Introduction

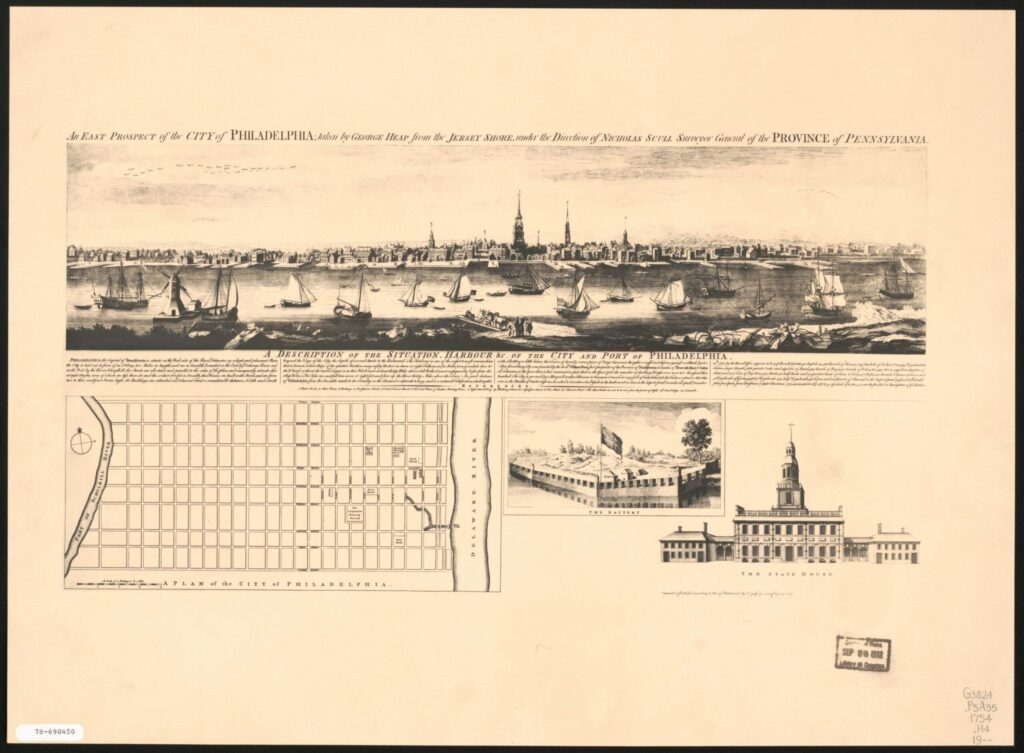

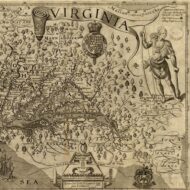

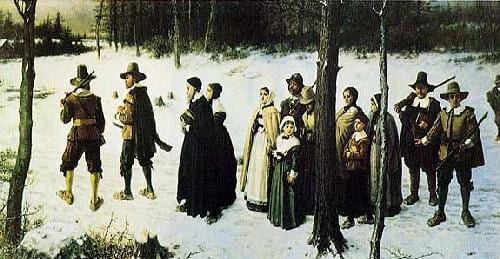

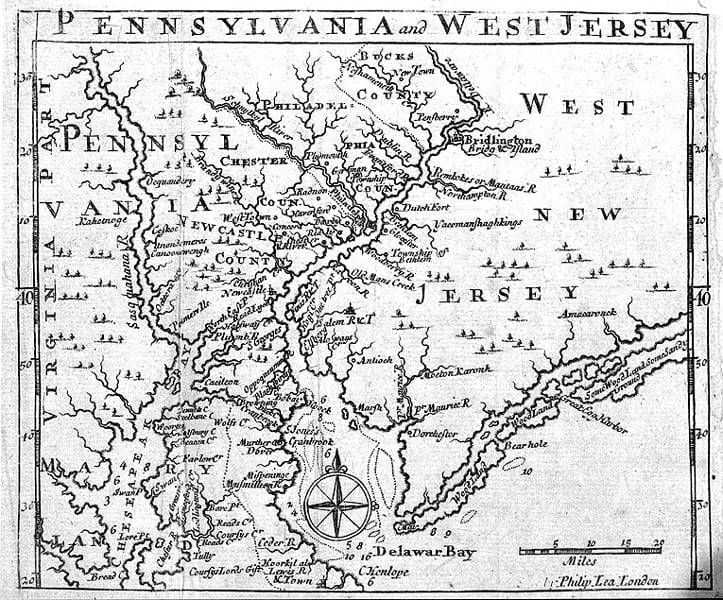

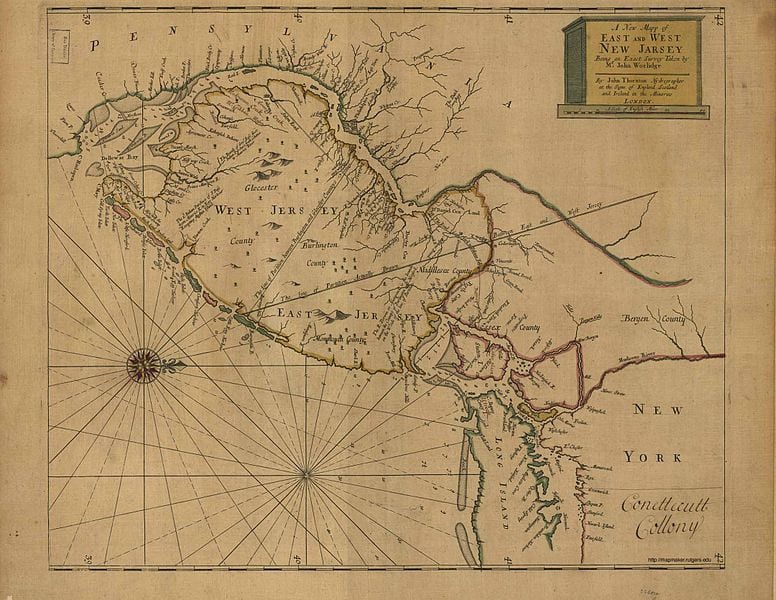

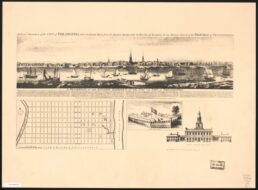

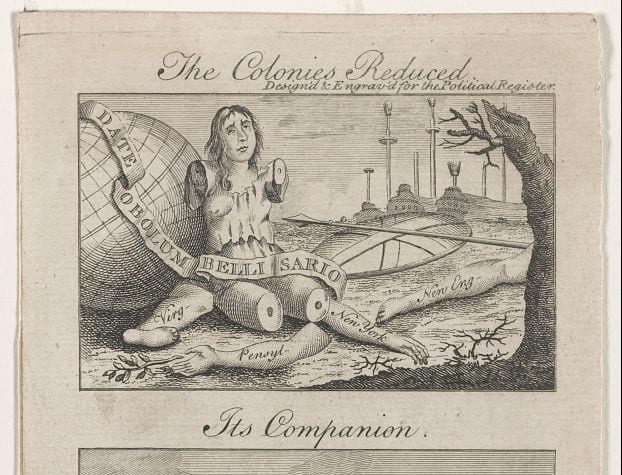

When they settled in North America, the colonists brought their religious beliefs with them. In most instances, this was accomplished not only as a matter of social or cultural transmission, but by acts of legislative authority that provided public funding for certain religious denominations and not for others. Only Pennsylvania, Delaware, Rhode Island and (possibly) New Jersey failed to establish a particular denomination at some point during the colonial period: in the other colonies, religious establishments were the norm, and generally seen as for the institutional benefit of both church and state, as well as in accordance with the public good. Some colonies (such as Maryland and New York) combined religious establishments with limited toleration for religious dissenters. Yet even in Pennsylvania, although the law was ostensibly “tolerant” of religious variety and protective of freedom of conscience in principle, there remained an underlying presumption that individual religious faith in a broadly Protestant sense (sometimes extended to include Catholics and, more rarely, Jews) was a necessary component of civil order.

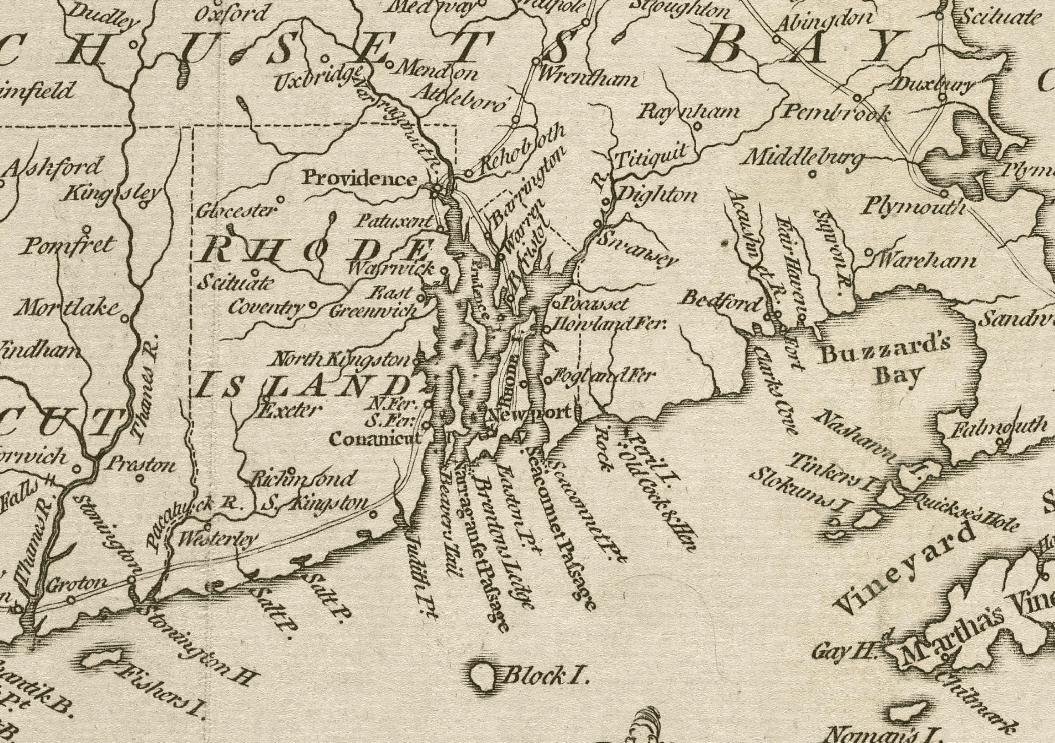

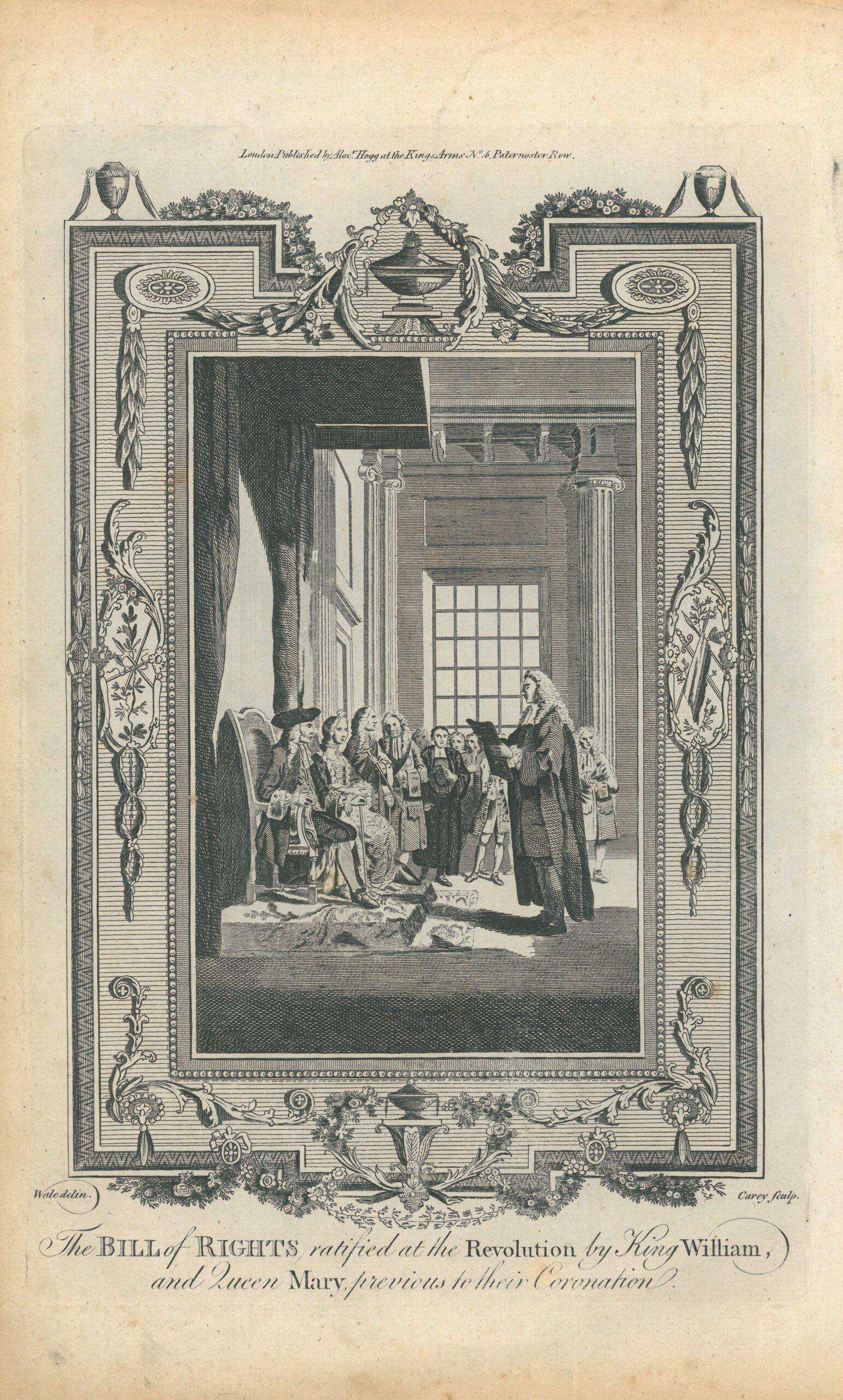

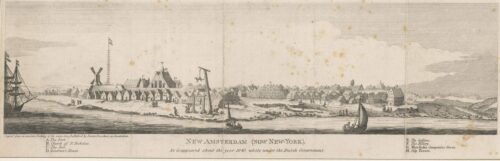

The difficulty of maintaining this latter assumption while at the same time holding to an expansive understanding of freedom of conscience became even more apparent when, following the Glorious Revolution, William and Mary signed the Toleration Act of 1689 granting freedom of worship to all Protestants regardless of sect throughout the British Empire. England and her Atlantic colonies soon became a haven for religious refugees from less-tolerant European regimes. After their arrival in places like New York, which already had large and religiously diverse non-English populations, the colonies began to seem “very much divided,” at least in the eyes of those used to greater religious conformity. Indeed, the vibrant but worrisome diversity of religion in the colonies was the impetus behind efforts to establish the Church of England more strongly as a means of asserting royal authority and creating greater political as well as cultural unity.

As scholar and statesman Elisha Williams’ tract, The Essential Rights and Liberties of Protestants, makes clear, however, for many colonists, religious freedom was seen as a natural and inalienable right, one that they would increasingly associate with other political rights worth fighting for – with words when possible, and weapons when necessary – as the century wore on.

Gottlieb Mittelberger, Journey to Pennsylvania in the Year 1750, Carl Theo. Eben, trans. (Philadelphia: John Jos. McVey, 1898), 31-32, 54-55, 62-63. Gottlieb Mittelberger (1714 – 1758) was a Lutheran pastor in Pennsylvania for several years in the early 1750s.

For there are many doctrines of faith and sects in Pennsylvania which cannot all be enumerated, because many a one will not confess to what faith he belongs.

Besides, there are many hundreds of adult persons who have not been and do not even wish to be baptized. There are many who think nothing of the sacraments and the Holy Bible, nor even of God and his word. Many do not even believe that there is a true God and devil, a heaven and a hell, salvation and damnation, a resurrection of the dead, a judgment and an eternal life; they believe that all one can see is natural. For in Pennsylvania every one may not only believe what he will, but he may even say it freely and openly.

Consequently, when young persons, not yet grounded in religion, come to serve for many years with such free-thinkers and infidels, and are not sent to any church or school by such people, especially when they live far from any school or church. Thus, it happens that such innocent souls come to no true divine recognition, and grow up like heathens and Indians. . . .

Coming to speak of Pennsylvania again, that colony possesses great liberties above all other English colonies, inasmuch as all religious sects are tolerated there. We find there Lutherans, Reformed, Catholics, Quakers, Mennonists or Anabaptists, Herrnhuters or Moravian Brethren, Pietists, Seventh Day Baptists, Dunkers, Presbyterians, Newborn, Freemasons, Separatists, Freethinkers, Jews, Mohammedans, Pagans, Negroes and Indians. The Evangelicals and Reformed, however, are in the majority. But there are many hundred unbaptized souls there that do not even wish to be baptized. Many pray neither in the morning nor in the evening, neither before nor after meals. No devotional book, not to speak of a Bible, will be found with such people. In one house and one family, 4, 5, and even 6 sects may be found. . . .

The preachers throughout Pennsylvania have no power to punish any one, or to compel any one to go to church; nor has anyone a right to dictate to the other, because they are not supported by any Consistorio. Most preachers are hired by the year like cowherds in Germany; and if one does not preach to their liking, he must expect to be served with a notice that his services will no longer be required. It is, therefore, very difficult to be a conscientious preacher, especially as they have to hear and suffer much from so many hostile and often wicked sects. The most exemplary preachers are often reviled, insulted, and scoffed at like the Jews, by the young and old, especially in the country. I would, therefore, rather perform the meanest herdsman’s duties in Germany than be a preacher in Pennsylvania. Such unheard-of rudeness and wickedness spring from the excessive liberties of the land, and from the blind zeal of the many sects. To many a one’s soul and body, liberty in Pennsylvania is more hurtful than useful. There is a saying in that country: Pennsylvania is the heaven of the farmers, the paradise of the mechanics, and the hell of the officials and preachers.