No related resources

Introduction

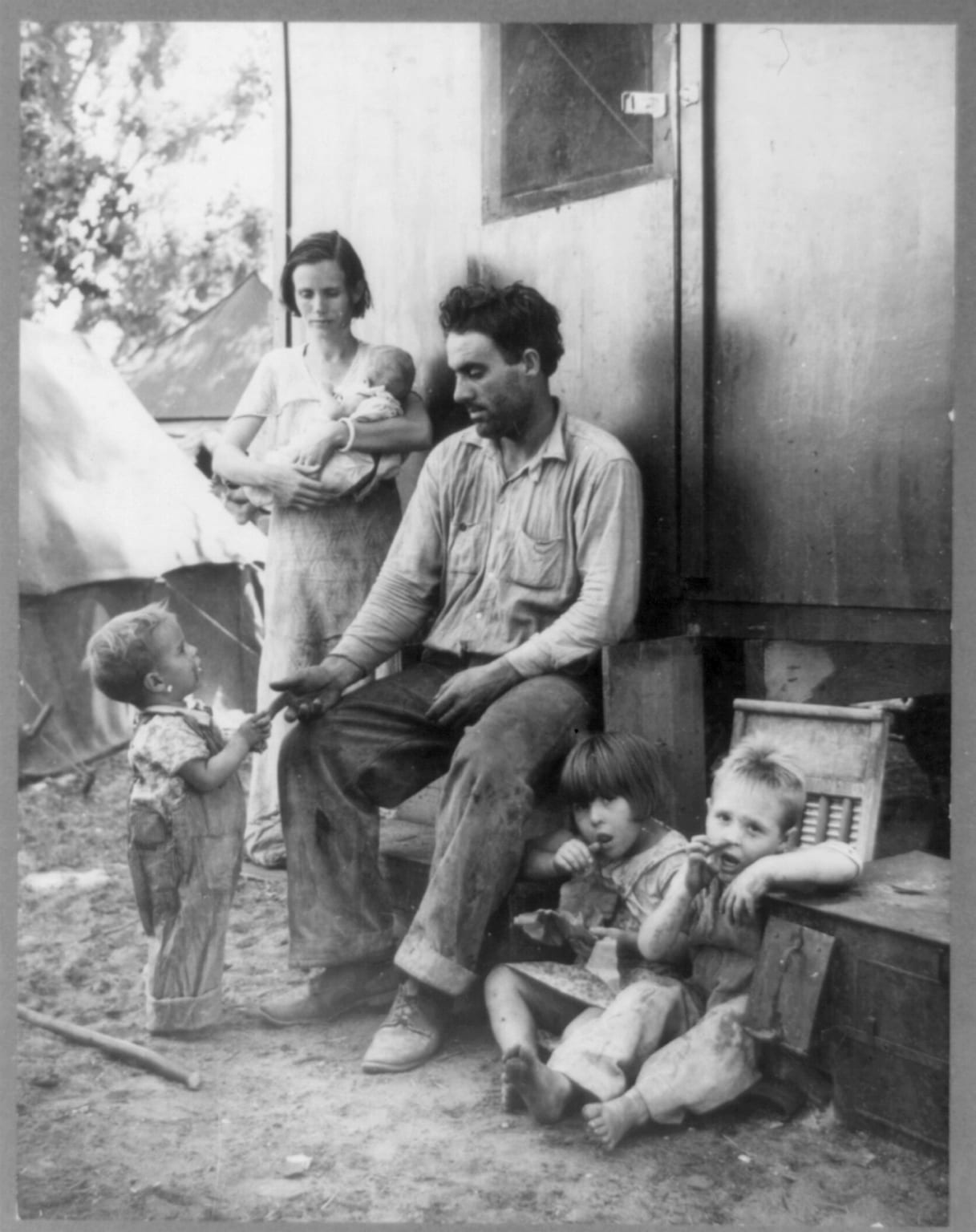

Adding to the economic distress of the 1930s was a serious drought that affected certain parts of the Great Plans for as long as eight years. Decades of over-plowing, which destroyed the root systems that kept topsoil in place, combined with the dry conditions to produce an environmental disaster known as the “Dust Bowl.” In 1934, and again in 1936, high winds simply blew precious soil into the sky, creating gigantic dust clouds that spread as far as New York City and Washington, DC. Oklahoma and the Texas panhandle were the hardest hit, but parts of Arkansas, New Mexico, Colorado, Iowa, Nebraska, and Kansas were affected as well. As many as 3.5 million farmers in this region, having watched as their land became effectively barren, packed up their belongings and headed to California in one of the largest migrations in U.S. history. Their arrival was noted by economist Paul Taylor, who chronicled their plight in the pages of the magazine Survey Graphic.

Source: Survey Graphic 24:7 (July 1935), p. 348.

Vast clouds of dust rise and roll across the Great Plains, obscuring the lives of people, blighting homes, hampering traffic, drifting eastward to New York and westward to California. They carry the natural riches of the plains and deposit them broadcast over the nation. Exposed by cultivation which killed the protecting grasses, and powdered by protracted drought, the rich topsoil is being stripped from tens of thousands of acres by wind erosion, leaving land and life impoverished.

Dust, drought, and protracted depression have exposed also the human resources of the plains to the bleak winds of adversity. After the drifting dust clouds drift the people; over the concrete ribbons of highway which lead out in every direction come the refugees. We are witnessing the process of social erosion and a consequent shifting of human sands in a movement which is increasing and may become great.

At Fort Yuma the bridge over the Colorado marks the southeastern portal to California. Across this bridge move shiny cars of tourists, huge trucks, an occasional horse and wagon, or a Yuma Indian on horseback. And at intervals in the other traffic appear slow-moving and conspicuous cars loaded with refugees.

The refugees travel in old automobiles and light trucks, some of them homemade, and frequently with trailers behind. All their worldly possessions are piled on the car and covered with old canvas or ragged bedding, with perhaps bedsprings atop, a small iron cook-stove on the running board, a battered trunk, lantern, and galvanized iron washtub tied on behind. Children, aunts, grandmothers and a dog are jammed into the car, stretching its capacity incredibly. A neighbor boy sprawls on top of the loaded trailer.

Most of the refugees are in obvious distress. Clothing is sometimes neat and in good condition, particularly if the emigrants left last fall, came via Arizona, and made a little money in the cotton harvest there. But sometimes it is literally in tatters. At worst, these people lack money even for a California auto license. Asked for the $3 fee, a mother with six children and only $3.40 replied, “That’s food for my babies!” She was allowed to proceed without a license.

White Americans of old stock predominate among the emigrants. Long, lanky Oklahomans with small heads, blue eyes, an Abe Lincoln cut to the thighs, and surrounded by tow-headed children; bronzed Texans with a drawl, clear-cut features, and an aggressive spirit; a few Mexicans, mestizos with many children; occasionally Negroes; all are crossing over into California.

The westward movement of rural folk from Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas and adjacent states, whence most of the refugees to California are now coming, of course is not new. The rise of cotton production in Imperial Valley1 in 1910 started migration of cotton pickers and growers from the Southwest. The spread of cotton culture to the San Joaquin Valley2 in 1919 accelerated the interstate movement; many came seasonally to harvest the cotton and returned, while others remained as a permanent accretion. The present migration, therefore, follows channels cut historically. But it moves, with the tremendous added impulses of drought and depression behind it, which increase its westward volume, and which may be expected to reduce the usual backflow.

The immediate factors dislodging people are several. Clearly, although piecemeal and in some bewilderment, the emigrants tell the story: “We got blowed out in Oklahoma.” – “Yes sir, born and raised in the state of Texas; farmed all my natural life. Ain’t nothin’ there to stay for – nothin’ to eat. Somethin’s radical wrong,” said an ex-cotton farmer encamped shelterless under eucalyptus trees in Imperial Valley. A mother with seven children whose husband died in Arizona en route explained: “The drought come and burned it up. We’d have gone back to Oklahoma from Arizona, but there wasn’t anything to go to.” – “Lots left ahead of us – no work of no kind.” – “It seems like God has forsaken us back there in Arkansas.”

Curiously, not only drought and depression but also flood and the very measures which mitigate the severity of depression for some people have unloosed others. A large party of Negroes from Mississippi entering California at Fort Yuma in March reported that they had “just beat the water out by a quarter of a mile.” A destitute share-crop farmer, stopping tentless by the highway near Bakersfield, with only green onions as food for his wife and children, had striven to buy a farm in Oklahoma and lost it. But he announced proudly that he had left Wagner County “clear,” owing no one. In his story were echoes of crop-restriction, naturally only of its sadder side, and of conflict between cotton share-croppers on one hand and “first tenants” and landlords on the other. “It knocks thousands of fellows like me out of a crop. The ground is laying there, growing up in weeds. The landowner got the benefit and the first tenant [who finances the crop and provides teams and tools, feed and seed] says ‘I can’t furnish [subsistence during the growing season] any more,’ so the share-crop tenant ‘on halves’ goes on FERA;3 he’s out. It’s putting ’em down, down, down. It looks to me like overproduction is better than not having it.” Another refugee who had been farm laborer and oil worker in Oklahoma, said, “Since the oil-quota, I’ve had no work.”4

It is hope that draws the refugees to California, hope of finding work, of keeping off or getting off federal relief, of maintaining morale, of finding surcease of trouble. “We haven’t had to have no help yet. Lots of ’em have, but we haven’t,” said Oklahoma pea-pickers on El Camino Real at Mission San Jose. “All I want is a chance to make an honest living.” – “When a person’s able to work, what’s the use of begging? We ain’t that kind of people,” said elderly pea-pickers near Calipatria.5

To some few migrants without responsibility, there is hardly more in it all than adventure. A group of young hillbillies, living in a brush hut evacuated by Filipinos, can take a day off from the carrot fields of Imperial Valley, lie about barefoot at a game of cards, and blithely play Home Sweet Home on a harmonica.

Of course, many refugees do not shun relief. A California border official reports that refugees say, “People are better cared for here than in the cotton states,” correctly implying one motive for emigration. Yet many who do not receive relief and are desperately in need of it for themselves and their children, avoid seeking it as long as possible. Many who would leave cannot, for lack of resources. These, like the tenants who write hopefully from Oklahoma that “If we can make a crop this year, we’ll come to California,” await only a good harvest to emigrate.

But there is agony in tearing up roots, even when these have been loosened by adversity. “God only knows why we left Texas, ’cept he’s in a movin’ mood,” said a wife who accepted reluctantly the decision of her husband to leave.

Many families comfort themselves with the thought of return home when drought and depression are over. Many will return, but many others will not; they have burned their bridges without realizing it. Now the movement is west. A pregnant Oklahoma mother living without shelter in Imperial Valley while the menfolk bunched carrots for money to enable them to move on, made poignant request for directions. “Where is Tranquility, California?” To most of the refugees hope is greater than obstacles. With bedding drenched by rain while he slept in the open, with topless car and a tire gone flat, an Oklahoman with the usual numerous dependents could say, “Pretty hard on us now. Sun’ll come out pretty soon and we’ll be all right.”

Unfortunately “tranquility” is not generally reached by those seeking refuge on the coast. Land is not readily available for new farmers nor is the local reception altogether friendly. Oregonians are already becoming concerned over the influx of settlers in their midst. California agricultural workers are restive at the increase of competitors. And the legislature of that state is presented with a bill to exclude all “indigent persons or persons liable to become public charges,” and to deport all who enter in violation of the prohibition. In the spirit of the legislature which sought unconstitutionally to debar Chinese immigrants from California in the 50’s, the present session is asked to exclude American “immigrants” without money.6 “The state,” said one of the sponsors of the bill, “has the power to protect itself from economic disaster. This is the justification. . . . It transcends legalistic argument.” In the Los Angeles Times “the Lancer” cries in alarm: “That 5000 indigents are coming into Southern California. . . leaves one appalled. This is the gravest problem before the United States. . . these tattered migrations.” Lamenting good roads he adds: “The Chinese, wiser than we, have delayed building a great system of highways for that very reason – to head off these dangerous migrations – indigent people stampeding from the farms into cities to live on charity. Incidentally, that was one of the reasons why Rome crashed.”

The drought emigrants, however, have moved into rural California rather than to the cities. For in agriculture the labor market is highly fluid, and almost anyone is free to try his hand when work is to be done; although skill is essential to good earnings, anyone can get the opportunity to bunch some carrots. So they gravitate naturally into a labor population which moves incessantly from harvest to harvest, which lives in poverty under generally unsanitary and inadequate conditions and which competes for work in a market so glutted that even the farmers cry for protection because strikes are readily kindled when great underemployed “surpluses” collect.

Thus the refugees seeking individual protection in the traditional spirit of the American frontier by westward migration are unknowingly arrivals at another frontier, one of social conflict. In this conflict they are found on both sides. An ex-tenant farmer picking peas in Imperial Valley complains there of the great landowners who are also the bane of his class in Oklahoma whence he came, “The monied men got all the land gobbled up.” In the sheds of El Centro the lettuce packers were on strike this spring. A family of refugees in dire distress naturally helped to break strike. With the earnings, they purchased an automobile needed badly for family support. They had learned what other laborers learn quickly in the highly seasonal agriculture of the coast, “A person can’t get by without a car in California, like in Oklahoma.”

Participation in more labor conflict doubtless lies ahead of the refugees coming to California, for tension in that state is not abating. The bitter criminal syndicalist trials in Sacramento7 were hailed by extremists as a test of power; half the defendants were acquitted, half were convicted. Among the latter were the chief leaders of the agricultural strikes of 1933. Farmers and their spokesmen have exhibited great confidence in repression of agitators and pickets as a means of maintaining peace in agriculture. But still they are uneasy as the successive harvests of 1935 advance. Expending as much as $35 or $50 an acre to bring a crop to maturity, they see their entire year’s return staked upon a few days of uninterrupted harvest. The fifty-odd farm strikes since December 1932 naturally have made them fearful of more interruptions, and they have organized for self-defense. “The Associated Farmers,”8 said their spokesman before the Commonwealth Club, “intend to get laws passed that will protect them against Communists, and to see that these laws are rigidly enforced. We are not trying to beat down wages; we are not advocating illegal force or terrorism. But we will not willingly submit to having twenty or thirty automobile loads of so-called peaceful picketers parading up and down in front of our homes, threatening and intimidating, and even blockading the highways.” Unions under conservative labels are almost equally opposed. “If the American Federation of Labor9 should form farm unions, the chances are that foreign or native-born radicals would sooner or later get control of them, just as they did with the longshoremen’s union.” Commenting on this attitude a State Federation official said bitterly, “If we had a strike, the farmers would conveniently find one or two Communists around.”

The future of the refugees, then, is hardly likely to be tranquil. They will be caught in whatever rural labor struggles arise. Like their predecessors of recent years some will find a degree of economic and physical stability in California, but others will mill incessantly through the harvests and live in squatters’ camps and rural slums, unless a protecting government intervenes. The refugees are conscious of their present destitution and enforced mobility, and grope for help: “Poor folks has poor ways, you know.” – “There’s more or less humiliation living this way, but we can’t help it. Our tent’s wore out.” – “Can’t we have better houses?” – “What bothers us travellin’ people most is we can’t get no place to stay still.” But the struggle against unsanitary conditions, flies, and bad water is too much for many people and they give up. “I hate to boil the water, because then it has so much scum on it,” said a pea-picker who drew his water from the irrigating ditch in the usual manner.

The refugees discuss the Townsend plan.10 They sense demoralization and the futility of continual relief: “This giving people something don’t do no good.” – “This relief business is all a fake anyway. When they get on it they don’t want to work any more.” Grasping the idea of rehabilitation, a refugee recipient of relief said, “If they’d a’ give it to me in one chunk I could a’ gone back and bought me a little piece o’ land.” But the problem is bewildering to most of them. “We was out here nine years ago; then we could get a steady job. Now it seems we can’t stay in one place. We got to follow these little jobs to live.” – “I’m not smart enough to know what ought to be done; it sure doesn’t suit me.”

Across the border at Fort Yuma the refugees are straggling west. They are not newly shod and clad, moved under government direction by train and a trim army transport, nor met by mayors and brass bands, like the drought sufferers from Minnesota bound for the colonization of Alaska.11 But they constitute already a far greater, if unplanned and almost unnoticed redistribution of the nation’s population. To the Alaskan colonists the Matanuska Valley “looks like Heaven.” To an Oklahoman who crossed the Tehachapi and viewed the wild flowers of the southern San Joaquin Valley, California “looks like Paradise compared to what it was there.”

But questions of the future, both immediate and remote, arise. Will California continue to look like Paradise as the harvests wear on, and the refugees realize that they are definitely a part of the under-employed labor army – white Americans, Mexicans, Negroes, and Filipinos – mobile and restless, which has engaged in strike after strike? Is it conceivable that the grandchildren of the emigrants of 1935 will take pride in placing grandmother’s cook-stove and trunk in museums beside the gold-seeker’s pan or the table which came ’round the Horn in ’51?12 Or will these children of distress who creep west unheralded have no share in California history and tradition? The lure of gold in the past, and of land, has been superseded by the expelling forces of drought and depression in the present.

What of the future, when mechanical cotton pickers invade the Old South, making human hands unnecessary? What of the Southern tenants and laborers under the ominous cloud of invention? What will they do? Where will they go? Are the refugees of today the last Western emigrants, or are they but forerunners of greater migrations of hope and despair to come?

- 1. Imperial Valley is in southeastern California.

- 2. The San Joaquin Valley comprises the southern half of the Central Valley of California and is the most intensively cultivated region in the state.

- 3. Federal Emergency Relief Administration

- 4. This paragraph refers to several New Deal programs, intended to boost agricultural product prices by controlling economic activity, that the refugees believed made their situation more difficult. See the introduction to Document 25.

- 5. Calipatria is a city in Imperial County, California.

- 6. Concern about Chinese immigration rose in California in the 1850s, as Chinese immigrants competed for jobs. The state legislature passed legislation in the 1850s intended to limit this competition and discourage Chinese immigrants. It is unclear why the author referred to these laws as unconstitutional. He may have had in mind the 14th amendment, not ratified until 1868, or federal laws, or Supreme Court decisions which also came about after the 1850s.

- 7. Eighteen labor leaders were tried in Sacramento for “criminal syndicalism,” advocating the overthrow of the U.S. government.

- 8. The Associated Farmers was an organization of farm owners and their supporters in the 1930s who sought to counter efforts to organize farm workers.

- 9. The American Federation of Labor, as its name suggests, was a federation of unions, the largest such organization in the United States in the first half of the 20th century.

- 10. Proposed by Francis Townsend in 1933, the Townsend plan was a pension plan for the retired over 60 to be funded by a 2% national sales tax. It was a forerunner of social security. See Documents 23 and 26.

- 11. As part of its efforts to deal with the economic crisis, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration set up several colonies to which distressed people could move. One of these was in Alaska, to which 203 families from the upper mid-west moved.

- 12. Some of those traveling to California during the 1850s gold rush came by boat, around the tip of South America, Cape Horn.

Criticism of the Neutrality Act of 1935

August 24, 1935

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.