Introduction

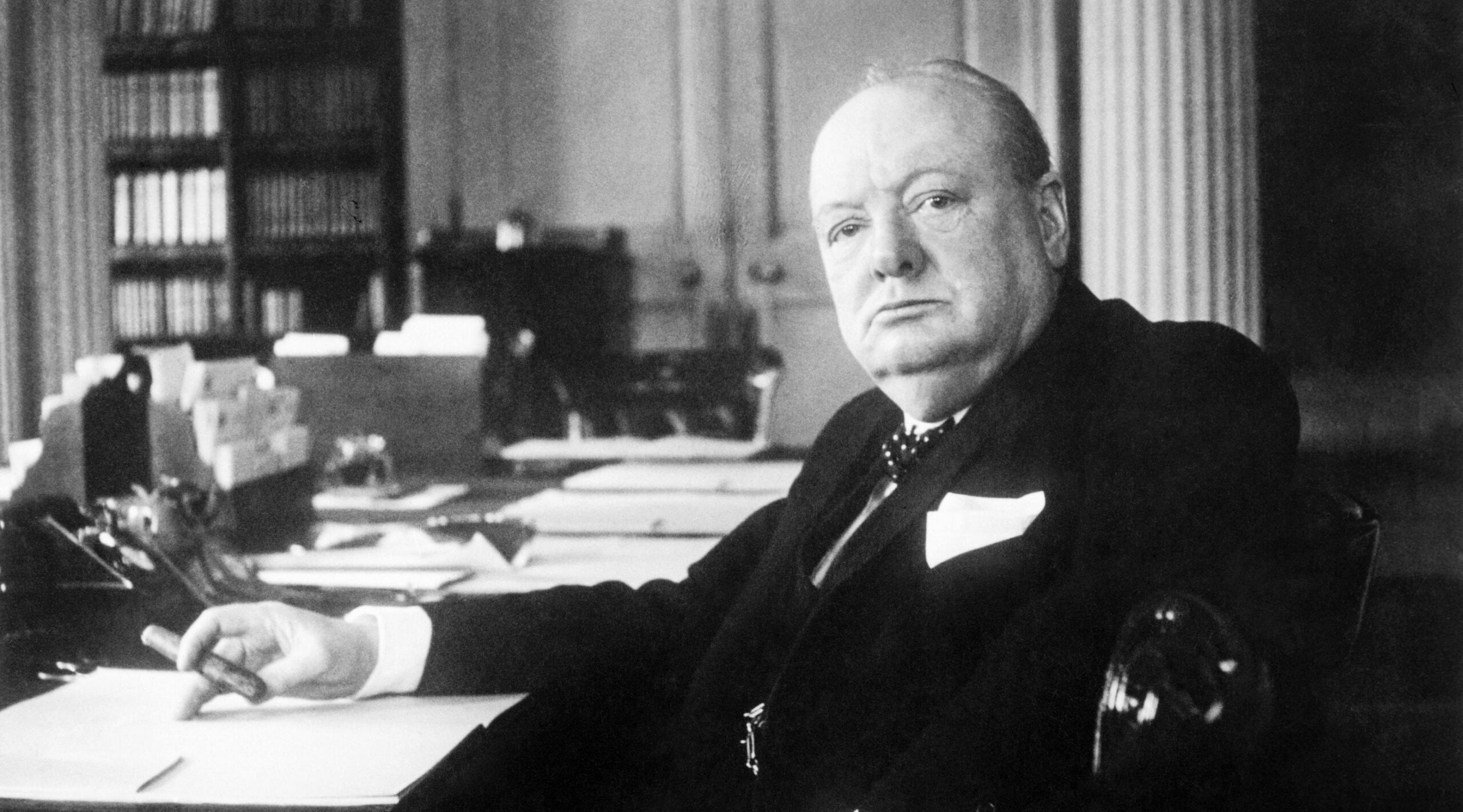

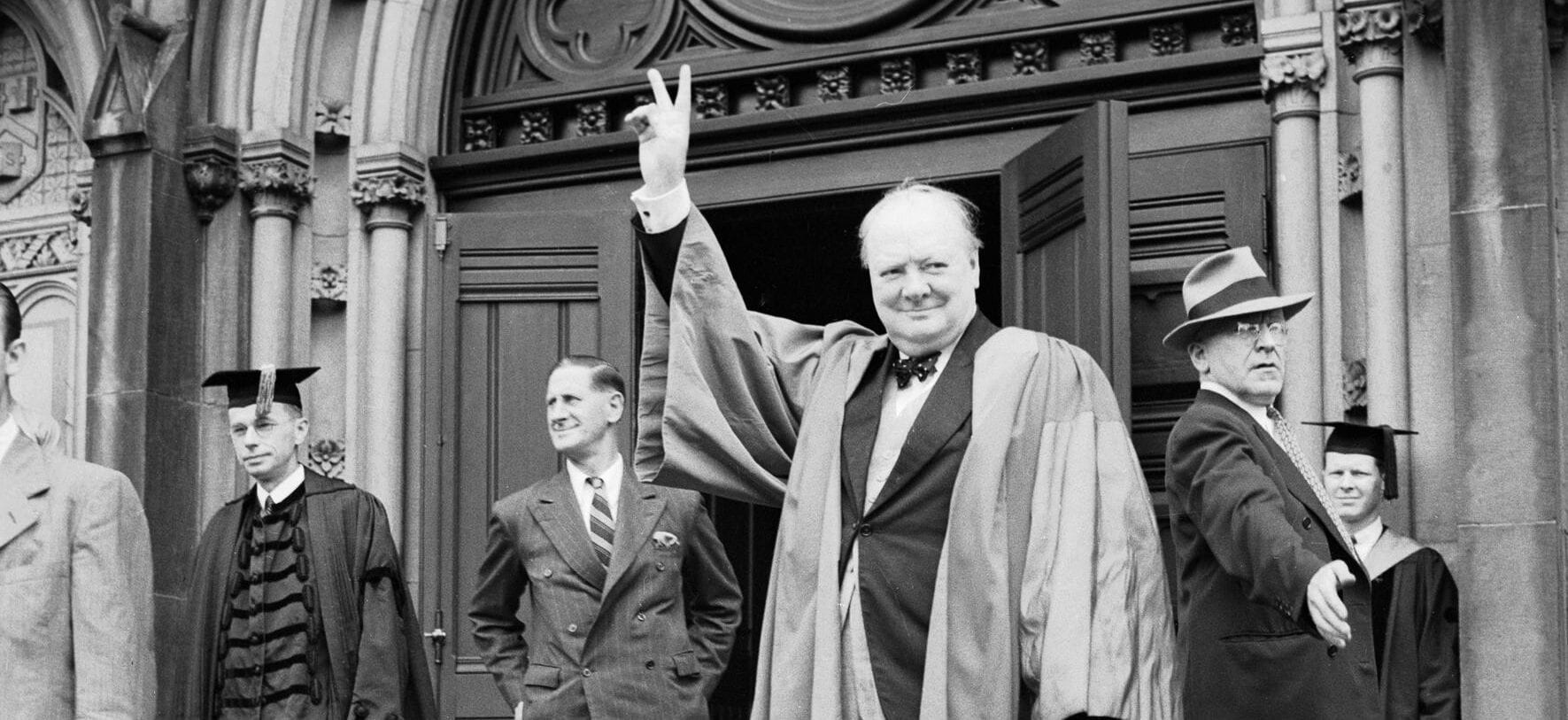

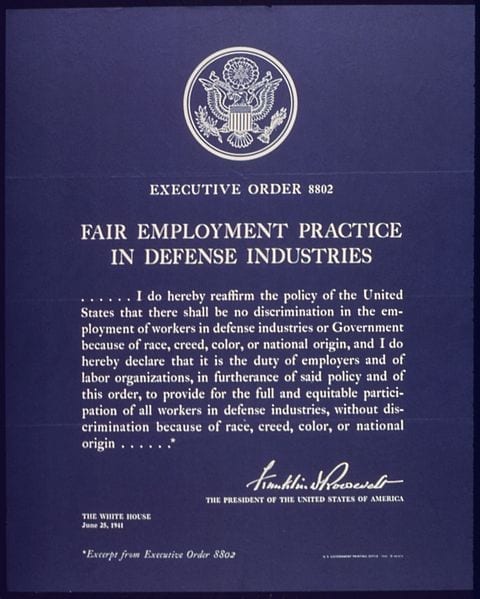

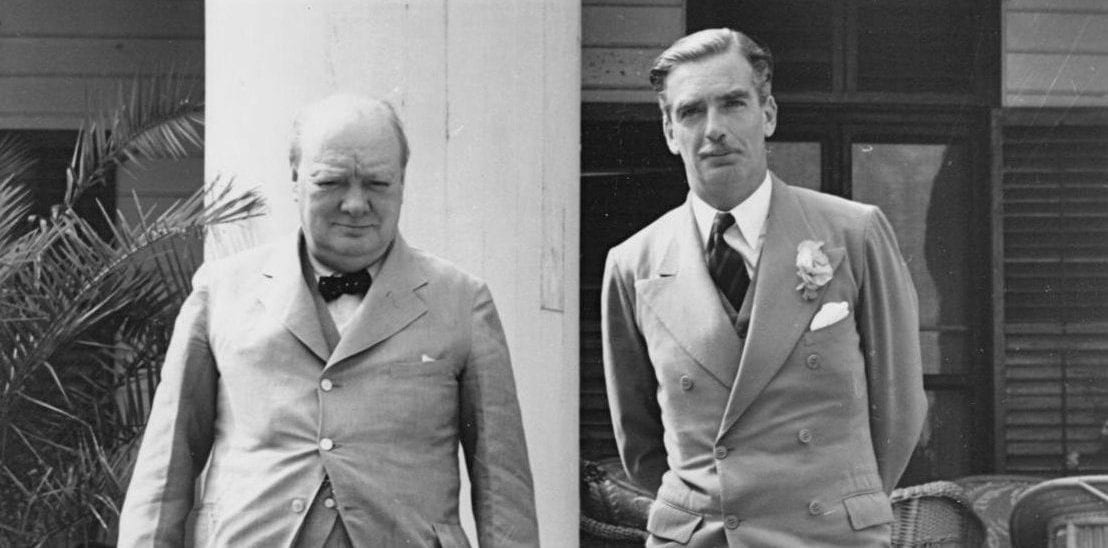

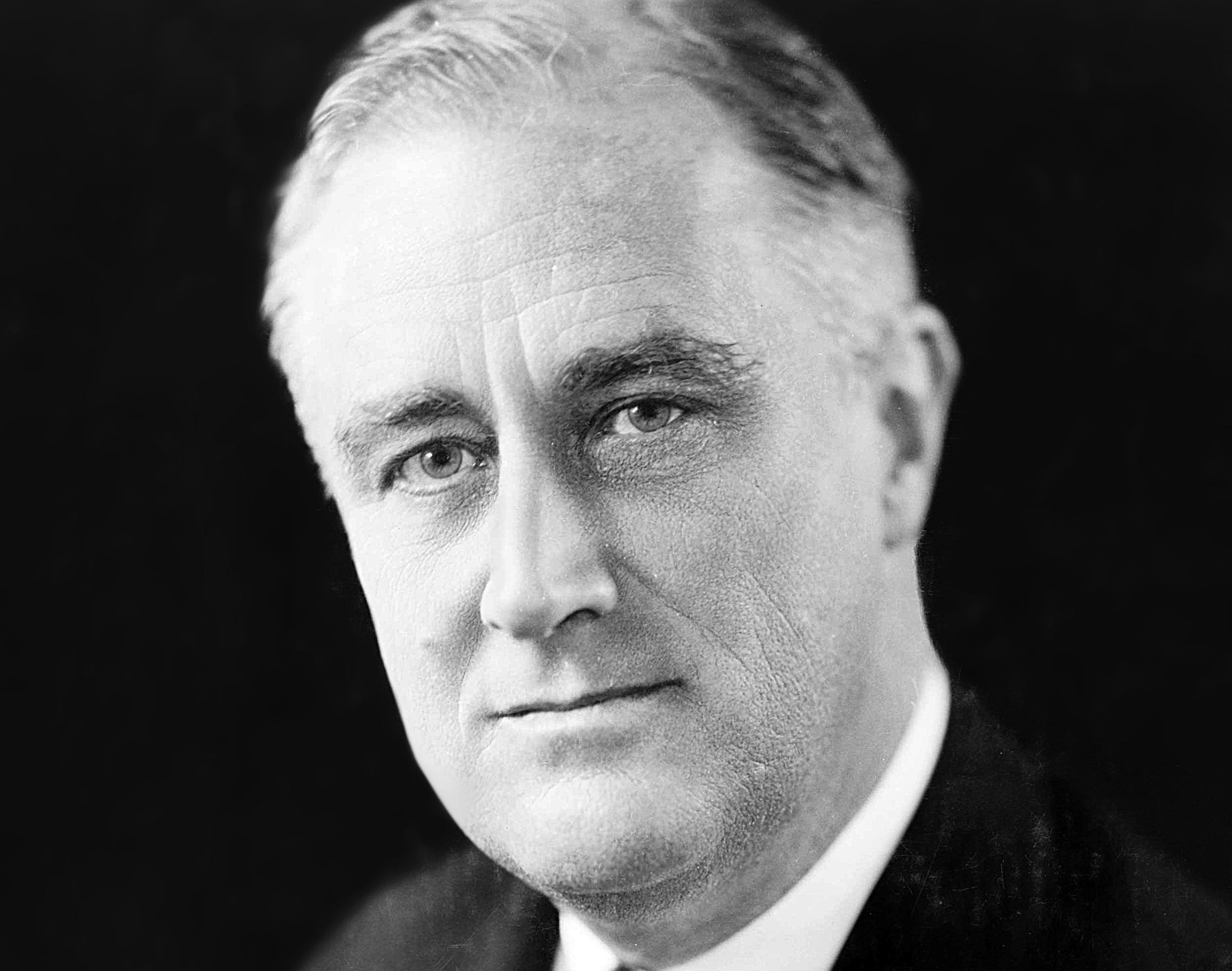

When World War II began in 1939, President Roosevelt tried and failed to get a complete repeal of the Neutrality Laws. Instead, Congress passed the 1939 Neutrality Law that expanded trade with warring nations on a “cash and carry” basis (nations at war were now permitted to purchase war related goods and had to transport them in their own ships). The new law, however, retained the ban on war loans to warring nations. By 1940, this provision threatened to shut down trade with Britain, which needed credit to continue buying munitions, raw materials, and food from the United States. In response, Roosevelt devised Lend-Lease. FDR laid the groundwork for Lend-Lease in September 1940 when he negotiated the bases-for-destroyers deal with Britain, trading 50 U.S. naval destroyers for leases on bases in British-held territories in Newfoundland, the Bahamas, and Caribbean. In this December 17, 1940 press conference, Roosevelt described how Lend-Lease would work and defended it as consistent with the Neutrality Law. Congress passed the Lend-Lease Act in March 1941.

Source: Franklin D. Roosevelt: “Press Conference,” December 17, 1940. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. https://goo.gl/U33U33.

The President: . . . In the present world situation of course there is absolutely no doubt in the mind of a very overwhelming number of Americans that the best immediate defense of the United States is the success of Great Britain in defending itself; and that, therefore, quite aside from our historic and current interest in the survival of democracy, in the world as a whole, it is equally important from a selfish point of view of American defense, that we should do everything to help the British Empire to defend itself. . . .

I remember 1914 very well, and I will give you an illustration: In 1914 I was up at Eastport, Maine, with the family the end of July, and I got a telegram from the Navy Department that it looked as if war would break out in Europe the next day.1 Actually it did break out in a few hours, when Germany invaded Belgium. So I went across from the island and took a train down to Ellsworth, where I got on the Bar Harbor Express. I went into the smoking room. The smoking room of the Express was filled with gentlemen from banking and brokerage offices in New York, most of whom were old friends of mine; and they began giving me their opinion about the impending world war in Europe. These eminent bankers and brokers assured me, and made it good with bets, that there wasn't enough money in all the world to carry on a European war for more than three months – bets at even money; that the bankers would stop the war within six months – odds of 2 to 1; that it was humanly impossible – physically impossible – for a European war to last for six months – odds of 4 to 1; and so forth and so on. Well, actually, I suppose I must have won those – they were small, five-dollar bets – I must have made a hundred dollars. I wish I had bet a lot more.

There was the best economic opinion in the world that the continuance of war was absolutely dependent on money in the bank. Well, you know what happened. . . .

Orders from Great Britain are therefore a tremendous asset to American national defense; because they automatically create additional facilities. I am talking selfishly, from the American point of view – nothing else. Therefore, from the selfish point of view, that production must be encouraged by us. There are several ways of encouraging it – not just one, as the narrow-minded fellow I have been talking about might assume, and has assumed. He has assumed that the only way was to repeal certain existing statutes, like the Neutrality Act and the old Johnson Act2 and a few other things like that; and then to lend the money to Great Britain to be spent over here – either lend it through private banking circles, as was done in the earlier days of the previous war, or make it a loan from this Government to the British Government.

Well, that is one type of mind that can think only of that method[, which is] somewhat banal.

There is another one which is also somewhat banal – we may come to it, I don't know – and that is a gift; in other words, for us to pay for all these munitions, ships, plants, guns, et cetera, and make a gift of them to Great Britain. I am not at all sure that that is a necessity, and I am not at all sure that Great Britain would care to have a gift from the taxpayers of the United States. I doubt it very much.

Well, there are other possible ways, and those ways are being explored. All I can do is to speak in very general terms, because we are in the middle of it. I have been at it now three or four weeks, exploring other methods of continuing the building up of our productive facilities and continuing automatically the flow of munitions to Great Britain. I will just put it this way, not as an exclusive alternative method, but as one of several other possible methods that might be devised toward that end.

It is possible – I will put it that way – for the United States to take over British orders, and, because they are essentially the same kind of munitions that we use ourselves, turn them into American orders. We have enough money to do it. And thereupon, as to such portion of them as the military events of the future determine to be right and proper for us to allow to go to the other side, either lease or sell the materials, subject to mortgage, to the people on the other side. That would be on the general theory that it may still prove true that the best defense of Great Britain is the best defense of the United States, and therefore that these materials would be more useful to the defense of the United States if they were used in Great Britain, than if they were kept in storage here.

Now, what I am trying to do is to eliminate the dollar sign. That is something brand new in the thoughts of practically everybody in this room, I think – get rid of the silly, foolish old dollar sign.

Well, let me give you an illustration: Suppose my neighbor's home catches fire, and I have a length of garden hose four or five hundred feet away. If he can take my garden hose and connect it up with his hydrant, I may help him to put out his fire. Now, what do I do? I don't say to him before that operation, “Neighbor, my garden hose cost me $15; you have to pay me $15 for it.” What is the transaction that goes on? I don't want $15 – I want my garden hose back after the fire is over. All right. If it goes through the fire all right, intact, without any damage to it, he gives it back to me and thanks me very much for the use of it. But suppose it gets smashed up – holes in it – during the fire; we don't have to have too much formality about it, but I say to him, “I was glad to lend you that hose; I see I can't use it any more, it's all smashed up.” He says, “How many feet of it were there?” I tell him, “There were 150 feet of it.” He says, “All right, I will replace it.” Now, if I get a nice garden hose back, I am in pretty good shape.

In other words, if you lend certain munitions and get the munitions back at the end of the war, if they are intact, haven't been hurt – you are all right; if they have been damaged or have deteriorated or have been lost completely, it seems to me you come out pretty well if you have them replaced by the fellow to whom you have lent them.

I can’t go into details; and there is no use asking legal questions about how you would do it, because that is the thing that is now under study; but the thought is that we would take over not all, but a very large number of, future British orders; and when they came off the line, whether they were planes or guns or something else, we would enter into some kind of arrangement for their use by the British on the ground that it was the best thing for American defense, with the understanding that when the show was over, we would get repaid sometime in kind, thereby leaving out the dollar mark in the form of a dollar debt and substituting for it a gentleman's obligation to repay in kind. I think you all get it. . . .

Arsenal of Democracy Fireside Chat

December 29, 1940

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.