Introduction

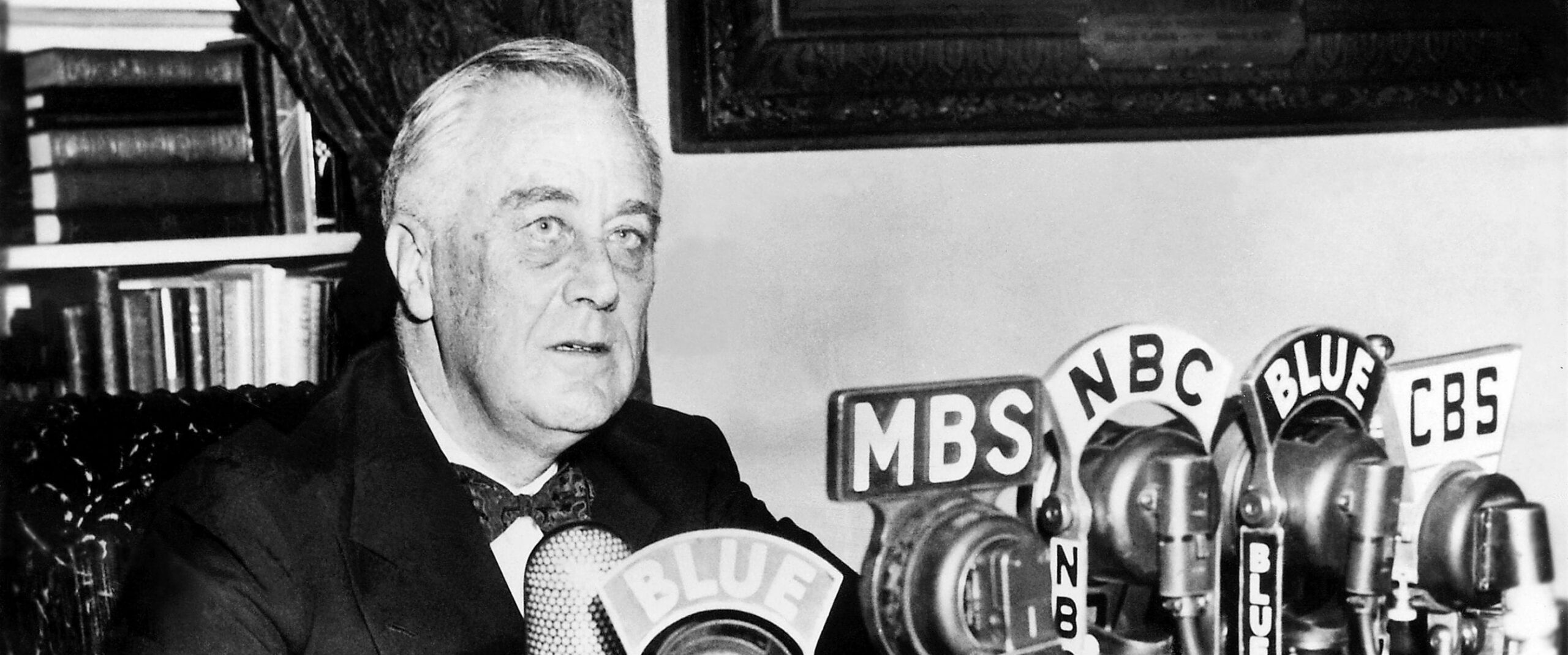

Roosevelt believed that the success of his administration depended upon his ability to maintain a favorable dialogue with the American people. To that end, Roosevelt sought out innovative ways of shaping American public opinion in order to generate broad public support for his programs. One such innovation was the use of “fireside chats,” a series of thirty evening radio addresses between 1933 and 1944. He used these addresses to explain his policies, respond to criticism, silence rumor mongering, and bond with the American people. These chats redefined the relationship between the office and the electorate: his warm manner made people feel closer to the president and reassured by his plans to combat the various crises facing the nation. Although the chats were extremely popular, Roosevelt resisted calls to deliver more such chats for fear that too many would dilute their impact on the American public.

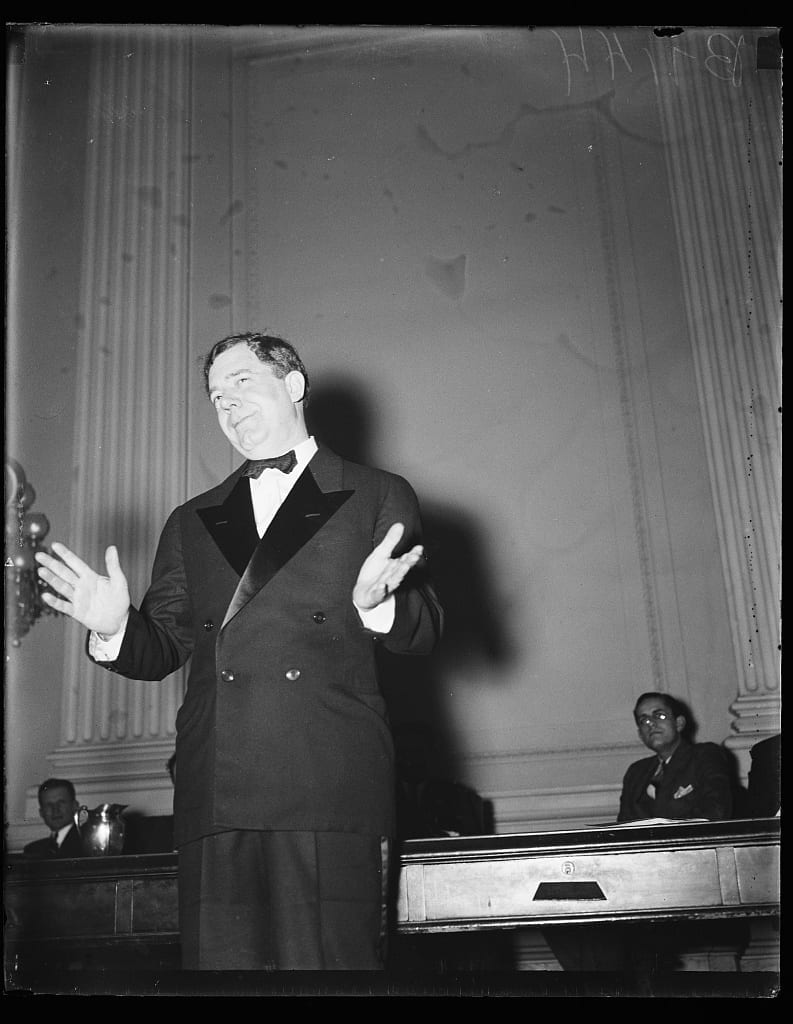

Ironically, the New Deal movement toward more programmatic party politics made party politics less important. This was an unintended consequence of Roosevelt’s use of the direct primary to enforce party discipline. The spread of this campaign innovation put an emphasis on candidates and campaigns rather than on big issues like party principles or platforms. This was particularly true in states with “open” primaries that allowed voters to cast a ballot in any primary regardless of their previous affiliation. In all, Roosevelt’s experience with the primaries set the stage for the parties’ later struggles with managing primaries and building cohesiveness. And Roosevelt’s efforts to lead the nation through the primary process was not successful.

—Eric C. Sands

Source: Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Fireside Chat (on Primaries),” June 24, 1938. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Wooley, The American Presidency Project. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/208978

. . . And now following out this line of thought, I want to say a few words about the coming political primaries.

Fifty years ago party nominations were generally made in conventions—a system typified in the public imagination by a little group in a smoke-filled room who made out the party slates.

The direct primary was invented to make the nominating process a more democratic one — to give the party voters themselves a chance to pick their party candidates.

What I am going to say to you tonight does not relate to the primaries of any particular political party, but to matters of principle in all parties—Democratic, Republican, Farmer-Labor, Progressive, Socialist or any other. Let that be clearly understood.

It is my hope that everybody affiliated with any party will vote in the primaries, and that every such voter will consider the fundamental principles for which his party is on record. That makes for a healthy choice between the candidates of the opposing parties on Election Day in November.

An election cannot give a country a firm sense of direction if it has two or more national parties which merely have different names but are as alike in their principles and aims as peas in the same pod.

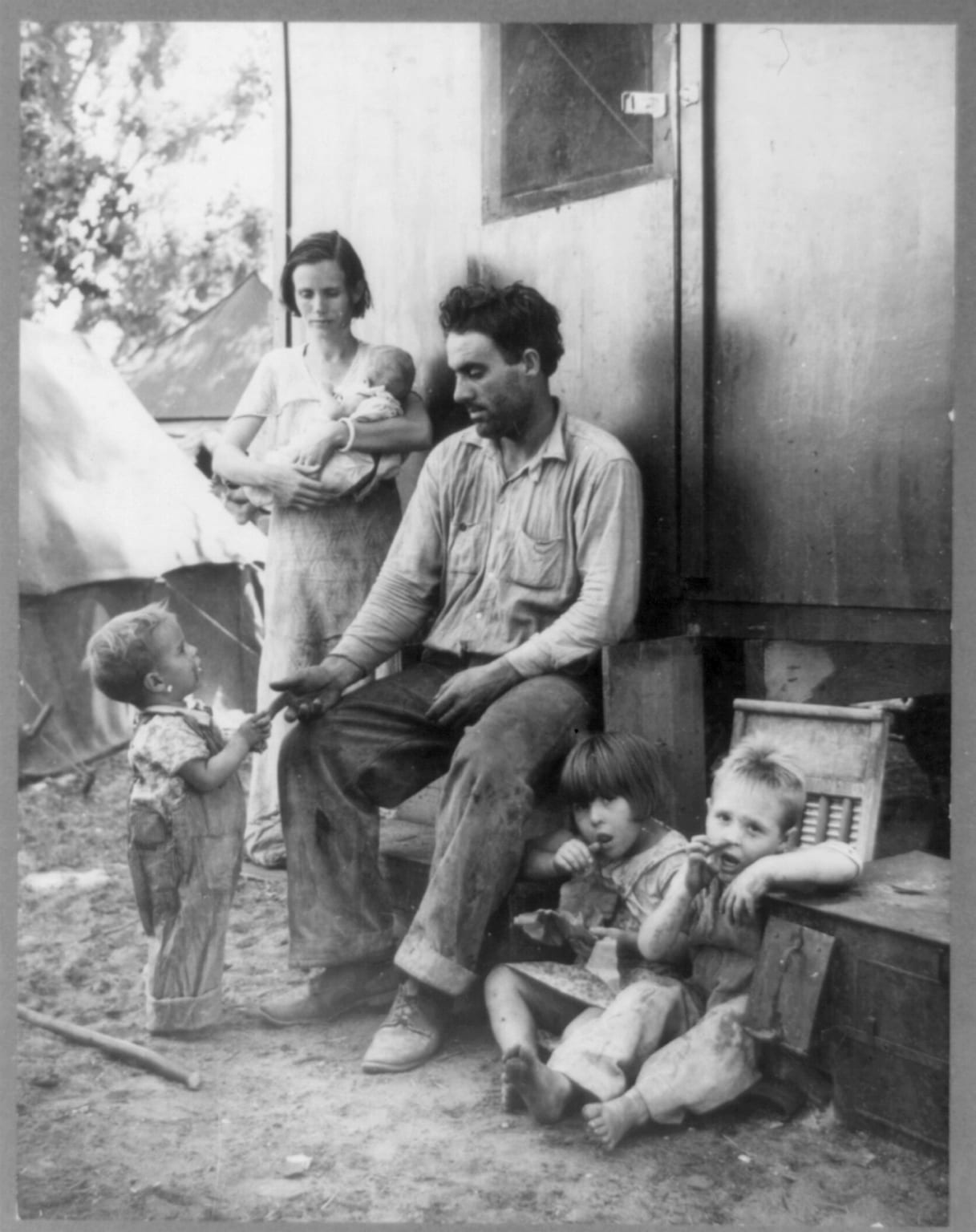

In the coming primaries in all parties, there will by many clashes between two schools of thought, generally classified as liberal and conservative. Roughly speaking, the liberal school of thought recognizes that the new conditions throughout the world call for new remedies.

Those of us in America who hold to this school of thought, insist that these new remedies can be adopted and successfully maintained in this country under our present form of government if we use government as an instrument of cooperation to provide these remedies. We believe that we can solve our problems through continuing effort, through democratic processes instead of Fascism or Communism. We are opposed to the kind of moratorium on reform which, in effect, is reaction itself.

Be it clearly understood, however, that when I use the word “liberal”, I mean the believer in progressive principles of democratic, representative government and not the wild man who, in effect, leans in the direction of Communism, for that is just as dangerous as Fascism.

The opposing or conservative school of thought, as a general proposition, does not recognize the need for Government itself to step in and take action to meet these new problems. It believes that individual initiative and private philanthropy will solve them—that we ought to repeal many of the things we have done and go back, for instance, to the old gold standard, or stop all this business of old age pensions and unemployment insurance, or repeal the Securities and Exchange Act, or let monopolies thrive unchecked—return, in effect, to the kind of Government we had in the twenties.

Assuming the mental capacity of all the candidates, the important question which it seems to me the primary voter must ask is this: “To which of these general schools of thought does the candidate belong”?

As President of the United States, I am not asking the voters of the country to vote for Democrats next November as opposed to Republicans or members of any other party. Nor am I, as President, taking part in Democratic primaries.

As the head of the Democratic Party, however, charged with the responsibility of carrying out the definitely liberal declaration of principles set forth in the 1936 Democratic platform, I feel that I have every right to speak in those few instances where there may be a clear issue between candidates for a Democratic nomination involving these principles, or involving a clear misuse of my own name.

Do not misunderstand me. I certainly would not indicate a preference in a State primary merely because a candidate, otherwise liberal in outlook, had conscientiously differed with me on any single issue. I should be far more concerned about the general attitude of a candidate toward present day problems and his own inward desire to get practical needs attended to in a practical way. We all know that progress may be blocked by outspoken reactionaries and also by those who say “yes” to a progressive objective, but who always find some reason to oppose any specific proposal to gain that objective. I call that type of candidate a “yes, but” fellow.

And I am concerned about the attitude of a candidate or his sponsors with respect to the rights of American citizens to assemble peaceably and to express publicly their views and opinions on important social and economic issues. There can be no constitutional democracy in any community which denies to the individual his freedom to speak and worship as he wishes. The American people will not be deceived by anyone who attempts to suppress individual liberty under the pretense of patriotism.

This being a free country with freedom of expression—especially with freedom of the press—there will be a lot of mean blows struck between now and Election Day. By “blows” I mean misrepresentation, personal attack and appeals to prejudice. It would be a lot better, of course, if campaigns everywhere could be waged with arguments instead of blows.

I hope the liberal candidates will confine themselves to argument and not resort to blows. In nine cases out of ten the speaker or writer who, seeking to influence public opinion, descends from calm argument to unfair blows hurts himself more than his opponent.

The Chinese have a story on this—a story based on three or four thousand years of civilization: Two Chinese coolies were arguing heatedly in the midst of a crowd. A stranger expressed surprise that no blows were being struck. His Chinese friend replied; “The man who strikes first admits that his ideas have given out.”

I know that neither in the summer primaries nor in the November elections will the American voters fail to spot the candidate whose ideas have given out.