PROVERBS XXIX. 2.When the righteous are in authority, the people rejoice: but when the wicked beareth rule, the people mourn.

This is the observation of a wise ruler, relative to civil government; and the different effects of administration, according as it is placed in good or bad hands- and it having been preserved in the sacred oracles, not without providential direction, equally for the advantage of succeeding rulers, and other men of every class in society; it will not be thought improper by any, who have a veneration for revelation, and the instruction of princes, to make it the subject of our present consideration- Especially as our civil rulers, in acknowledgment of a superintending Providence, have invited us into the temple this morning, to ask counsel of God in respect to the great affairs of this anniversary, and the general conduct of government.

Accordingly, I shall take occasion from it- to make a few general remarks on the nature and end of civil government- point out some of the qualifications of rulers- and then apply the subject to the design of our assembling at this time.

First, I shall make a few remarks on the nature and end of civil government.

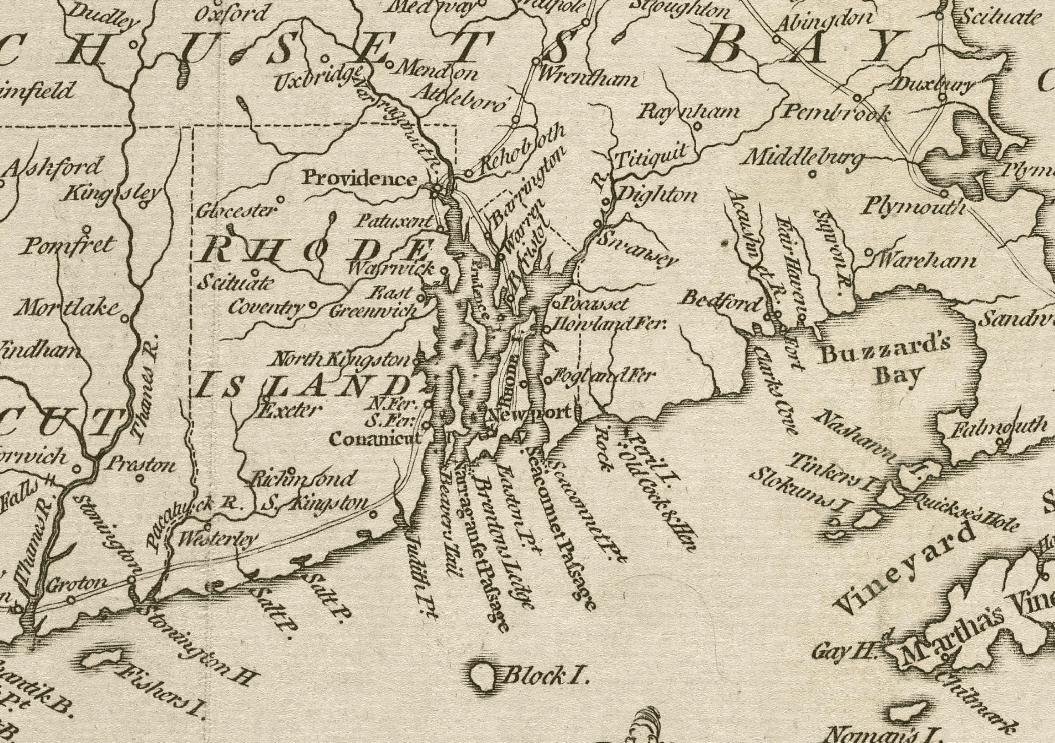

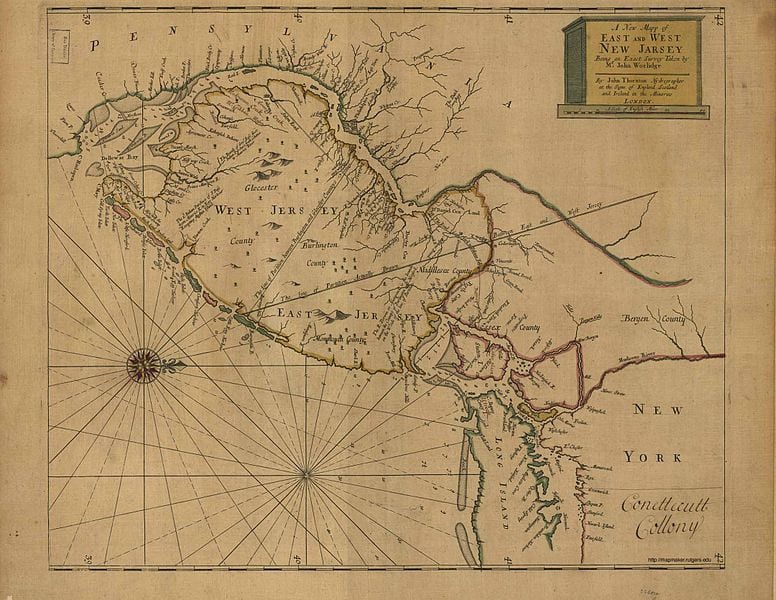

The people mentioned are a body politic- but whether the speaker had the Jewish state more especially in view; or, as is most probable, any civil society or kingdom on earth, is a point we need not precisely determine.- On either supposition, civil government is represented as being already established among them- rulers framed, and consented to, for the conduct of it- proper officers appointed, and vested with authority, on this constitutional basis, to make and execute such laws, in future, as should be found necessary; the public security and welfare being their grand object.- This, at least, appears to be the most just and rational idea of government that is founded in compact; as, I suppose, all governments, notwithstanding later usurpations, originally were; and if the compact, in early ages, hath not always been expressed; yet it has been necessarily implied, and understood, both by governors, and the governed, on their entering into society.

To this rise of government, the Hebrew polity, so far as it related only to civil matters, is not to be considered as an exception.- For although God, a most perfect Governor, for wise reasons, and as a distinguished favor, condescended to become the political head of the Jewish state; yet he did not think proper to exercise his absolute right of government over them, without the consent of the people.

And when they had foolishly and wickedly determined to give up this form of government, which was so wisely calculated for the public advantage, and substitute another in its room; their alwise and beneficent Governor did not see fit to exert his omnipotence to prevent it: Nor did he, as he justly might, abandon them for their impiety and ingratitude.

But analogous to the methods of his moral government, he went into a mode of conduct with them, adapted to their rational nature.- He treated them as free agents.- He solemnly protested against the change they were about to make in government; and, in order to disswade them from the rash attempt, he shewed them the manner of the king which should reign over them. But such paternal remonstrances proving ineffectual, and the people still persisting in their design, He not only permitted them to pursue it, but actually afforded them special aid and direction in the choice of their new king- that they might have one who should save them from their enemies- because their cry had come unto him.

This instance of the uneasiness of the nation of the Jews, under the most perfect form of government, may, perhaps, be alledged by some, as an argument of the utter incapacity of a people to judge of the rectitude of administration, or of their unreasonable peevishness and discontent, when they are governed well. It ought, however, to be considered, that though God was pleased to put himself at the head of the Jewish polity, yet officers, or rulers taken from among men, were appointed to act under Him, and these might not, and in fact did not always keep the great end of their investitute in view.

This was remarkably the case in the instance before us.- The sons of Samuel, who had been appointed judges over Israel, walked not in his ways, but turned aside after lucre, and took bribes, and perverted judgment; and the evil effects of their venality, and consequent perversion of public justice being known, and felt by the people, were the immediate occasion of their general uneasiness and complaint.

In this situation of their affairs, the way, indeed, was open before them. It was their indispensable duty, instead of withdrawing their allegiance, to have made their application to God their king, in a way of humble ardent prayer, for a redress of such enormities; and undoubtedly, He would have heard their petition, and returned an answer of peace, as He had before, in times of other dangers and distresses, often done.- Their sin and folly consisted in this neglect, and not in groundless suspicions, and unnecessary complaints: they had manifest cause of uneasiness- they were greatly injured, and oppressed by some of their executive officers: Bribery, which ought to be the abhorrence of all ranks, had corrupted the seats of judgment, and rendered their persons and property insecure, and without the protection of law. Of this they complained, and made it the ground of their request for a king to judge them like all the nations- And however the Israelites might be guilty of great weakness and folly, as they certainly were, in desiring, on this account, to depart from a form of government, in which God himself presided, and wherein they might have had all their grievances redressed; and to adopt one similar to that of other nations;- and how far soever God might grant their desire, as a punishment of their ingratitude, yet, as it appears from Jacob’s blessing on the tribe of Judah, not to mention other things, it was in the divine plan, or permission at least, that the Jews, in future time, should come under the governance of earthly kings, it is no improbable conjecture, that prevailing wickedness, and corruption among some in high station at this period, was the occasion of God’s so readily complying with this request.

The passage, however, which stands at the head of our discourse, supposes the people to be judges of the good or ill effects of administration;- and as the wise king of Israel is the author, it may, perhaps, have the more weight.- “When the righteous are in authority, the people rejoice.”- They are sensible of their own happiness in having men of uprightness, honor and humanity to rule over them- Men, who make a proper use of their authority- who seek the peace and welfare of the whole community, and govern according to law and equity, or the original rules of their constitution.- “But when the wicked beareth rule, the people mourn”- they are dissatisfied and grieved when contrary to reasonable expectation, and the design they had in forming into civil society, it turns out, as the history of states and kingdoms authorizes us to say it often does, that their rulers possess opposite qualities- are inhuman, tyrannical and wicked; and instead of guarding, violate their rights and liberties.

The great end of a ruler’s exaltation is the happiness of the people over whom he presides; and his promoting it, the sole ground of their submission to him. In this rational point of view, St. Paul, that great patron of liberty, speaking of the design of magistracy, hath thought fit to place it- “he is the minister of God to thee for good”- But God’s minister he cannot be, as a ruler, however he may be in another capacity, nor is subjection required, on any other principle- his making the prosperity of the state the great object of his laws, and other measures of government, is his only claim to submission: Nor will any one deny that his doing so, and attending diligently to this very thing, binds the conscience of subjects, and makes obedience their indispensible duty. But obedience on the contrary supposition, is so far from being enjoined on them, that it argues meanness of spirit, and criminal servility, unless their circumstances are such as to make subjection a duty, on the foot of prudence, when it is not so in any other view.

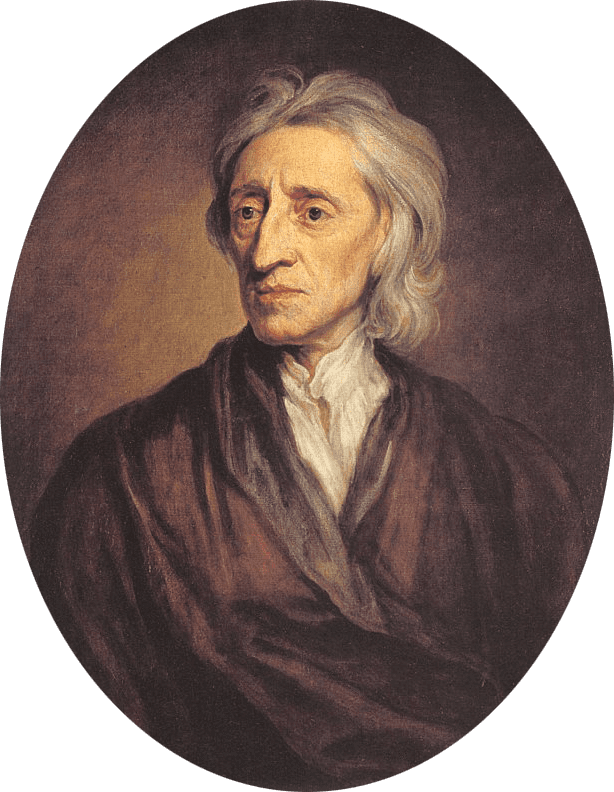

The measures which rulers pursue, are generally good or bad, promotive of the public happiness, or the contrary, as are their moral characters. The observation of our text is grounded on the truth of this assertion, though it ought to be acknowledged, that there have been wicked rulers, such as Nero, and others of later date, who, for a while, have governed well.

Whether righteousness is to be restricted merely to the virtue of justice, or considered as comprehensive of the entire character of piety and religion, where it is said, as in the place before us; “when the righteous are in authority, the people rejoice”; it may justly be affirmed that men of such a character are by far the fittest, other accomplishments being equal, to be entrusted with the civil interest of a community; and the people are the most likely to feel the salutary effects of government, and be happy in their administration.

Religious rulers are, in every view, blessings to society; their laws are just and good- their measures mild and humane- and their example morally engaging.

Veneration for the authority of the supreme ruler of the world, prevailing in their hearts, is the most effectual security of affection to the public, which is a qualification absolutely indispensible- it inspires them with principles of equity and humanity; it begets the deepest concern in all their acts of government, to answer the great intention both of God and man, in their institution, and renders them truly benefactors to mankind.

It is, however, natural to suppose, every quality necessary to the constituting a good ruler, is comprehended in the term- righteous- the observation would not, otherwise, be without exception.- The interest of a people is not always so well served by a ruler merely of a religious character, as it would be by the addition of other qualities.- Religion, indeed, ought ever to be esteemed as an indispensable recommendation to public trust; but other qualifications are also requisite, and must be joined, to afford reasonable expectation of happiness to a community, from the exercise of authority.

There does not appear to be a like reason for supposing the want of every other qualification, as that of righteousness, in the wicked ruler, to make him incapable of governing well.- He may have many and great endowments in other respects- capacity, and address-but if he has no religion- if he is immoral and vicious, unawed by him whose kingdom ruleth over all; he is commonly unfit to have the care and direction of the public interest,- If there have been instances of good government under the conduct of rulers of vicious characters, there have been also too many of a contrary sort to make it eligible or safe, to put confidence in such. To whatever lengths natural benevolence, desire of fame, education, love of power, and the emoluments of place, may be supposed sometimes to carry men, in acting for the public advantage, it is certain, and in several, it has been sadly verified, that these are feeble motives- principles, that can give no security of lasting happiness to a people, where the superior invigorating aids of religion are wanting.

The vices of a ruler pervert the due exercise of his authority, to the disadvantage of the community; and mark his public conduct with oppression and ruin. And we are not to think it strange, if the people fall into perplexity and mourning in consequence.

It is the character of one who is exalted from among his brethren, to rule over men, drawn by God himself, the Almighty guardian of the Rights of mankind- that he “must be just, ruling in the fear of God.”

The safety of society greatly depends on the good disposition of rulers, and the regard they have to equity in their measures of government. If they rule in the fear of God, they will make his laws their pattern in framing and executing their own.

Administration in every mode of government, is a point of the most weighty importance to subjects.- Absolute monarchies, or such forms of government as have the powers of the state lodged in the hands of a single person, tho’ generally dangerous to the Rights and Liberties of mankind, and too often have proved so to recommend them to the choice of a wise person, have, not withstanding, when the reigning Prince has supported the character of religion, been the source of great peace and security to the public.

But the effects have been different- distress and misery introduced into society, under the administration of one whose moral qualities have been of another complexion.

The same is true as to consequences, in those governments, where the whole power legislative and executive, is deposited with a few.- Good or evil ensues to the community, according as the exercise of their authority coincides with the eternal rulers and laws of reason and equity, or the contrary.

In a mixed government, such as the British, public virtue and religion, in the several branches, though they may not be exactly of a mind in every measure, will be the security of order and tranquility- Corruption and venality, the certain source of confusion and misery to the state.

This form of government, in the opinion of subjects and strangers, is happily calculated for the preservation of the Rights and Liberties of mankind.- Much, however, depends on union; and the concern of every part to pursue the great ends of government.

When each department centre their views in the same point, and act in their proper direction and character, as the ministers of providence, for the promotion of human happiness, things go well- the Rights of the people are secured, and they are contended- gladness fills their heart, and sparkles in their countenance!

But there may be a failure in some one or more of the governing parts, in respect to public measures, and the art of governing.- And when this happens, though it be but in one, since each part is strictly necessary to constitute the legislative body- it greatly wounds the state- embarrasses affairs- and is productive of general uneasiness and discontent.- The people soon feel inconveniences rising from jars and interference among their rulers- and as they have an indubitable right, they take it upon them, to judge what, and how far any thing is so, and where to fix the blame.

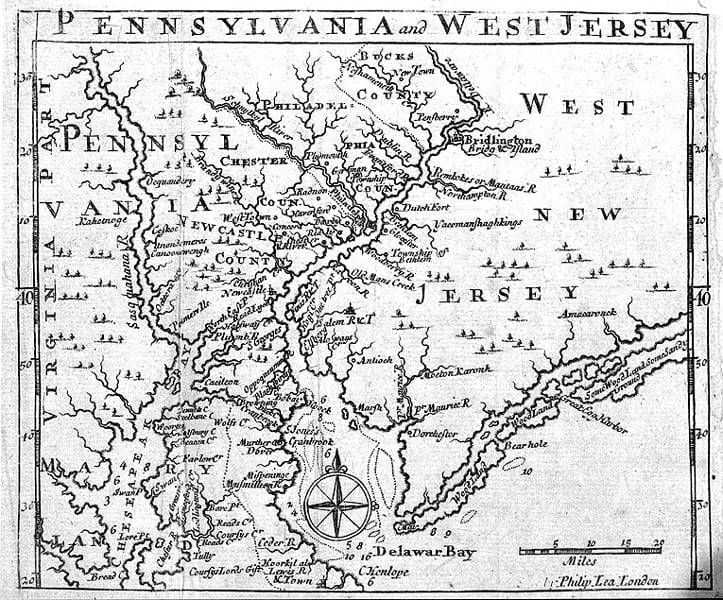

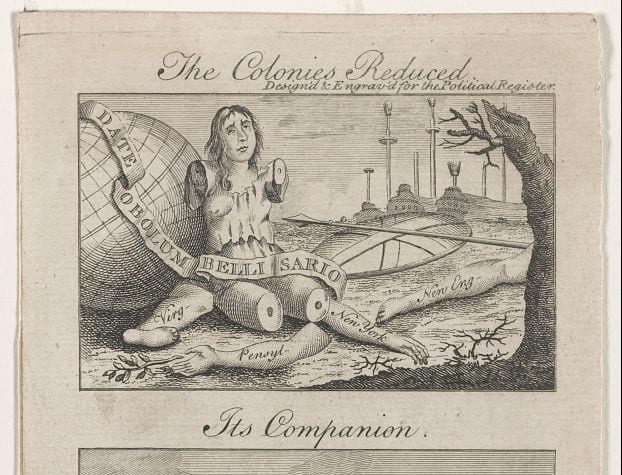

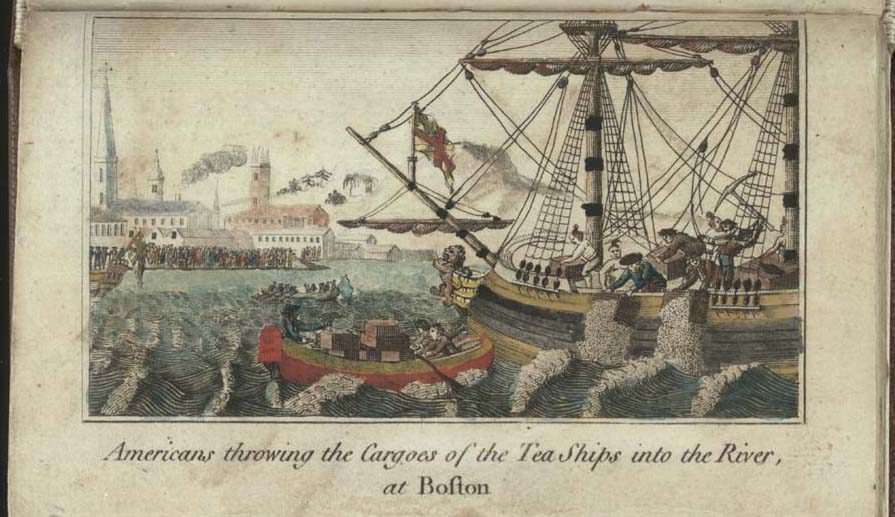

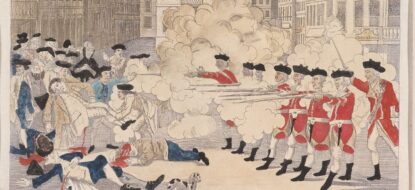

In such a government, rulers have their distinct powers assigned them by the people, who are the only source of civil authority on earth, with the view of having them exercised for the public advantage; and in proportion as this worthy end of their investiture is kept in sight, and prosecuted, the bands of society are strengthened, and its interests promoted: But if it be overlooked, and disregarded, and another set up as the object of their pursuit; we will suppose it should be, but by one of the supreme branches, or, indeed, by a single member of any, who happens to be of leading influence and great abilities, it will go far in making a schism in the body.- Calamity and distress may be expected, in a measure, to ensue- We need not pass the limits of our own nation for sad instances of this.- Whether, or how far, it has also been exemplified in any of the American colonies, whose governments, in general, are nearly copies of the happy British original, by the operation of ministerial unconstitutional measures, or the public conduct of some among ourselves, is not for me to determine: It is, however, certain, that the people mourn!- May God turn their mourning into joy! and comfort them, and make them rejoice from their sorrow!-

Rulers are under the most sacred ties to consult the good of society. ‘Tis the only grand design of their appointment. For the promotion of this valuable end, they are ordained of God, and cloathed with authority by men.

In a state of nature men are equal, exactly on a par in regard to authority; each one is a law to himself, having the law of God, the sole rule of conduct, written on his heart.

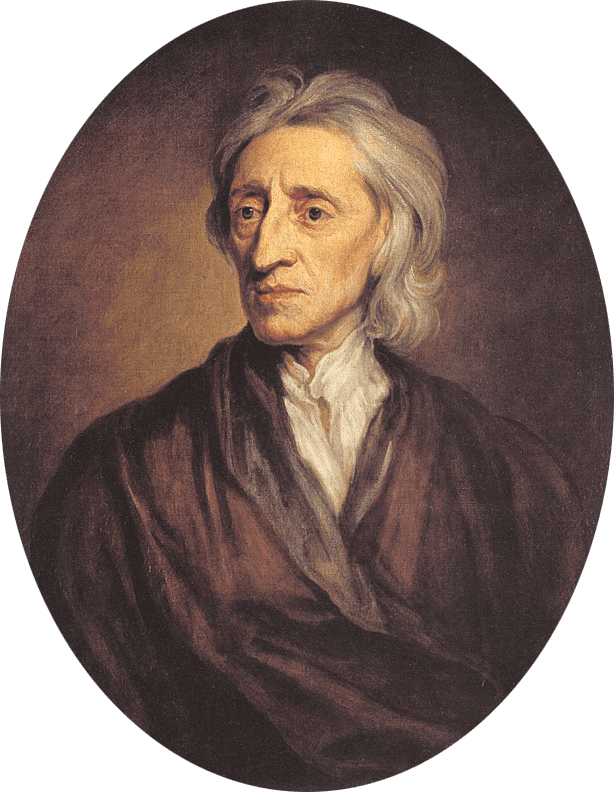

No individual has any authority, or right to attempt to exercise any, over the rest of the human species, however he may be supposed to surpass them in wisdom and sagacity. The idea of superior wisdom giving a right to rule, can answer the purpose of power but to one; for on this plan the Wisest of all is Lord of all. Mental endowments, though excellent qualifications for rule, when men have entered into combination and erected government, and previous to government, bring the possessors under moral obligation, by advice, perwasion and argument, to do good proportionate to the degrees of them; yet do not give any antecedent right to the exercise of authority. Civil authority is the production of combined society- not born with, but delegated to certain individuals for the advancement of the common benefit.

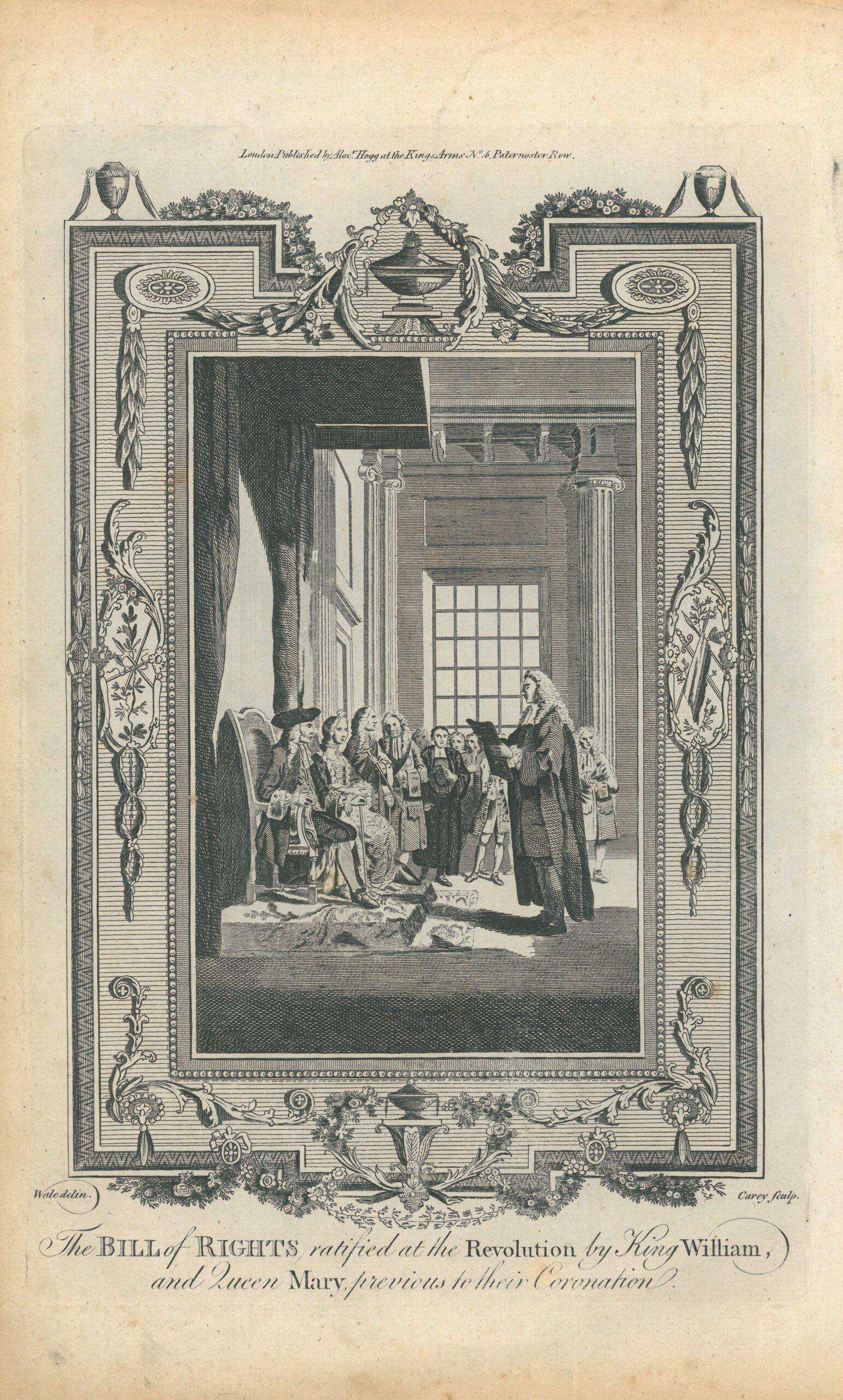

And as its origin is from the people, who have not only a right, but are bound in duty, for the preservation of the property and liberty of the whole society, to lodge it in such hands as they judge best qualified to answer its intention; so when it is misapplied to other purposes, and the public, as it always will, receives damage from the abuse, they have the same original right, grounded on the same fundamental reasons, and are equally bound in duty to resume it, and transfer it to others.- These are principles which will not be denied by any good and loyal subject of his present Majesty King George, either in Great-Britain or America- The royal right to the throne absolutely depends on the truth of them,- and the revolution, an event seasonable and happy both to the mother country and these colonies, evidently supports them, and is supported by them.

But it has been objected, that the doctrine which teaches that the people are the source of civil authority, and that they will lawfully oppose those rulers, who make an ill use of it, is likely to be attended with the worst of consequences- occasion disturbance and revolutions in the state, and render the situation of rulers perpetually unsafe and dangerous.

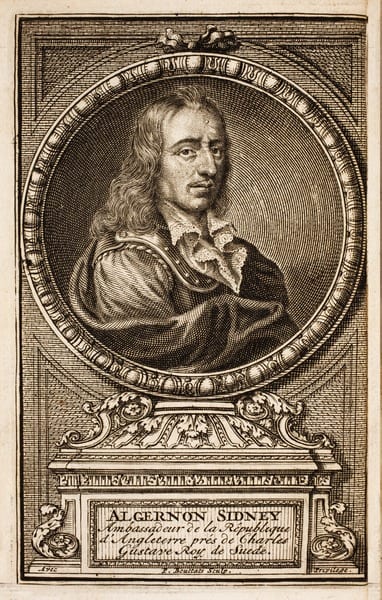

If the rulers of the latter character mentioned in our text, the safety of the community forbids any attempt or disposition to make their situation easy; and I trust the objection is without force in regard to those of the former.- It is altogether unreasonable to suppose a number of persons by a free and voluntary contract, should give up themselves, their families and estates so absolutely into the hands of any rulers, as not to make a reserve of the right of saving themselves from ruin- and if they should, the bargain would be void, as counteracting the will of heaven, and the powerful law of self-preservation. It must be granted that the people have a right in some circumstances, or that they have not a right in any, to oppose their rulers- there is no medium- A sober and rational inquiry into the consequences of each supposition, is the best method to determine on which side the truth lies- In doing this, I shall take the liberty to adopt the sentiments and nearly the words of a writer of the first class on Government.

If it be true that no rulers can be safe where the doctrine of resistance is taught; it must be true that no nation can be safe where the contrary is taught: If it be true that this disposeth men of turbulent spirits to oppose the best rulers; it is as true that the other disposeth princes of evil minds, to enslave and ruin the best and most submissive subjects: If it be true that this encourageth all public disturbance, and all revolutions whatsoever; it is as true that the other encourageth all tyranny, and all the most intolerable persecutions and oppressions imaginable. And on which side then will the advantage lie?- And which of the two shall we chuse, for the sake of the happy effects and consequences of it?

Supposing it to be universally admitted, that if rulers contrive and attempt the ruin of the publick, it is the duty of the people to consult the common happiness, and oppose them in such a design; it must follow, I think, that the grounds of publick unhappiness would be removed, and those inconveniences, which by mistake are represented as the consequences of this doctrine, prevented; for, on this supposition, the worst of Princes would learn to do that out of interest, which the best constantly do out of a good principle and true love to their subjects- No Prince would have any persons about him, to advise and incite him to illegal or unjust actions- and if he had at any time been guilty, he would, upon the first representation, and without being forced to it, readily acknowledge his error, and set all things right again. And let who will say it, the dispositions of subjects are not so bad, nor their love to public disturbance so great, but that a Prince of such conduct may be sure of reigning in their affections, and of being obeyed out of love and gratitude; which is the securest foundation any throne can possibly be fixed on.- So far is it from being true, that the universal reception of the doctrine of resistance would be the ground of public confusion and misery, that it would prevent the beginning of evil, and take away the first occasion of discontent.

It must be acknowledged, it is because this doctrine, whatever is pretended, hath not been received, that any rulers have been misled, and encouraged to take such measures, as in the end, have proved fatal to themselves. With respect therefore to rulers of evil dispositions, nothing is more necessary than that they should believe resistance, in some cases to be lawful. In intend not for a few discontented individuals who may happen to take it into their heads to resist, but for the majority of a community, either by themselves or representatives. Such rulers, indeed, cannot bear the propagation of this doctrine; but the reason why they cannot, viz. its being preventive of their pernicious designs, is an undeniable argument of its being the more necessary.

As for good rulers, they are not affected by the propagation of it, but may promote it themselves consistently with their own particular interest; for it is the chief interest of princes to reign in the affections of their subjects, free from all suspicion and jealousy of evil design. Nothing can give a nation greater satisfaction that their supreme magistrate sincerely endeavors to promote their interest, or gain him more hearty love and esteem, than the admission of this doctrine; it looks open, and removed from base and unworthy purposes; but a zeal for the opposite doctrine, tends, in its nature, and has been seen, in experience, to create jealousies in the minds of subjects, to take off their affections from a prince, and to lay the foundation of their withdrawing their allegiance from him.

But supposing it to be universally received, that it is the duty of the people patiently to submit, and not oppose their rulers, tho’ manifestly carrying forward the ruin of the public, nothing can be imagined to follow, but what is of the worst consequence to human society, unless we suppose rulers as angels of God, or rather, as God himself, incapable of being mistaken themselves, or misled by others. This supposition leaves no restraint on such rulers as have designs of their own, distinct from the public good: Public misery and slavery will therefore ensue; and this is a state of things infinitely worse than that of public disturbance, supposing such sometimes to take place in consequence of resistance. The inconveniences of the latter will soon be felt and rectified by the people themselves; but the former, on the principle of non-resistance, is absolutely without a remedy.

When people feel the influence and blessing of a good administration, they are not, in general, disposed to complain and find fault with their rulers; it is inconsistent with their own interest, and that f their families to do so. If we will be determined on a point of such delicacy by a ruler himself, who, as absolute as he was, had wisdom and public virtue to give judgment conformable to the nature and truth of things, we shall see that it is under the influence of an evil administration the people are discontented and mourn; and that under the influence of a good, one they rejoice.

All lawful rulers are the servants of the public, exalted above their brethren not for their own sakes, but the benefit of the people; and submission is yielded, not on the account of their persons considered exclusively of the authority they are clothed with, but of those laws, which in the exercise of this authority are made by them, conformably to the laws of nature and equity.

This position is so far from being unacceptable to good rulers, or thought to be derogatory of their dignity, that they esteem it as implying the highest human character, and an official resemblance of the great Savior of mankind, who came not to be ministered unto, but to minister; and accordingly went about doing good.

The assertion that rulers are constituted by the people for the common happiness, is no denial of St Paul’s doctrine, who, speaking of magistracy, hath said- There is no power but of God; the powers that be are ordained of God:- any more than it is a denial of the blessings of husbandry, merchandize, and the mechanic arts, or, indeed any thing beneficial to society, being from God, to say, that men have invented them- They are all from God, from whom cometh down every good and perfect gift; and much in the same sense, as it is his will that men should be employed in them for their own advantage: But men by their reason, which is also the gift of God, are the immediate discoverers of their utility. It is, however, necessary to observe, that as civil governments holds a distinguished place among the gifts of God; and, considering the human make, the blessings of it are productive of a greater aggregate of happiness, both in a natural and moral view, than most others: Much has been said in revelation about it- the divine approbation manifested- and the qualification of rulers exactly stated.

Although government is not explicitly instituted by God, it is, nevertheless, from him; as, by the human constitution, and the circumstances men are placed in, He has signified it to be his will, that, as a security of property and liberty, and as necessary to greater improvements in virtue and happiness than could be attained in a state of nature, there should be government among them. But it is from man, as for the same end- the procuring a greater good to each individual, on the whole, than could be had without it; they have, in conformity to their make and circumstances, and the dictates of reason, voluntarily instituted it. And thus government is the ordinance both of God and man. And so the new-testament writers consider it, and speak of its design as being the same in both, viz. The public happiness.

This is a striking indication to rulers, not only as to their aims in accepting any public office in a community, but as to the obligations they are under to discharge the duties of it with fidelity. They are the trustees of God, vested with authority by him, in the benevolent designs of his providence, to be employed in guarding and defending the just Rights and Liberties of mankind; and as far as they can, advancing the common welfare.

And as they are responsible to him who is no respecter of persons; they are not to expect their public conduct is to be exempted from his most strict and impartial scrutiny.

They are also the trustees of society, as their authority, under God, is derived from the people, delegated to them with design it should be exercised for, and to no other purpose than, the common benefit; and this renders them justly accountable to their human constituents, whose tribunal, however some have affected to despise it, is full of dignity and majesty- Kings and emperors have trembled before it!

While merely to possess places of dignity and eminence is sufficiently gratifying to some minds, the chief joy of rulers, mindful of the importance of their station, arises from a consciousness of such behaviour, in their public capacity, as will be approved of God, and accepted of men. For this great and valuable purpose, they will be careful to deserve the character first mentioned in the text- be just and impartial in every part of administration; and with their integrity, endeavor to join those other accomplishments which are requisite to the honorable discharge of their respective trusts.

But this brings us in the second place to point out some of the qualifications of rulers.

And superior knowledge may be mentioned as one, that greatly exalts and adorns their character.

They should, therefore, be ambitious to become possessed of it, that they may be at no loss how to conduct, or which way to turn themselves in any difficult and embarrassed state of affairs; but may know what the people ought to do, and be able and ready to lead and advise them in the more boisterous and alarming, as well as in calm and temperate seasons.

Distinguished abilities and knowledge, tho’ happily placed in rulers, are not indeed so absolutely necessary, in order to understand the constitution, or the general rules of any particular mode of government a people have chosen to put themselves under, as for other important matters in administration.

All fundamental laws and rules of government are, in their nature and design, and ever ought to be, plain and intelligible- such as common capacities are able to comprehend, and determine when, and how far they are, at any time, departed from. Were not this the case, people’s entering into society, and erecting government, could not be justified on the principle of reason, or prudence; as government instead of protecting them in the peaceable and quiet enjoyment of Liberty and property, might be made an engine of their destruction, and put it in the power or rulers of evil dispositions, under the specious pretext of pursuing constitutional measures, to introduce general misery and slavery among them.

The knowledge which the people have of the constitution, or original fundamental laws of government, whereof the plain law of self-preservation is necessarily the chief, in all forms of government, is the only adequate check on such ruinous conduct.

The people being judges of their own constitution of government, is the principle from which the British nation acted, and on the truth of which they are to be justified, when they determined, their constitution was invaded by their sovereign, and that he was carrying on designs, which if pursued, must issue in the destruction of it.

But if they were no judges of such matters, if they meddled with that which did not belong to them- the revolution, and succession of an illustrious house, may have taken place without right, against law and reason, being founded in misconception and error; and the heirs of an abjured popish prince, still remain the only just, and lawful claimants to the British throne; a doctrine, which, I am sure, no American, and I hope, but few in great Britain, will ever admit. If the foundations be destroyed, what can the righteous do?

But high degrees of knowledge are requisite in rulers for other great and weighty purposes in government. If they would act with dignity and advantage in their public capacity, they should be well acquainted with human nature, and the natural rights of mankind; which are the same under every form of government: They should also be acquainted with the general rules of equity and reason, and the right application of them, as circumstances vary; with the laws of nations, their strength, manners, and views; but especially with the genius, temper, customs and religion of the people they are called to govern: This will enable them to accommodate public measures to public advantage, and to frame such laws and annex such sanctions, from time to time, as may be best calculated to encourage piety and virtue, industry and frugality, and prevent immorality and vice, and every species of oppression and misery- They should moreover know, in what instances natural equity and a regard to the good of the whole require former laws to be repealed, or varied- new ones enacted, and other penalties applied, and in what way government may be the most effectually, honorably and easily supported.

Legislators, whom I have chiefly had in view, should know how to give force, and operation to their laws, that every member of the community may feel their effects, and be treated in a just and reasonable manner; and as far as may be, according to his personal circumstances and merits. This, indeed, is to be done by means of the executive part, but the executive power is strictly no other than the legislative carried forward, and of course, controulable by it.- These, and others that might be adduced, are points requiring capacity and knowledge in rulers: And among other means for the attaining them, it is their indispensible duty, in imitation of a wise king, to pray for an understanding heart, that in all their acts of government, they may discern between good and bad, and lead the people in the paths of righteousness and peace.

Another qualification, is a public spirit, and a compassionate regard to mankind.

When we take into consideration the great design of civil government, no one can be thought a proper person to rule over men, who has not a prevailing regard to their interest, and a fixed determination to pursue it.

This, certainly is the great object which magistrates, as such, are under obligation to keep in their eye- as men, they have, like other men, private interest, and private views, and may be as lawfully pursue them; but in their public capacity, they can, of right, have no other end, than the public advantage.

And if they make use of their authority, or the influence of their rank for any different purposes- if it be their chief aim to aggrandize themselves, their posterity or friends by means thereof; if the selfish passions predominate and guide and determine their public conduct; if they are slaves to covetousness, ambition or effeminacy; if, led by flattering prospects, they are devoted to the meer will, and arbitrary mandates of others greater and higher than themselves; if there be any thing they are more solicitous to obtain or promote than the good of the society they are connected with, and are bound to serve,- they ignominiously prostitute their trust, and basely counteract the main design of their institution.

But rulers of a patriotic spirit are actuated by better and more noble principles; they have a sincere regard to the public; their time and abilities are cheerfully employed in the promotion of its interest; this they set up as the object of their measures, and esteem it as their own good, they seek the prosperity of the people, and in the peace thereof they shall have peace-The honors and emoluments of their station, though justly due and freely rendered by a sensible, obliged and grateful people, are but inferior motives with them- happy such rulers in the applauses of the multitude, happy in the approbation of their own minds!

But that which compleats the character of rulers and adds luster to their other accomplishments, is religion.

This is the best foundation of the confidence of the people; if they fear God, it may be expected they will regard man. Vice narrows the mind and bars the exertions of a public spirit; but religion dilates and strengthens the former, and gives free course to the operations of the latter.

By religion I would be understood to intend more than a bare belief of the divine existence and perfections- The heathen world by a proper use of their reason may attain to this, because that which may be known of God is manifest in them, for God hath shewed it unto them.

But what I intend by religion is, a belief of the truth as it is in Jesus, and a temper and conduct conformable to it.

It is the wisdom of christian states, to have christian magistrates, and as far as may be, such as have imbibed the spirit of the gospel, and are actuated in their high station, by the principles it inspires. If it be allowed, as to be sure it ought, that magistrates of deistick principles, may have a regard to the civil interest of mankind, and do many worthy deeds for society; it must also be allowed that they are not so likely, as those of christian principles, to be nursing fathers to the church of Christ, which, agreeable to ancient prophecy, magistrates, under the present dispensation of the divine grace, are obliged to be.

Nor will they be so much concerned to learn from the sacred oracles, for the guidance of public measures, what is the good, and acceptable, and perfect will of God.

When a people have rulers set over them, of a religious character on the gospel plan- who own and submit to Jesus Christ as their Lord and Saviour, who are sanctified by the divine spirit and grace, and, in a good measure, purified from those corrupt principles which too often work in the human heart, they have reason to expect the presence and blessing of God will be with them, and that things will go well in the state.

And on reflection, we cannot forbear the acclamation of the psalmist- happy is that people, that is in such a case!- yea, happy is that people whose God is the Lord!

The religion of rulers is a guide to their other accomplishments- it has a salutary active influence into all their measures of government, and leads them to the noblest exertions for the advancement of the common weal.

The minds of the governed are satisfied with their conduct, rejoice in their administration, and rest assured that no harm will ever happen to them, by their means, unless it be by mistake, to which all men are liable. By the blessing of the upright the city is exalted, but it is overthrown by the mouth of the wicked.

We come now- thirdly- to apply the subject to ourselves, and the occasion of our present assembling.

It would be as much beyond my expectation, as, I am sure it is short of my design, to be charged with the meanness of adulation, in any thing delivered in this discourse.

But I could not obtain forgiveness of my own mind nor of the public, if I should forbear explicitly to affirm, that the two honorable branches of the legislature, we before have had, which derived their political existence more immediately from the people, have been in their general conduct and measures, but especially in the late months and years of our distress and controversy, accepted of the multitude of their brethren.

It is our ardent wish and confidence, the same vigilance, circumspection and public spirit, may distinguish the proceedings of the two houses of assembly for the current year- that which is now returned, with marks of approbation and honor, from their constituents, and the other which according to royal charter, is this day to be chosen.

This anniversary, which is so auspicious to the civil liberties of this province, fills every honest heart with joy and gladness, and I trust with the sincerest gratitude to almighty God, the great patron of liberty, and benefactor of the world.

The choice of persons from among ourselves, to sit at council board, both in a legislative capacity, and as his majesty’s council to give their advice to his representative here, on all matters of government, as circumstances may require, we esteem a great security of our natural rights; and one of our most invaluable privileges- a privilege, which we never have forfeited, and we are resolved we never will, or voluntarily resign it into the hands of any of our fellowmen- though it must be acknowledged, I speak it with shame and blushing, that for the many crying sins, and enormities committed in our land, it would be righteous in the divine government, if we were deprived of this and all our mercies.

The appointment of one to fill the chair, is, by royal charter, reserved to the crown. Of this we have not been much disposed to complain; for though we remember our first charter with affection, and the arbitrary despotic manner of its dissolution with abhorrence, yet we have been used to put great confidence in the paternal goodness of our gracious sovereigns; and to expect such governors to be appointed over us, as would seek the peace and welfare of this people; and however it might be thought possible for them, in any future time to receive such orders from the higher servants of the crown, as would be inconsistent with our rights and privileges, we have supposed, notwithstanding they would consider themselves as being under prior obligations to the king of kings, and obey God, rather than men.

We have been used to think they would esteem the service of his majesty within this province, and the good of the province, as being the same, and that it is as impossible for his majesty to have any good in America, separate from the good of his American subjects, as it is to have any good in Great-Britain separate from the good of his British subjects.

The end of government, certainly, requires men of such dispositions and sentiments to rule over this people. Prerogative itself is not a power to do any thing it pleases, but a power to do some things for the good of the community, in such case as promulgated laws are not able to provide for it.

On these principles it is reasonable to expect that his Excellency who is lately appointed to the government of this province, and of whose candor and moderation we have heard with pleasure, will enter on the duties of his high station, with honor to himself and advantage to the publick, and make the happiness of this people the great object of his administration which is the surest way to conciliate their affections, and establish his own authority. We wish his Excellency much of the divine presence and guidance- the supports of religion- and the plaudit of his final Judge.

The honourable Gentlemen, who are, this day, to be concerned in the exercise of an important charter privilege, the election of his Majesty’s Council; will not, ’tis presumed, be unmindful of the very interesting nature of this publick transaction, nor how far its influence may extend.

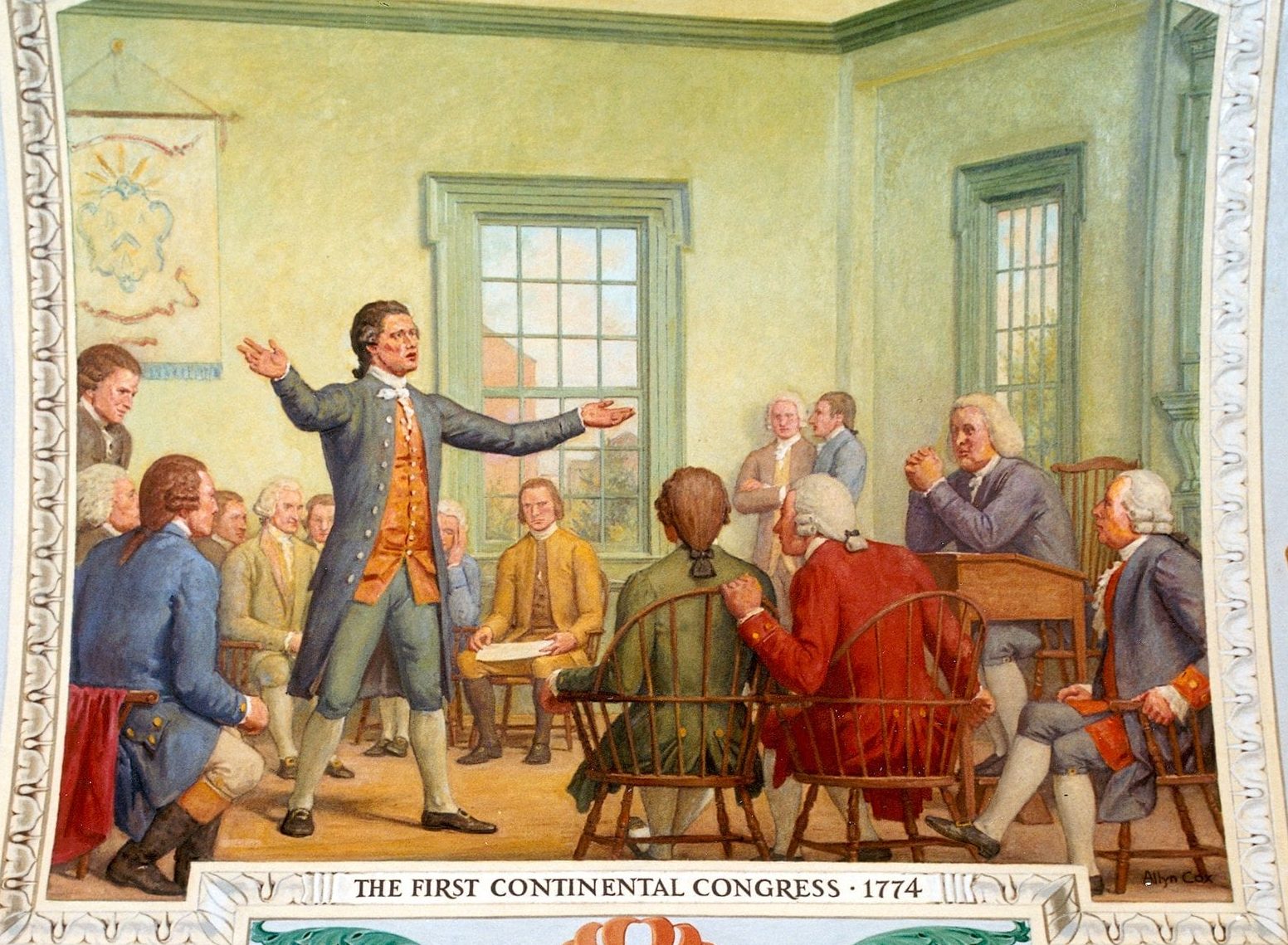

Much lies at stake, honored Fathers- much depends, and will probably turn on the choice you make of Councellors, not to this province only, but to the rest of the colonies. In the present scenes of calamity and perplexity, when the contest in regard to the rights of the colonists, rises high, every colony is deeply interested in the public conduct of every other.

The happy union and similarity of sentiment and measures which take place thro’ the continent in regard to our common sufferings, and which have added weight to the American cause, must be cherished by every prudent and constitutional method, and will, we trust, meet with your countenance and cultivation.

The acknowledged weight of the Council Board, in the government of this province, and its influence into the well-being of our churches, from its connection with, and inspection over a very respectable seminary of learning, are not your only motives. But the united voice of America, with the solemnity of thunder and with accents piercings as the lightning awakes your attention, and demands fidelity.

The ancient advice dictated to Moses, by the priest of Midian, and approved of God, is admirably calculated, civil Fathers, for your direction on this occasion- Tis a significant compendium of the qualifications of the persons whom you ought to favor with your suffrages.- Thou shalt provide out of all the people, able men- such as fear God, men of truth, and hating covetousness, and place such over them.

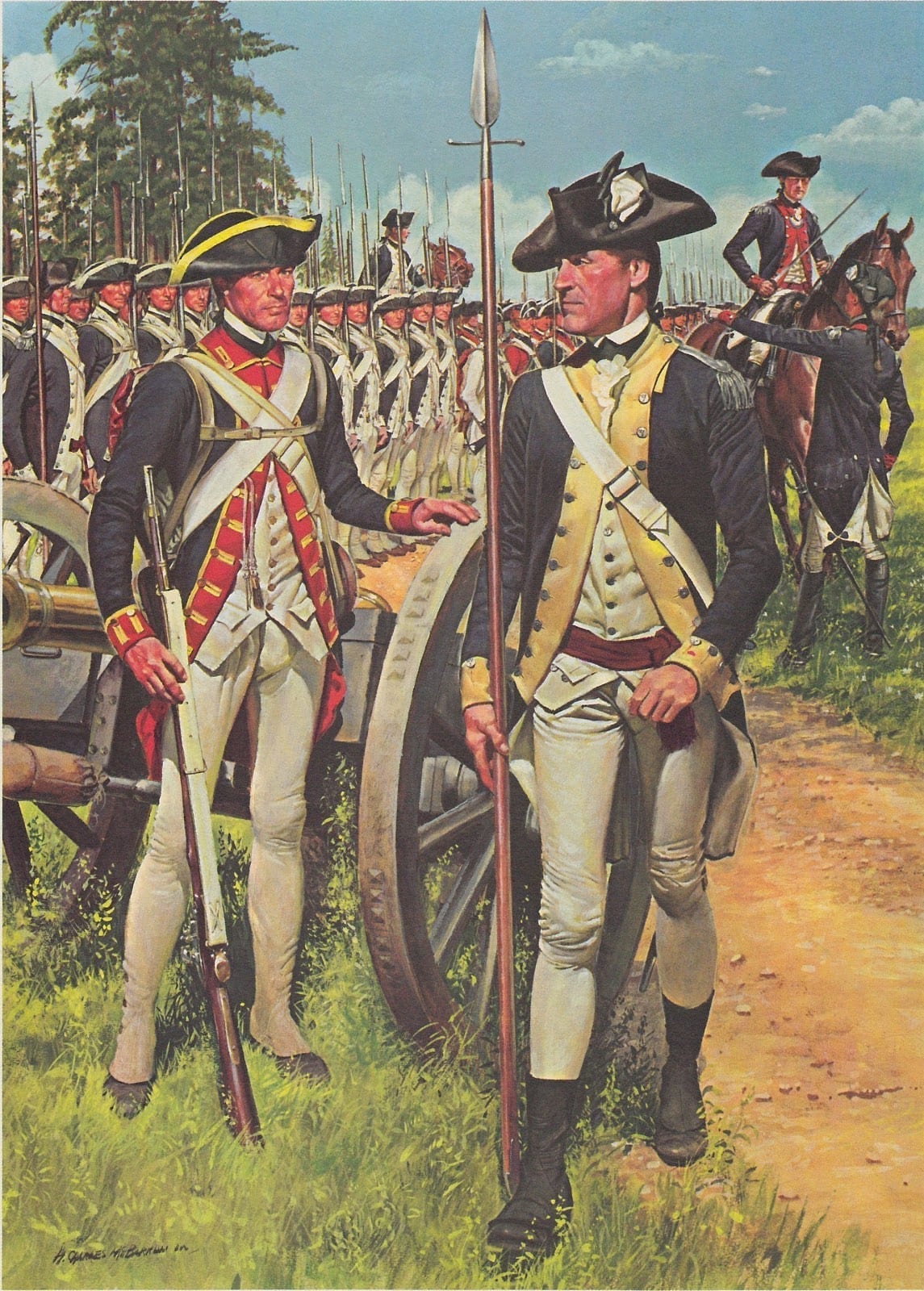

The present situation of our public affairs requires good degrees of knowledge, firmness of spirit, patriotism, and the fear of God, in those who stand at helm and guide the state- they should be men able to investigate the source of our evils, point out adequate remedies, and that have resolution and public spirit to apply them.

Our danger is not visionary, but real- Our contention is not about trifles, but about liberty and property and not ours only, but those of posterity, to the latest generations. And every lover of mankind will allow that these are important objects, too inestimably precious and valuable enjoyments to be treated with neglect, and tamely surrendered:- For however some few, I speak it with regret and astonishment, even from among ourselves, appear sufficiently disposed to ridicule the rights of America, and the liberties of subjects; ’tis plain St. Paul, who was a good judge, had a very different sense of them- “He was on all occasions for standing fast, not only in the liberties with which Christ had made him free, from the Jewish law of ceremonies, but also in that liberty, with which the laws of nature, and the Roman state, had made him free from oppression and tyranny.”

If I am mistaken in supposing plans are formed, and executing, subversive of our natural, and charter rights, and privileges, and incompatible with every idea of liberty, all America is mistaken with me.

Our continued complaints- Our repeated, humble, but fruitless, unregarded petitions remonstrances- and if I may be allowed the sacred allusion, our groaning, which cannot be uttered, are at once indications of our sufferings, and the feeling sense we have of them.

We think we are injured- We believe we are denied some of those privileges, enjoyed by our fellow subjects in Great-Britain, which have not only been insured to us by Royal Charter, but which we have a natural independent right to.

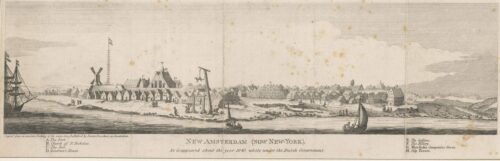

And it bears the harder on our spirits, when we recollect the deep inwrought affection we have always had for the parent state- our well known loyalty to our Sovereign, and our remitting attachment to his illustrious house, as well as the ineffable toils, hardships and dangers which our Fathers endured, unassisted, but by Heaven, in planting this American wilderness, and turning it into a fruitful field!

But in such circumstances, we place great confidence in the wisdom and patriotism of our civil rulers- Our eyes are fixed on them, and under the smiles of Heaven we expect a redress of our grievances by their instrumentality. Or, at least, that they will not be wanting, in any thing in their power, consistent with the duties of their station, to effect it.

We sincerely hope, and trust, the elections of this day will turn on men, who shall be disposed in their proper department to restore and establish our rights- Men acquainted with the several powers vested in the honorable board, and determined, with persevering spirit, to assert and uphold them- Men, in every view, friendly to the constitution of government in this province, and resolved to maintain it, undiminished, and entire.

You will please to remember, Gentlemen, that in this weighty affair, you do not act merely for yourselves- you act for the whole community- every member has an interest in the transaction.

But above all, suffer me to remind you, that you act for God, and under his inspection, by whose providence, this trust is committed to you- and that you must one day give an account to Him whose eyes are as a flame of fire, of the motives of your conduct.

When the business of the day is finished,- the legislative body will enquire into the interior state of the province, and enter upon public concerns relative to the well ordering, and directing its affairs.

But whether circumstances require any new laws to be enacted, or new regulations, in any respect, made, we willingly refer to the superior wisdom and conduct of the guardians of our common interest- I would, however, take the liberty to say, that the public good, the peace, and prosperity of this province, ought ever to lie near your hearts, and be kept in view, as the polar star, by which all your debates, and governmental acts, are to be directed.

And if you can do any thing more effectual, than has yet been done, to prevent the too general prevalence of vice, and immortality, and promote the knowledge and practice of religion and godliness among us, you will perform great good service for the public- you will, hereby, give us the highest reason to hope, and believe, that our infinitely good and gracious God, the tenor of whose providence, hath always, from the beginning, and remarkably in the days of our New-England progenitors, been favorable to his people, in times of calamity and darkness, will make bare his arm, and deliver us from our public embarrassments- Righteousness exalteth a nation- but sin is the reproach, and if continued, will be the ruin of any people.

But if you can do no more for so excellent a purpose; let us, notwithstanding, for your own sakes, and for ours, be assured of the benefit of your example.

We are easily led by the example of our superiors, whom we respect and revere, and when it is turned on the side of religion and virtue, it cannot fail of happy influence into the religion of our minds, and the morality of our lives.

Did men of exalted station and characters, consider how much it is in their power to reform or corrupt the age,- the lower ranks and classes of mankind, we might expect a conduct from them, that would teach us, to connect the ideas of greatness and religion,- at least, more nearly than we too generally have done.

We are therefore, willing to think, as we sincerely wish, that from a proper zeal for the divine glory, and a generous regard to their fellow men, our civil fathers will go before us in the uniform practice of pure religion, and undefiled, before God and the Father.

Under the administration of rulers of such a character, we shall not rejoice merely in a civil view, but in the prosperity of our souls shall we be glad; and rejoice before God, exceedingly.

Before I close, I may not omit putting the whole body of this people in mind to be subject to principalities and powers, and to obey magistrates.

This is the direction to Titus by the same Apostle, who in another Epistle has limited the obedience of subjects, to such rulers as answer the end of their appointment: the like limitation is therefore to be understood here- To such magistrate as rule well, who are a terror, not to good works, but to the evil, which is the reason St. Paul has assigned why subjects are obliged, in point of conscience, to submit to them- to such magistrates, I say, the most cheerful obedience is due from the people as being the greatest blessings society can enjoy- and to withhold obedience from such, is the greatest of crimes, as it directly tends to public confusion and ruin.

As a people we have ever been remarkably tender of our civil and religious liberties; and ’tis hoped, the fervor of our regard for them, will not cool, till the sun shall be darkened, and the moon shall not give her light.

But justice to ourselves requires us to say, that we have been as remarkable for our steady, uniform submission to those who have had the rule over us.

If it should be affirmed that no instance of general complaint and uneasiness has been known among us from the settlement of our Fathers in America, but when our liberties have been evidently struck at, I believe, impartial history would support the sentiment.

If we have complained, we have had too manifest occasion for it; and all writers on government but those of a rank, arbitrary, popish complexion, allow of complaints, and remonstrances, and even opposition to measures, in free governments, which the people know to be wrong; and indeed were not this the case, there would soon be no such governments on the earth.

The people in this province, and in the other colonies, love and revere civil government- they love peace and order but they are not willing to part with any of those rights and privileges, for which they have, in many respects, paid very dear.

The soil we tread on is our own, the heritage of our Fathers, who purchased it by fair bargain of the natives, unless I must except a part, which they afterwards in their own just defence, obtained by conquest- We have therefore an exclusive right to it.

For, how far soever discovery may operate, in acquiring a right in wild uninhabited countries; every one must allow it could acquire none in this inhabited, as it was, who is not willing to grant, that the native of America would have acquired as good a right to Great-Britain or any part of Europe, if their navigation had been able, at the same time, to have wafted them in sight of it.

But while we are disposed to assert our rights, and hold our liberties sacred, let us not decline from our former temper, and despise government; but may we always be ready to esteem and support it, in its truest dignity and majesty. Let us respect and honor our civil rulers, and as much as possible lighten their burdens by a cheerful obedience to their laws, without which the great end of government, the public safety and happiness, cannot be promoted.

Under the pressing, growing weight of our public troubles and difficulties our hearts, tho’ perplexed, have not fainted- We wait for the salvation of God- It is better to trust in the Lord than to put confidence in princes- Let us go on to trust in him, ’till God himself shall rise to save us- Let us not divide and crumble into parties, on little irregularities, which, however aggravated by some, are, in our circumstances, almost unavoidable. But may we have that wisdom which is profitable to direct, and distinguish between what has, and what has not, a tendency to remove our burdens and prolong our just rights and liberties; especially, let us be on our guard against a spirit of licentiousness, which is the reproach of true liberty, and has been the overthrow of free governments.

And by whatever titles and characters we may be distinguished, in the limited governments of this world, let us bear it on our hearts, that we are all subjects of the divine, universal government, which is administered in righteousness; and must shortly render an account of our conduct under it to God, the judge of all.

If this important consideration was duly impressed on the minds of all ranks and orders of men, it would lead us to acquire and cultivate the spirit of the gospel, which is a spirit of love and benevolence, and beget a conduct, which while it ripens us thro’ grace for immortality and glory, would be greatly promotive of the present benefit of human society.-

And when, by the efficacious influence of the blessed spirit, our rational and immortal part is established in its just supremacy- when our appetites and passions are subject to its authority, and our desires regular, modest & just- Then shall our righteousness go forth as brightness, and our salvation as a lamp that burneth.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.