Introduction

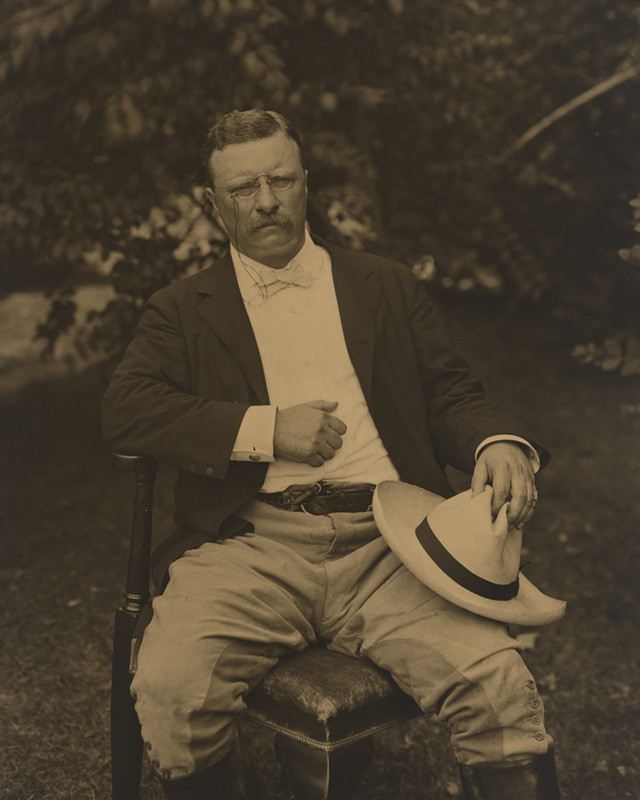

In 1912, U.S. senator, former Wisconsin governor, and progressive reformer Robert La Follette (1855–1925) challenged incumbent William Howard Taft (1857–1930) for the Republican Party presidential nomination. La Follette sought to represent the more progressive elements of the Republican Party against Taft’s constitutional conservatism. Former president Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) had seen Taft as his handpicked successor. By 1912, however, Roosevelt believed Taft had strayed from progressive principles, and he entered the race to challenge both Taft and La Follette for the nomination. In an effort to counter La Follette and attract progressive voters, Roosevelt delivered the following address at New York’s Carnegie Hall early in the campaign. Roosevelt defended the introduction of more directly democratic procedures into American politics. In particular, he advocated progressive reforms such as the direct primary election, initiative, referendum, the recall of public officials, and the popular recall of judicial decisions. Roosevelt defended such mechanisms not merely on the basis of pragmatic, political concerns, but on the level of principle; that is, as an inference from the very notion of popular sovereignty.

Roosevelt’s criticism of the courts is especially noteworthy here. The Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibits the federal government from denying any person life, liberty, or property without due process of law. The Fourteenth Amendment applies that same prohibition to state governments. Traditionally, “due process” meant that governments had to follow certain formal procedures if they sought to deprive individuals of life, liberty, or property. This might include, for example, the right of an individual to be notified of the government’s intentions, the right to counsel, and the right to a hearing. At the turn of the twentieth century, however, American courts began to hold that due process required protection of certain inherent, substantive rights apart from formal legal procedures. During the progressive era, courts argued that the rights afforded by this “substantive due process” were often economic, such as property rights and an implied freedom of contract. State and federal courts sometimes used this reasoning to strike down progressive legislation regulating working conditions, minimum wage laws, and workers’ compensation protections, among other things. See, for example, Matter of Application of Jacobs, 98 N.Y. 98 (1885); Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905); and Ives v. South Buffalo Railway Company, 201 N.Y. 271 (1911). Roosevelt’s proposals for the recall of judicial decisions aimed at combatting what he saw as faulty judicial interpretations of due process.

Source: Theodore Roosevelt, “The Right of the People to Rule,” Outlook 100 (March 1912): 618–23, available online at the Hathi Trust Digital Library: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015026764921&view=1up&seq=660.

The great fundamental issue now before the Republican Party and before our people can be stated briefly. It is: Are the American people fit to govern themselves, to rule themselves, to control themselves? I believe they are. My opponents do not. I believe in the right of the people to rule. I believe the majority of the plain people of the United States will, day in and day out, make fewer mistakes in governing themselves than any smaller class or body of men, no matter what their training, will make in trying to govern them. I believe, again, that the American people are, as a whole, capable of self-control and of learning by their mistakes. Our opponents pay lip-loyalty to this doctrine; but they show their real beliefs by the way in which they champion every device to make the nominal rule of the people a sham.

I have scant patience with this talk of the tyranny of the majority. Wherever there is tyranny of the majority, I shall protest against it with all my heart and soul. But we are today suffering from the tyranny of minorities. It is a small minority that is grabbing our coal deposits, our water powers, and our harbor fronts. A small minority is battening on the sale of adulterated foods and drugs. It is a small minority that lies behind monopolies and trusts. It is a small minority that stands behind the present law of master and servant, the sweatshops, and the whole calendar of social and industrial injustice. It is a small minority that is today using our convention system to defeat the will of a majority of the people in the choice of delegates to the Chicago Convention.[1] The only tyrannies from which men, women, and children are suffering in real life are the tyrannies of minorities. If the majority of the American people were in fact tyrannous over the minority, if democracy had no greater self-control than empire, then indeed no written words which our forefathers put into the Constitution could stay that tyranny.

No sane man who has been familiar with the government of this country for the last twenty years will complain that we have had too much of the rule of the majority. The trouble has been a far different one that, at many times and in many localities, there have held public office in the states and in the nation men who have, in fact, served not the whole people, but some special class or special interest. . . .

Now there has sprung up a feeling deep in the hearts of the people—not of the bosses and professional politicians, not of the beneficiaries of special privilege—a pervading belief of thinking men that when the majority of the people do in fact, as well as theory, rule, then the servants of the people will come more quickly to answer and obey, not the commands of the special interests, but those of the whole people. To reach toward that end the progressives of the Republican Party in certain states have formulated certain proposals for change in the form of the state government—certain new “checks and balances” which may check and balance the special interests and their allies. That is their purpose. Now, turn for a moment to their proposed methods.

First, there are the “initiative and referendum,” which are so framed that if the legislatures obey the command of some special interest, and obstinately refuse the will of the majority, the majority may step in and legislate directly. No man would say that it was best to conduct all legislation by direct vote of the people—it would mean the loss of deliberation, of patient consideration—but, on the other hand, no one whose mental arteries have not long since hardened can doubt that the proposed changes are needed when the legislatures refuse to carry out the will of the people. The proposal is a method to reach an undeniable evil. Then there is the recall of public officers, the principle that an officer chosen by the people who is unfaithful may be recalled by vote of the majority before he finishes his term. I will speak of the recall of judges in a moment—leave that aside—but as to the other officers, I have heard no argument advanced against the proposition, save that it will make the public officer timid and always currying favor with the mob. That argument means that you can fool all the people all the time, and is an avowal of disbelief in democracy. If it be true—and I believe it is not—it is less important than to stop those public officers from currying favor with the interests. Certain states may need the recall, others may not; where the term of elective office is short it may be quite needless; but there are occasions when it meets a real evil, and provides a needed check and balance against the special interests.

Then there is the direct primary—the real one, not the New York one—and that, too, the progressives offer as a check on the special interests.[2] Most clearly of all does it seem to me that this change is wholly good for every state. The system of party government is not written in our Constitutions, but it is none the less a vital and essential part of our form of government. In that system the party leaders should serve and carry out the will of their own party. . . . The direct primary will give the voters a method ever ready to use, by which the party leader shall be made to obey their command. The direct primary, if accompanied by a stringent corrupt-practices act, will help break up the corrupt partnership of corporations and politicians.

My opponents charge that two things in my program are wrong because they intrude into the sanctuary of the judiciary. The first is the recall of judges; and the second, the review by the people of judicial decisions on certain constitutional questions. I have said again and again that I do not advocate the recall of judges in all states and in all communities. In my own state I do not advocate it or believe it to be needed, for in this state our trouble lies not with corruption on the bench, but with the effort by the honest but wrong-headed judges to thwart the people in their struggle for social justice and fair dealing. The integrity of our judges . . . is a fine page of American history. But—I say it soberly—democracy has a right to approach the sanctuary of the courts when a special interest has corruptly found sanctuary there; and this is exactly what has happened in some of the states where the recall of the judges is a living issue. I would far more willingly trust the whole people to judge such a case than some special tribunal—perhaps appointed by the same power that chose the judge—if that tribunal is not itself really responsible to the people and is hampered and clogged by the technicalities of impeachment proceedings.

I have stated that the courts of the several states—not always but often—have construed the “due process” clause of the state constitutions as if it prohibited the whole people of the state from adopting methods of regulating the use of property so that human life, particularly the lives of the workingmen, shall be safer, freer, and happier. No one can successfully impeach this statement. I have insisted that the true construction of “due process” is that pronounced by Justice Holmes[3] in delivering the unanimous opinion of the Supreme Court of the United States, when he said: “The police power extends to all the great public needs. It may be put forth in aid of what is sanctioned by usage, or held by the prevailing morality or strong and preponderant opinion to be greatly and immediately necessary to the public welfare.”[4]

I insist that the decision of the New York Court of Appeals in the Ives case, which set aside the will of the majority of the people as to the compensation of injured workmen in dangerous trades, was intolerable and based on a wrong political philosophy.[5] I urge that in such cases where the courts construe the due process clause as if property rights, to the exclusion of human rights, had a first mortgage on the Constitution, the people may, after sober deliberation, vote, and finally determine whether the law which the court set aside shall be valid or not. By this method can be clearly and finally ascertained the preponderant opinion of the people which Justice Holmes makes the test of due process in the case of laws enacted in the exercise of the police power. The ordinary methods now in vogue of amending the Constitution have in actual practice proved wholly inadequate to secure justice in such cases with reasonable speed, and cause intolerable delay and injustice, and those who stand against the changes I propose are champions of wrong and injustice, and of tyranny by the wealthy and the strong over the weak and the helpless.

So that no man may misunderstand me, let me recapitulate:

(1) I am not proposing anything in connection with the Supreme Court of the United States, or with the federal Constitution.

(2) I am not proposing anything having any connection with ordinary suits, civil or criminal, as between individuals.

(3) I am not speaking of the recall of judges.

(4) I am proposing merely that in a certain class of cases involving police power, when a state court has set aside as unconstitutional a law passed by the legislature for the general welfare, the question of the validity of the law—which should depend, as Justice Holmes so well phrases it, upon the prevailing morality or preponderant opinion—be submitted for final determination to a vote of the people, taken after due time for consideration. And I contend that the people, in the nature of things, must be better judges of what is the preponderant opinion than the courts, and that the courts should not be allowed to reverse the political philosophy of the people. My point is well illustrated by a recent decision of the Supreme Court, holding that the Court would not take jurisdiction of a case involving the constitutionality of the initiative and referendum laws of Oregon. The ground of the decision was that such a question was not judicial in its nature, but should be left for determination to the other coordinate departments of the government.[6] Is it not equally plain that the question whether a given social policy is for the public good is not of a judicial nature, but should be settled by the legislature, or in the final instance by the people themselves?

The president of the United States, Mr. Taft, devoted most of a recent speech to criticism of this proposition. He says that it “is utterly without merit or utility, and, instead of being in the interest of all the people, and of the stability of popular government, is sowing the seeds of confusion and tyranny.” (By this he, of course, means the tyranny of the majority; that is, the tyranny of the American people as a whole.) He also says that my proposal (which, as he rightly sees, is merely a proposal to give the people a real, instead of only a nominal, chance to construe and amend a state constitution with reasonable rapidity) would make such amendment and interpretation “depend on the feverish, uncertain, and unstable determination of successive votes on different laws by temporary and changing majorities”; and that “it lays the axe at the root of the tree of well-ordered freedom, and subjects the guaranties of life, liberty, and property without remedy to the fitful impulse of a temporary majority of an electorate.”[7]

This criticism is really less a criticism of my proposal than a criticism of all popular government. It is wholly unfounded, unless it is founded on the belief that the people are fundamentally untrustworthy. If the Supreme Court’s definition of due process in relation to the police power is sound, then an act of the legislature to promote the collective interests of the community must be valid, if it embodies a policy held by the prevailing morality or a preponderant opinion to be necessary to the public welfare. This is the question that I propose to submit to the people. How can the prevailing morality or a preponderant opinion be better and more exactly ascertained than by a vote of the people? The people must know better than the court what their own morality and their own opinion is. . . .

The object I have in view could probably be accomplished by an amendment of the state constitutions taking away from the courts the power to review the legislature’s determination of a policy of social justice, by defining due process of law in accordance with the views expressed by Justice Holmes of the Supreme Court. But my proposal seems to me more democratic and, I may add, less radical. For under the method I suggest the people may sustain the court as against the legislature, whereas, if due process were defined in the Constitution, the decision of the legislature would be final.

Mr. Taft’s position is the position that has been held from the beginning of our government, although not always so openly held, by a large number of reputable and honorable men who, down at bottom, distrust popular government, and, when they must accept it, accept it with reluctance, and hedge it around with every species of restriction and check and balance, so as to make the power of the people as limited and as ineffective as possible. Mr. Taft fairly defines the issue when he says that our government is and should be a government of all the people by a representative part of the people. This is an excellent and moderate description of all oligarchy. It defines our government as a government of all the people by a few of the people. . . .

. . . Mr. Taft says that “every class” should have a “voice” in the government. That seems to me a very serious misconception of the American political situation. The real trouble with us is that some classes have had too much voice. One of the most important of all the lessons to be taught and to be learned is that a man should vote, not as a representative of a class, but merely as a good citizen, whose prime interests are the same as those of all other good citizens. The belief in different classes, each having a voice in the government, has given rise to much of our present difficulty; for whosoever believes in these separate classes, each with a voice, inevitably, even although unconsciously, tends to work, not for the good of the whole people, but for the protection of some special class—usually that to which he himself belongs.

The same principle applies when Mr. Taft says that the judiciary ought not to be “representative” of the people in the sense that the legislature and the executive are. This is perfectly true of the judge when he is performing merely the ordinary functions of a judge in suits between man and man. It is not true of the judge engaged in interpreting, for instance, the due process clause—where the judge is ascertaining the preponderant opinion of the people (as Judge Holmes states it). When he exercises that function he has no right to let his political philosophy reverse and thwart the will of the majority. In that function the judge must represent the people or he fails in the test the Supreme Court has laid down. . . .

Mr. Taft again and again, in quotations I have given and elsewhere through his speech, expresses his disbelief in the people when they vote at the polls. In one sentence he says that the proposition gives “powerful effect to the momentary impulse of a majority of an electorate and prepares the way for the possible exercise of the grossest tyranny.” Elsewhere he speaks of the “feverish uncertainty” and “unstable determination” of laws by “temporary and changing majorities”; and again he says that the system I propose “would result in suspension or application of constitutional guaranties according to popular whim,” which would destroy “all possible consistency” in constitutional interpretation. I should much like to know the exact distinction that is to be made between what Mr. Taft calls “the fitful impulse of a temporary majority” when applied to a question such as that I raise and any other question. Remember that under my proposal to review a rule of decision by popular vote, amending or construing, to that extent, the Constitution, would certainly take at least two years from the time of the election of the legislature which passed the act. . . . It seems absurd to speak of a conclusion reached by the people after two years’ deliberation, after thrashing the matter out before the legislature, after thrashing it out before the governor, after thrashing it out before the court and by the court, and then after full debate for four or six months, as “the fitful impulse of a temporary majority.” If Mr. Taft’s language correctly describes such action by the people, then he himself and all other presidents have been elected by “the fitful impulse of a temporary majority”; then the constitution of each state, and the Constitution of the nation, have been adopted, and all amendments thereto have been adopted, by “the fitful impulse of a temporary majority.” If he is right, it was “the fitful impulse of a temporary majority” which founded, and another fitful impulse which perpetuated, this nation. Mr. Taft’s position is perfectly clear. It is that we have in this country a special class of persons wiser than the people, who are above the people, who cannot be reached by the people, but who govern them and ought to govern them; and who protect various classes of the people from the whole people. That is the old, old doctrine which has been acted upon for thousands of years abroad; and which here in America has been acted upon sometimes openly, sometimes secretly, for forty years by many men in public and in private life, and I am sorry to say by many judges; a doctrine which has in fact tended to create a bulwark for privilege, a bulwark unjustly protecting special interests against the rights of the people as a whole. . . .

Mr. Taft is very much afraid of the tyranny of majorities. For twenty-five years here in New York State, in our efforts to get social and industrial justice, we have suffered from the tyranny of a small minority. We have been denied, now by one court, now by another, as in the Bakeshop case, where the courts set aside the law limiting the hours of labor in bakeries—the “due process” clause again as in the Workmen’s Compensation Act, as in the Tenement House Cigar Factory case—in all these and many other cases we have been denied by small minorities, by a few worthy men of wrong political philosophy on the bench, the right to protect our people in their lives, their liberty, and their pursuit of happiness.[8] . . .

. . . When, as the result of years of education and debate, a majority of the people have decided upon a remedy for an evil from which they suffer, and have chosen a legislature and executive pledged to embody that remedy in law, and the law has been finally passed and approved, I regard it as monstrous that a bench of judges shall then say to the people: “You must begin all over again. First amend your Constitution [which will take four years]; second, secure the passage of a new law [which will take two years more]; third, carry that new law over the weary course of litigation [which will take no human being knows how long]; fourth, submit the whole matter over again to the very same judges who have rendered the decision to which you object. Then, if your patience holds out and you finally prevail, the will of the majority of the people may have its way.” Such a system is not popular government, but a mere mockery of popular government. It is a system framed to maintain and perpetuate social injustice, and it can be defended only by those who disbelieve in the people, who do not trust them, and, I am afraid I must add, who have no real and living sympathy with them as they struggle for better things. . . .

The decisions of which we complain are, as a rule, based upon the constitutional provision that no person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. The terms “life, liberty, and property” have been used in the constitutions of the English-speaking peoples since Magna Carta. Until within the last sixty years they were treated as having specific meanings; “property” meant tangible property; “liberty” meant freedom from personal restraint, or, in other words, from imprisonment in its largest definition. About 1870 our courts began to attach to these terms new meanings. Now “property” has come to mean every right of value which a person could enjoy, and “liberty” has been made to include the right to make contracts. As a result, when the state limits the hours for which women may labor, it is told by the courts that this law deprives them of their “liberty”; and when it restricts the manufacture of tobacco in a tenement, it is told that the law deprives the landlord of his “property.” Now, I do not believe that any people, and especially our free American people, will long consent that the term “liberty” shall be defined for them by a bench of judges. Every people has defined that term for itself in the course of its historic development. Of course, it is plain enough to see that, in a large way, the political history of man may be grouped about these three terms, “life, liberty, and property.” There is no act of government which cannot be brought within their definition, and if the courts are to cease to treat them as words having a limited, specific meaning, then our whole government is brought under the practically irresponsible supervision of judges. As against that kind of a government I insist that the people have the right, and can be trusted, to govern themselves. This our opponents deny; and the issue is sharply drawn between us. . . .

Friends, our task as Americans is to strive for social and industrial justice, achieved through the genuine rule of the people. This is our end, our purpose. The methods for achieving the end are merely expedients, to be finally accepted or rejected according as actual experience shows that they work well or ill. But in our hearts we must have this lofty purpose, and we must strive for it in all earnestness and sincerity, or our work will come to nothing. In order to succeed we need leaders of inspired idealism, leaders to whom are granted great visions, who dream greatly and strive to make their dreams come true; who can kindle the people with the fire from their own burning souls. The leader for the time being, whoever he may be, is but an instrument, to be used until broken and then to be cast aside; and if he is worth his salt he will care no more when he is broken than a soldier cares when he is sent where his life is forfeit in order that the victory may be won. In the long fight for righteousness the watchword for all of us is spend and be spent. It is of little matter whether any one man fails or succeeds; but the cause shall not fail, for it is the cause of mankind. We, here in America, hold in our hands the hope of the world, the fate of the coming years; and shame and disgrace will be ours if in our eyes the light of high resolve is dimmed, if we trail in the dust the golden hopes of men. If on this new continent we merely build another country of great but unjustly divided material prosperity, we shall have done nothing; and we shall do as little if we merely set the greed of envy against the greed of arrogance, and thereby destroy the material well-being of all of us. To turn this government either into government by a plutocracy or government by a mob would be to repeat on a larger scale the lamentable failures of the world that is dead. We stand against all tyranny, by the few or by the many. We stand for the rule of the many in the interest of all of us, for the rule of the many in a spirit of courage, of common sense, of high purpose, above all in a spirit of kindly justice toward every man and every woman. We not merely admit, but insist, that there must be self-control on the part of the people, that they must keenly perceive their own duties as well as the rights of others; but we also insist that the people can do nothing unless they not merely have, but exercise to the full, their own rights. The worth of our great experiment depends upon its being in good faith an experiment—the first that has ever been tried—in true democracy on the scale of a continent, on a scale as vast as that of the mightiest empires of the Old World. Surely this is a noble ideal, an ideal for which it is worthwhile to strive, an ideal for which at need it is worthwhile to sacrifice much; for our ideal is the rule of all the people in a spirit of friendliest brotherhood toward each and every one of the people.

- 1. The Republican Party National Convention was held in June 1912. For the first time, direct primaries played a key role in the nomination process. Although Theodore Roosevelt would ultimately win nine of the thirteen states that held Republican primaries, not all primary results were binding on delegates, and most states at the time did not hold primary elections. Two-thirds of the Republican National Convention delegates were chosen in meetings heavily influenced by state party leaders, most of whom backed William Howard Taft. At a contested national convention, Roosevelt claimed that party leadership representing wealthy special interests had stolen the nomination from him, and he broke from the party to run as a “Bull Moose” progressive.

- 2. Efforts at passing a direct primary law in New York had failed in 1909 and 1910, and the high-profile Roosevelt had publicly supported the reform. In October 1911 New York managed to approve a direct primary law, but not to the satisfaction of Roosevelt and many proponents of direct primaries. The 1911 law established a nonbinding primary in which voters could express their preference of candidates, but the New York Republican State Committee could petition the decision and nominate another candidate.

- 3. Progressive legal scholar and U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (1841–1935). On property and due process, see the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

- 4. The “police power” refers to the right of a government to secure the common good for its citizens within its own sovereign territory. See Holmes’ opinion in Noble State Bank v. Haskell, 219 U.S. 104 (1911). Here the U.S. Supreme Court upheld an Oklahoma law that required banks to provide a percentage of their average daily deposits toward a depositors’ guaranty fund. Holmes reasoned that the law satisfied the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process requirements and, under its general police power, the state legislature may pass such a law to foster the public good.

- 5. See Ives v. South Buffalo Railway Company, 201 N.Y. 271 (1911). Here the New York State Court of Appeals struck down a state law that required employers to compensate workers injured on the job. The court held that such legislation took property from employers without due process of law (unless it could be shown that worker injuries were the result of negligence on the part of the employer).

- 6. See Pacific States Telephone and Telegraph Company v. Oregon, 223 U.S. 118 (1912).

- 7. Taft routinely criticized the popular recall of judicial decisions as inconsistent with American constitutionalism and healthy majority rule. See, for example, his address in Toledo, Ohio, titled “The Judiciary and Progress” (March 8, 1912), and his address at the State House in Concord, New Hampshire (March 19, 1912).

- 8. See Matter of Application of Jacobs, 98 N.Y. 98 (1885); Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905); Ives v. South Buffalo Railway Company, 201 N.Y. 271 (1911).

Progressive Party Platform of 1912

August 07, 1912

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.