi Trust Digital Library: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112046447717;view=1up;seq=671.

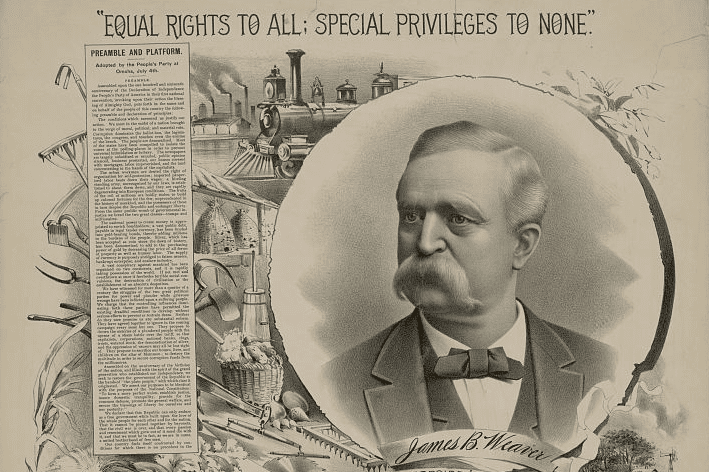

The Populist Party is an organized demand that the functions of government shall be exercised only for the mutual benefit of all the people. It asserts that government is useful only to the extent that it serves to advance the common weal. Believing that the public good is paramount to private interests, it protests against the delegation of sovereign powers to private agencies. Its motto is: “Equal rights to all; special privileges to none.” Its creed is written in a single line of the Declaration of Independence—“All men are created equal.” Devoted to the objects for which the Constitution of the United States was adopted, it proposes to “form a more perfect union” by cultivating a national sentiment among the people; to “insure domestic tranquility” by securing to every man and woman what they earn; to “establish justice” by procuring an equitable distribution of the products and profits of labor; to “provide for the common defence” by interesting every citizen in the ownership of his home; to “promote the general welfare” by abolishing class legislation and limiting the government to its proper functions; and to “secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity” by protecting the producing masses against the spoliation of speculators and usurers.

The Populist claims that the mission of his party is to emancipate labor. He believes that men are not only created equal, but that they are equally entitled to the use of natural resources in procuring means of subsistence and comfort. He believes that an equitable distribution of the products and profits of labor is essential to the highest form of civilization; that taxation should only be for public purposes, and that all moneys raised by taxes should go into the public treasury; that public needs should be supplied by public agencies, and that the people should be served equally and alike.

The party believes in popular government. Its demands may be summarized fairly to be—

- An exclusively national currency in amount amply sufficient for all the uses for which money is needed by the people, to consist of gold and silver coined on equal terms, and government paper, each and all legal tender in payment of debts of whatever nature or amount, receivable for taxes and all public dues.[1]

- That rates of interest for the use of money be reduced to the level of average net profits in productive industries.

- That the means of public transportation be brought under public control, to the end that carriage shall not cost more than it is reasonably worth, and that charges may be made uniform.

- That large private land-holdings be discouraged by law. . . .

The Populist Party is the only party that honestly favors good money. . . . We have seven different kinds of money, and only one of them is good, according to the determination of the Treasury officials. Bank notes are not legal tender, neither are silver certificates, nor gold certificates. Treasury notes are not legal tender in cases where another kind of money is expressed in the contract, and United States notes (greenbacks) will not pay either principal or interest on any government bond. None of our paper money is taxable. Silver dollars are by law full legal tender in payment of debts to any amount whatever, but the Treasury does not pay them out on any obligation unless they are specially requested. In practice, we have but one full legal tender money—gold coin; and Republicans and Democrats are agreed on continuing that policy; while Populists demand gold, silver, and paper money, all equally full legal tender.

The fact that we have now out about $700,000,000 in paper is proof that our stock of coin is utterly inadequate to perform all the money duty required in the people’s business transactions. The discontinuance of silver coinage stops the supply from that source. It is believed by men best informed on the subject that the gold used in the arts has reached an amount about equal to the annual output of the mines. Then the world’s stock of gold coin will not be increased unless the arts are drawn upon, and that can be done successfully only at a price above the money value of the coin. Russia, Austria, Italy, and the United States all want more gold. Where is it to come from? And what will it cost the purchaser? Are we to drop back to Roman methods of procuring treasure? When all the nations set out on gold-hunting expeditions, who will be the victor and what will become of the spoils?

It is evident that we must have more money, and Congress alone is authorized to prepare it. States are prohibited by the Constitution of the United States from making anything but gold and silver coin a legal tender in payment of debts, and nothing is money that is not a tender.[2] The people can rely only on Congress for a safe circulating medium.

Populists demand not only a sufficiency of money, but a reduction of interest rates at least as low as the general level of the people’s savings. They aver that with interest at present legal and actual rates, an increase in the volume of money in the country would be of little permanent benefit, for bankers and brokers would control its circulation, just as they do now. But with interest charges reduced to 3 or 2 percent, the business of the money-lender would be no more profitable than that of the farmer—and why should it be? . . .

. . . The rate of interest ought to be what, with prudent management through a reasonable number of average seasons, he [the farmer] can pay yearly, with part of the principal, until he has paid out and has the farm left.

Three percent, compounded annually is a fair average the world over for labor’s saving. It has been a little more in the United States, but a gold basis will soon bring us to the general level, and that will settle lower as population and trade increase.

While the Populist Party favors government ownership and control of railroads, it wisely leaves for future consideration the means by which such ownership and control can best be brought about. The conditions which seem to make necessary such a change in our transportation system preclude all probability of its ever being practicable, if it were desirable, to purchase existing railway lines. The total capitalization of railroads in the United States in 1890 was put at $9,871,378,389—nearly ten thousand million dollars. It would be putting the figures high to say that the roads are worth one-half the amount of their capital stock. This leaves a fictitious value of $5,000,000,000 which the people must maintain for the roads by transportation charges twice as high as they would be if the capitalization were only half as much. It is the excessive capitalization which the people have to maintain that they complain about. It would be an unbusinesslike proceeding for the people to purchase roads when they could build better ones just where and when they are needed for less than half the money that would be required to clear these companies’ books. It is conceded that none of the highly capitalized railroad corporations expect to pay their debts. If they can keep even on interest account, they do well, and that is all they are trying to do. While charges have been greatly reduced, they are still based on capitalization, and courts have held that the companies are entitled to reasonable profits on their investment. The people have but one safe remedy—to construct their own roads as needed, and then they will “own and control” them.

This is not a new doctrine. A select committee of the Senate of the United States, at the head of which was Hon. William Windom, then a senator and afterward secretary of the Treasury appointed in December 1872, reported among other recommendations one proposing the construction of a “government freight railway,” for the purpose of effectively regulating interstate commerce.[3] A government freight railway would have no capitalization, no debt, bonded or otherwise; its charges would be only what it would cost to handle the traffic and keep the road in repair. That would reduce cost of carriage to a minimum, and nothing else will.

Populists complain of legislation in the interest of favored classes. At the very time when the homestead law was passed a scheme was hatching to absorb the public lands by railway corporations.[4] Scarcely had the great war begun when a plan was laid to establish a system of national banking based on the people’s debts;[5] and while customs duties were raised to increase the public revenues, cheap foreign labor was brought in under contract to man the factories. Banks have been specially favored.

When it was to their interest to withdraw their notes it was done with impunity. They have been permitted to openly violate the law that authorizes their existence, and this without rebuke.

The U.S. Senate shields them from exposure. When the Treasury was flush, public moneys were lavishly left with the banks to use without interest, and when the great banks in New York City needed funds to relieve the stringency in the “money market” there, they had only to ask and they received. And now that the Treasury is running short in gold reserves, there is a demand for more bonds to purchase more gold to be used in redeeming Treasury notes which the law requires to be redeemed in silver, thus again reducing the reserves, making another bond issue necessary to procure more gold; and so on, as the “money market” may require. These “Napoleons of Finance” are playing a bold game. . . .

Rapid accumulation of wealth by a few citizens, as we have seen it in the United States during the last thirty years, is evidence of morbidly abnormal conditions. It is inconsistent with free institutions. It is breeding anarchy and trouble. No man can honestly take to himself what he does not earn; and if he does no more than that, riches will come to him slowly. It is only when he gets what he does not earn that his “success” attracts attention. Fortunes running into millions of dollars must be made up of property and profits mostly produced and earned by persons other than those who claim them.

No man ever earned a million dollars. If he was moved to great undertakings, nature’s God inspired him. And if, in the play of his ambition he marshaled effective forces, his equipment cost him little. To a great mind success is compensation. The value of its labor cannot be measured with money. A strong man’s intellect moves as easily as a blacksmith’s arm. Both are gifts.

The best men are content with little. Vast enterprises that move the world are maintained by contributions from the labor of the poor. Leaders do but organize and direct; the rank and file do all the rest. Apply the “iron law of wages” equally to all that work and you scale down the salaries of many useless people. If the Republic is to endure we must encourage the average man.

- 1. See The “Cross of Gold” Address for an explanation of the importance of silver coinage to the populist movement.

- 2. Article 1, section 10.

- 3. A Republican, William Windom (1827–1891) represented Minnesota as a U.S. congressman and a U.S. senator. He served as secretary of the Treasury under President Benjamin Harrison.

- 4. In order to support westward expansion, Congress passed the Homestead Act in 1862. Under the legislation, an individual could claim up to 160 acres of government land, provided the individual paid a filing fee, worked that land, and applied for a deed.

- 5. The “great war” was the Civil War.

King Debs, in Harper’s Weekly

July 14, 1894

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.