No related resources

Introduction

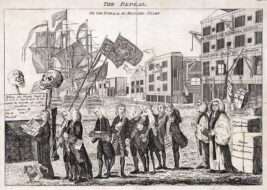

Although Parliament in 1770 repealed most of the taxes associated with the Townshend Acts, the duty on tea remained. Colonists continued their boycott of the product, and by 1773 nearly 10,000 tons of tea sat in the East India Company’s London warehouses. Parliament’s passage of the Tea Act aimed to rescue the near-bankrupt company, which had many well-connected shareholders and owed money to both the Bank of England and the British government. The act awarded the company a monopoly on the legal sale of tea in America and eliminated the duty the company paid to land tea in England. The tax to be paid by colonists who imported tea from England remained, but the law would tempt them to violate their boycott by making East India Company tea less expensive than Dutch tea smuggled into the colonies.

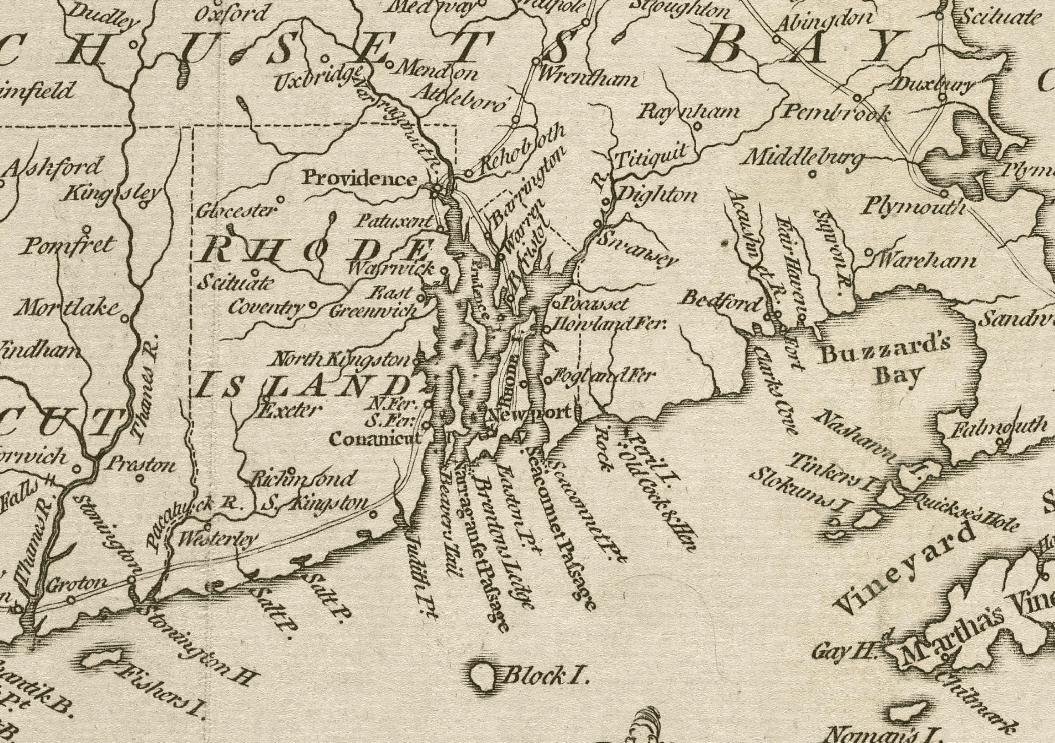

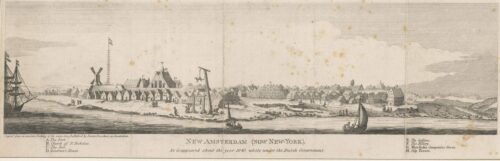

As in Philadelphia, New York, and other American ports, Bostonians viewed the Tea Act as a challenge to their virtue and a trick to cause them to accept taxation without representation. As a result, the November 28 arrival of the Dartmouth and its shipment of tea triggered a crisis. The Sons of Liberty stationed guards at Griffin’s Wharf to prevent the unloading of the Dartmouth’s cargo. Yet Governor Thomas Hutchinson, who had at his disposal British troops as well as British warships, refused to allow the Dartmouth to leave. By law the vessel had twenty days—until December 17—to pay the duty, after which the tea could be seized and then dispersed to sellers who might not know or care about its origins. The subsequent arrival of two additional ships carrying tea—the Eleanor and the Beaver—compounded the situation.

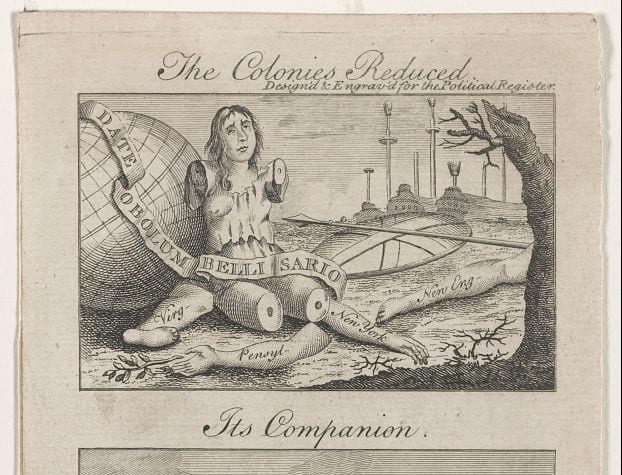

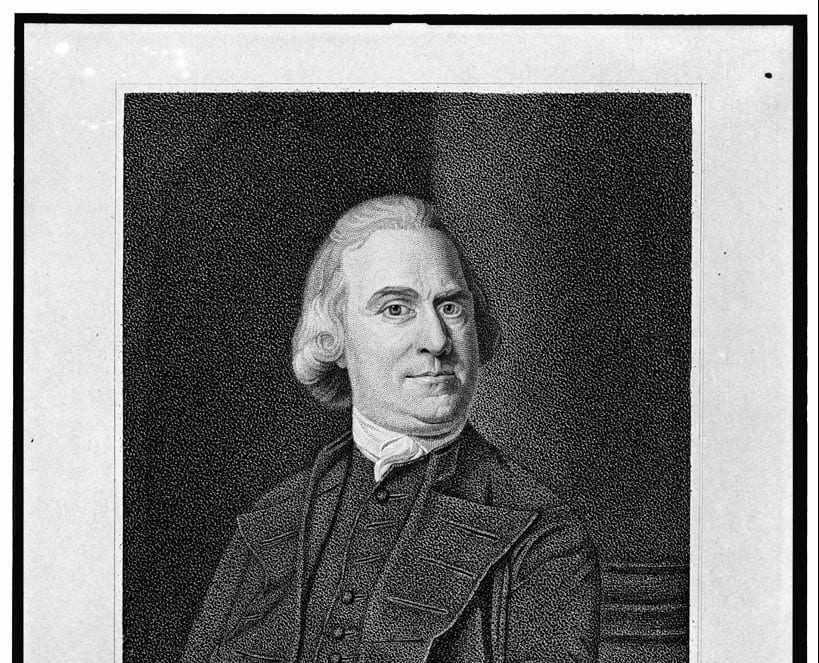

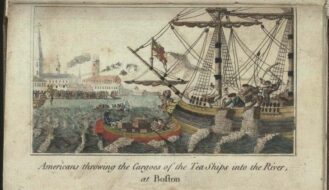

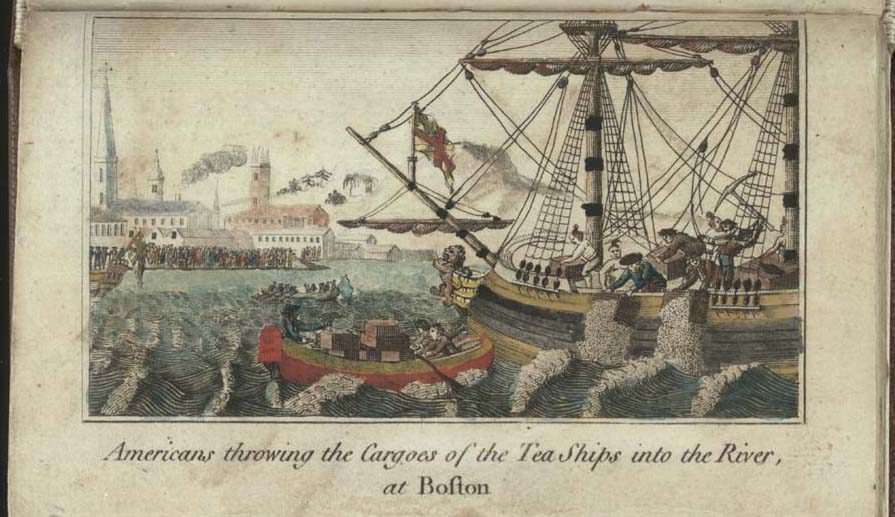

The account of “An Impartial Observer” described for newspaper readers how Bostonians, through a series of massive public meetings and then the concerted efforts of about fifty local men disguised as “Aboriginal Natives” (Mohawks, as others specified), confronted the crisis. Orchestrated by Sam Adams and the Sons of Liberty, the December 16 Tea Party destroyed 90,000 pounds of tea worth nearly £10,000. The following day, John Adams praised it in his diary as an act “so bold, so daring, so firm” that “it must have … important consequences.” It did. Parliament, which had repealed the Stamp Act and Townshend Acts in response to colonial protests, this time doubled down. Rather than attempting to prosecute individuals for the destruction of the tea, in early 1774 the British government punished all of Massachusetts with the Coercive Acts (Americans called them the “Intolerable Acts”), which closed Boston Harbor, hobbled the legislature, banned most town meetings, curtailed jury trials, expanded the quartering of British troops, and put America and Great Britain on a path toward war.

Source: “An Impartial Observer,” Boston Gazette, December 20, 1773.

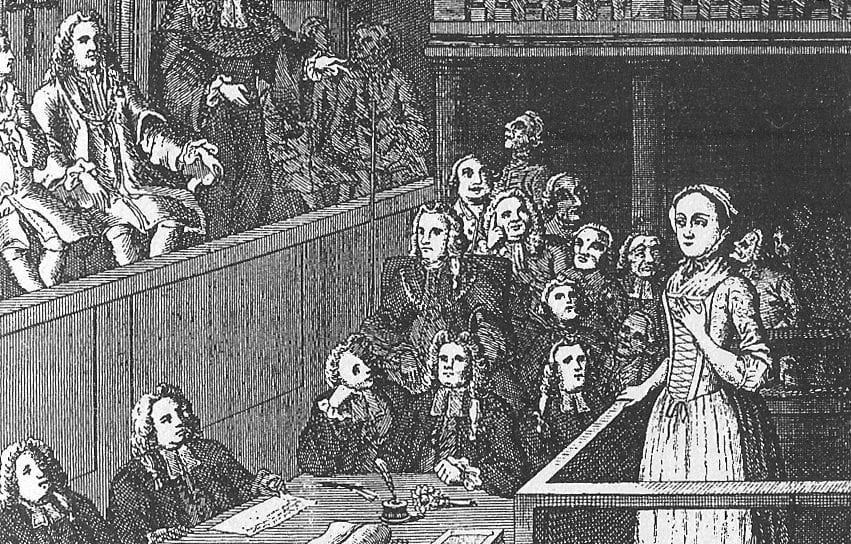

Having accidentally arrived at Boston upon a visit to a friend the evening before the meeting of the body of the people on the 29th of November, curiosity, and the pressing invitations of my most kind host, induced me to attend the meeting.

I must confess that I was most agreeably, and I hope that I shall be forgiven by the people if I say so, unexpectedly, entertained and instructed by the regular, reasonable, and sensible conduct and expression of the people there collected, that I should rather have entertained an idea of being transported to the British senate[1] than to an adventurous and promiscuous assembly of people of a remote colony, were I not convinced by the genuine and uncorrupted integrity and manly hardihood of the rhetoricians of that assembly that they were not yet corrupted by venality or debauched by luxury….

The body of the people determined the tea should not be landed. The determination was deliberate, was judicious; the sacrifice of their rights, of the union of all the colonies, would have been the effect had they conducted [themselves] with less resolution. On the committee of correspondence they devolved the care of seeing their resolutions reasonably executed. That body, as I had been informed by one of their members, had taken every step which prudence and patriotism could suggest, to effect the desirable purpose, but were defeated.

The body once more assembled [on December 14], I was again present. Such a collection of the people was to me a novelty; near seven thousand persons[2] from several towns, gentlemen, merchants, yeomen, and others, respectable for their rank and abilities, and venerable for their age and character, constituted the assembly. They decently, unanimously, and firmly adhered to their former resolution, that the baleful commodity which was to rivet and establish the duty should never be landed.

To prevent the mischief, they repeated the desires of the committee of the towns, that the owner of the ship should apply for a clearance; it appeared that Mr. Rotch[3] had been managed and was still under the influence of the opposite party; he resisted the request of the people to apply for a clearance for his ship with an obstinacy which, in my opinion, bordered on stubbornness. Subdued at length by the peremptory demand of the body, he consented to apply, a committee of ten respectable gentlemen were appointed to attend him to the collector.

The succeeding morning the application was made and the clearance refused with all the insolence of office; the body meeting the same morning by adjournment, Mr. Rotch was directed to protest in form, and then apply to the governor for a pass…. Mr. Rotch executed his commission with fidelity, but a pass could not be obtained, his excellency excusing himself in his refusal that he should not make the precedent of granting a pass till the clearance was obtained, which was indeed a fallacy as it had been usual with him in ordinary cases.

Mr. Rotch, returning in the evening [of December 16], reported as above; the body then voted his conduct to be satisfactory, and recommending order and regularity to the people, dissolved.

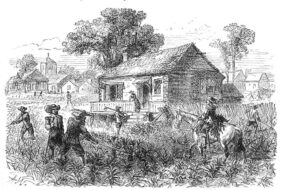

Previous to the dissolution, a number of persons, supposed to be the Aboriginal Natives from their complexion, approaching near the door of the assembly, gave the war whoop, which was answered by a few in the galleries of the house where the assembly was convened; silence was commanded, and a prudent and peaceable deportment again enjoined.

The savages repaired to the ships which entertained the pestilential teas, and had began their ravage previous to the dissolution of the meeting—they applied themselves to the destruction of this commodity in earnest, and in the space of about two hours broke up 342 chests, and discharged their contents into the sea.

A watch, as I am informed, was stationed to prevent embezzlement and not a single ounce of teas was suffered to be purloined or carried off. It is worthy [of] remark that, although a considerable quantity of goods of different kinds were still remaining on board the vessels, no injury was sustained; such attention to private property was observed, that a small padlock belonging to the capt[ain] of one of the ships being broke, another was procured and sent to him.

I cannot but express my admiration of the conduct of this people! Uninfluenced by party or any other attachment, I presume I shall not be suspected of misrepresentation.

The East India Company must console themselves with this reflection, that if they have suffered, the prejudice they sustain does not arise from enmity to them; a fatal necessity has rendered this catastrophe inevitable.

The landing the tea would have been fatal, as it would have saddled the colonies with a duty imposed without their consent, and which no power on earth can affect. Their strength, numbers, spirit, and illumination render the experiment dangerous, the defeat certain.

The consignees must attribute to themselves the loss of the property of the East India Company. Had they reasonably quieted the minds of the people by a resignation, all [would have]… been well. The customhouse, and the man who disgraces [his] majesty by representing him, acting in confederacy with the inveterate enemies of America, stupidly opposed every measure concerted to return the tea.

That American virtue may defeat every attempt to enslave them, is the warmest wish of my heart….

AN IMPARTIAL OBSERVER.

- 1. The House of Lords.

- 2. The Old South Meeting House was the largest building in Boston. Given its size, attendance was probably not more than 5,000—still an impressive number given that Boston had about 16,000 residents and nearby towns had only a few thousand more.

- 3. Francis Rotch (1750–1822), whose family owned the Dartmouth.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.