Introduction

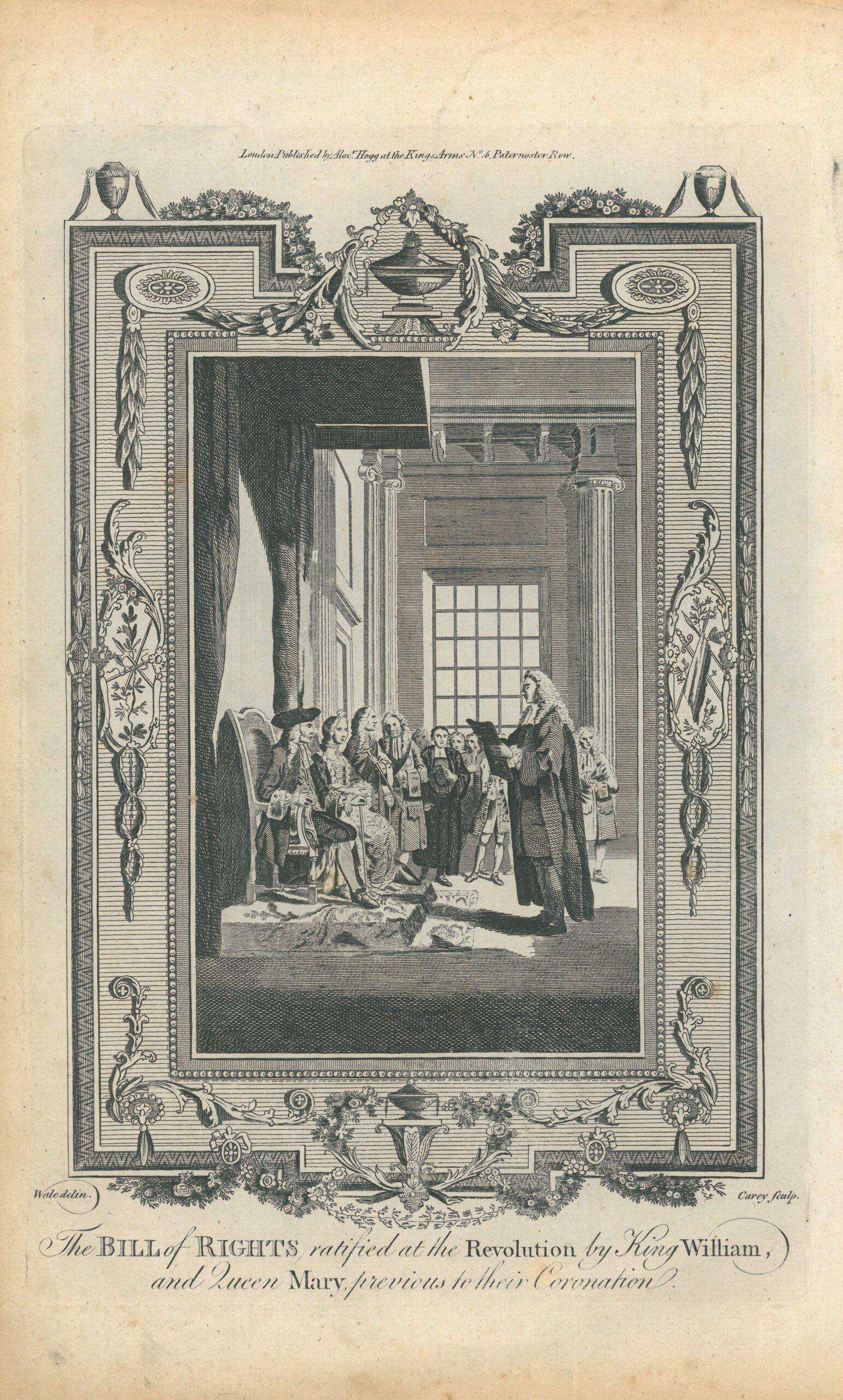

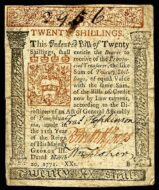

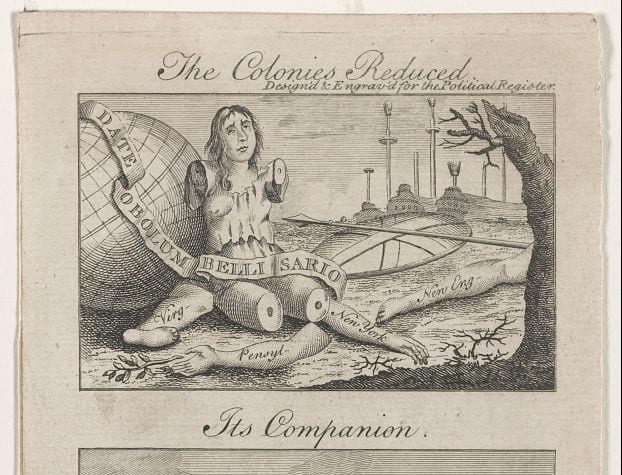

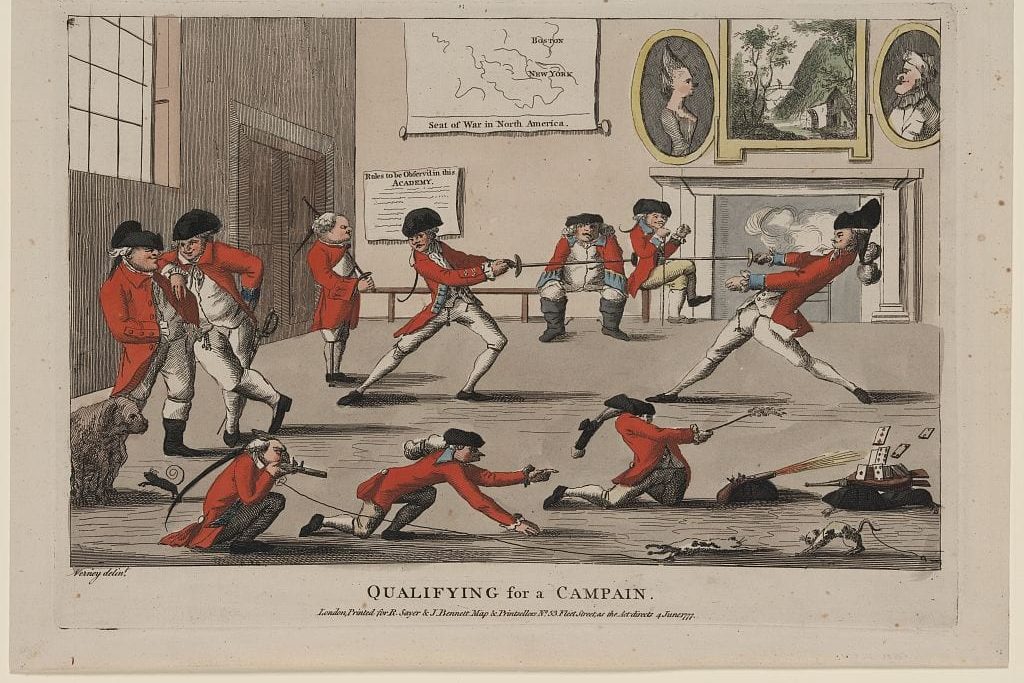

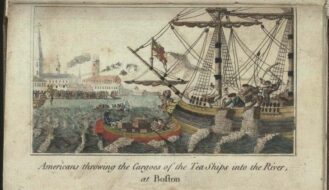

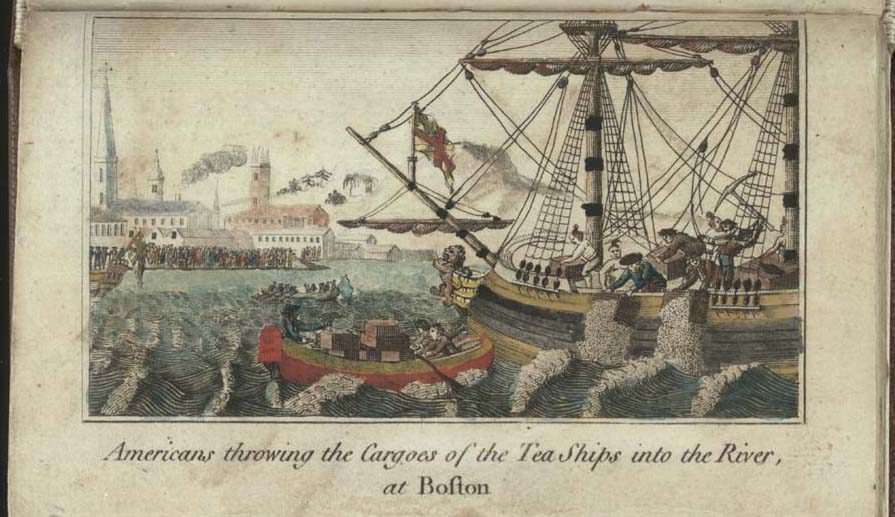

Colonists who celebrated the 1766 repeal of the Stamp Act turned a blind eye to the Declaratory Act, which accompanied the Stamp Act’s termination and asserted Parliament’s “full power and authority” to impose its will on the American colonies “in all cases whatsoever.” The 1767 Townshend Acts, promoted by Chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townshend, alerted them to Parliament’s commitment to increasing revenue from America, which still contributed only about a tenth of what it cost to station British troops on its frontiers.

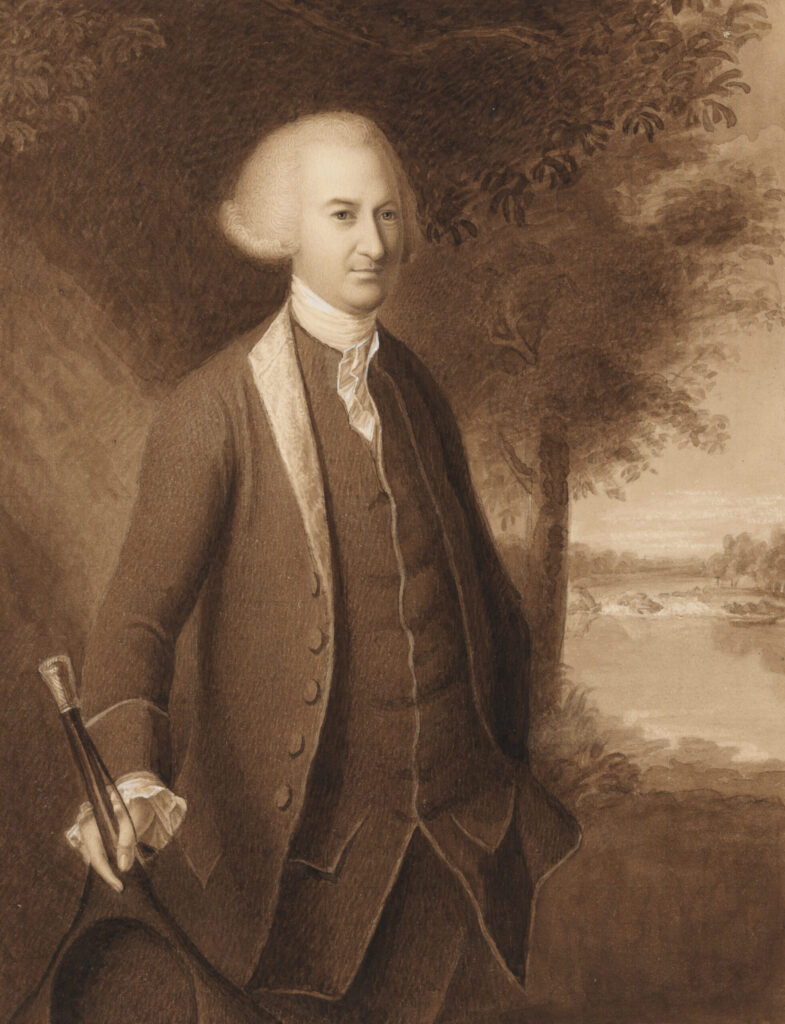

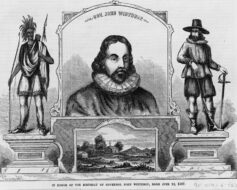

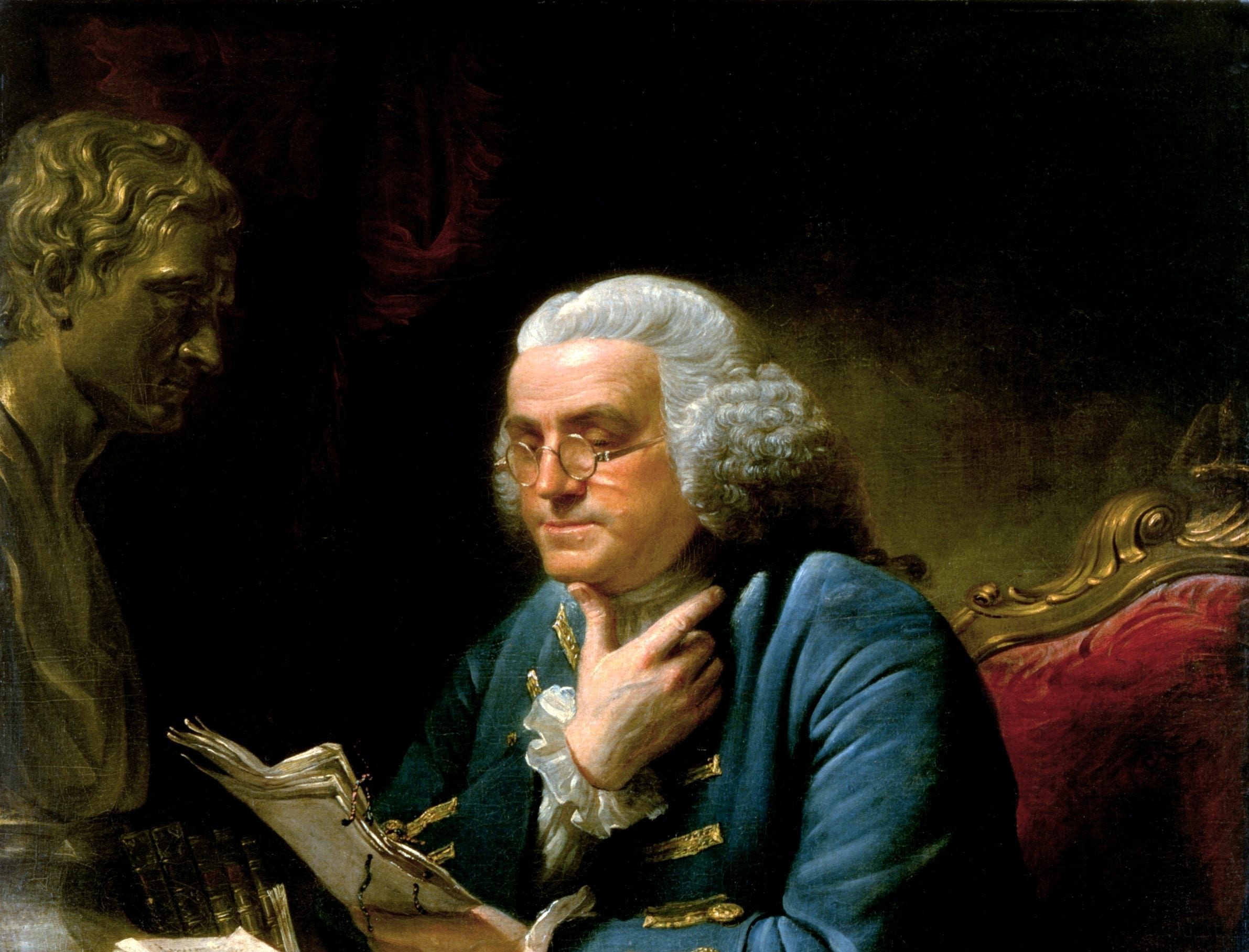

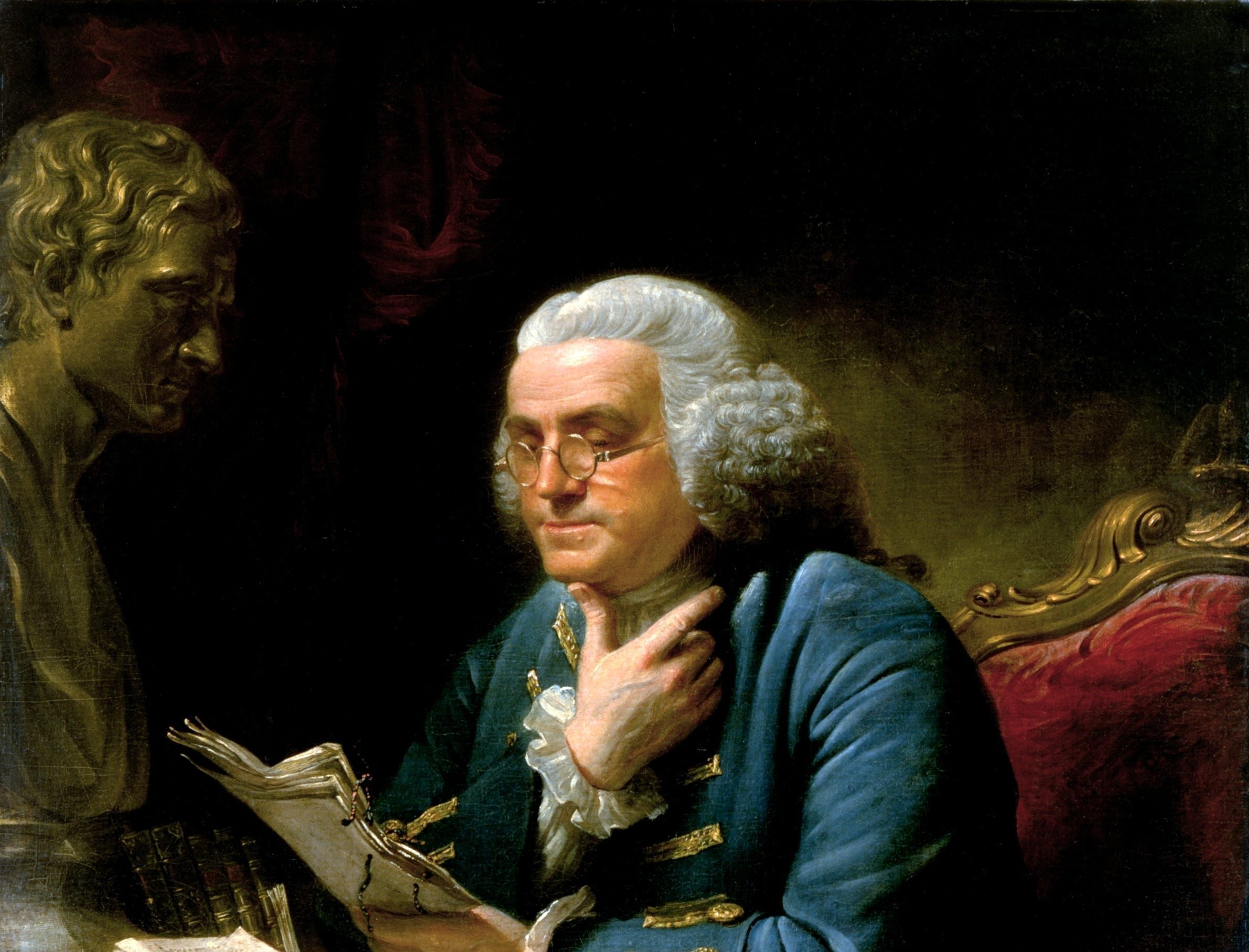

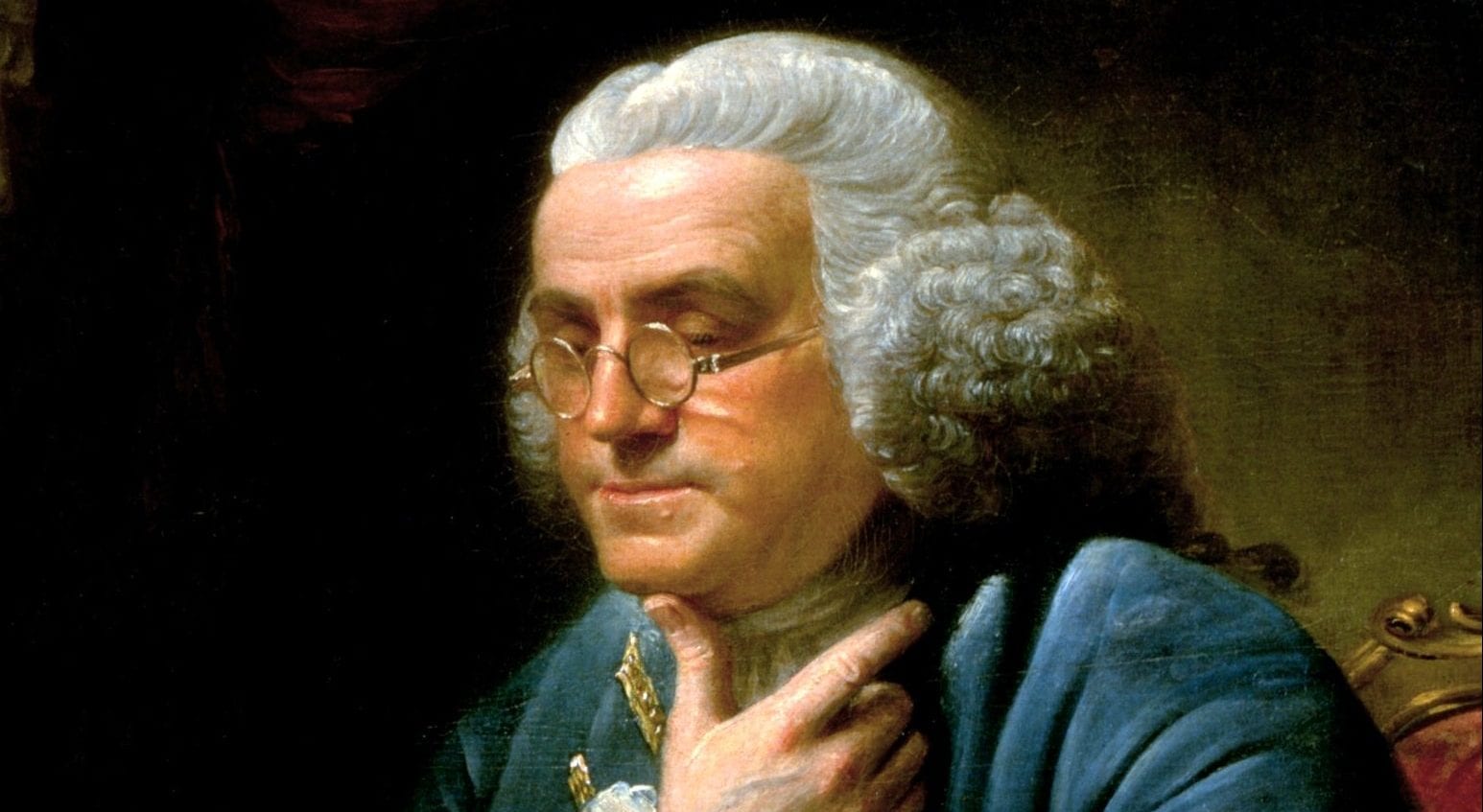

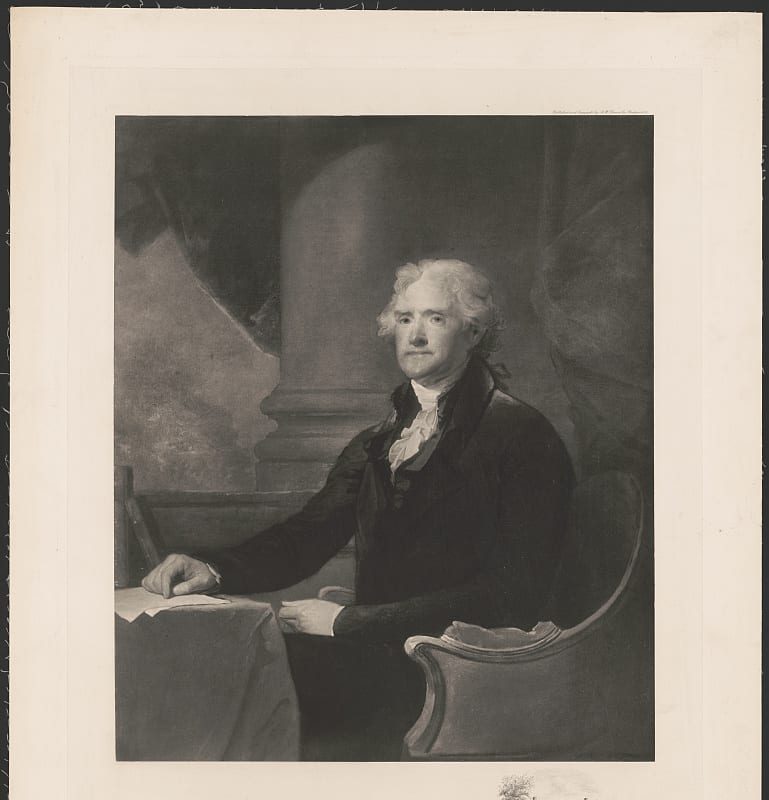

Philadelphia lawyer John Dickinson (1732–1808) picked up his pen in opposition to Townshend’s laws, which imposed taxes on lead, glass, paint, paper, and tea. Posing as an ordinary farmer, this former (and future) Pennsylvania legislator, who had drafted the resolutions of the Stamp Act Congress, made the case that colonists who acquiesced to these taxes would be allowing Parliament to “take money out of our pockets, without our consent.” Newspapers up and down the Atlantic coast published his “Farmer’s Letters,” which also appeared bound together as a pamphlet. Thomas Jefferson, who would serve with Dickinson in the Continental Congress, later described him as “among the first of the advocates for the rights of his country.” When Dickinson died in 1808, Jefferson wrote that a “truer patriot … could not have left us.”

—Robert M.S. McDonald

Source: Paul Leicester Ford, ed., The Writings of John Dickinson (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1895), 1:312–22. https://archive.org/details/writingsofjohndi00dickrich/page/312

My dear countrymen,

There is another late act of Parliament, which appears to me to be unconstitutional, and as destructive to the liberty of these colonies, as that mentioned in my last letter; that is, the act for granting the duties on paper, glass, etc.

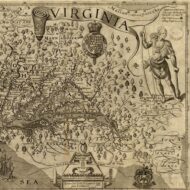

The Parliament unquestionably possesses a legal authority to regulate the trade of Great Britain, and all her colonies. Such an authority is essential to the relation between a mother country and her colonies; and necessary for the common good of all. He, who considers these provinces as states distinct from the British Empire, has very slender notions of justice, or of their interests. We are but parts of a whole; and therefore there must exist a power somewhere to preside and preserve the connection in due order. This power is lodged in the Parliament; and we are as much dependent on Great Britain, as a perfectly free people can be on another.

I have looked over every statute relating to these colonies, from their first settlement to this time; and I find every one of them founded on this principle, till the Stamp Act administration. All before, are calculated to regulate trade, and preserve or promote a mutually beneficial intercourse between the several constituent parts of the empire; and though many of them imposed duties on trade, yet those duties were always imposed with design to restrain the commerce of one part, that was injurious to another, and thus to promote the general welfare. The raising a revenue thereby was never intended…. Never did the British Parliament, till the period above mentioned, think of imposing duties in America, FOR THE PURPOSE OF RAISING A REVENUE….

This I call an innovation; and a most dangerous innovation. It may perhaps be objected, that Great Britain has a right to lay what duties she pleases upon her exports, and it makes no difference to us, whether they are paid here or there.

To this I answer. These colonies require many things for their use, which the laws of Great Britain prohibit them from getting anywhere but from her. Such are paper and glass.

That we may legally be bound to pay any general duties on these commodities, relative to the regulation of trade, is granted; but we being obliged by the laws to take from Great Britain, any special duties imposed on their exportations to us only, with intention to raise a revenue from us only, are as much taxes, upon us, as those imposed by the Stamp Act….

Some persons perhaps may say, that this act lays us under no necessity to pay the duties imposed, because we may ourselves manufacture the articles on which they are laid; whereas by the Stamp Act no instrument of writing could be good, unless made on British paper, and that too stamped.

Such an objection amounts to no more than this, that the injury resulting to these colonies, from the total disuse of British paper and glass, will not be so afflicting as that which would have resulted from the total disuse of writing among them; for by that means even the Stamp Act might have been eluded. Why then was it universally detested by them as slavery itself? Because it presented to these devoted provinces nothing but a choice of calamities, embittered by indignities, each of which it was unworthy of freemen to bear. But is no injury a violation of right but the greatest injury? If… eluding the payment of the taxes imposed by the Stamp Act, would have subjected us to a more dreadful inconvenience, than… eluding the payment of those imposed by the late act; does it therefore follow, that the last is no violation of our rights, though it is calculated for the same purpose the other was, that is, to raise money upon us, WITHOUT OUR CONSENT?…

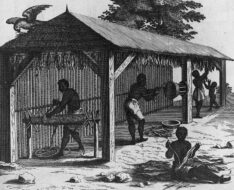

But the objectors may further say, that we shall suffer no injury at all by the disuse of British paper and glass. We might not, if we could make as much as we want. But can any man, acquainted with America, believe this possible? I am told there are but two or three glasshouses on this continent, and but very few paper mills; and suppose more should be erected, a long course of years must elapse, before they can be brought to perfection. This continent is a country of planters, farmers, and fishermen; not of manufacturers. The difficulty of establishing particular manufactures in such a country is almost insuperable. For one manufacture is connected with others in such a manner that it may be said to be impossible to establish one or two without establishing several others. The experience of many nations may convince us of this truth….

Great Britain has prohibited the manufacturing iron and steel in these colonies, without any objection being made to her right of doing it. The like right she must have to prohibit any other manufacture among us. Thus she is possessed of an undisputed precedent on that point. This authority, she will say, is founded on the original intention of settling these colonies; that is, that we should manufacture for them, and that they should supply her with materials. The equity of this policy, she will also say, has been universally acknowledged by the colonies, who never have made the least objection to statutes for that purpose; and will further appear by the mutual benefits flowing from this usage ever since the settlement of these colonies….

Here then, my dear countrymen, ROUSE yourselves, and behold the ruin hanging over your heads….

Upon the whole, the single question is, whether the Parliament can legally impose duties to be paid by the people of these colonies only, FOR THE SOLE PURPOSE OF RAISING A REVENUE, on commodities which she obliges us to take from her alone, or, in other words, whether the Parliament can legally take money out of our pockets, without our consent….

A Farmer