No related resources

Introduction

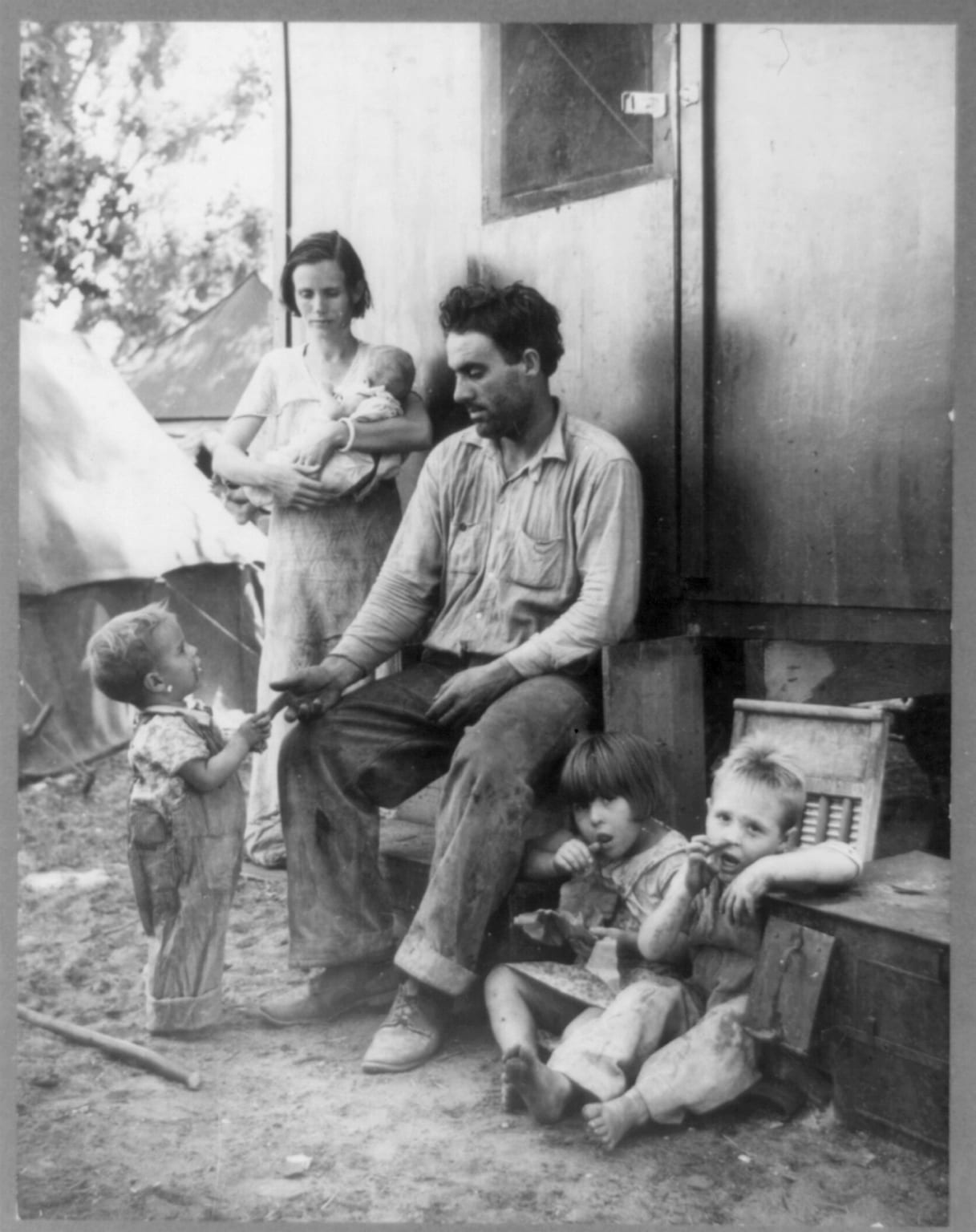

Not long after the decision in Myers v. United States, the Supreme Court had a separate occasion to decide another case on the removal power. Between Myers (1926) and Humphrey’s Executor (1935), the political situation had significantly changed. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal dramatically altered the balance of power between the legislature and the executive by shifting a significant amount of policymaking to the executive branch. In light of these changes, independent regulatory agencies (IRCs) such as the Federal Trade Commission took on new significance for Congress. Most of the IRCs consisted of a board of commissioners who were appointed by the president with the advice and consent of the Senate but could be removed only for “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.” In the case of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the commissioners served for various lengths of tenure and the board required a bipartisan composition of members.

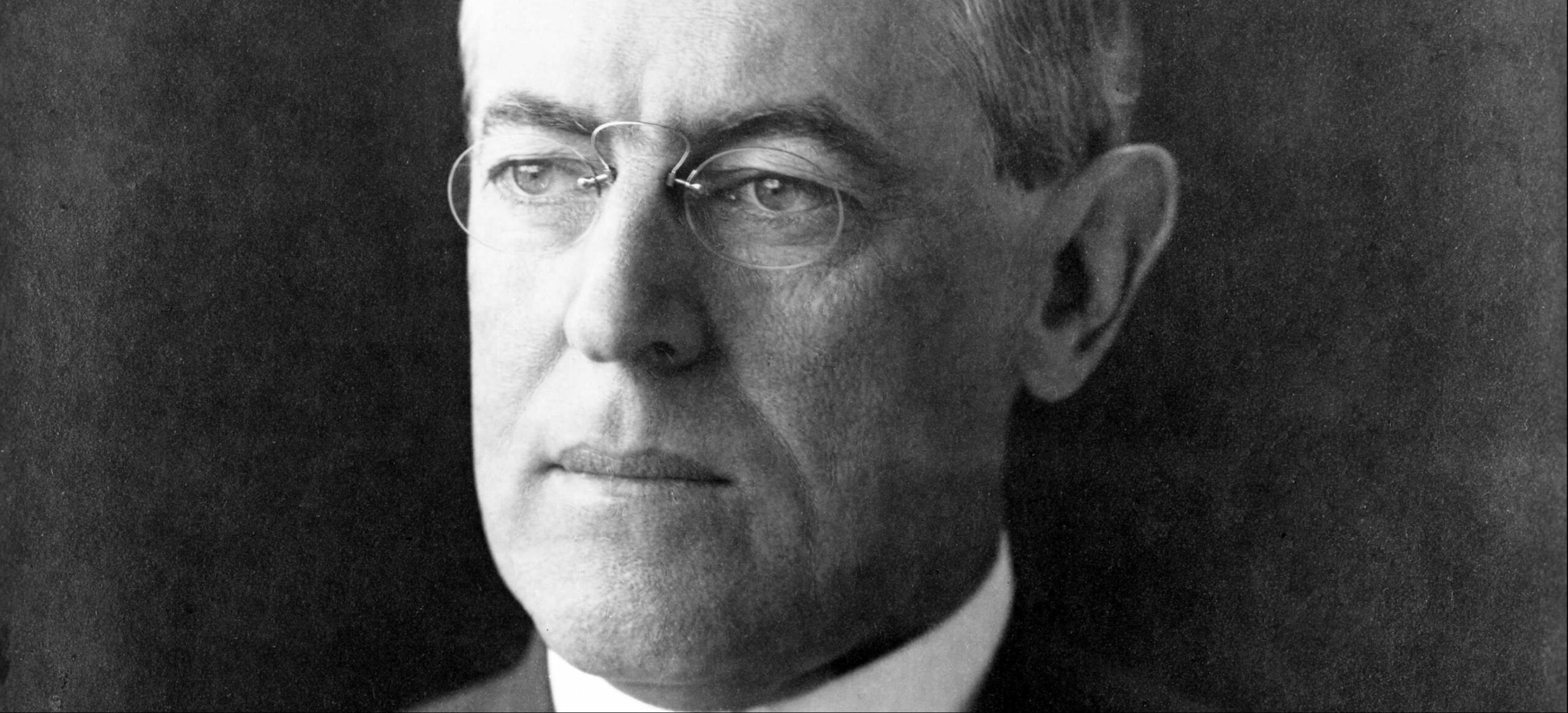

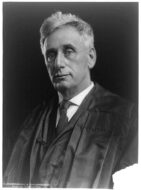

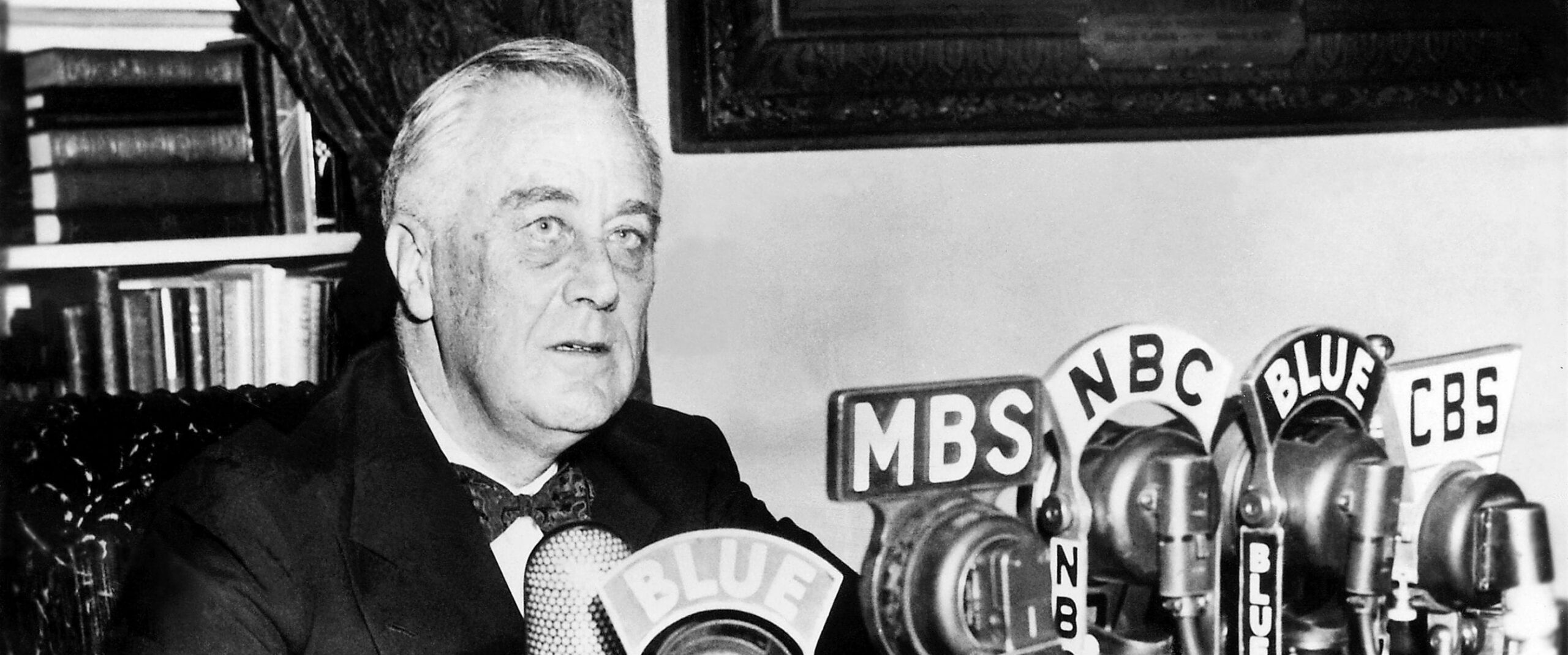

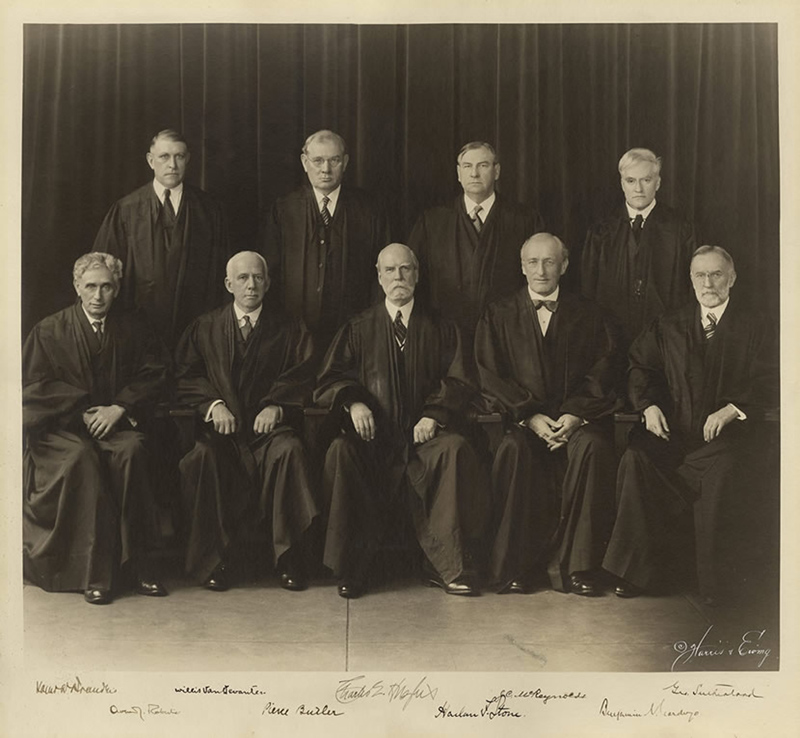

On August 31, 1933, FDR wrote to FTC commissioner William Humphrey (1862–1934), a Hoover appointee: “You will, I know, realize that I do not feel that your mind and my mind go along together on either the policies or the administering of the Federal Trade Commission, and, frankly, I think it is best for the people of this country that I should have a full confidence.” The commissioner declined to resign; and on October 7, 1933, the president wrote him: “Effective as of this date you are hereby removed from the office of Commissioner of the Federal Trade Commission.” Humphrey died the following year, but his executor brought a suit in federal court to recover his salary, arguing that his dismissal by the president violated the statute’s “ for cause” removal provisions. Justice George Sutherland (1862–1942), writing for a unanimous Court, ruled against the president and upheld the law’s limitations on executive removal, arguing that FTC commissioners are not executive officers but serve in a “quasi legislative” and “quasi judicial role.” The decision defined the legal grounds for numerous independent regulatory commissions in the future.

295 U.S. 602 (1935), https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/295/602/

Mr. Justice Sutherland delivered the opinion of the Court:

. . .The Federal Trade Commission Act creates a commission of five members to be appointed by the president by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, and section 1 provides: “Not more than three of the commissioners shall be members of the same political party. The first commissioners appointed shall continue in office for terms of three, four, five, six, and seven years, respectively, from the date of the taking effect of this act [September 26, 1914], the term of each to be designated by the president, but their successors shall be appointed for terms of seven years . . .”

. . .The commission is to be nonpartisan; and it must, from the very nature of its duties, act with entire impartiality. It is charged with the enforcement of no policy except the policy of the law. Its duties are neither political nor executive, but predominantly quasi judicial and quasi legislative. Like the Interstate Commerce Commission, its members are called upon to exercise the trained judgment of a body of experts “appointed by law and informed by experience.”. . .

. . .[T]he language of the act, the legislative reports, and the general purposes of the legislation as reflected by the debates, all combine to demonstrate the congressional intent to create a body of experts who shall gain experience by length of service; a body which shall be independent of executive authority, except in its selection, and free to exercise its judgment without the leave or hindrance of any other official or any department of the government. To the accomplishment of these purposes, it is clear that Congress was of opinion that length and certainty of tenure would vitally contribute. And to hold that, nevertheless, the members of the commission continue in office at the mere will of the president, might be to thwart, in large measure, the very ends which Congress sought to realize by definitely fixing the term of office.

We conclude that the intent of the act is to limit the executive power of removal to the causes enumerated, the existence of none of which is claimed here; and we pass to the second question.

. . .To support its contention that the removal provision of section 1, as we have just construed it, is an unconstitutional interference with the executive power of the president, the government’s chief reliance is Myers v. United States.1…

The office of a postmaster is so essentially unlike the office now involved that the decision in the Myers case cannot be accepted as controlling our decision here. A postmaster is an executive officer restricted to the performance of executive functions. He is charged with no duty at all related to either the legislative or judicial power. The actual decision in the Myers case finds support in the theory that such an officer is merely one of the units in the executive department and, hence, inherently subject to the exclusive and illimitable power of removal by the chief executive, whose subordinate and aid he is. . . .

The Federal Trade Commission is an administrative body created by Congress to carry into effect legislative policies embodied in the statute in accordance with the legislative standard therein prescribed, and to perform other specified duties as a legislative or as a judicial aid. Such a body cannot in any proper sense be characterized as an arm or an eye of the executive. Its duties are performed without executive leave and, in the contemplation of the statute, must be free from executive control. In administering the provisions of the statute in respect of “unfair methods of competition,” that is to say, in filling in and administering the details embodied by that general standard, the commission acts in part quasi legislatively and in part quasi judicially. In making investigations and reports thereon for the information of Congress under section 6, in aid of the legislative power, it acts as a legislative agency. Under section 7, which authorizes the commission to act as a master in chancery under rules prescribed by the court, it acts as an agency of the judiciary. To the extent that it exercises any executive function—as distinguished from executive power in the constitutional sense2—it does so in the discharge and effectuation of its quasi legislative or quasi judicial powers, or as an agency of the legislative or judicial departments of the government.3…

We think it plain under the Constitution that illimitable power of removal is not possessed by the president in respect of officers of the character of those just named. The authority of Congress, in creating quasi legislative or quasi judicial agencies, to require them to act in discharge of their duties independently of executive control cannot well be doubted; and that authority includes, as an appropriate incident, power to fix the period during which they shall continue, and to forbid their removal except for cause in the meantime. For it is quite evident that one who holds his office only during the pleasure of another cannot be depended upon to maintain an attitude of independence against the latter’s will.

The fundamental necessity of maintaining each of the three general departments of government entirely free from the control or coercive influence, direct or indirect, of either of the others, has often been stressed and is hardly open to serious question. So much is implied in the very fact of the separation of the powers of these departments by the Constitution; and in the rule which recognizes their essential coequality. The sound application of a principle that makes one master in his own house precludes him from imposing his control in the house of another who is master there. . . .

The power of removal here claimed for the president falls within this principle, since its coercive influence threatens the independence of a commission which is not only wholly disconnected from the executive department, but which, as already fully appears, was created by Congress as a means of carrying into operation legislative and judicial powers, and as an agency of the legislative and judicial departments.

In the light of the question now under consideration, we have reexamined the precedents referred to in the Myers case, and find nothing in them to justify a conclusion contrary to that which we have reached. The so-called “Decision of 1789”4 had relation to a bill proposed by Mr. Madison to establish an executive Department of Foreign Affairs. . . .A reading of the debates shows that the president’s illimitable power of removal was not considered in respect of other than executive officers. And it is pertinent to observe that when, at a later time, the tenure of office for the comptroller of the Treasury was under consideration, Mr. Madison quite evidently thought that, since the duties of that office were not purely of an executive nature but partook of the judiciary quality as well, a different rule in respect of executive removal might well apply.

The result of what we now have said is this: Whether the power of the president to remove an officer shall prevail over the authority of Congress to condition the power by fixing a definite term and precluding a removal except for cause will depend upon the character of the office; the Myers decision, affirming the power of the president alone to make the removal, is confined to purely executive officers; and as to officers of the kind here under consideration, we hold that no removal can be made during the prescribed term for which the officer is appointed, except for one or more of the causes named in the applicable statute. . . .

- 1. See Myers v. United States

- 2. Sutherland seemed to be making a distinction between the power of the president to enforce the law (“executive power in the constitutional sense”) and mere administrative duties that are assigned to an agency by statutory law. In administering the law, these regulatory commissions are not executive in the sense that they are enforcing a law, but rather they wield administrative powers to hear cases and create rules for fair trade.

- 3. Justice Sutherland’s note: The provision of section 6(d) of the act (15 USCA § 46(d)) that authorizes the president to direct an investigation and report by the commission in relation to alleged violations of the antitrust acts is so obviously collateral to the main design of the act as not to detract from the force of this general statement as to the character of that body.

- 4. The “Decision of 1789” was the debate in Congress in 1789 over whether Article II of the Constitution granted the president the power to remove officers of the executive branch at will.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.