No related resources

Introduction

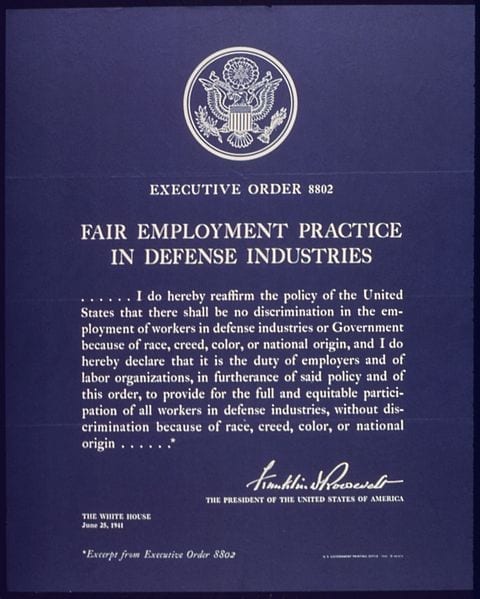

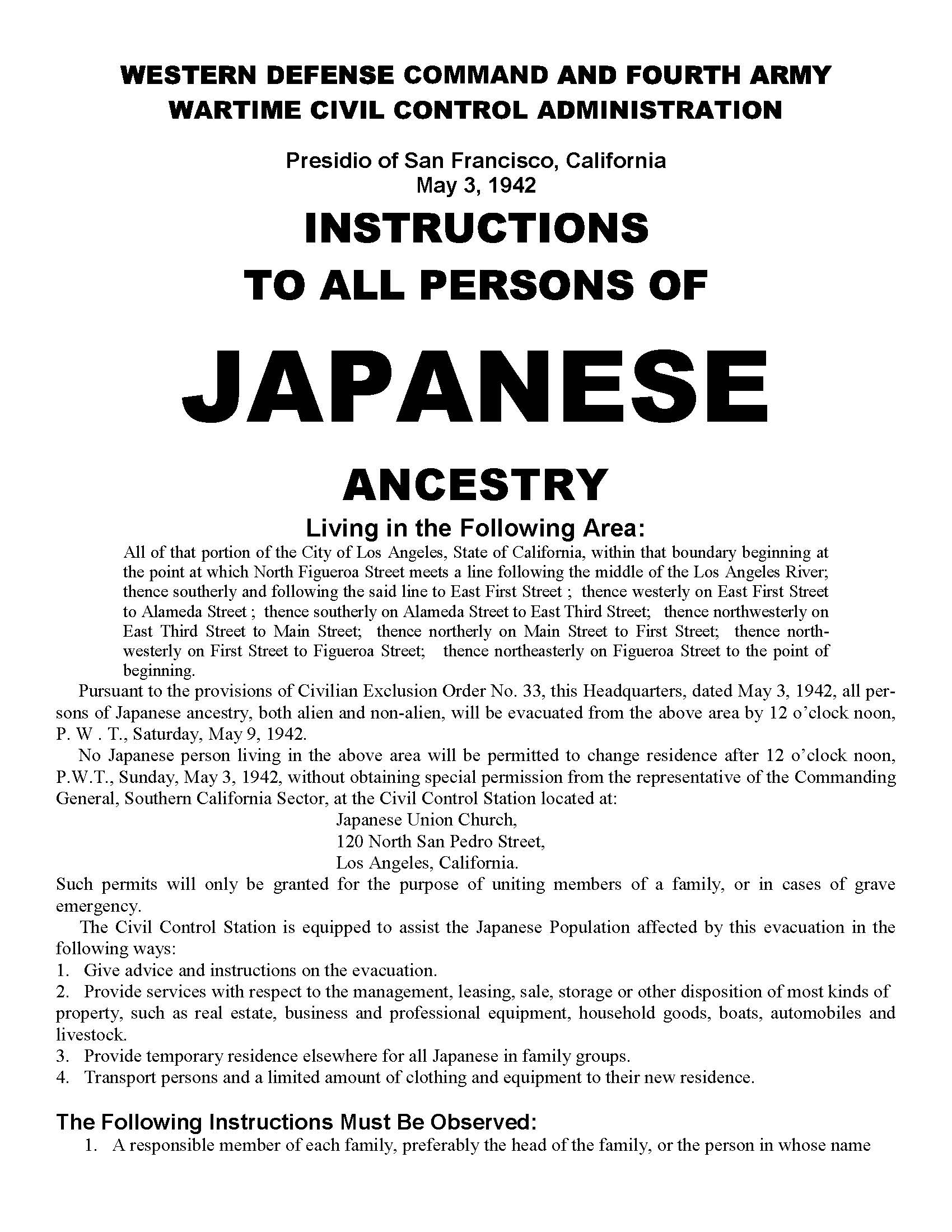

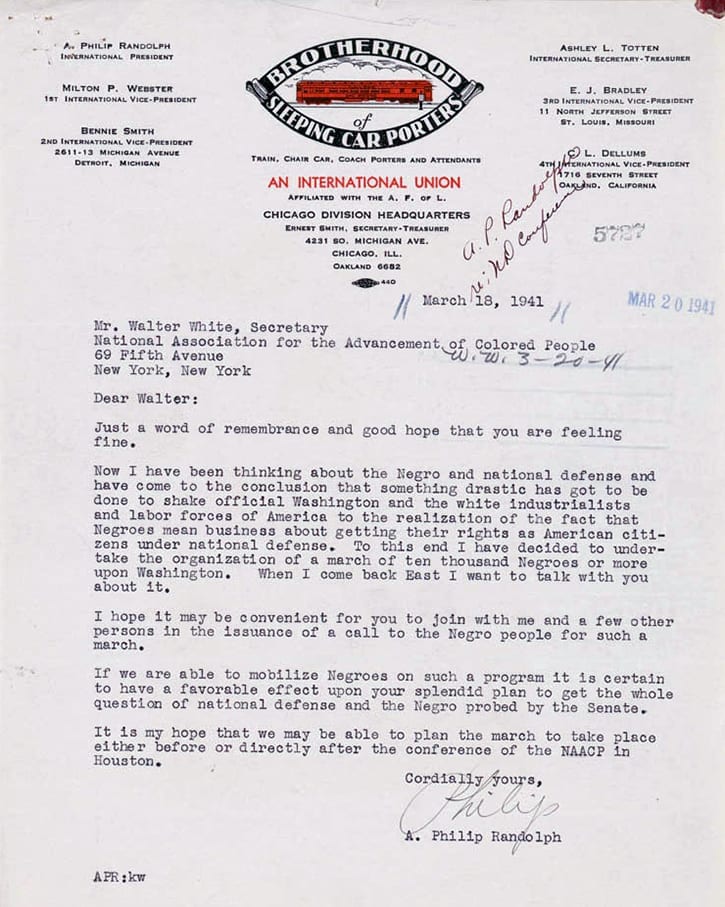

In 1938, Congress passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) as part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal program. Among other things, the AAA sought to stabilize the price of wheat by controlling the volume moving in interstate and foreign commerce. The secretary of agriculture was directed to proclaim each year a national acreage allotment for the next crop of wheat, which was then apportioned to the states and their counties and was eventually broken up into allotments for individual farms. In 1941, the AAA was amended to include the assessment of penalties against farmers who produced more than their allotment of wheat.

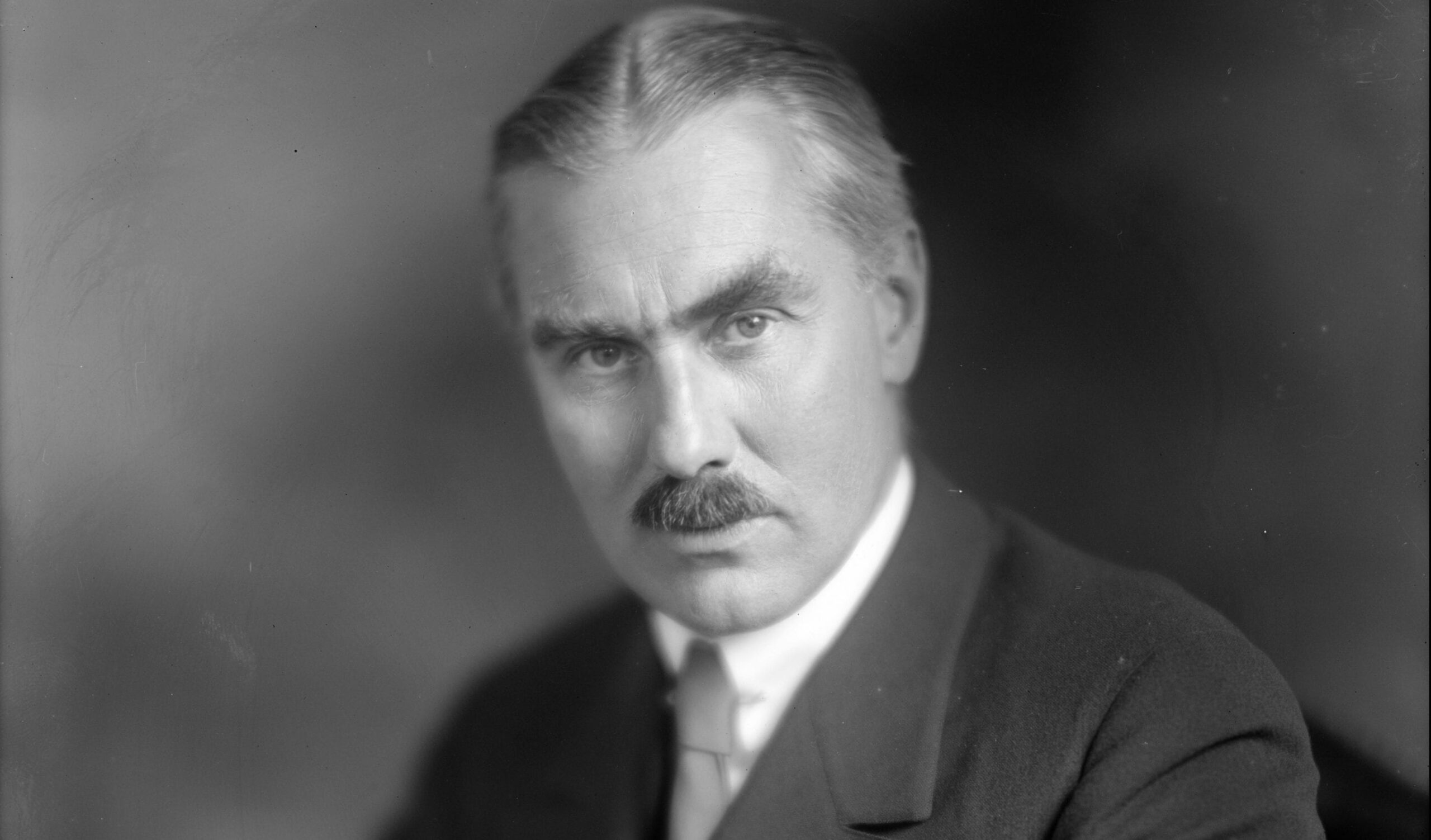

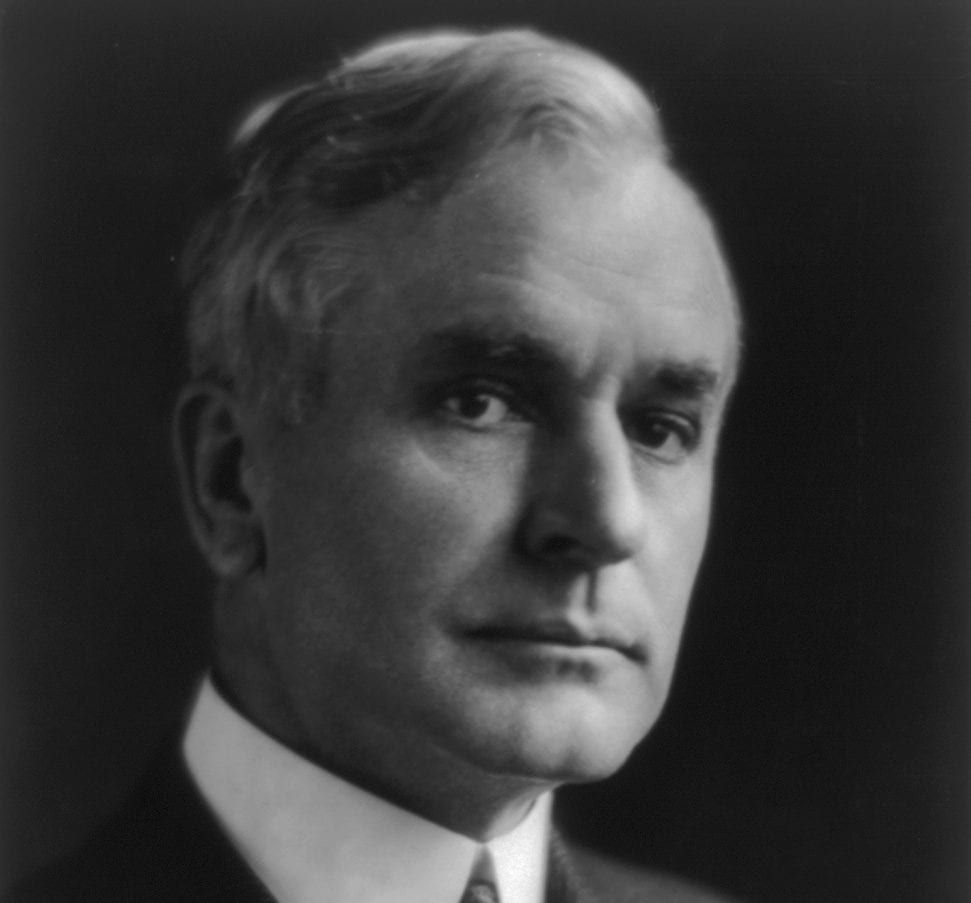

Roscoe Filburn owned and operated a small farm in Montgomery County, Ohio, maintaining a herd of dairy cattle, selling milk, raising poultry, and selling poultry and eggs. In 1941 Filburn was given a wheat acreage allotment of 11.1 acres and a normal yield of 20.1 bushels of wheat an acre. He sowed 23 acres, however, and harvested 239 extra bushels of wheat from his excess 11.9 acres. Under the terms of the AAA, this constituted farm marketing excess, subject to a penalty of 49 cents a bushel ($117.11 in total). Filburn refused to pay the penalty and sued Secretary of Agriculture Claude Wickard, arguing among other things that the application of the AAA’s penalty against him went beyond Congress’ power to regulate interstate commerce because, given the small size of Filburn’s farm, it did not have a close and substantial relation to such commerce.

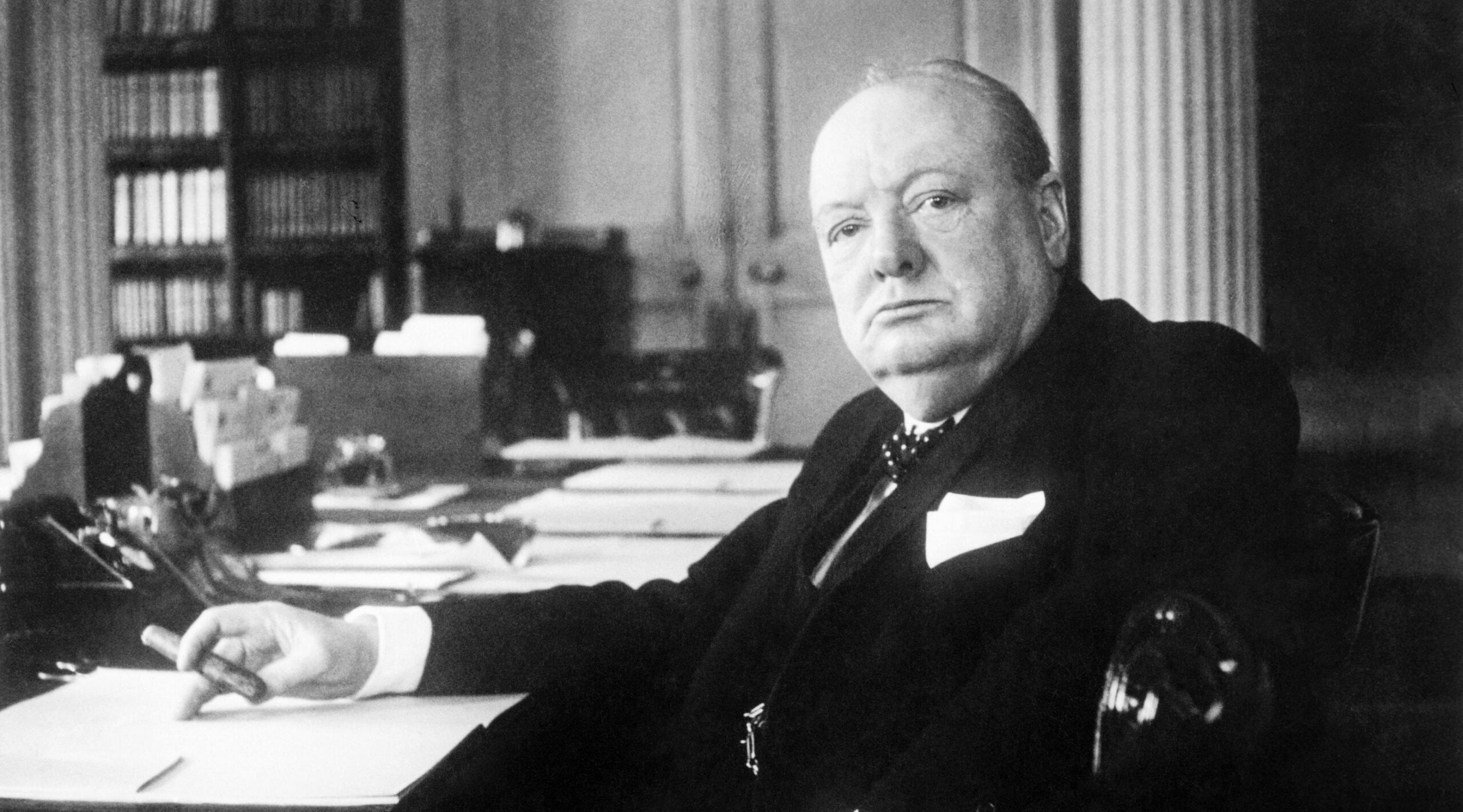

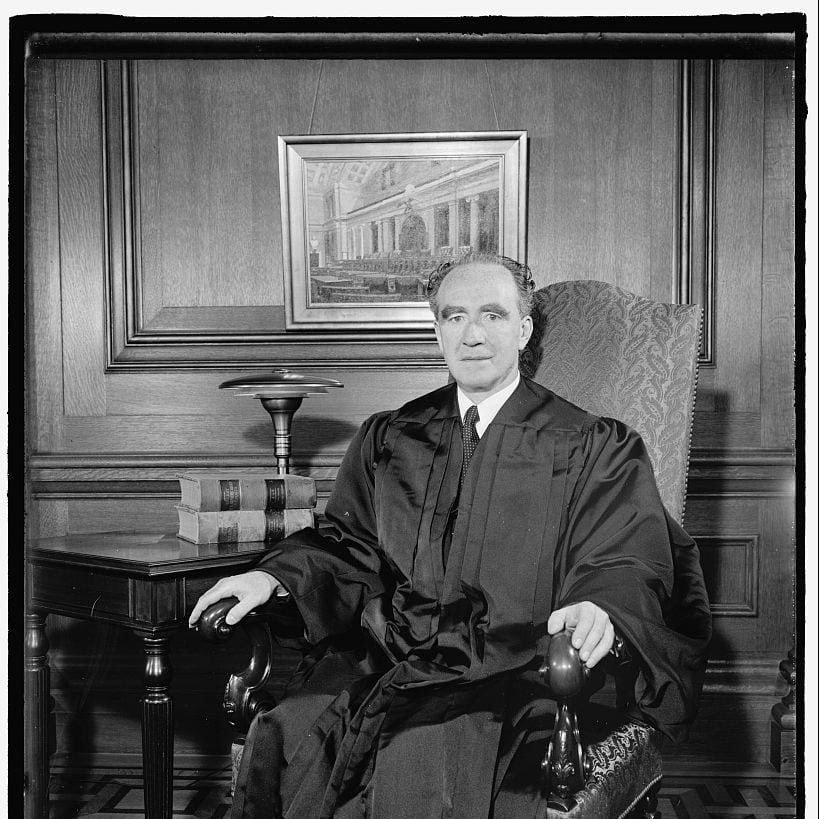

In a unanimous decision in favor of Secretary Wickard, the Supreme Court—including eight FDR appointees—explicitly rejected previous decisions like United States v. E. C. Knight (1895) and even went beyond the recent decision in NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin (1937). The Court declared that Congress has the power to regulate local economic production that, in the aggregate, has a substantial effect on interstate commerce, even if that local production is not directed to such commerce. The decision incorporated principles of “legal realism” that had been gaining acceptance since the early twentieth century. Legal realists argued that Congress’ commerce power should be interpreted not through an “abstract constitutional formula” but based on the real economic and social conditions of the country. Wickard v. Filburn is considered the Court’s most expansive reading of Congress’ interstate commerce power and has served as a broad precedent for direct congressional regulation of economic activity to the present day. In fact, the Supreme Court did not strike down another major federal law on commerce clause grounds until United States v. Lopez (1995), more than fifty years later.

Source: 317 U.S. 111; https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/317/111.

Justice JACKSON delivered the unanimous opinion of the Court, joined by Chief Justice STONE and Justices ROBERTS, BLACK, REED, FRANKFURTER, DOUGLAS, MURPHY, AND BYRNES.

. . .It is urged that, under the commerce clause of the Constitution, Article I, section 8, clause 3, Congress does not possess the power it has in this instance sought to exercise. . . .[The] marketing quotas not only embrace all that may be sold without penalty, but also what may be consumed on the premises. Wheat produced on excess acreage is designated as “available for marketing” as so defined, and the penalty is imposed thereon. Penalties do not depend upon whether any part of the wheat, either within or without the quota, is sold or intended to be sold. . . .

[Mr. Filburn] says that this is a regulation of production and consumption of wheat. Such activities are, he urges, beyond the reach of congressional power under the commerce clause, since they are local in character, and their effects upon interstate commerce are, at most, “indirect.” In answer, the government argues that the statute regulates neither production nor consumption, but only marketing, and, in the alternative, that if the act does go beyond the regulation of marketing, it is sustainable as a “necessary and proper” implementation of the power of Congress over interstate commerce.

The government’s concern lest the act be held to be a regulation of production or consumption, rather than of marketing, is attributable to a few dicta and decisions of this Court which might be understood to lay it down that activities such as “production,” “manufacturing,” and “mining” are strictly “local” and, except in special circumstances which are not present here, cannot be regulated under the commerce power because their effects upon interstate commerce are, as matter of law, only “indirect.” Even today, when this power has been held to have great latitude, there is no decision of this Court that such activities may be regulated where no part of the product is intended for interstate commerce or intermingled with the subjects thereof. We believe that a review of the course of decision under the commerce clause will make plain, however, that questions of the power of Congress are not to be decided by reference to any formula which would give controlling force to nomenclature such as “production” and “indirect” and foreclose consideration of the actual effects of the activity in question upon interstate commerce.

At the beginning, Chief Justice Marshall described the federal commerce power with a breadth never yet exceeded (see Gibbons v. Ogden (1824)). He made emphatic the embracing and penetrating nature of this power by warning that effective restraints on its exercise must proceed from political, rather than from judicial, processes. . . .

It was not until 1887, with the enactment of the Interstate Commerce Act, that the interstate commerce power began to exert positive influence in American law and life. This first important federal resort to the commerce power was followed in 1890 by the Sherman Antitrust Act and, thereafter, mainly after 1903, by many others. These statutes ushered in new phases of adjudication, which required the Court to approach the interpretation of the commerce clause in the light of an actual exercise by Congress of its power thereunder.

When it first dealt with this new legislation, the Court adhered to its earlier pronouncements, and allowed but little scope to the power of Congress (see United States v. E. C. Knight Co.)….

Even while important opinions in this line of restrictive authority were being written, however, other cases called forth broader interpretations of the commerce clause destined to supersede the earlier ones, and to bring about a return to the principles first enunciated by Chief Justice Marshall in Gibbons v. Ogden.

Not long after the decision of United States v. E. C. Knight Co.,…[i]t was soon demonstrated that the effects of many kinds of intrastate activity upon interstate commerce were such as to make them a proper subject of federal regulation. In some cases sustaining the exercise of federal power over intrastate matters, the term “direct” was used for the purpose of stating, rather than of reaching, a result; in others it was treated as synonymous with “substantial” or “material”; and in others it was not used at all. Of late, its use has been abandoned in cases dealing with questions of federal power under the commerce clause. . . .

The Court’s recognition of the relevance of the economic effects in the application of the commerce clause . . . has made the mechanical application of legal formulas no longer feasible. Once an economic measure of the reach of the power granted to Congress in the commerce clause is accepted, questions of federal power cannot be decided simply by finding the activity in question to be “production,” nor can consideration of its economic effects be foreclosed by calling them “indirect.”. . .

Whether the subject of the regulation in question was “production,” “consumption,” or “marketing” is, therefore, not material for purposes of deciding the question of federal power before us. That an activity is of local character may help in a doubtful case to determine whether Congress intended to reach it. The same consideration might help in determining whether, in the absence of congressional action, it would be permissible for the state to exert its power on the subject matter, even though, in so doing, it to some degree affected interstate commerce. But even if [Filburn’s] activity be local, and though it may not be regarded as commerce, it may still, whatever its nature, be reached by Congress if it exerts a substantial economic effect on interstate commerce, and this irrespective of whether such effect is what might at some earlier time have been defined as “direct” or “indirect.”

The parties have stipulated a summary of the economics of the wheat industry. Commerce among the states in wheat is large and important. . . .

The wheat industry has been a problem industry for some years. Largely as a result of increased foreign production and import restrictions, annual exports of wheat and flour from the United States during the ten-year period ending in 1940 averaged less than 10 percent of total production, while, during the 1920s they averaged more than 25 percent. The decline in the export trade has left a large surplus in production which, in connection with an abnormally large supply of wheat and other grains in recent years, caused congestion in a number of markets; tied up railroad cars; and caused elevators in some instances to turn away grains, and railroads to institute embargoes to prevent further congestion. . . .

In the absence of regulation, the price of wheat in the United States would be much affected by world conditions. During 1941, producers who cooperated with the Agricultural Adjustment program received an average price on the farm of about $1.16 a bushel, as compared with the world market price of 40 cents a bushel. . . .

The maintenance by government regulation of a price for wheat undoubtedly can be accomplished as effectively by sustaining or increasing the demand as by limiting the supply. The effect of the statute before us is to restrict the amount which may be produced for market and the extent as well to which one may forestall resort to the market by producing to meet his own needs. That [Filburn’s] own contribution to the demand for wheat may be trivial by itself is not enough to remove him from the scope of federal regulation where, as here, his contribution, taken together with that of many others similarly situated, is far from trivial.

It is well established by decisions of this Court that the power to regulate commerce includes the power to regulate the prices at which commodities in that commerce are dealt in and practices affecting such prices. One of the primary purposes of the act in question was to increase the market price of wheat, and, to that end, to limit the volume thereof that could affect the market. It can hardly be denied that a factor of such volume and variability as home-consumed wheat would have a substantial influence on price and market conditions. This may arise because being in marketable condition such wheat overhangs the market, and, if induced by rising prices, tends to flow into the market and check price increases. But if we assume that it is never marketed, it supplies a need of the man who grew it which would otherwise be reflected by purchases in the open market. Home-grown wheat in this sense competes with wheat in commerce. The stimulation of commerce is a use of the regulatory function quite as definitely as prohibitions or restrictions thereon. This record leaves us in no doubt that Congress may properly have considered that wheat consumed on the farm where grown, if wholly outside the scheme of regulation, would have a substantial effect in defeating and obstructing its purpose to stimulate trade therein at increased prices.

It is said, however, that this act, forcing some farmers into the market to buy what they could provide for themselves, is an unfair promotion of the markets and prices of specializing wheat growers. It is of the essence of regulation that it lays a restraining hand on the self-interest of the regulated, and that advantages from the regulation commonly fall to others. The conflicts of economic interest between the regulated and those who advantage by it are wisely left under our system to resolution by the Congress under its more flexible and responsible legislative process. Such conflicts rarely lend themselves to judicial determination. And with the wisdom, workability, or fairness, of the plan of regulation, we have nothing to do. . . .

Reversed.

Wickard v. Filburn

November 09, 1942

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.