No study questions

No related resources

The History of Liberalism

Liberalism has long been accustomed to onslaughts proceeding from those who oppose social change. It has long been treated as an enemy by those who wish to maintain the status quo. But today these attacks are mild in comparison with indictments proceeding from those who want drastic social changes effected in a twinkling of an eye, and who believe that violent overthrow of existing institutions is the right method of effecting the required changes. From current assaults, I select two as typical: “A liberal is one who gives lip approval to the grievances of the proletariat, but who at the critical moment invariably runs to cover on the side of the masters of capitalism.” Again, a liberal is defined as “one who professes radical opinions in private but who never acts upon them for fear of losing entrée into the courts of the mighty and respectable.” Such statements might be cited indefinitely. They indicate that, in the minds of many persons, liberalism has fallen between two stools, so that it is conceived as the refuge of those unwilling to take a decided stand in the social conflicts going on. It is called mealy–mouthed, a milk–and–water doctrine and so on.

Popular sentiment, especially in this country, is subject to rapid changes of fashion. It was not a long time ago that liberalism was a term of praise; to be liberal was to be progressive, forward–looking, free from prejudice, characterized by all admirable qualities. I do not think, however, that this particular shift can be dismissed as a mere fluctuation of intellectual fashion. Three of the great nations of Europe have summarily suppressed the civil liberties for which liberalism valiantly strove, and in few countries of the Continent are they maintained with vigor. It is true that none of the nations in question has any long history of devotion to liberal ideals. But the new attacks proceed from those who profess they are concerned to change not to preserve old institutions. It is well known that everything for which liberalism stands is put in peril in times of war. In a world crisis, its ideals and methods are equally challenged; the belief spread that liberalism flourishes only in times of fair social weather.

It is hardly possible to refrain from asking what liberalism really is; what elements, if any, of permanent value it contains, and how these values shall be maintained and developed in the conditions the world now faces. On my own account, I have raised these questions. I have wanted to find out whether it is possible for a person to continue, honestly and intelligently, to be a liberal, and if the answer be in the affirmative, what kind of liberal faith should be asserted today. Since I do not suppose that I am the only one who has put such questions to himself, I am setting forth the conclusions to which my examination of the problem has led me. If there is danger, on one side, of cowardice and evasion, there is danger on the other side of losing the sense of historic perspective and of yielding precipitately to short–time contemporary currents, abandoning in panic things of enduring and priceless value.

The natural beginning of the inquiry in which we are engaged is consideration of the origin and past development of liberalism. It is to this topic that the present chapter is devoted. The conclusion reached from a brief survey of history, namely, that liberalism has had a chequered career, and that it has meant in practice things so different as to be opposed to one another, might perhaps have been anticipated without prolonged examination of its past. But location and description of the ambiguities that cling to the career of liberalism will be of assistance in the attempt to determine its significance for today and tomorrow.

The use of the words liberal and liberalism to denote a particular social philosophy does not appear to occur earlier than the first decade of the nineteenth century. But the thing to which the words are applied is older. It might be traced back to Greek thought; some of its ideas, especially as tot the importance of the free play of intelligence, may be found notably expressed in the funeral oration attributed to Pericles. But for the present purpose it is not necessary to go back of John Locke, the philosopher of the “glorious revolution” of 1688. The outstanding points of Locke’s version of liberalism are that governments are instituted to protect the rights that belong to individuals prior to political organization of social relations. These rights are those summed up a century later in the American Declaration of Independence: the rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Among the “natural” rights especially emphasized by Locke is that of property, originating, according to him, in the fact that an individual has “mixed” himself, through his labor, with some natural hitherto unappropriated object. This view was directed against levies on property made by rules without authorization from the representatives of the people. The theory culminated in justifying the right of revolution. Since governments are instituted to protect the natural rights of individuals, they lose claim to obedience when they invade and destroy these rights instead of safeguarding them: a doctrine that well served the aims of our forefathers in their revolt against British rule, and that also found an extended application in the French Revolution of 1789.

The impact of this earlier liberalism is evidently political. Yet one of Locke’s greatest interests was to uphold toleration in an age when intolerance was rife, persecution of dissenters in faith almost the rule, and when wars, civil and between nations, had a religious color. In serving the immediate needs of England–and then those of other countries in which it was desired to substitute representative for arbitrary government–it bequeathed to later social thought a rigid doctrine of natural rights inherent in individuals independent of social organization. It gave a directly practical import to the older semi–theological and semi–metaphysical conception of natural law as supreme over positive law and gave a new version of the old idea that natural law is the counterpart of reason, being disclosed by the natural light with which man is endowed.

The whole temper of this philosophy is individualistic in the sense in which individualism is opposed to organized social action. It held to the primacy of the individual over the state not only in time but in moral authority. It defined the individual in terms of liberties of thought and action already possessed by him in some mysterious ready-made fashion, and which it was the sole business of the state to safeguard. Reason was also made an inherent endowment of the individual, expressed in men’s moral relations to one another, but not sustained and developed because of these relations. It followed that the great enemy of individual liberty was thought to be government because of its tendency to encroach upon the innate liberties of individuals. Later liberalism inherited this conception of a natural antagonism between the individual and organized society. There still lingers in the minds of some the notion that there are two different “spheres” of action and of rightful claims; that of political society and that of the individual, and that in the interest of the latter the former must be as contracted as possible. Not till the second half of the nineteenth century did the idea arise that government might and should be an instrument for securing and extending the liberties of individuals. This later aspect of liberalism is perhaps foreshadowed in the clauses of our Constitution that confer upon Congress power to provide for “public welfare” as well as for public safety.1

What has already been said indicates that with Locke the inclusion of the economic factor, property, among natural rights had a political animus. However, Locke at times goes so far as to designate as property everything that is included in “life, liberties and estates”; the individual has property in himself and in his life and activities; property in this broad sense is that which political society should protect. The importance attached to the right of property within the political area was without doubt an influence in the later definitely economic formulation of liberalism. But Locke was interested in property already possessed. A century later industry and commerce were sufficiently advanced in Great Britain so that interest centered in production of wealth, rather than in its possession. The conception of labor as the source of right in property was employed not so much to protect property from confiscation by the ruler (that right was practically secure in England) as to urge and justify freedom in the use and investment of capital and the right of laborers to move about and seek new modes of employment–claims denied by the common law that came down from semi-feudal conditions. The earlier economic conception may fairly be called static; it was concerned with possessions and estates. The newer economic conception was dynamic. It was concerned with release of productivity and exchange from a cumbrous complex of restrictions that had the force of law. The enemy was no longer the arbitrary special action of rulers. It was the whole system of common law and judicial practice in its adverse bearing upon freedom of labor, investment and exchange.

The transformation of earlier liberalism that took place because of this new interest is so tremendous that its story must be told in some detail. The concern for liberty and for the individual, which was the basis of Lockeian liberalism, persisted; otherwise the newer theory would not have been liberalism. But liberty was given a very different practical meaning. In the end, the effect was to subordinate political to economic activity; to connect natural laws with the laws of production and exchange, and to give a radically new significance to the earlier conception of reason. The name of Adam Smith is indissolubly conncected with initiation of this transformation. Although he was far from being an unqualified adherent of the idea of laissez faire, he held that the activity of individuals, freed as far as possible from political restriction, is the chief source of social welfare and the ultimate spring of social progress. He held that there is a “natural” or native tendency in every individual to better each his own estate through putting forth effort (labor) to satisfy his natural wants. Social welfare is promoted because the cumulative, but undersigned and unplanned, effect of the convergence of a multitude of individual efforts is to increase the commodities and services put at the disposal of men collectively, of society. This increase of goods and services creates new wants and leads to putting forth new modes of productive energy. There is not only a native impulse to exchange, to “truck,” but individuals are released by the processes of exchange from the necessity for labor in order to satisfy all of the individual’s own wants; through division of labor, productivity is enormously increased. Free economic processes thus bring about an endless spiral of ever increasing change, and through the guidance of an “invisible hand” (the equivalent of the doctrine of preestablished harmony so dear to the eighteenth century) the efforts of individuals for personal advancement and personal gain accrue to the benefit of society, and create a continuously closer knit interdependence of interests.

The ideas and ideals of the new political economy were congruous with the increase of industrial activity that was marked in England even before the invention of the steam engine. They spread rapidly. Their power was furthered when the great industrial and commercial expansion of England ensued in the wake of the substitution of mechanical for human energy, first in textiles and then in other occupations. Under the influence of the industrial revolution the old argument against political action as a social agency assumed a new form. Such action was not only an invasion of individual liberty but it was in effect a conspiracy against the causes that bring about social progress. The Lockeian idea of natural laws took on a much more concrete, a more directly practical, meaning. Natural law was still regarded as something more fundamental than man-made law, which by comparison is artificial. But natural laws lost their remote moral meaning. They were identified with the laws of free industrial production and free commercial exchange. Adam Smith, however, did not originate this latter idea. He took it over from the French physiocrats, who, as the name implies, believed in rule of social relations by natural law and who identified natural with economic law.

France was an agricultural country, and the economy of the physiocrats was conceived and formulated in the interest of agriculture and mining. Land, according to them, is the source of all wealth; from it comes ultimately all genuinely productive force. Industry, as distinct from agriculture, merely reshapes what nature provides. The movement was essentially a protest against governmental measures that were impoverishing the agricultural and enriched idle parasites. But its underlying philosophy was the idea that economic laws are the true natural laws while other laws are artificial and hence to be limited in scope as far as possible. In an ideal society political organization will be modeled upon the economic pattern set by nature. Ex natura, jus.

Locke had taught that labor, not land, is the source of wealth, and England was passing from an agrarian to an industrialized community. The French doctrine in its own form did not fit into the English scene. But there was no great obstacle against translating the underlying ideal of the identity of natural law with economic law into a form suited to the needs of an industrial community. The shift from land to labor (the expenditure of energy for the satisfaction of wants) required only, from the side of the philosophy of economics, that attention be centered upon human nature, rather than upon physical nature. Psychological laws, based on human nature, are as truly natural as are any laws based on land and physical nature. Land is itself productive only under the influence of the labor put forth in satisfaction of intrinsic human wants. Adam Smith was not himself especially interested in elaborating a formulation of laws in terms of human nature. But he explicitly fell back upon one natural human tendency, sympathy, to find the basis for moreals, and he used other natural impulses, the instincts to better one’s condition and to exchange, to give the foundation of economic theory. The laws of the operations of these natural tendencies, when they are freed from artificial restraints, are the natural laws governing men in their relations to one another. In individuals, the exercise of sympathy in accordance with reason (that is, in Smith’s conception, from the standpoint of an impartial spectator) is the norm of virtuous action. But government cannot appeal to sympathy. The only measures it can employ affect the motive of self-interest. It makes this appeal most effectively when it acts so as to protect individuals in the exercise of their natural self-interest. These ideas, implicit in Smith, were made explicit by his successors: in part by the classical school of economists and in part by Bentham and the Mills, father and son. For a considerable period these two schools worked hand in hand.

Economists developed the principle of the free economic activity of individuals; since this freedom was identified with absence of governmental action, conceived as an interference with natural liberty, the result was the formulation of laissez faire liberalism. Bentham carried the same conception, though from a different point of view, into a vigorous movement for reform of the common law and judicial procedure by means of legislative action. The Mills developed the psychological and logical foundation implicit in the theories of the economists and of Bentham.

I begin with Bentham. The existing legal system was intimately bound up with a political system based upon the predominance of the great landed proprietors through the rotten borough system. The operation of the new industrial forces in both production and exchange was checked and deflected at almost every point by a mass of customs that formed the core of common law. Bentham approached the situation not from the standpoint of individual liberty but from the standpoint of the effect of these restrictions upon the happiness enjoyed by individuals. Every restriction upon liberty is ipso facto a source of pain and a limitation of a pleasure that might otherwise be enjoyed. Hence the effect was the same in the two doctrines as far as the rightful province of governmental action is concerned. Bentham’s assault was aimed directly, not indirectly, like the theory of the economists, upon everything in existing law and judicial procedure that inflicted unnecessary pain and that limited the acquisition of pleasures by individuals. Moreover, his psychology converted the impulse to improve one’s condition, upon which Adam Smith had built, into the doctrine that desire for pleasure and aversion to pain are the sole forces that govern human action. The psychological theory implicit in the idea of industry and exchange controlled by desire for gain was then worked out upon the political and legal side. Moreover, the constant expansion of manufacturing and trade put the force of a powerful class interest behind the new version of liberalism. This statement does not imply that the intellectual leaders of the new liberalism were themselves moved by hope of material gain. On the contrary, they formed a group animated by a strikingly unselfish spirit, in contrast with their professed theories. Their very detachment from the immediate interests of the market place liberated them from the narrowness and shortsightedness that marked the trading class–a class that John Stuart Mill adverted to with even more bitterness than did Adam Smith. This emancipation enabled them to detect and make articulate the nascent movements of their time–a function that defines the genuine work of the intellectual class at any period. But they might have been as voices crying in the wilderness if what they taught had not coincided with the interests of a class that was constantly rising in prestige and power.

According to Bentham, the criterion of all law and of every administrative effort is its effect upon the sum of happiness enjoyed by the greatest possible number. In calculating this sum, every individual is to count as one and only as one. The mere formulation of the doctrine was an attack upon every inequality of status that had the sanction of law. In effect, it made the well-being of the individual the norm of political action in every area in which it operates. In effect, though not wholly in Bentham’s express apprehension, it transferred attention from the well-being already possessed by individuals to one they might attain if there were a radical change in social institutions. For existing institutions enabled a small number of individuals to enjoy their pleasures at the cost of the misery of a much greater number. While Bentham himself conceived that the changes to be made in legal and political institutions were mainly negative, such as abolition of abuses, corruptions and inequalities, nevertheless (as we shall see later) there was nothing in his fundamental doctrine that stood in the way of using the power of government to create, constructively and positively, new institutions if and when it should appear that the latter would contribute more effectively to the well-being of individuals.

Bentham’s best known work is entitled Principles of Morals and Legislation. In his actual treatment “morals and legislation” form a single term. It was the morals of legislation, of political action generally, with which he occupied himself, his standard being the simple one of determination of its effect upon the greatest possible happiness of the greatest possible number. He labored incessantly to expose the abuses of the existing legal system and its application in judicial procedure, civil and criminal, and in administration. He attacked these abuses, in his various works, in detail, one by one. But his attacks were cumulative in effect since he applied a single principle in his detailed criticism. He was, we may say, the first great muck-racker in the field of law. But he was more than that. Wherever he saw a defect, he proposed a remedy. He was an inventor in law and administration, as much so as any contemporary in mechanical production. He said of himself that his ambition was to “extend the experimental method of reasoning from the physical branch to the moral”–meaning, in common with English thought of the eighteenth century, by the moral the human. He also compared his own work with what physicists and chemists were doing in their fields in invention of appliances and processes that increase human welfare. That is, he did not limit his method to mere reasoning; the latter occurred only for the sake of instituting changes in actual practice. History shows no mind more fertile than his in invention of legal and administrative devices. Of him and his school, Graham Wallas said, “The fact that the fall from power of the British aristocracy in 1832 led neither to social revolution or administrative chaos at home, nor to the break up of the new British Empire abroad was largely due to the political expedients–local government reform, open competition in the civil service, scientific health and police administration, colonial self-government, Indian administrative reform–which Bentham’s disciples either found in his writings, or developed, after his death, by his methods.”2

The work of Bentham, in spite of fundamental defects in his underlying theory of human nature, is a demonstration that liberalism is not compelled by anything in its own nature to be impotent save for minor reforms. Bentham’s influence is proof that liberalism can be a power in bringing about radical social changes:–provided it combine capacity for bold and comprehensive social invention with detailed study of particulars and with courage in action. The history of the legal and administrative changes in Great Britain during the first half of the nineteenth century is chiefly the history of Bentham and his school. I think there is something significant for the liberalism of today and tomorrow to be found in the fact that his group did not consist in any large measure of politicians, legislators or public officials. On the American principle of “Let George do it, ” liberals in this country are given to supposing and hoping that some Administration when in power will take the lead in formulating and executing liberal policies. I know of nothing in history that justifies the belief and hope. A liberal program has to be developed, and in a good deal of particularity, outside of the immediate realm of governmental action and enforced upon public attention, before direct political action of a thoroughgoing liberal sort will follow. This is one lesson we have to learn from early nineteenth-century liberalism. Without a background of informed political intelligence, direct action in behalf of professed liberal ends may end in development of political irresponsibility.

Bentham’s theory led him to the view that all organized action is to be judged by its consequences, consequences that take effect in the lives of individuals. His psychology was rather rudimentary. It made him conceive of consequences as being atomic units of pleasures and pains that can be algebraically summed up. It is to this aspect of his doctrines that later writers, especially moralists, have chiefly devoted their critical attention. But this particular aspect of his theory, if we view it in the perspective of history, is an adventitious accretion. His enduring idea is that customs, institutions, law, social arrangements are to be judged on the basis of their consequences as these come home to the individuals that compose society. Because of his emphasis upon consequences, he made short work of the tenets of both of the two schools that had dominated, before his day, English political thought. He brushed aside, almost contemptuously, the conservative school that found the source of social wisdom in the customs and precedents of the past. This school has its counterpart in those empiricists of the present day who attack every measure and policy that is new and innovating on the ground that it does not have the sanction of experience, when what they really mean by “experience” is patterns of mind that were formed in a past that no longer exists.

But Bentham was equally aggressive in assault upon that aspect of earlier liberalism which was based upon the conception of inherent natural rights–following in this respect a clew given by David Hume. Natural rights and natural liberties exist only in the kingdom of mythological social zoology. Men do not obey laws because they think these laws are in accord with a scheme of natural rights. They obey because they believe, rightly or wrongly, that the consequences of obeying are upon the whole better than the consequences of disobeying. If the consequences of existing rule become too intolerable, they revolt. An enlightened self-interest will induce a ruler not to push too far the patience of subjects. The enlightened self-interest of citizens will lead them to obtain by peaceful means, as far as possible, the changes that will effect a distribution of political power and the publicity that will lead political authorities to work for rather than against the interests of the people–a situation which Bentham thought was realized by government that is representative and based upon popular suffrage. But in any case, not natural rights but consequences in the lives of individuals are the criterion and measure of policy and judgment.

Because the liberalism of the economists and the Benthamites was adapted to contemporary conditions in Great Britain, the influence of the liberalism of the school of Locke waned. By 1820 it was practically extinct. Its influence lasted much longer in the United States. We had no Bentham and it is doubtful whether he would have had much influence if he had appeared. Except for movements in codification of law, it is hard to find traces of the influence of Bentham in this country. As was intimated earlier, the philosophy of Locke bore much the same relation to the American revolt of the colonies that it had to the British revolution of almost a century earlier. Up to, say, the time of the Civil War, the United States were predominantly agrarian. As they became industrialized, the philosophy of liberty of individuals, expressed especially in freedom of contract, provided the doctrine needed by those who controlled the economic system. It was freely employed by the courts in declaring unconstitutional legislation that limited this freedom. The ideas of Locke embodied in the Declaration of Independence were congenial to our pioneer conditions that gave individuals the opportunity to carve their own careers. Political action was lightly thought of by those who lived in frontier conditions. A political career was very largely annexed as an adjunct to the action of individuals in carving their own careers. The gospel of self-help and private initiative was practiced so spontaneously that it needed no special intellectual support. Finally, there was no background of feudalism to give special leverage to the Benthamite system of legal and administrative reform.

The United States lagged more than a generation behind Great Britain in promotion of social legislation. Justice Holmes found it necessary to remind his fellow Justices that, after all, the Social Statics of Herbert Spencer had not been enacted into the American Constitution. Great Britain, largely under Benthamite influence, built up an ordered civil service independent of political party control. With us, political emoluments, like economic pecuniary rewards, went to the most enterprising competitor; to the victor belong the spoils. The principle of the greatest good to the greatest number tended to establish in Great Britain the supremacy of national over local interests. The political history of the United States is largely a record of domination by regional interests. Our fervor in law-making might be allied to Bentham’s principle of the “omnicompetence” of the legislative body. But we have never taken very seriously the laws we make, while there has been little comparable in our history to the importance attached to administration by the English utilitarian school.

I have mentioned two schools of liberalism in Great Britain, that of the economists and of the utilitarians. At first they walked the same path. The later history of liberalism in that country is largely a matter of a growing divergence, and finally of an open split. While Bentham personally was on the side of the classical economists, his principle of judgment by consequences lends itself to opposite application. Bentham himself urged a great extension of public education and of action in behalf of public health. When he disallowed the doctrine of inalienable individual natural rights, he removed, as far as theory is concerned, the obstacle to positive action by the state whenever it can be shown that the general well-being will be promoted by such action. Dicey in his Law and Opinion in England has shown that collectivist legislative policies gained in force for at least a generation after the sixties. It was stimulated, naturally, by the reform bills that greatly broadened the basis of suffrage. The use of scientific method, even if sporadic and feeble, encouraged study of actual consequences and promoted the formation of legislative policies designed to improve the consequences brought about by existing institutions. At all events, in connection with Benthamite influence, it greatly weakened the notion that Reason is a remote majestic power that discloses ultimate truths. It tended to render it an agency in investigation of concrete situations and in projection of measures for their betterment.

I would not, however, give the impression that the trend away from individualistic to collectivistic liberalism was the direct effect of utilitarianism. On the contrary, social legislation was fostered primarily by Tories, who, traditionally, had no love for the industrialist class. Benthamite liberalism was not the source of factory laws, laws for the protection of child and women, prevention of their labor in mines, workmen’s compensation acts, employers’ liability laws, reduction of hours of labor, the dole, and a labor code. All of these measures went contrary to the idea of liberty of contract fostered by laissez faire liberalism. Humanitarianism, in alliance with evangelical piety and with romanticism, gave chief support, from the intellectual and emotional side, to these measures, as the Tory party was their chief political agent. No account of the rise of humanitarian sentiment as a force in creation of the new regulations of industry would be adequate that did not include the names of religious leaders drawn from both dissenters and the Established Church. Such names as Wilberforce, Clarkson, Zachary Macaulay, Elizabeth Fry, Hannah More, as well as Lord Shaftesbury, come to mind. The trades unions were gaining power and there was an active socialist movement, as represented by Robert Owen. But in spite of, or along with, such movements, we have to remember that liberalism is associated with generosity of outlook as well as with liberty of belief and action. Gradually a change came over the spirit and meaning of liberalism. It came surely, if gradually, to be disassociated from the laissez faire creed and to be associated with the use of governmental action for aid to those at economic disadvantage and for alleviation of their conditions. In this country, save for a small band of adherents to earlier liberalism, ideas and policies of this general type have virtually come to define the meaning of liberal faith. American liberalism as illustrated in the political progressivism of the early present century has so little in common with British liberalism of the first part of the last century that it stands in opposition to it.

The influence of romanticism, as exemplified in different ways by Coleridge, Wordsworth, Carlyle and Ruskin, is worthy of especial note. These men were politically allied as a rule with the Tory party, if not actively, at least in sympathy. The romanticists were all of them vigorous opponents of the consequences of the industrialization of England, and directed their assaults as the economists and Benthamites whom they held largely responsible for these consequences. As against dependence upon uncoordinated individual activities, Coleridge emphasized the significance of enduring institutions. They, according to him, are the means by which men are held together in concord of mind and purpose, the only real social bond. They are the force by which human relations are kept from disintegrating into an aggregate of unconnected and conflicting atoms. His work and that of his followers was a powerful counterpoise to the anti-historic quality of the Benthamite school. The leading scientific interest of the nineteenth century came to be history, including evolution within the scope of history. Coleridge was no historian; he had no great interest in historical facts. But his sense of the mission of great historic institutions was profound. Wordsworth preached the gospel of return to nature, of nature expressed in rivers, dales and mountains and in the souls of simple folk. Implicitly and often explicitly he attacked industrialization as the great foe of nature, without and within. Carlyle carried on a constant battle against utilitarianism and the existing socio-economic order, which he summed up in a single phrase as “anarchy plus a constable.” He called for a regime of social authority to enforce social ties. Ruskin preached the social importance of art and joined to it a denunciation of the entire reigning system of economics, theoretical and practical. The esthetic socialists of the school of William Morris carried his teachings home to the popular mind.

The romantic movement profoundly affected some who had grown up in the straitest sect of laissez faire liberalism. The intellectual career of John Stuart Mill was a valiant if unsuccessful struggle to reconcile the doctrines he derived, almost in infancy, from his father with a feeling of their hollowness when compared with the values of poetry, of enduring historic institutions, and of the inner life, as portrayed by the romanticists. He was keenly sensitive to the brutality of life about him and its low intellectual level, and saw the relation between these two traits. At one time, he even went so far as to say that he looked forward to the coming of an age “when the division of the produce of labour? will be made by concert on an acknowledged principle of justice.” He asserted that existing institutions were merely provisional, and that the “laws” governing the distribution of wealth are not social but of man?s contrivance and are man?s to change. A long distance lies between the philosophy embodied in such sayings and his earlier assertion that “the sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the freedom of action of any person is self?protection.” The romantic school was the chief influence in effecting the change.

There was in addition another intellectual force at work in changing the earlier liberalism, which openly professed liberal aims while at the same time attacking earlier liberalism. The name of Thomas Hill Green is not widely known outside of technical philosophical circles. But he was the leader in introducing into England, in coherent formulation, the organic idealism that originated in Germany?and that originated there largely in reaction against the basic philosophy of individualistic liberalism and individualist empiricism. John Mill himself was greatly troubled by the consequences that followed from the psychological doctrine of associationalism. Mental bonds in belief and purpose which are the product of external associations can easily be broken when circumstances change. The moral and social consequence is a threatened destruction of all stable bases of belief and social relationship. Green and his followers exposed this weakness in all phases of the atomistic philosophy that had developed under the alleged empiricism of the earlier liberal school. They criticized piece by piece almost every item of the theory of mind, knowledge and society that had grown out of the teachings of Locke. They asserted that relations constitute the reality of nature, of mind and of society. But Green and his followers remained faithful, as the romantic school did not, to the ideals of liberalism; the conceptions of a common good as the measure of political organization and policy, of liberty as the most precious trait and very seal of individuality, of the claim of every individual to the full development of his capacities. They strove to provide unshakeable objective foundations in the very structure of things for these moral claims, instead of basing them upon the sandy ground of the feelings of isolated human beings. For the relations that constitute the essential nature of things are, according to them, the expression of an objective Reason and Spirit that sustains nature and the human mind.

The idealistic philosophy taught that men are held together by the relations that proceed from and that manifest an ultimate cosmic mind. It followed that the basis of society and the state is shared intelligence and purpose, not force nor yet self-interest. The state is a moral organism, of which government is one organ. Only by participating in the common purpose as it works for the common good can individual human beings realize their true individualities and become truly free. The state is but one organ among many of the Spirit and Will that holds all things together and that makes human beings members of one another. It does not originate the moral claim of individuals to the full realization of their potentialities as vehicles of objective thought and purpose. Moreover, the motives it can directly appeal to are not of the highest kind. But it is the business of the state to protect all forms and to promote all modes of human association in which the moral claims of the members of society are embodied and which serve as the means of voluntary self-realization. Its business is negatively to remove the obstacles that stand in the way of individuals coming to consciousness of themselves for what they are, and positively to promote the cause of public education. Unless the state does this work it is no state. These philosophical liberals pointed out the restrictions, economic and political, which prevent many, probably majority, of individuals from the voluntary intelligent action by which they may become what they are capable of becoming. The teachings of this new liberal school affected the thoughts and actions of multitudes who did not trouble themselves to understand the philosophical doctrine that underlay it. They served to break down the idea that freedom is something that individuals have as a ready-made possession, and to instill the idea that it is something to be achieved, while the possibility of the achievement was shown to be conditioned by the institutional medium in which an individual lives. These new liberals fostered the idea that the state has the responsibility for creating institutions under which individuals can effectively realize the potentialities that are theirs.

Thus from various sources and under various influences there developed an inner split in liberalism. This cleft is one cause of the ambiguity from which liberalism still suffers and which explains a growing impotency. These are still those who call themselves liberals who define liberalism in terms of the old opposition between the province of organized social action and the province of purely individual initiative and effort. In the name of liberalism they are jealous of every extension of governmental activity. They may grudgingly concede the need of special measures of protection and alleviation undertaken by the state at times of great social stress, but they are the confirmed enemies of social legislation (even prohibition of child labor), as standing measures of political policy. Wittingly or unwittingly, they still provide the intellectual system of apologetics for the existing economic regime, which they strangely, it would seem ironically, uphold as a regime of individual liberty for all.

But the majority who call themselves liberals today are committed to the principle that organized society must use its powers to establish the conditions under which the mass of individuals can possess actual as distinct from merely legal liberty. They define their liberalism in the concrete in terms of a program of measures moving toward this end. They believe that the conception of the state which limits the activities of the latter to keeping order as between individuals and to securing redress for one person when another person infringes the liberty existing law has given him, is in effect simply a justification of the brutalities and inequities of the existing order. Because of this internal division within liberalism its later history is wavering and confused. The inheritance of the past still causes many liberals, who believe in a generous use of the powers of organized society to change the terms on which human beings associate together, to stop short with merely protective and alleviatory measures–a fact that partly explains why another school always refers to “reform” with scorn. It will be the object of the next chapter to portray the crisis in liberalism, the impasse in which it now almost finds itself, and through criticism of the deficiencies of earlier liberalism to suggest the way in which liberalism may resolve the crisis, and emerge as a compact, aggressive force.

The Crisis in LiberalismThe net effect of the struggle of early liberals to emancipate individuals from restriction imposed upon them by the inherited type of social organization was to pose a problem, that of a new social organization. The ideas of liberals set forth in the first third of the nineteenth century were potent in criticism and in analysis. They released forces that had been held in check. But analysis is not construction, and release of force does not of itself give direction to the force that is set free. Victorian optimism concealed for a time the crisis at which liberalism had arrived. But when that optimism vanished amid the conflict of nations, classes and races characteristic of the latter part of the nineteenth century–a conflict that has grown more intense with the passing years–the crisis could no longer be covered up. The beliefs and methods of earlier liberalism were ineffective when faced with the problems of social organization and integration. Their inadequacy is a large part of belief now so current that all liberalism is an outmoded doctrine. At the same time, insecurity and uncertainty in belief and purpose are powerful factors in generating dogmatic faiths that are profoundly hostile to everything to which liberalism in any possible formulation is devoted.

In a longer treatment, the crisis could be depicted in terms of the career of John Stuart Mill, during a period when the full force of the crisis was not yet clearly manifest. He records in his Autobiography that, as early as 1826, he asked himself this question: “Suppose that all your objects in life were realized: that all the changes in institutions and opinions which you are looking forward to, could be completely effected at this very instant: would this be a great joy and happiness to you?” His answer was negative. The struggle for liberation had given him the satisfaction that comes from active struggle. But the prospect of the goal attained presented him with a scene in which something unqualifiedly necessary for the good life was lacking. He found something profoundly empty in the spectacle he imaginatively faced. Doubtless physical causes had something to do with his growing doubt as to whether life would be worth living were the goal of his ambitions realized; sensitive youth often undergoes such crises. But he also felt that there was something inherently superficial in the philosophy of Bentham and his father. This philosophy now seemed to him to touch only the externals of life, but not its inner springs of personal sustenance and growth. I think it a fair paraphrase to say that he found himself faced with only intellectual abstractions. Criticism has made us familiar with the abstraction known as the economic man. The utilitarians added the abstraction of the legal and political ma. But somehow they had failed to touch man himself. Mill first found relief in the fine arts, especially poetry, as a medium for the cultivation of the feelings, and reacted against Benthamism as exclusively intellectualistic, a theory that identified man with a reckoning machine. Then under the influence of Coleridge and his disciples he learned that institutions and traditions are indispensable to the nurture of what is deepest and most worthy in human life. Acquaintance with Comte’s philosophy of a future society based on the organization of science gave him a new end for which to strive, the institution of a kind of social organization in which there should be some central spiritual authority.

The life-long struggle of Mill to reconcile these ideas with those which were deeply graven in his being by his earlier Benthamism concern us here only as a symbol of the enduring crisis of belief and action brought about in liberalism itself when the need arose for uniting earlier ideas of freedom with an insistent demand for social organization, that is, for constructive synthesis in the realm of thought and social institutions. The problem of achieving freedom was immeasurably widened and deepened. It did not now present itself as a conflict between government and the liberty of individuals in matters of conscience and economic action, but as a problem of establishing an entire social order, possessed of a spiritual authority that would nurture and direct the inner as well as the outer life of individuals. The problem of science was no longer merely technological applications for increase of material productivity, but imbuing the minds of individuals with the spirit of reasonableness, fostered by social organization and contributing to its development. The problem of democracy was seen to be not solved, hardly more than externally touched, by the establishment of universal suffrage and representative government. As Havelock Ellis has said, “We see now that the vote and the ballot-box do not make the voter free from even external pressure; and, which is of much more consequence, they do not necessarily free him from his own slavish instincts.” The problem of democracy becomes the problem of that form of social organization, extending to all the areas and ways of living, in which the powers of individuals shall not be merely released from mechanical external constraint but shall be fed, sustained and directed. Such an organization demands much more of education than general school, which without a renewal of the springs of purpose and desire becomes a new mode of mechanization and formalization, as hostile to liberty as ever was governmental constraint. It demands of science much more than external technical application–which again leads to mechanization of life and results in a new kind of enslavement. It demands that the method of inquiry, of discrimination, of test by verifiable consequences, be naturalized in all the matters, of large and of detailed scope, that arise for judgment.

The demand for a form of social organization that should include economic activities but yet should convert them into servants of the development of the higher capacities of individuals, is one that earlier liberalism did not meet. If we strip its creed from adventitious elements, there are, however, enduring values for which earlier liberalism stood. These values are liberty, the development of the inherent capacities of individuals made possible through liberty, and the central role of free intelligence in inquiry, discussion and expression. But elements that were adventitious to these values colored every one of these ideals in ways that rendered them either impotent or perverse when the new problem of social organization arose.

Before considering the three values, it is advisable to note one adventitious idea that played a large role in the later incapacitation of liberalism. The earlier liberals lacked historic sense and interest. For a while this lack had an immediate pragmatic value. It gave liberals a powerful weapon in their fight with reactionaries. For it enabled them to undercut the appeal to origin, precedent and past history by which the opponents of social change gave sacrosanct quality to existing inequities and abuses. But disregard of history took its revenge. It blinded the eyes of liberals to the fact that their own special interpretations of liberty, individuality and intelligence were themselves historically conditioned, and were relevant only to their own time. They put forward their ideas as immutable truths good at all times and places; they had no idea of historic relativity, either in general or in its application to themselves.

When their ideas and plans were projected they were an attack upon the interests that were vested in established institutions and that had the sanction of custom. The new forces for which liberals sought an entrance were incipient; the status quo was arrayed against their release. By the middle of the nineteenth century the contemporary scene had radically altered. The economic and political changes for which they strove were so largely accomplished that they had become in turn the vested interest, and their doctrines, especially in the form of laissez faire liberalism, now provided the intellectual justification of the status quo. This creed is still powerful in this country. The earlier doctrine of “natural rights,” superior to legislative action, has been given a definitely economic meaning by the courts, and used by judges to destroy social legislation passed in the interest of a real, instead of purely formal, liberty of contract. Under the caption of “rugged individualism” it inveighs against all new social policies. Beneficiaries of the established economic regime band themselves together in what they call Liberty Leagues to perpetuate the harsh regimentation of millions of their fellows. I do not imply that resistance to change would not have appeared if it had not been for the doctrines of earlier liberals. But had the early liberals appreciated the historic relativity of their own interpretation of the meaning of liberty, the later resistance would certainly have been deprived of its chief intellectual and moral support. The tragedy is that although these liberals were the sworn foes of political absolutism, they were themselves absolutists in the social creed they formulated.

This statement does not mean, of course, that they were opposed to social change; the opposite is evidently the case. But it does mean they held that beneficial social change can come about in but one way, the way of private economic enterprise, socially undirected, based upon and resulting in the sanctity of private property–that is to say, freedom from social control. So today those who profess the earlier type of liberalism ascribe to this one factor all social betterment that has occurred; such as the increase in productivity and improved standards of living. The liberals did not try to prevent change, but they did try to limit its course to a single channel and to immobilize the channel.

If the early liberals had put forth their special interpretation of liberty as something subject to historic relativity they would not have frozen it into a doctrine to be applied at all times under all social circumstances. Specifically, they would have recognized that effective liberty is a function of the social conditions existing at any time. If they had done this, they would have known that as economic relations became dominantly controlling forces in setting the pattern of human relations, the necessity of liberty for individuals which they proclaimed will require social control of economic forces in the interest of the great mass of individuals. Because the liberals failed to make a distinction between purely formal or legal liberty and effective liberty of thought and action, the history of the last one hundred years is the history of non-fulfillment of their predictions. It was prophesied that a regime of economic liberty would bring about interdependence among nations and consequently peace. The actual scene has been marked by wars of increasing scope and destructiveness. Even Karl Marx shared the idea that the new economic forces would destroy economic nationalism and usher in an era of internationalism. The display of exacerbated nationalism now characterizing the world is a sufficient comment. Struggle for raw materials and markets in backward countries, combined with foreign financial control of their domestic industrial development, has been accompanied by all kinds of devices to prevent access of other advanced nations to the national market-place.

The basic doctrine of early economic liberals was that the regime of economic liberty as they conceived it, would almost automatically direct production through competition into channels that would provide, as effectively as possible, socially needed commodities and services. Desire for personal gain early learned that it could better further the satisfaction of that desire by stifling competition and substituting great combinations of non-competing capital. The liberals supposed the motive of individual self-interest would so release productive energies as to produce ever-increasing abundance. They overlooked the fact that in many cases personal profit can be better served by maintaining artificial scarcity and by what Veblen called systematic sabotage of production. Above all, in identifying the extension of liberty in all of its modes with extension of their particular brand of economic liberty, they completely failed to anticipate the bearing of private control of the means of production and distribution upon the effective liberty of the masses in industry as well as in cultural goods. An era of power possessed by the few took the place of the era of liberty for all envisaged by the liberals of the early nineteenth century.

These statements do not imply that these liberals should or could have foreseen the changes that would occur, due to the impact of new forces of production. The point is that their failure to grasp the historic position of the interpretation of liberty they put forth served later to solidify a social regime that was a chief obstacle to attainment of the ends they professed. One aspect of this failure is worth especial mention. No one has ever seen more clearly then the Benthamites that the political self-interest of rulers, if not socially checked and controlled, leads to actions that destroy liberty for the mass of people. Their perception of this fact was a chief ground for their advocacy of representative government, for they saw in this measure a means by which the self-interest of the rulers would be forced into conformity with the interests of their subjects. But they had no glimpse of the fact that private control of the new forces of production, forces which affect the life of every one, would operate in the same way as private unchecked control of political liberty. But they failed to perceive that social control of economic forces is equally necessary if anything approaching economic equality and liberty is to be realized.

Bentham did believe that increasing equalization of economic fortunes was desirable. He justified his opinion of its desirability on the ground of the greater happiness of the greater number: to put the matter crudely, the possession of ten thousand dollars by a thousand persons would generate a greater sum of happiness than the possession of ten million dollars by one person. But he believed that the regime of economic liberty would of itself tend in the direction of greater equalization. Meantime, he held that “time is the only mediator,” and he opposed the use of organized social power to promote equalization on the ground that such action would disturb the “security” that is even a great condition of happiness than is equality.

When it became evident that disparity, not equality, was the actual consequence of laissez faire liberalism, defenders of the latter developed a double system of justifying apologetics. Upon one front, they fell back upon the natural inequalities of individuals in psychological and moral make-up, asserting that inequality of fortune and economic status is the “natural” and justifiable consequence of the free play of these inherent differences. Herbert Spencer even erected this idea into a principle of cosmic justice, based upon the idea of the proportionate relation existing between cause and effect. I fancy that today there are but few who are hardy enough, even admitting the principle of natural inequalities, to assert that the disparities of property and income bear any commensurate ratio to inequalities in the native constitution of individuals. If we suppose that there is in fact such a ratio, the consequences are so intolerable that the practical inference to be drawn is that organized social effort should intervene to prevent the alleged natural law from taking full effect.

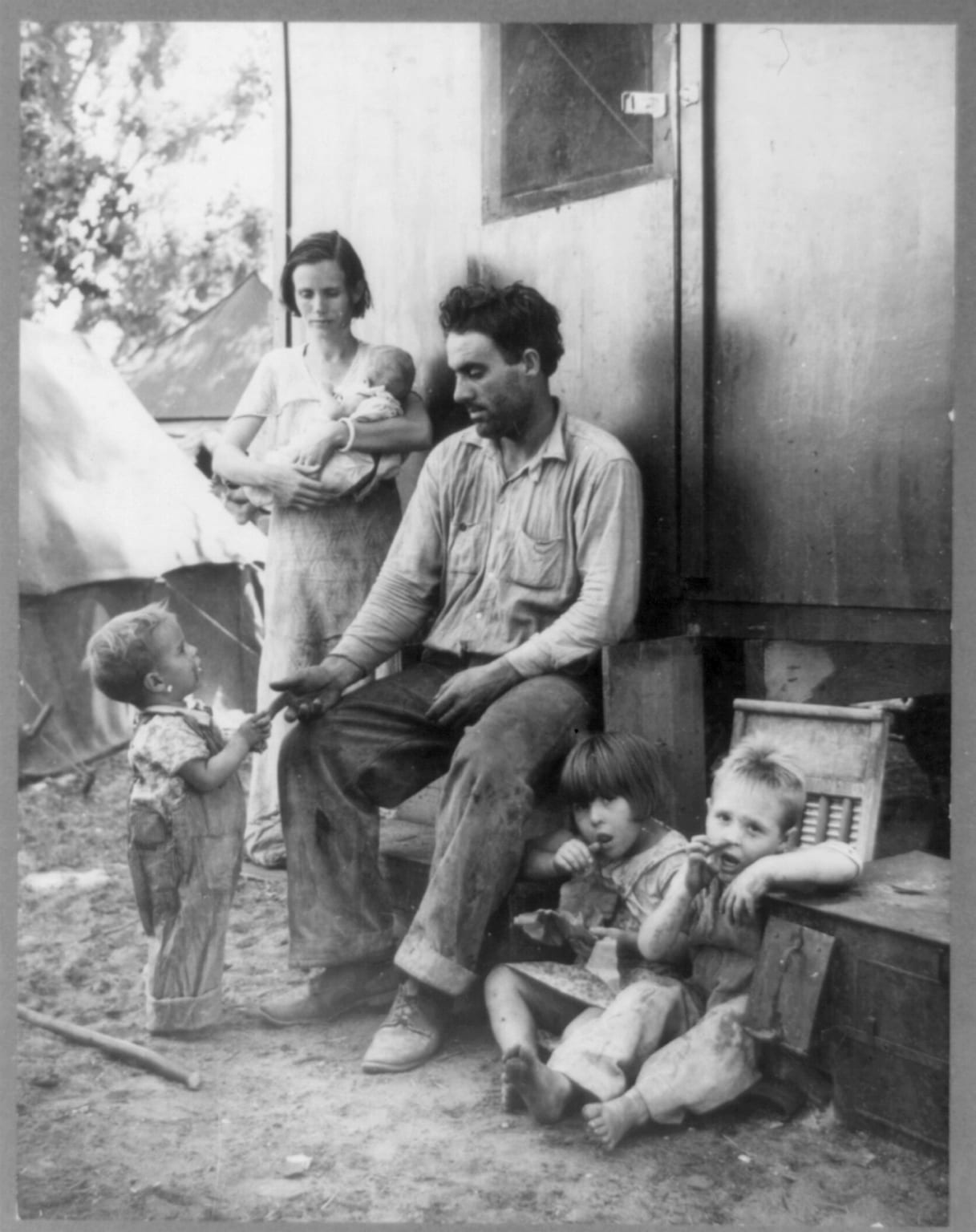

The other line of defense is unceasing glorification of the virtues of initiative, independence, choice and responsibility, virtues that centre in and proceed from individuals as such. I am one who believes that we need more, not fewer, “rugged individuals” and it is in the name of rugged individualism that I challenge the argument. Instead of independence, there exists parasitical dependence on a wide scale-witness the present need for the exercise of charity, private and public, on a vast scale. The current argument against the public dole on the ground that it pauperizes and demoralizes those who receive it has an ironical sound when it comes from those who would leave intact the conditions that cause the necessity for recourse to the method of support of millions at public expense. Servility and regimentation are the result of control by the few of access to means of productive labor on the part of the many. An even more serious objection to the argument is that it conceives of initiative, vigor, independence exclusively in terms of their least significant manifestation. They are limited to exercise in the economic area. The meaning of their exercise in connection with the cultural resources of civilization, in such matters as companionship, science and art, is all but ignored. It is at this last point in particular that the crisis of liberalism and the need for a reconsideration of it in terms of the genuine liberation of individuals are most evident. The enormous exaggeration of material and materialistic economics that now prevails at the expense of cultural values, is not itself the result of earlier liberalism. But, as was illustrated in the personal crisis through which Mill passed, it is an exaggeration which is favored, both intellectually and morally, by fixation of the early creed.

This fact induces a natural transition from the concept of liberty to that of the individual. The underlying philosophy and psychology of earlier liberalism led to a conception of individuality as something ready-made, already possessed, and needing only the removal of certain legal restrictions to come into full play. It was not conceived as a moving thing, something that is attained only by continuous growth. Because of this failure, the dependence in fact of individuals upon social conditions was made little of. It is true that some of the early liberals, like John Stuart Mill, made much of the effect of “circumstances” in producing differences among individuals. But the use of the word and idea of “circumstances” is significant. It suggests–and the context bears out the suggestion–that social arrangements and institutions were thought of as things that operate from without, not entering in any significant way into the internal make-up and growth of individuals. Social arrangements were treated not as positive forces but as external limitations. Some passages in Mill’s discussion of the logic of the social sciences are pertinent. “Men in a state of society are still men; their actions and passions are obedient to the laws of individual human nature. Men are not, when brought together, converted into a different kind of substance, as hydrogen and oxygen differ from water–Human beings in society have no properties but those which are derived from, and may be resolved into, the laws of individual men.” And again he says: “The actions and feelings of men in the social state are entirely governed by psychological laws.”3

There is an implication in these passages that liberals will be the last to deny. This implication is directly in line with Mill’s own revolt against the creed in which he was educated. As far as the statements are a warning against attaching undue importance to merely external institutional changes, to changes that do not enter into the desires, purposes and beliefs of the very constitution of individuals, they express an idea to which liberalism is committed by its own nature. But Mill means something at once less and more than this. While he would probably have denied that he held to the notion of a state of nature in which individuals exist prior to entering into a social state, he is in fact giving a psychological version of that doctrine. Individuals, it is implied, have a full-blown psychological and moral nature, having its own set laws, independently of their association with one another. It is the psychological laws of this isolated human nature from which social laws are derived and into which they may be resolved. His own illustration of water in its difference from hydrogen and oxygen on separation might have taught him better, if it had not been for the influence of a prior dogma. That the human infant is modified in mind and character by his connection with others in family life and that the modification continues throughout life as his connections with others broaden, is as true as that hydrogen is modified when it combines with oxygen. If we generalize the meaning of this fact, it is evident that while there are native organic or biological structures that remain fairly constant, the actual “laws” of human nature are laws of individuals in association, not of beings in a mythical condition apart from association. In other words, liberalism that takes its profession of the importance of individuality with sincerity must be deeply concerned about the structure of human association. For the latter operates to affect negatively and positively, the development of individuals. Because a wholly unjustified idea of opposition between individuals and society has become current, and because its currency has been furthered by the underlying philosophy of individualistic liberalism, there are many who in fact are working for social changes such that rugged individuals may exist in reality, that have become contemptuous of the very idea of individuality, while others support in the name of individualism institutions that militate powerfully against the emergence and growth of beings possessed of genuine individuality.

It remains to say something of the third enduring value in the liberal creed:–Intelligence. Grateful recognition is due early liberals for their valiant battle in behalf of freedom of thought, conscience, expression and communication. The civil liberties we possess, however precariously today, are in large measure the fruit of their efforts and those of the French liberals who engaged in the same battle. But their basic theory as to the nature of intelligence is such as to offer no sure foundation for the permanent victory of the cause they espoused. They resolved mind into a complex of external associations among atomic elements, just as they resolved society itself into a similar compound of external associations among individuals, each of whom has his own independently fixed nature. Their psychology was not in fact the product of impartial inquiry into human nature. It was rather a political weapon devised in the interest of breaking down the rigidity of dogmas and of institutions that had lost their relevancy. Mill’s own contention that psychological laws of the kind he laid down were prior to the laws of men living and communicating together, acting and reacting upon one another, was itself a political instrument forged in the interest of criticism of beliefs and institutions that he believed should be displaced. The doctrine was potent in exposure of abuses; it was weak for constructive purposes. Bentham’s assertion that he introduced the method of experiment into the social sciences held good as far as resolution into atoms acting externally upon one another, after the Newtonian model, was concerned. It did not recognize the place in experiment of comprehensive social ideas as working hypotheses in direction of action.

The practical consequence was also the logical one. When conditions had changed and the problem was one of constructing social organization from individual units that had been released from old social ties, liberalism fell upon evil times. The conception of intelligence as something that arose from the association of isolated elements, sensations and feelings, left no room for far-reaching experiments in construction of a new social order. It was definitely hostile to everything like collective social planning. The doctrine of laissez faire was applied to intelligence as well as to economic action, although the conception of experimental method in science demands a control by comprehensive ideas, projected in possibilities to be realized by action. Scientific method is as much opposed to go-as-you-please in intellectual matters as it is to reliance upon habits of mind whose sanction is that they were formed by “experience” in the past. The theory of mind held by the early liberals advanced beyond dependence upon the past but it did not arrive at the idea of experimental and constructive intelligence.

The dissolving atomistic individualism of the liberal school evoked by way of reaction the theory of organic objective mind. But the effect of the latter theory embodied in idealistic metaphysics was also hostile to intentional social planning. The historical march of mind, embodied in institutions, was believed to account for social changes–all in its own good time. A similar conception was fortified by the interest in history and in evolution so characteristic of the later nineteenth century. The materialistic philosophy of Spencer joined hands with the idealistic doctrine of Hegel in throwing the burden of social direction upon powers that are beyond deliberate social foresight and planning. The economic dialectic of ideas, as interpreted by the social-democratic party in Europe, was taken to signify an equally inevitable movement toward a predestined goal. Moreover, the idealistic theory of objective spirit provided an intellectual justification for the nationalisms that were rising. Concrete manifestation of absolute mind was said to be provided through national states. Today, this philosophy is readily turned to the support of the totalitarian state.

The crisis in liberalism is connected with failure to develop and lay hold of an adequate conception of intelligence integrated with social movements and a factor in giving them direction. We cannot mete out harsh blame to the early liberals for failure to attain such a conception. The first scientific society for the study of anthropology was founded the year in which Darwin’s Origin of Species saw the light of day. I cite this particular fact to typify the larger fact that the sciences of society, the controlled study of man in his relationships, are the product of the later nineteenth century. Moreover, these disciplines not only came into being too late to influence the formulation of liberal social theory, but they themselves were so much under the influence of the more advanced physical sciences that it was supposed that their findings were of merely theoretic import. By this statement, I mean that although the conclusions of the social disciplines were about man, they were treated as if they were of the same nature as the conclusions of physical science about remote galaxies of stars. Social and historical inquiry is in fact a part of the social process itself, not something outside of it. The consequence of not perceiving this fact was that the conclusions of the social sciences were not made (and still are not made in any large measure) integral members of a program of social action. When the conclusions of inquiries that deal with man are left outside the program of social action, social policies are necessarily left without the guidance that knowledge of man can provide, and that it must provide if social action is not to be directed either by mere precedent and custom or else by the happy intuitions of individual minds. The social conception of the nature and work of intelligence is still immature; in consequence, its use as a director of social action is inchoate and sporadic. It is the tragedy of earlier liberalism that just at the time when the problem of social organization was most urgent, liberals could bring to us solution nothing but the conception that intelligence is an individual possession.

It is all but a commonplace that today physical knowledge and its technical applications have far outrun our knowledge of man and its application in social invention and engineering. What I have just said indicates a deep source of the trouble. After all, our accumulated knowledge of man and his ways, furnished by anthropology, history, sociology and psychology, is vast, even thought it be sparse in comparison with our knowledge of physical nature. But it is still treated as so much merely theoretic knowledge amassed by specialists, and at most communicated by them in books and articles to the general public. We are habituated to the idea that every discovery in physical knowledge signifies, sooner or later, a change in the processes of production; there are countless persons whose business it is to see that these discoveries take effect through invention in improved operations in practice. There is next to nothing of the same sort with respect to knowledge of man and human affairs. Although the latter is recognized to concern man in the sense of being about him, it is of less practical effect than are the much more remote findings of physical science.

The inchoate state of social knowledge is reflected in the two fields where intelligence might be supposed to be most alert and most continuously active, education and the formation of social policies in legislation. Science is taught in our schools. But very largely it appears in schools simply as another study, to be acquired by much the same methods as are employed in “learning” the older studies that are part of the curriculum. If it were treated as what it is, the method of intelligence itself in action, then the method of science would be incarnate in every branch of study and every detail of learning. Thought would be connected with the possibility of action, and every mode of action would be reviewed to see its bearing upon the habits and ideas from which it sprang. Until science is treated educationally in this way, the introduction of what is called science into the schools signifies one more opportunity for the mechanization of the material and methods of study. When “learning” is treated not as an expansion of the understanding and judgment of meanings but as an acquisition of information, the method of cooperative experimental intelligence finds its way into the working structure of the individual only incidentally and by devious paths.

Of the place and use of socially organized intelligence in the conduct of public affairs, through legislation and administration, I shall have something to say in the next chapter. At this point of the discussion I am content to ask the reader to compare the force it now exerts in politics with that of the interest of individuals and parties in capturing and retaining office and power, with that exercised by the propaganda of publicity agents and that of organized pressure groups.

Humanly speaking, the crisis in liberalism was a product of particular historical events. Soon after liberal tenets were formulated as eternal truths, it became an instrument of vested interests in opposition to further social change, a ritual of lip-service, or else was shattered by new forces that came in. Nevertheless, the ideas of liberty, of individuality and of freed intelligence have an enduring value, a value never more needed than now. It is the business of liberalism to state these values in ways, intellectual and practical, that are relevant to present needs and forces. If we employ the conception of historic relativity, nothing is clearer than that the conception of historic relativity, nothing is clearer than that the conception of liberty is always relative to forces that at a given time and place are increasingly felt to be oppressive. Liberty in the concrete signifies release from the impact of particular oppressive forces; emancipation from something once taken as a normal part of human life but now experienced as bondage. At one time, liberty signified liberation from chattel slavery; at another time, release of a class from serfdom. During the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries it meant liberation from despotic dynastic rule. A century later it meant release of industrialists from inherited legal customs that hampered the rise of new forces of production. Today, it signifies liberation from material insecurity and from the coercions and repressions that prevent multitudes from participation in the vast cultural resources that are at hand. The direct impact of liberty always has to do with some class or group that is suffering in a special way from some form of constraint exercised by the distribution of powers that exists in contemporary society. Should a classless society ever come into being the formal concept of liberty would lose its significance, because the fact for which it stands would have become an integral part of the established relations of human beings to one another.

Until such a time arrives liberalism will continue to have a necessary social office to perform. Its task is the mediation of social transitions. This phrase may seem to some to be a virtual admission that liberalism is a colorless “middle of the road” doctrine. Not so, even though liberalism has sometimes taken that form in practice. We are always dependent upon the experience that has accumulated in the past and yet there are always new forces are to operate and the new needs to be satisfied, a reconstruction of the patterns of old experience. The old and the new have forever to be integrated with each other, so that the values of old experience may become the servants and instruments of new desires and aims. We are always possessed by habits and customs, and this fact signifies that we are always influenced by the inertia and the momentum of forces temporally outgrown but nevertheless still present with us as a part of our being. Human life gets set in patterns, institutional and moral. But change is also with us and demands the constant remaking of old habits and old ways of thinking, desiring and acting. The effective ration between the old and the stabilizing and the new and disturbing is very different at different times. Sometimes whole communities seem to be dominated by custom, and changes are produced only by irruptions and invasions from outside. Sometimes, as a present, change is so varied and accelerated that customs seem to be dissolving before our very eyes. But be the ratio little or great, there is always an adjustment to be made, and as soon as the need for it becomes conscious, liberalism has a function and a meaning. It is not that liberalism creates the need, but that the necessity for adjustment defines the office of liberalism.

For the only adjustment that does not have to be made over again, and perhaps even under more unfavorable circumstances than when it was first attempted, is that effected through intelligence as a method. In its large sense, this remaking of the old through union with the new is precisely what intelligence is. It is conversion of past experience into knowledge and projection of that knowledge in ideas and purposes that anticipate what may come to be in the future and that indicate how to realize what is desired. Every problem that arises, personal or collective, simple or complex, is solved only by selecting material from the store of knowledge amasses in past experience and by bringing into play habits already formed. But the knowledge and the habits have to be modified to meet the new conditions that have arisen. In collective problems, the habits that are involved are traditions and institutions. The standing danger is either that they will be acted upon implicitly, without reconstruction to meet new conditions, or else that there will be an impatient and blind rush forward, directed only by some dogma rigidly adhered to. The office of intelligence in every problem that either a person or a community meets is to effect a working connection between old habits, customs, institutions, beliefs, and new conditions. What I have called the mediating function of liberalism is all one with the work of intelligence. This fact is the root, whether it be consciously realized or not, of the emphasis placed by liberalism upon the role of freed intelligence as the method of directing social action.