No related resources

Introduction

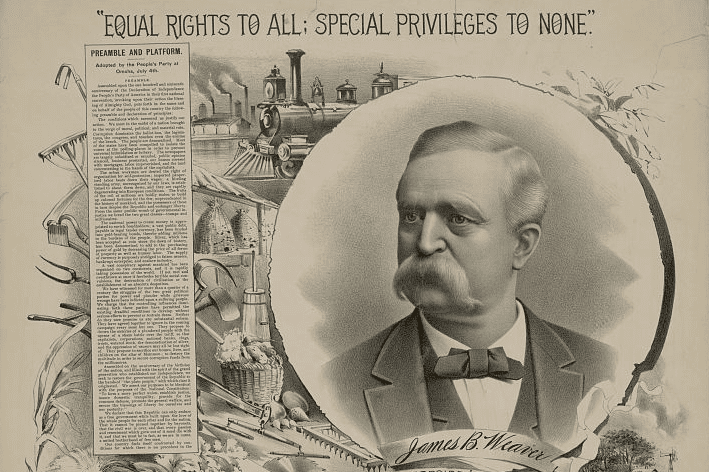

The farmers’ movement that developed after the Civil War in the western United States became a broader populist movement that pitted farmers and workers against those who appeared to benefit most from the emerging industrial economy. The populist movement criticized economic stratification and the special privileges that corporations enjoyed by using their economic power to influence political decisions in their favor. When the farmer and populist movements spread into the southern United States, some of their leaders at first sought to rally poor farmers, both black and white, to fight against the influence of the established landowners and political leaders of the Democratic Party. According to the populists, these leaders were carrying on the aristocratic ways of the antebellum planter class. In response, the established leaders appealed to racial antagonism to break up such attempts at reform, describing those who sought reforms as a threat to continued white supremacy. To understand the context of such political disputes, it is important to remember that South Carolina’s population, for example, was majority black until about 1920.

The Shell Manifesto, associated with the populist reform effort, was intended to rally support for Benjamin R. “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman (1847–1918), a wealthy South Carolina farmer, in the 1890 governor’s election. Tillman had helped organize farmers in the state and had twice run unsuccessfully for governor. The Manifesto argued for the populist program of lower taxes and more access to the opportunities enjoyed by the wealthy (especially in education), but also stressed white supremacy to counter the claim of the established Democratic Party that reform threatened white control. The Manifesto, characterized a few months later in the paper that first published it as “notorious” and “communistic,” inaugurated “a bitter fight” in the Democratic Party. Tillman won the fight by winning election in 1890. Interestingly, the Manifesto criticized lynchings, which were peaking around this time, and as governor, Tillman initially took some measures to curb these extrajudicial killings. Nevertheless, Tillman was a racist who supported “redemption.” He also supported the disenfranchisement of blacks through poll taxes and other measures and the establishment of legal segregation. He later became a U.S. senator from South Carolina and defended both segregation and lynching in the Senate. (For an example, see his speech on black disenfranchisement in the Core Documents volume Slavery and Its Consequences.)

Source: News and Courier, Charleston, SC, January 23, 1890, p. 1. It also appeared in the News and Courier on July 10, 1890, p. 5, with the commentary referred to in the introduction.

THE COMING CAMPAIGN, A CONTEST PROPOSED WITHIN THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY

An Address to the Democrats of South Carolina, Issued by Order of the Executive Committee of the Farmers’ Association of South Carolina.

Mr. W. G. Shell of Laurens, president of the Farmers’ Association of South Carolina, requests the News and Courier1 to publish the following address:

To the Democracy of South Carolina:2 For four years the Democratic Party in the state has been deeply agitated, and efforts have been made at the primaries and conventions to secure retrenchments and reform, and a recognition of the needs and rights of the masses. The first Farmers’ convention met in April 1886. Another in November of the same year perfected a permanent organization under the name of the “Farmers Association of South Carolina.”3 This association, representing the reform element in the party, has held two annual sessions since, and at each of these four conventions, largely attended by representative farmers from nearly all of the counties, the demands of the people for greater economy in the government, greater efficiency in its officials, and a fuller recognition of the necessity for cheaper and more practical education have been pressed upon the attention of our legislature.

In each of the two last Democratic state conventions the “Farmers’ Movement” has had a large following and we only failed of controlling the convention of 1888 by a small vote—less than twenty-five—and that, too, in the face of the active opposition of nearly every trained politician in the state. We claim that we have always had a majority of the people on our side, and have only failed by reason of the superior political tactics of our opponents and our lack of organization. . . .

The executive committee of the Farmers’ Association did not deem it worthwhile to hold any convention last November, but we have watched closely every move of the enemies of economy—the enemies of true Jeffersonian democracy—and we think the time has come to show the people what it is they need and how to accomplish their desires. We will draw up the indictment against these who have been and are still governing our state, because it is at once the cause and justification of the course we intend to pursue.

South Carolina has never had a real republican government. Since the days of the “Lords Proprietors”4 it has been an aristocracy under the forms of democracy, and whenever a champion of the people has attempted to show them their rights and advocated those rights an aristocratic oligarchy has bought him with an office, or failing in that turned loose the floodgates of misrepresentation and slander in order to destroy his influence.

The peculiar situation now existing in the state, requiring the united efforts of every true white man to preserve white supremacy and our very civilization even has intensified and tended to make permanent the conditions which existed before the war. Fear of a division among us and consequent return of a negro rule has kept the people quiet, and they have submitted to many grievances imposed by the ruling faction because they dreaded to risk such a division.

The “Farmers’ Movement” has been hampered and retarded in its work by this condition of the public mind, but we have shown our fealty to race by submitting to the edicts of the party and we intend, as heretofore, to make our fight inside the party lines, feeling assured that truth and justice must finally prevail. The results of the agitation thus far are altogether encouraging. Inch by inch and step by step true democracy—the rule of the people—has won its way. We have carried all the outposts. Only two strongholds remain to be taken, and with the issues fairly made up and plainly put to the people we have no fear of the result. The House of Representatives has been carried twice, and at last held after a desperate struggle.

The advocates of reform and economy are no longer sneered at as “three for a quarter statesmen.” They pass measures of economy which four years ago would have excited only derision, and with the Farmers’ Movement to strengthen their backbone have withstood the cajolery, threats, and impotent rage of the old “ring bosses.”5 The Senate is now the main reliance of the enemies of retrenchment and reform, who oppose giving the people their rights. The Senate is the stronghold of “existing institutions” and the main dependence of those who are antagonistic to all progress. As we captured the House we can capture the Senate; but we must control the Democratic state convention before we can hope to make economy popular in Columbia. . . .

The General Assembly is largely influenced by the idea and policy of the state officers, and we must elect those before we can say the Farmers’ Movement has accomplished its mission. It is true that we have wrenched from the aristocratic coterie who were educated at and sought to monopolize everything for the South Carolina College,6 the right to control the land script and Hatch fund7 and a part of the privilege tax on fertilizers for one year, and we have $40,000 with which to commence building a separate agricultural college, where the sons of poor farmers can get a practical education at small expense.

But we dare not relax our efforts or rely upon the loud professions of our opponents as to their willingness now to build and equip this agricultural school. . . .

All the cry about “existing institutions” which must remain inviolate shows that the ring—the South Carolina University, Citadel, Agricultural Bureau, Columbia Club, Greenville building ring—intend in the future, as in the past, to get all they can, and keep all they get. These pets of the aristocracy and its nurseries are only hoping that the people will again sink into their accustomed apathy. . . .

We have never and do not now want any increase of taxes to accomplish these ends. . . .

Of all the taxes we pay, the pensions to Confederate veterans are submitted to most willingly, and we regret that we cannot increase the pittance they receive. But the continuance of men in office as political pensioners, after their ability or willingness to serve the people is gone—when the interests and even rights of the people are thereby sacrificed, this pandering to sentiment, this favoritism—is a crime, nothing more and nothing less. Rotation in office is a cardinal democratic principle, and the neglect to practice it is the cause of many of the ills we suffer.

We cannot elaborate the other counts in this indictment. We can only point briefly to the mismanagement of the Penitentiary, which is a burden on the taxpayers, even while engaged in no public works which might benefit the state. To the wrong committed against the people of many counties (strongholds of Democracy)8 by the failure to reapportion representation according to the population, whereby Charleston has five votes in the House and ten votes in the state convention, which choose our state officers, to which it is not entitled.

To the zeal and extravagance of this aristocratic oligarchy, whose sins we are pointing out, in promising higher education for every class except farmers, while it neglects the free schools, which are the only chance for an education to thousands of poor children, whose fathers bore the brunt in the struggle for our redemption in 1876.9 To the continued recurrence of horrible lynchings, which we can but attribute to bad laws and their inefficient administration. To the impotence of justice to punish criminals who have money. To the failure to call a constitutional convention that we may have an organic law framed by South Carolinians for South Carolinians and suited to our wants, thereby lessening the burdens of taxation and giving us better government.

Fellow Democrats, do not all these things cry out for a change? Is it not opportune, when there is no national election, for the common people who redeemed the state from Radical rule to take charge of it? Can we afford to leave it longer in the hands of those who, wedded to antebellum ideas, but possessing little of antebellum patriotism and honor, are running it in the interest of a few families and for the benefit of a selfish ring of politicians? As real Democrats and white men, those who here renew our pledge to make the fight inside the Democratic Party and abide the result, we call upon every true Carolinian, of all classes and callings to help us purify and reform the Democratic Party and give us a government of the people, by the people, and for the people.

If we control the state Democratic convention, a legislature in sympathy will naturally follow; failing to do this, we risk losing all we have gained, and have no hope of any change for the better. . . .

We therefore issue this call for a convention of those Democrats who sympathize with our views and purposes, as herein set forth. . . .

By order of the executive committee of the Farmers’ Association of South Carolina.

C. W. Shell

President and ex Officio Chairman

- 1. A newspaper in Charleston, South Carolina.

- 2. That is, to the Democratic Party of South Carolina.

- 3. The Farmers’ Association in South Carolina was part of the broader farmers’ movement that developed in the United States in the 1870s and 1880s.

- 4. South Carolina began as a land grant from the king of England to eight private individuals, known as the Lords Proprietors, with authorization to form a colony.

- 5. A ring is a group of people cooperating for an illegal purpose or one alleged to be contrary to the common good.

- 6. The original name of the University of South Carolina.

- 7. Federal money from the Hatch Act (1877) to set up agricultural experiment stations at state land grant colleges.

- 8. Democratic Party.

- 9. "Redemption” was the euphemism for the return of white control and the beginning of the exclusion of African Americans from political life in the South. Tillman played a prominent role in “redemption.”

Leaders of Men

June 17, 1890

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.