Introduction

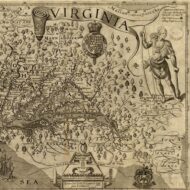

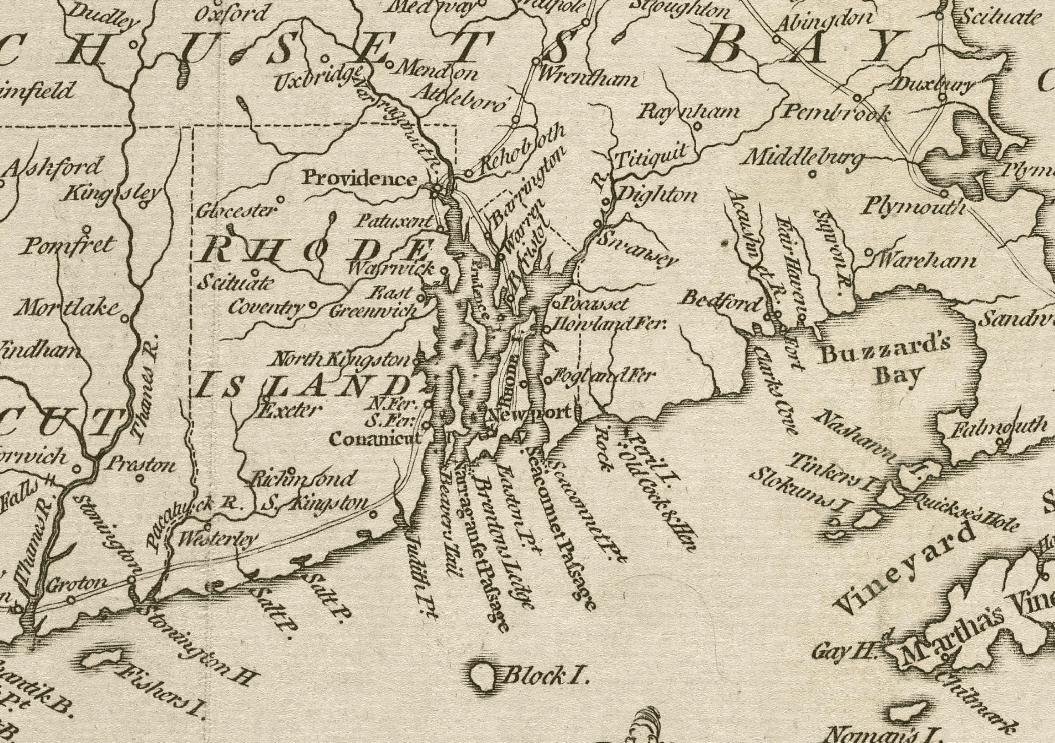

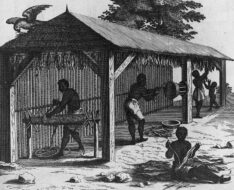

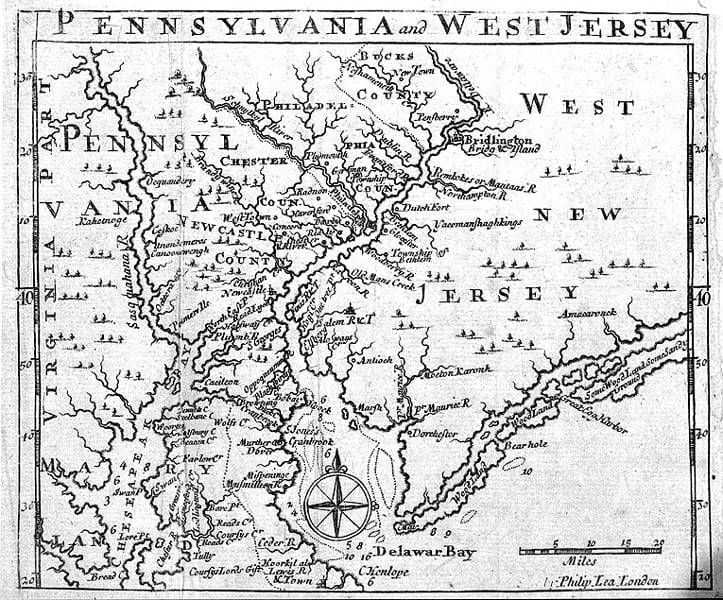

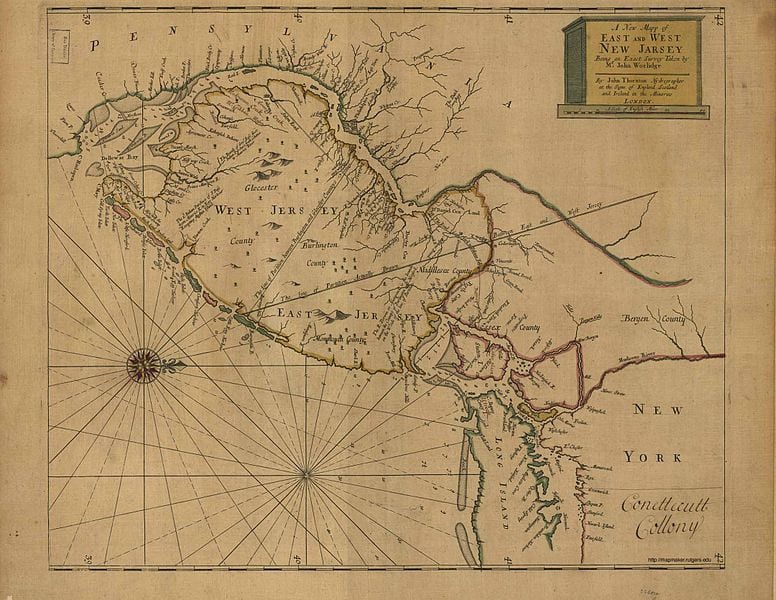

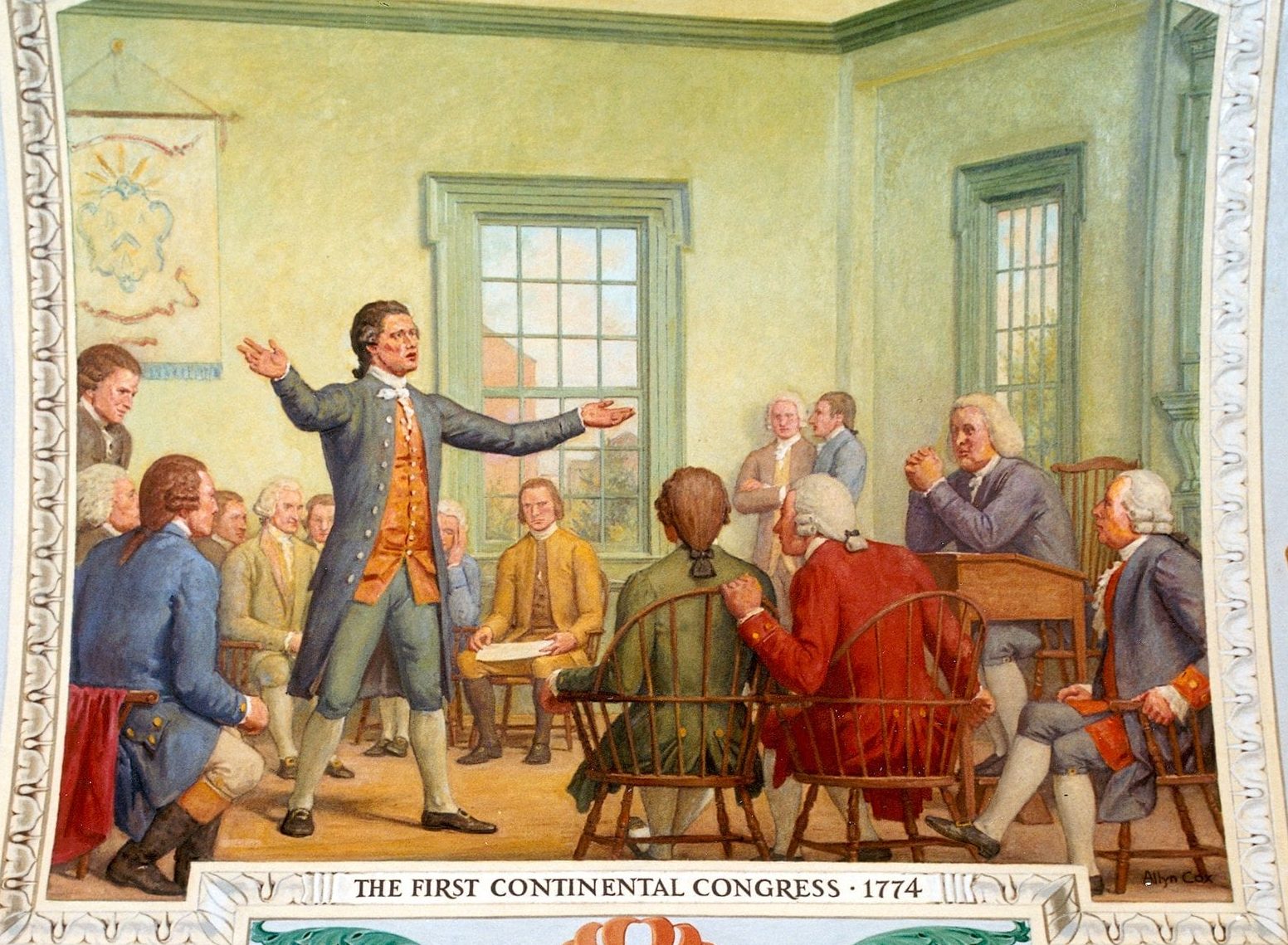

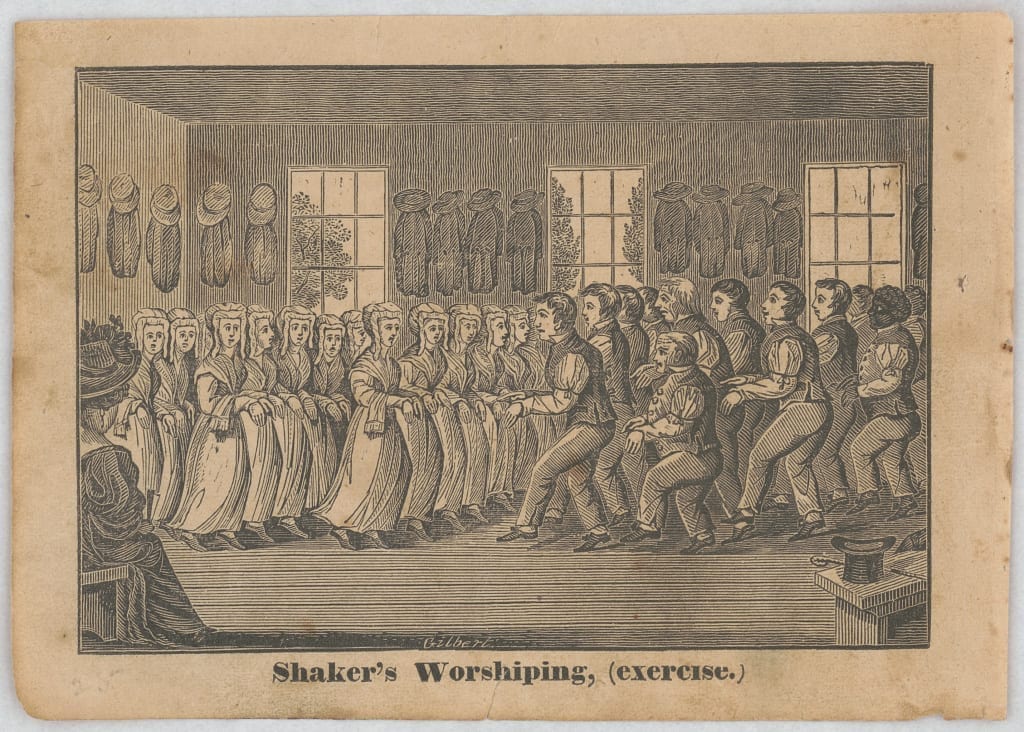

When they settled in North America, the colonists brought their religious beliefs with them. In most instances, this was accomplished not only as a matter of social or cultural transmission, but by acts of legislative authority that provided public funding for certain religious denominations and not for others. Only Pennsylvania, Delaware, Rhode Island and (possibly) New Jersey failed to establish a particular denomination at some point during the colonial period: in the other colonies, religious establishments were the norm, and generally seen as for the institutional benefit of both church and state, as well as in accordance with the public good. Some colonies (such as Maryland and New York) combined religious establishments with limited toleration for religious dissenters. Yet even in Pennsylvania (Pennsylvania: Frame of Government and Pennsylvania: An Act of Freedom of Conscience), although the law was ostensibly “tolerant” of religious variety and protective of freedom of conscience in principle, there remained an underlying presumption that individual religious faith in a broadly Protestant sense (sometimes extended to include Catholics and, more rarely, Jews) was a necessary component of civil order.

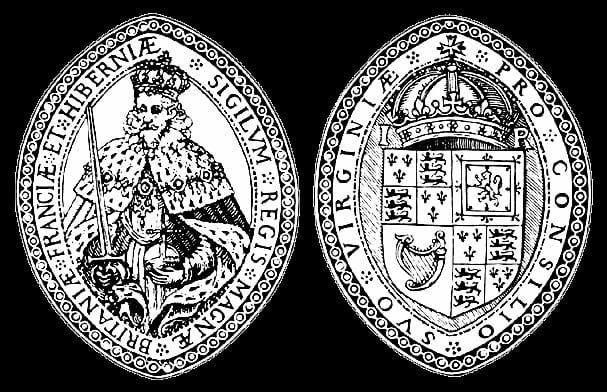

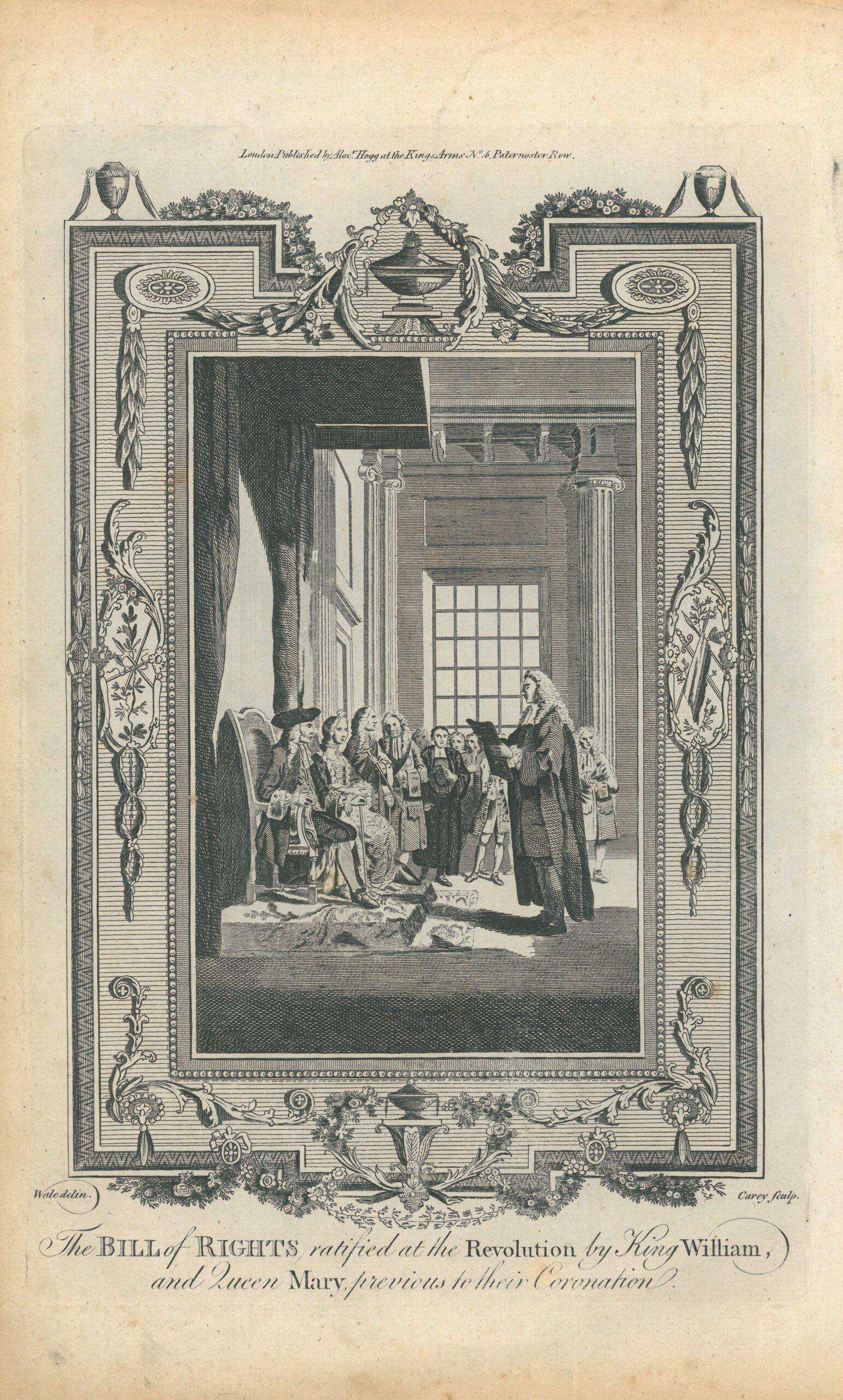

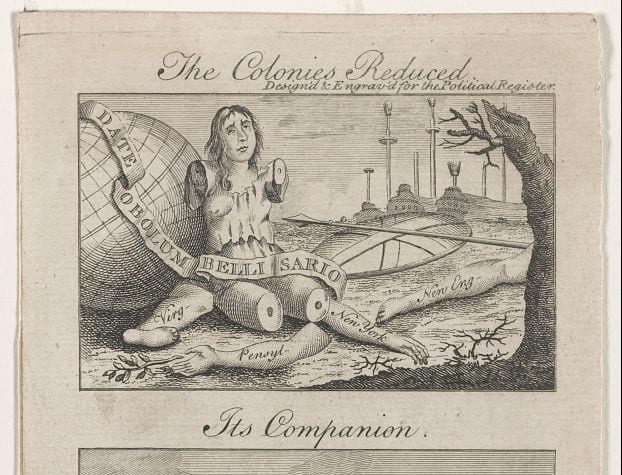

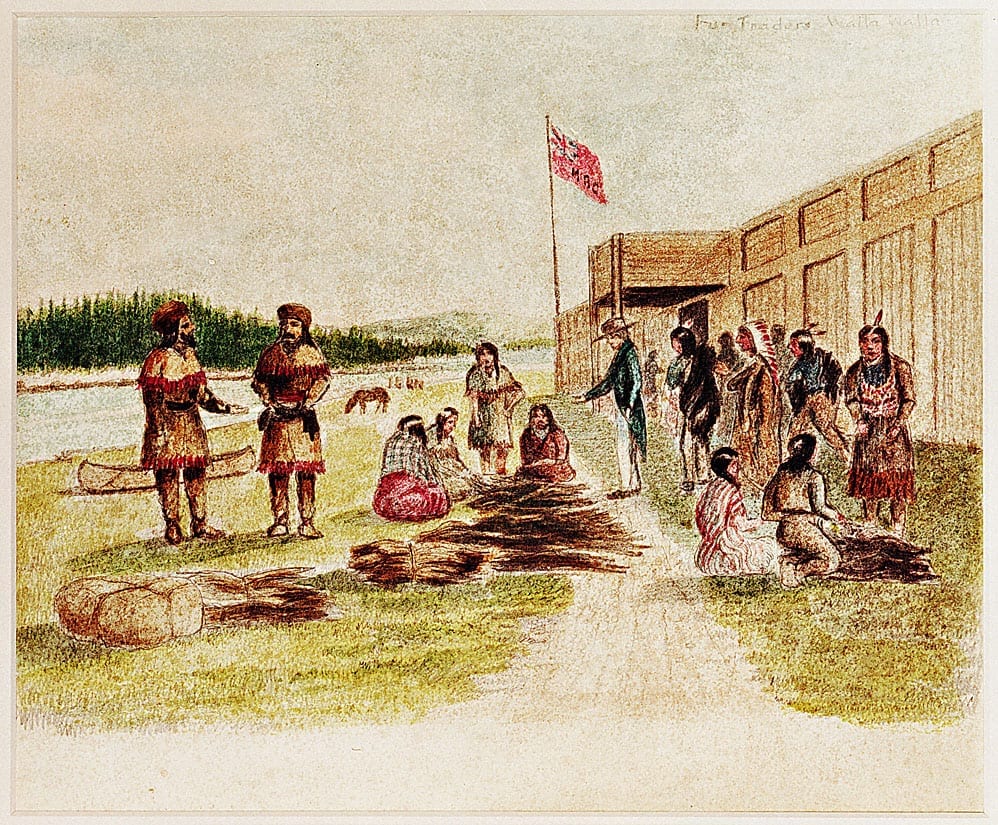

The difficulty of maintaining this latter assumption while at the same time holding to an expansive understanding of freedom of conscience became even more apparent when, following the Glorious Revolution, William and Mary signed the Toleration Act of 1689 granting freedom of worship to all Protestants regardless of sect throughout the British Empire. England and her Atlantic colonies soon became a haven for religious refugees from less-tolerant European regimes. After their arrival in places like New York, which already had large and religiously diverse non-English populations, the colonies began to seem “very much divided,” at least in the eyes of those used to greater religious conformity (“As to their religion, they are very much divided” and “Liberty in Pennsylvania is more hurtful than useful”). Indeed, the vibrant but worrisome diversity of religion in the colonies was the impetus behind efforts to establish the Church of England more strongly as a means of asserting royal authority and creating greater political as well as cultural unity. (See Chapter 5.)

As scholar and statesman Elisha Williams’ tract, The Essential Rights and Liberties of Protestants (The Essential Rights and Liberties of Protestants) makes clear, however, for many colonists, religious freedom was seen as a natural and inalienable right, one that they would increasingly associate with other political rights worth fighting for – with words when possible, and weapons when necessary – as the century wore on.

In Donald S. Lutz, Colonial Origins of the American Constitution: A Documentary History, ed. Donald S. Lutz (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund 1998). Available online at: https://goo.gl/QkEqTD.

THE PREFACE

. . . This the Apostle teaches in diverse of his epistles: “The law (says he) was added because of transgression.” In another place, “Knowing that the law was not made for the righteous man, but for the disobedient and ungodly, for sinners, for unholy and profane, for murderers, for whoremongers, for them that defile themselves with mankind, and for man-stealers, for liars, for perjured persons,” &c.; but this is not all, he opens and carries the matter of government a little further: “Let every soul be subject to the higher powers; for there is no power but of God. The powers that be are ordained of God: whosoever therefore resisteth the power, resisteth the ordinance of God. For rulers are not a terror to good works, but to evil: wilt thou then not be afraid of the power? Do that which is good, and thou shalt have praise of the same.” “He is the minister of God to thee for good.” “Wherefore ye must needs be subject, not only for wrath, but for conscience’ sake.”

This settles the divine right of government beyond exception, and that for two ends: first, to terrify evil doers: secondly, to cherish those that do well; which gives government a life beyond corruption, and makes it as durable in the world, as good men shall be. So that government seems to me a part of religion itself, a thing sacred in its institution and end. For, if it does not directly remove the cause, it crushes the effects of evil, and is as such, (though a lower, yet) an emanation of the same Divine Power, that is both author and object of pure religion; the difference lying here, that the one is more free and mental, the other more corporal and compulsive in its operations: but that is only to evil doers; government itself being otherwise as capable of kindness, goodness and charity, as a more private society. They weakly err, that think there is no other use of government, than correction, which is the coarsest part of it: daily experience tells us, that the care and regulation of many other affairs, more soft, and daily necessary, make up much of the greatest part of government; and which must have followed the peopling of the world, had Adam never fell, and will continue among men, on earth, under the highest attainments they may arrive at, by the coming of the blessed Second Adam, the Lord from heaven. Thus much of government in general, as to its rise and end. . . .

Wherefore governments rather depend upon men, than men upon governments. Let men be good, and the government cannot be bad; if it be ill, they will cure it. But, if men be bad, let the government be never so good, they will endeavor to warp and spoil it to their turn. I know some say, let us have good laws, and no matter for the men that execute them: but let them consider, that though good laws do well, good men do better: for good laws may want good men, and be abolished or evaded by ill men; but good men will never want good laws, nor suffer ill ones. It is true, good laws have some awe upon ill ministers, but that is where they have not power to escape or abolish them, and the people are generally wise and good: but a loose and depraved people (which is the question) love laws and an administration like themselves. That, therefore, which makes a good constitution, must keep it, viz: men of wisdom and virtue, qualities, that because they descend not with worldly inheritances, must be carefully propagated by a virtuous education of youth; for which after ages will owe more to the care and prudence of founders, and the successive magistracy, than to their parents, for their private patrimonies. . . .