No study questions

No related resources

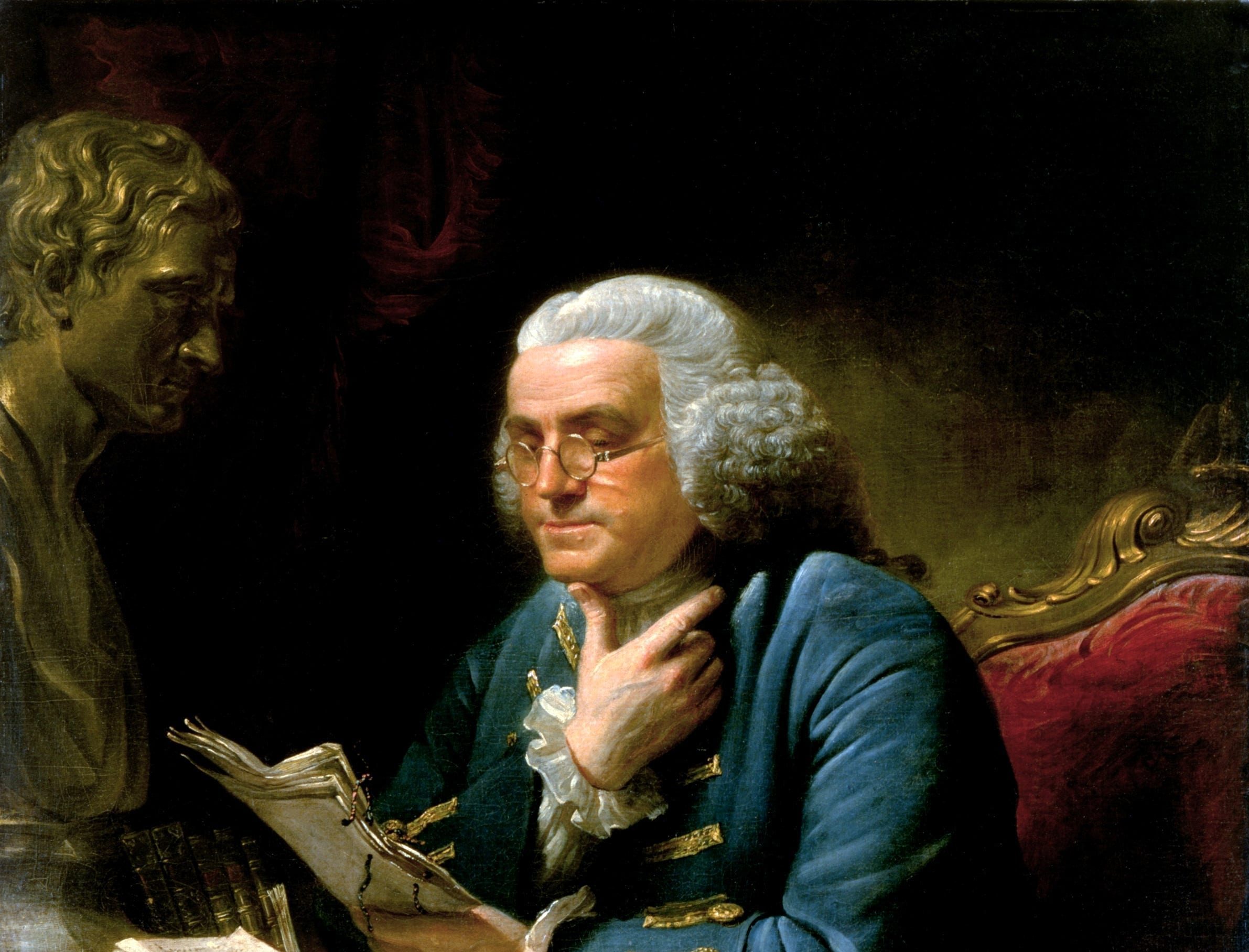

Introduction

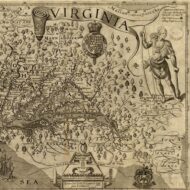

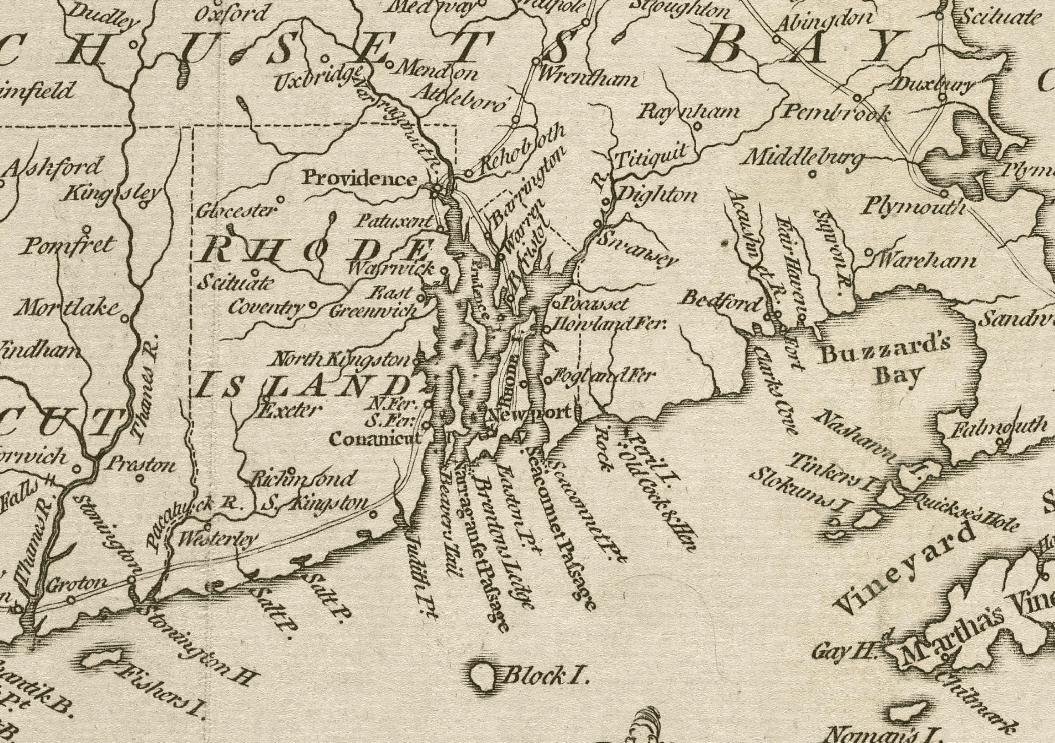

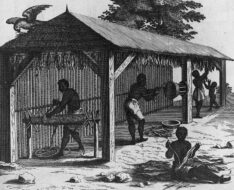

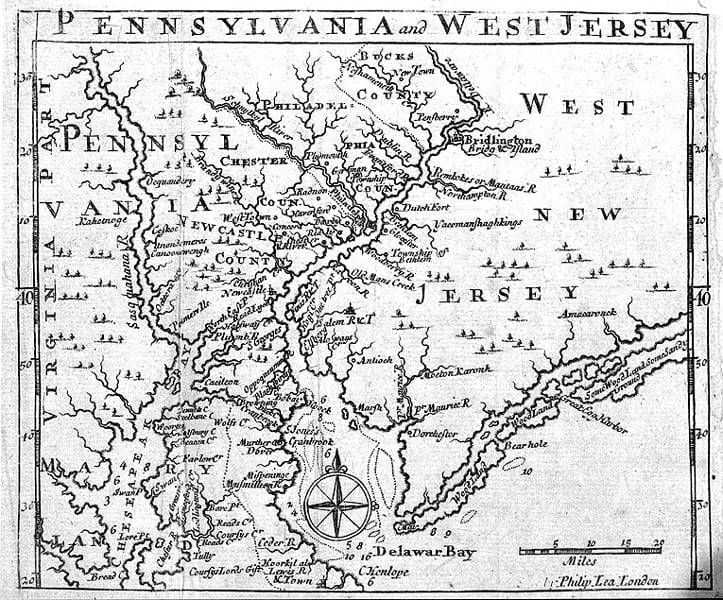

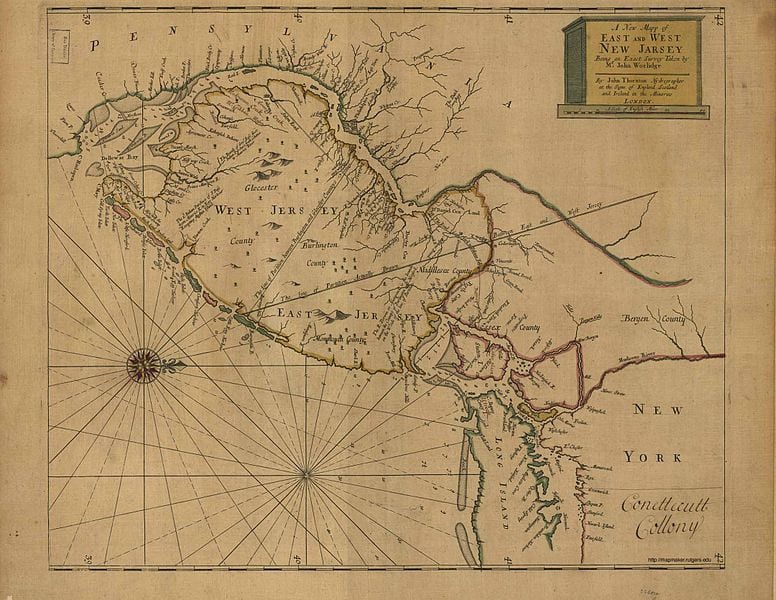

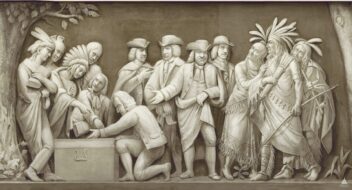

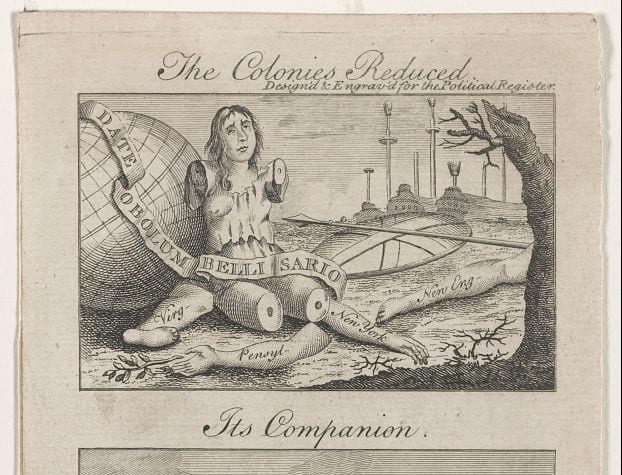

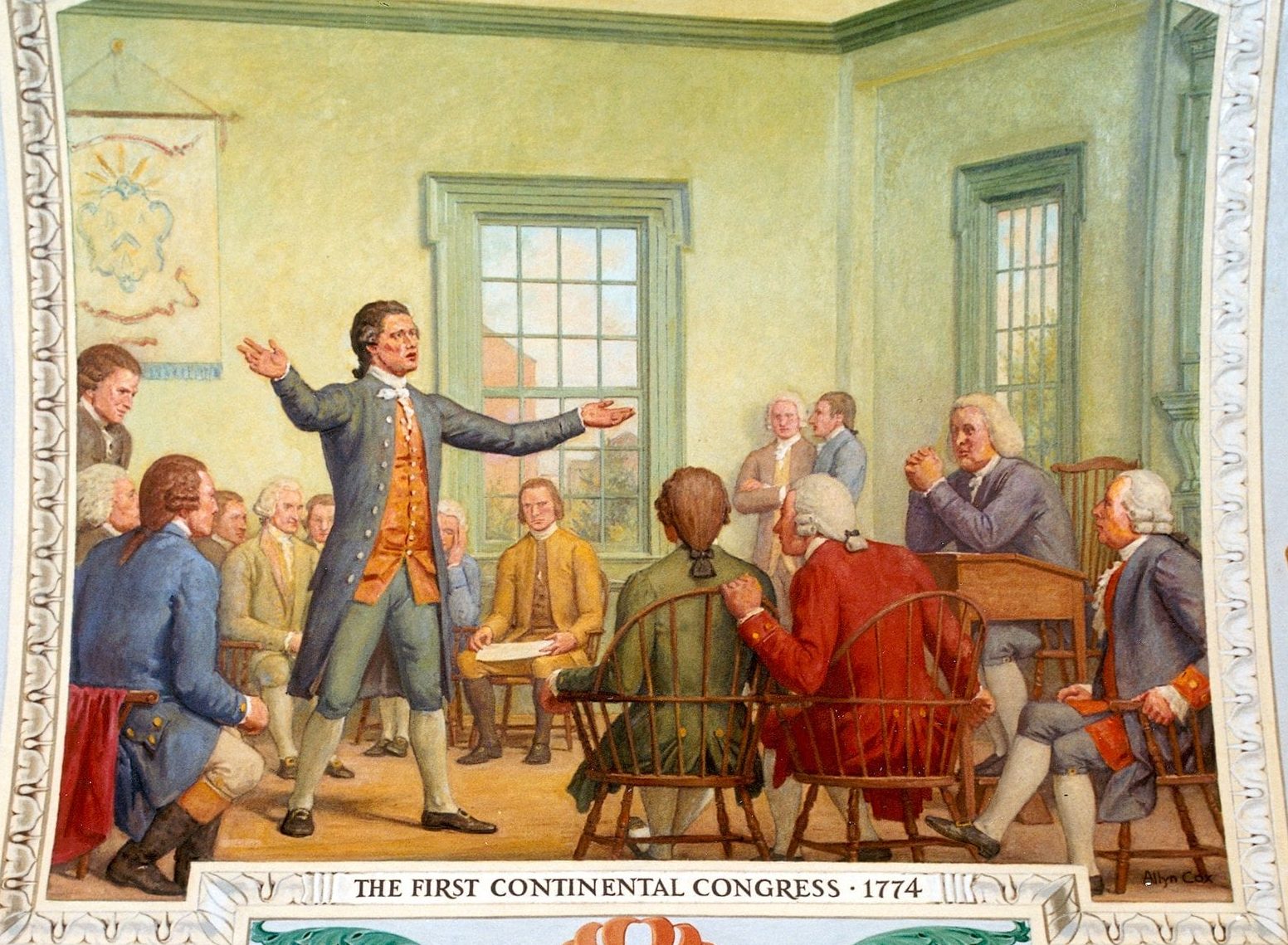

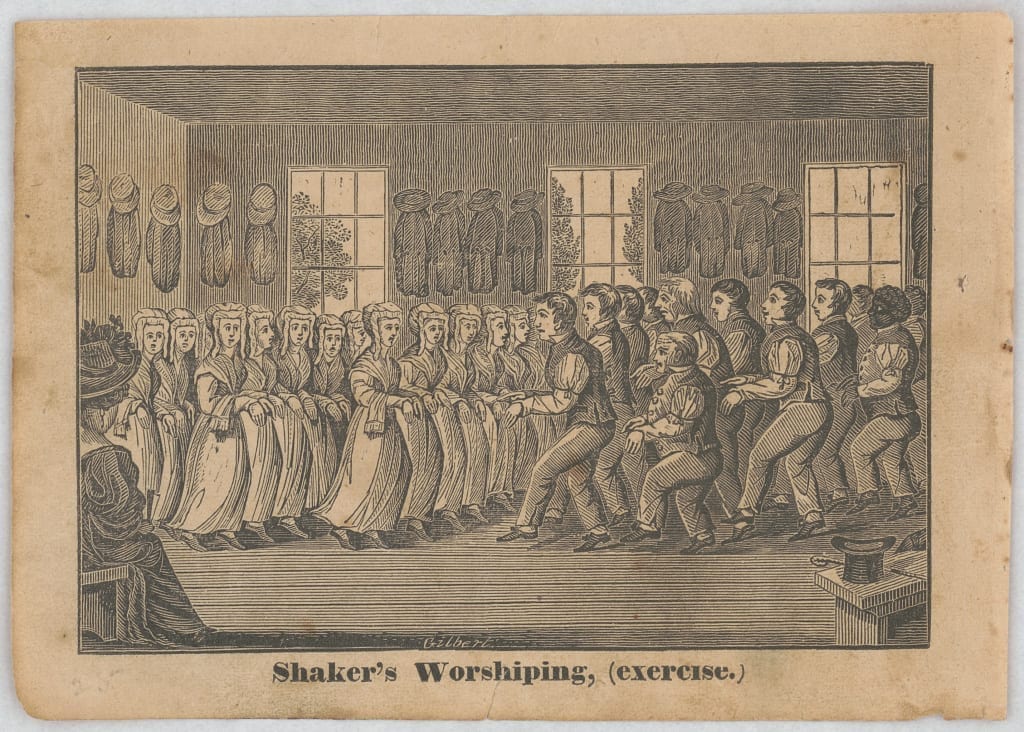

When they settled in North America, the colonists brought their religious beliefs with them. In most instances, this was accomplished not only as a matter of social or cultural transmission, but by acts of legislative authority that provided public funding for certain religious denominations and not for others. Only Pennsylvania, Delaware, Rhode Island and (possibly) New Jersey failed to establish a particular denomination at some point during the colonial period: in the other colonies, religious establishments were the norm, and generally seen as for the institutional benefit of both church and state, as well as in accordance with the public good. Some colonies (such as Maryland and New York) combined religious establishments with limited toleration for religious dissenters. Yet even in Pennsylvania, although the law was ostensibly “tolerant” of religious variety and protective of freedom of conscience in principle, there remained an underlying presumption that individual religious faith in a broadly Protestant sense (sometimes extended to include Catholics and, more rarely, Jews) was a necessary component of civil order.

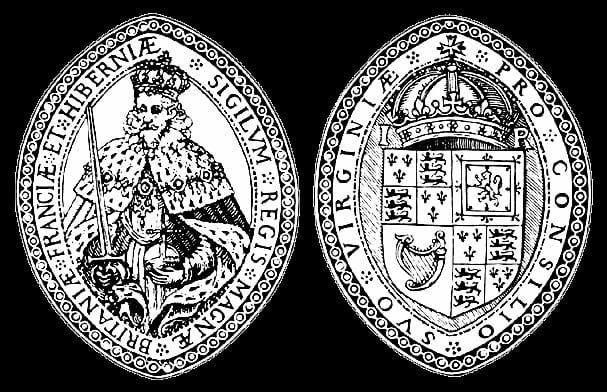

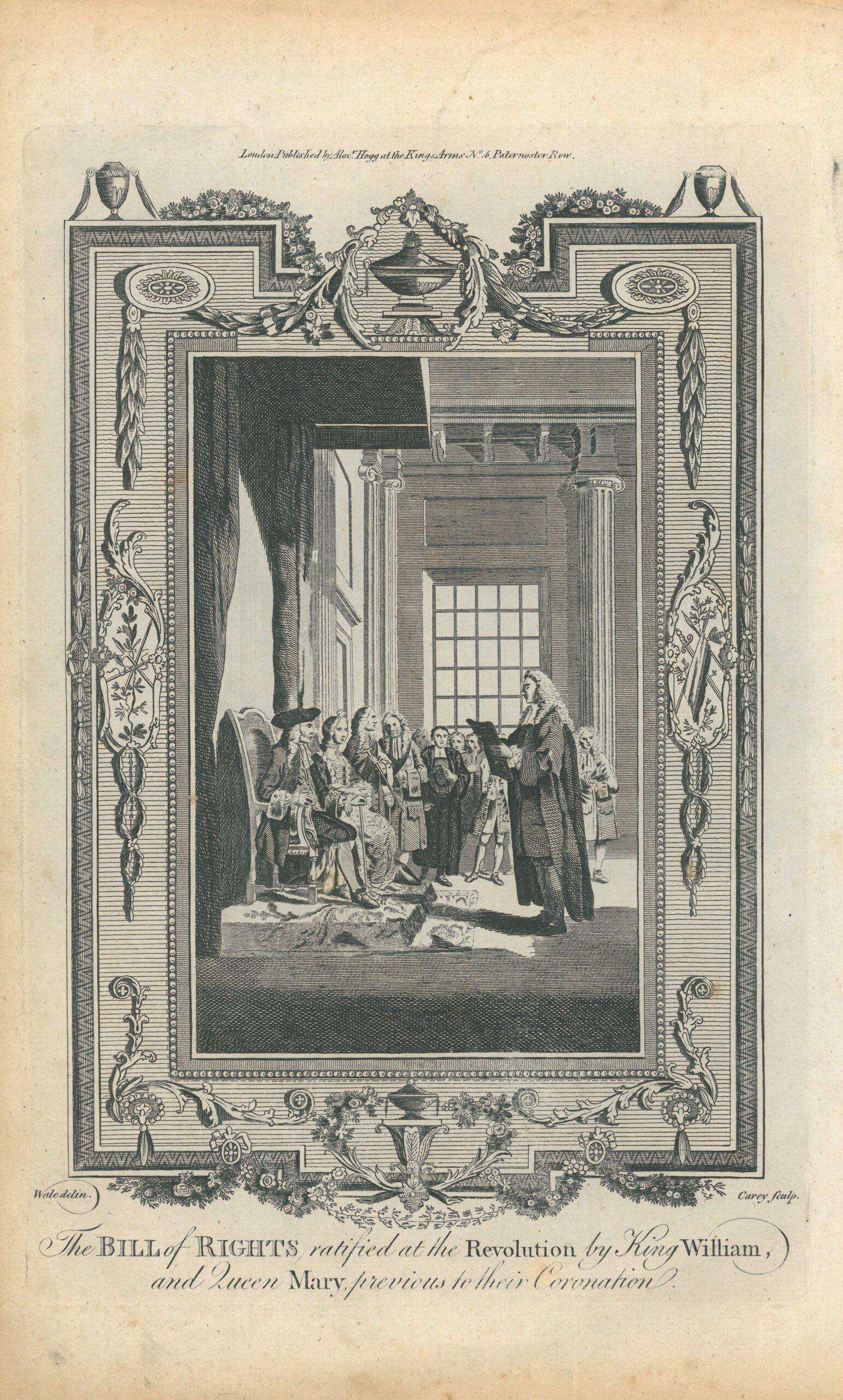

The difficulty of maintaining this latter assumption while at the same time holding to an expansive understanding of freedom of conscience became even more apparent when, following the Glorious Revolution, William and Mary signed the Toleration Act of 1689 granting freedom of worship to all Protestants regardless of sect throughout the British Empire. England and her Atlantic colonies soon became a haven for religious refugees from less-tolerant European regimes. After their arrival in places like New York, which already had large and religiously diverse non-English populations, the colonies began to seem “very much divided,” at least in the eyes of those used to greater religious conformity. Indeed, the vibrant but worrisome diversity of religion in the colonies was the impetus behind efforts to establish the Church of England more strongly as a means of asserting royal authority and creating greater political as well as cultural unity.

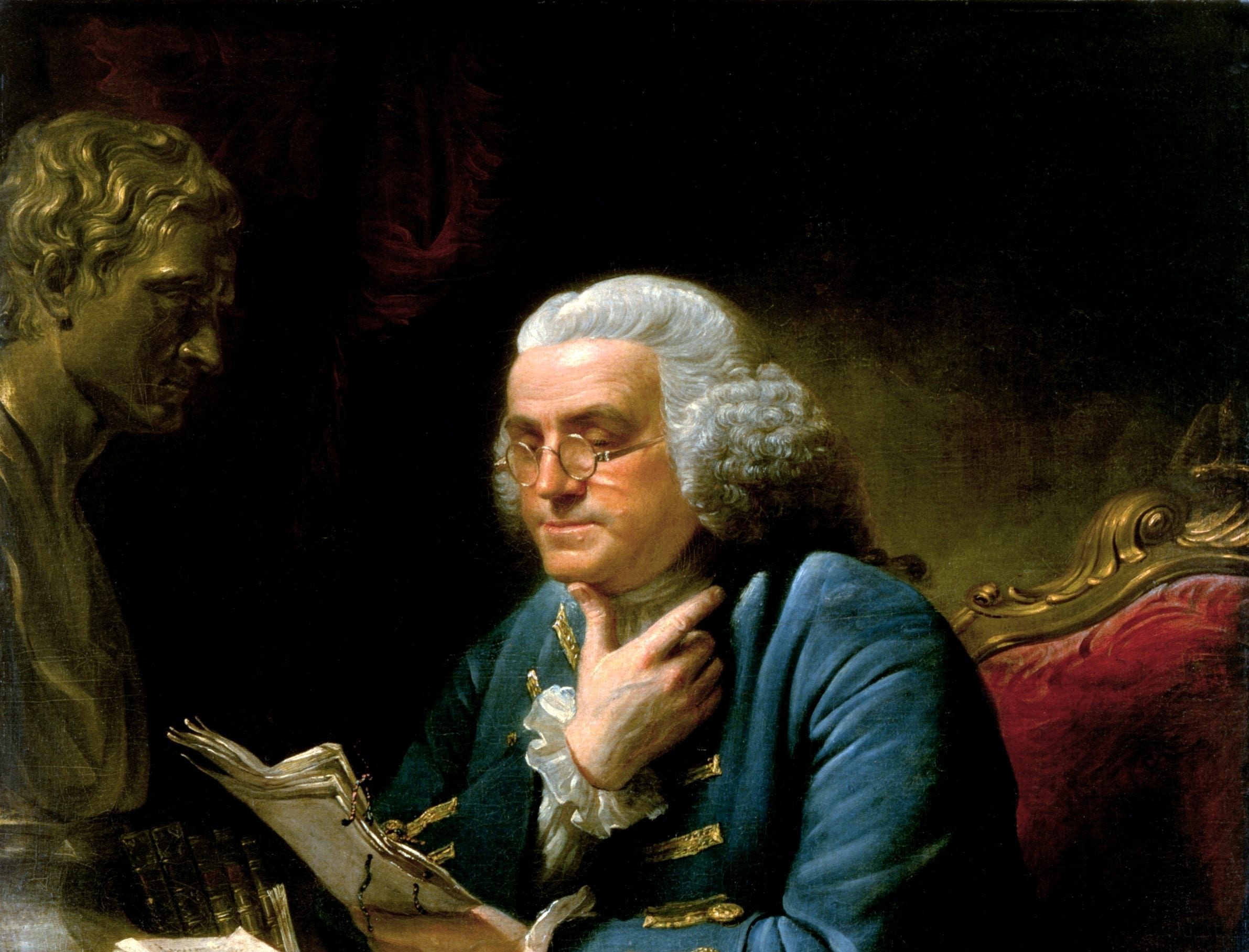

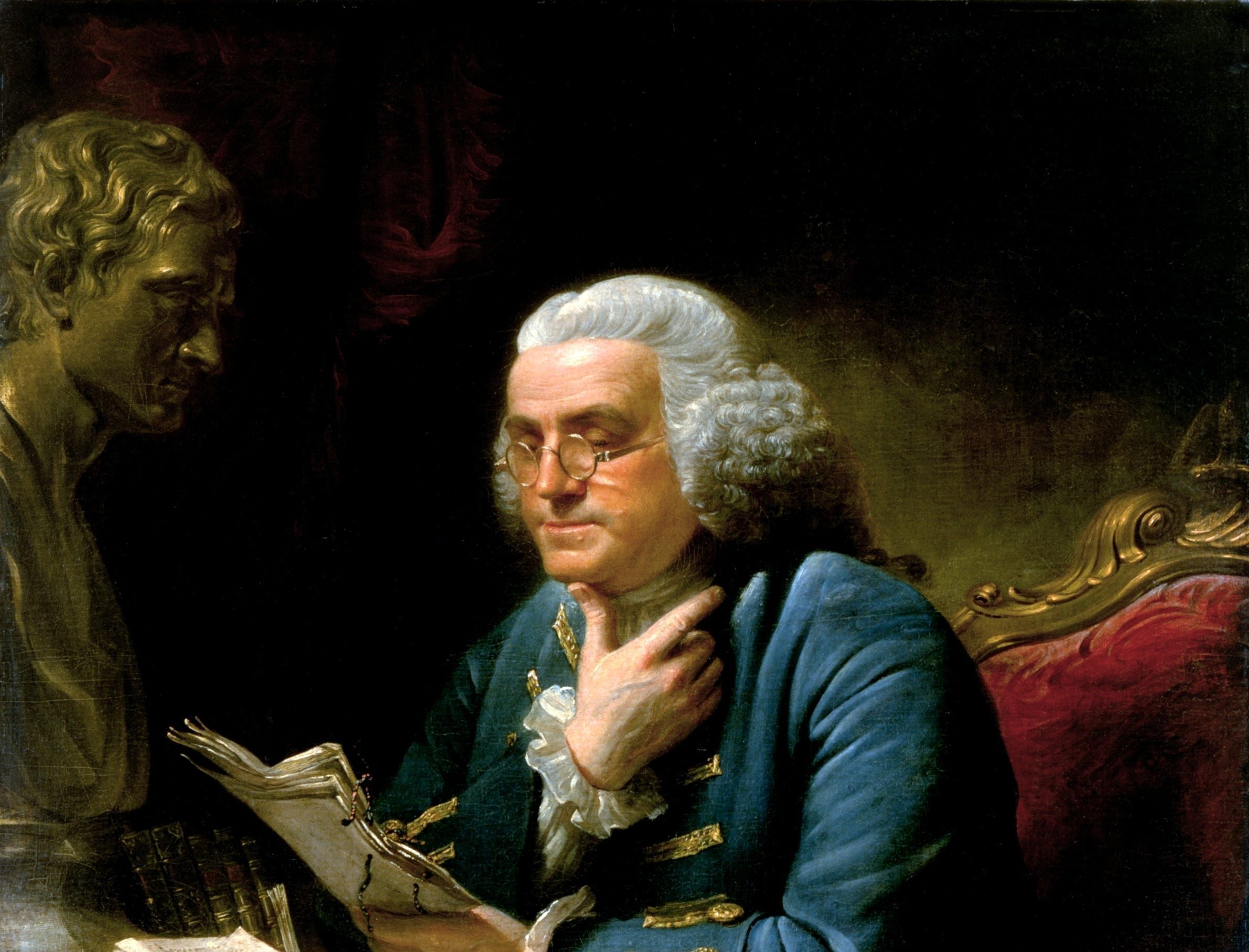

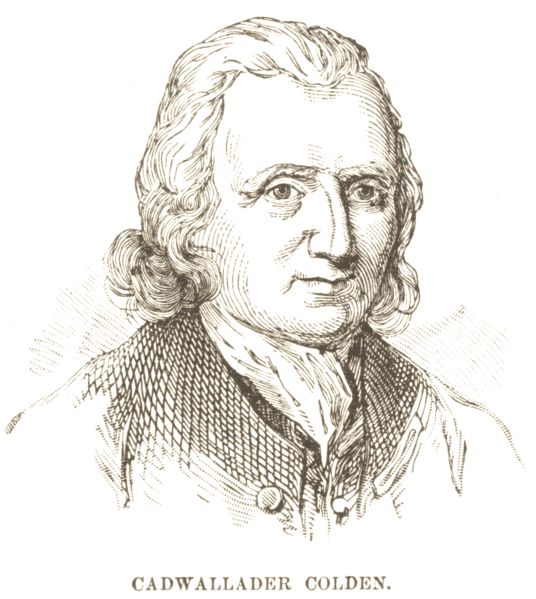

As scholar and statesman Elisha Williams’ tract, The Essential Rights and Liberties of Protestants, makes clear, however, for many colonists, religious freedom was seen as a natural and inalienable right, one that they would increasingly associate with other political rights worth fighting for – with words when possible, and weapons when necessary – as the century wore on.

In Donald S. Lutz, Colonial Origins of the American Constitution: A Documentary History, ed. Donald S. Lutz (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund 1998). Available online at: https://goo.gl/QkEqTD. As Lutz points out, the sections are misnumbered in the original and there is no Section iv.

Whereas the glory of almighty God and the good of mankind is the reason and end of government and, therefore, government in itself is a venerable ordinance of God. And forasmuch as it is principally desired and intended by the Proprietary1 and Governor and the freemen of the province of Pennsylvania and territories thereunto belonging to make and establish such laws as shall best preserve true Christian and civil liberty in opposition to all unchristian, licentious, and unjust practices, whereby God may have his due, Caesar his due,2 and the people their due, from tyranny and oppression on the one side and insolence and licentiousness on the other, so that the best and firmest foundation may be laid for the present and future happiness of both the Governor and people of the province and territories aforesaid and their posterity.

Be it, therefore, enacted by William Penn, Proprietary and Governor, by and with the advice and consent of the deputies of the freemen of this province and counties aforesaid in assembly met and by the authority of the same, that these following chapters and paragraphs shall be the laws of Pennsylvania and the territories thereof.

Chap. i. Almighty God, being only Lord of conscience, father of lights and spirits, and the author as well as object of all divine knowledge, faith, and worship, who can only enlighten the mind and persuade and convince the understandings of people, in due reverence to his sovereignty over the souls of mankind:

Be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, that no person now or at any time hereafter living in this province, who shall confess and acknowledge one almighty God to be the creator, upholder, and ruler of the world, and who professes him or herself obliged in conscience to live peaceably and quietly under the civil government, shall in any case be molested or prejudiced for his or her conscientious persuasion or practice. Nor shall he or she at any time be compelled to frequent or maintain any religious worship, place, or ministry whatever contrary to his or her mind, but shall freely and fully enjoy his, or her, Christian liberty in that respect, without any interruption or reflection. And if any person shall abuse or deride any other for his or her different persuasion and practice in matters of religion, such person shall be looked upon as a disturber of the peace and be punished accordingly.

But to the end that looseness, irreligion, and atheism may not creep in under pretense of conscience in this province, be it further enacted, by the authority aforesaid, that, according to the example of the primitive Christians and for the ease of the creation, every first day of the week, called the Lord’s day, people shall abstain from their usual and common toil and labor that, whether masters, parents, children, or servants, they may the better dispose themselves to read the scriptures of truth at home or frequent such meetings of religious worship abroad as may best suit their respective persuasions.

Chap. ii. And be it further enacted by, etc., that all officers and persons commissioned and employed in the service of the government in this province and all members and deputies elected to serve in the Assembly thereof and all that have a right to elect such deputies shall be such as profess and declare they believe in Jesus Christ to be the son of God, the savior of the world, and that are not convicted of ill-fame or unsober and dishonest conversation and that are of twenty-one years of age at least.

Chap. iii. And be it further enacted, etc., that whosoever shall swear in their common conversation by the name of God or Christ or Jesus, being legally convicted thereof, shall pay, for every such offense, five shillings or suffer five days imprisonment in the house of correction at hard labor to the behoove of the public and be fed with bread and water only during that time.

Chap. v. And be it further enacted, etc., for the better prevention of corrupt communication, that whosoever shall speak loosely and profanely of almighty God, Christ Jesus, the Holy Spirit, or the scriptures of truth, and is legally convicted thereof, shall pay, for every such offense, five shillings or suffer five days imprisonment in the house of correction at hard labor to the behoove of the public and be fed with bread and water only during that time.

Chap. vi. And be it further enacted, etc., that whosoever shall, in their conversation, at any time curse himself or any other and is legally convicted thereof shall pay for every such offense five shillings or suffer five days imprisonment as aforesaid.

- 1. The Penn family, which owned Pennsylvania. It was given to William Penn by King Charles II in 1681 to pay off a debt.

- 2. An allusion to a saying of Jesus quoted in all the synoptic gospels: Matthew 22:21, Mark 12:17, and Luke 20:25. In each version of the story, Jesus resolves a dilemma posed by the Roman requirement that the Jews pay taxes to Caesar.

Charter of Liberties and Privileges

October 30, 1683

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.