No related resources

Introduction

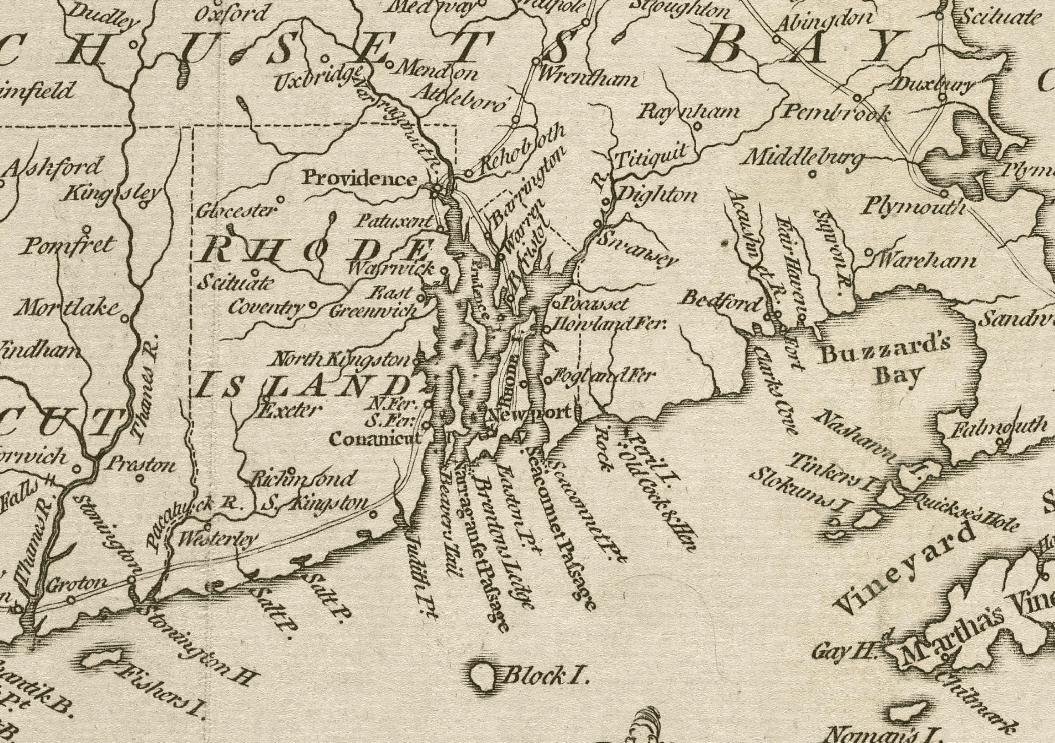

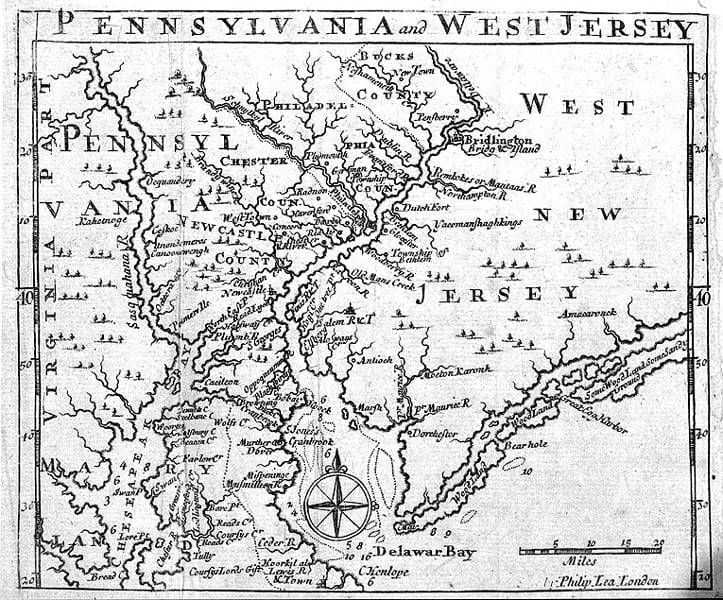

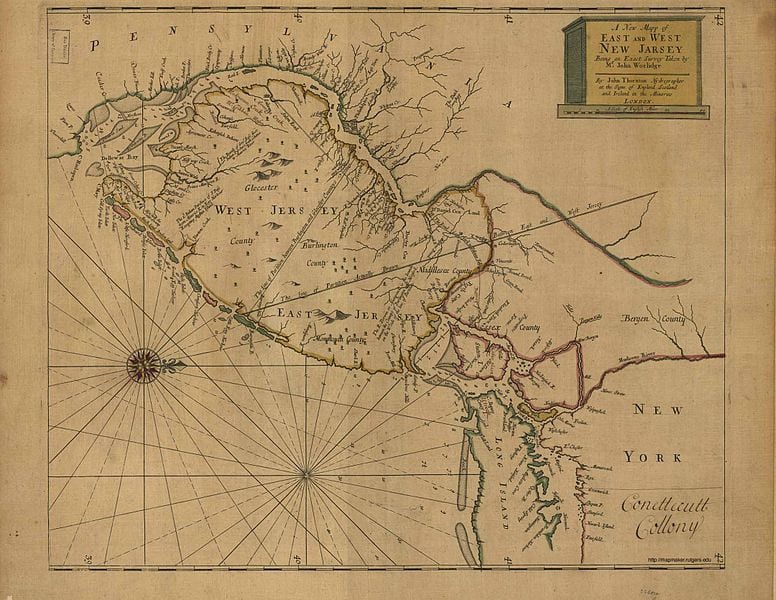

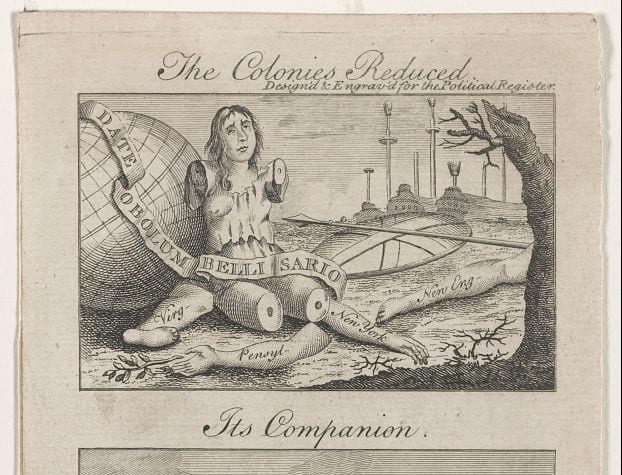

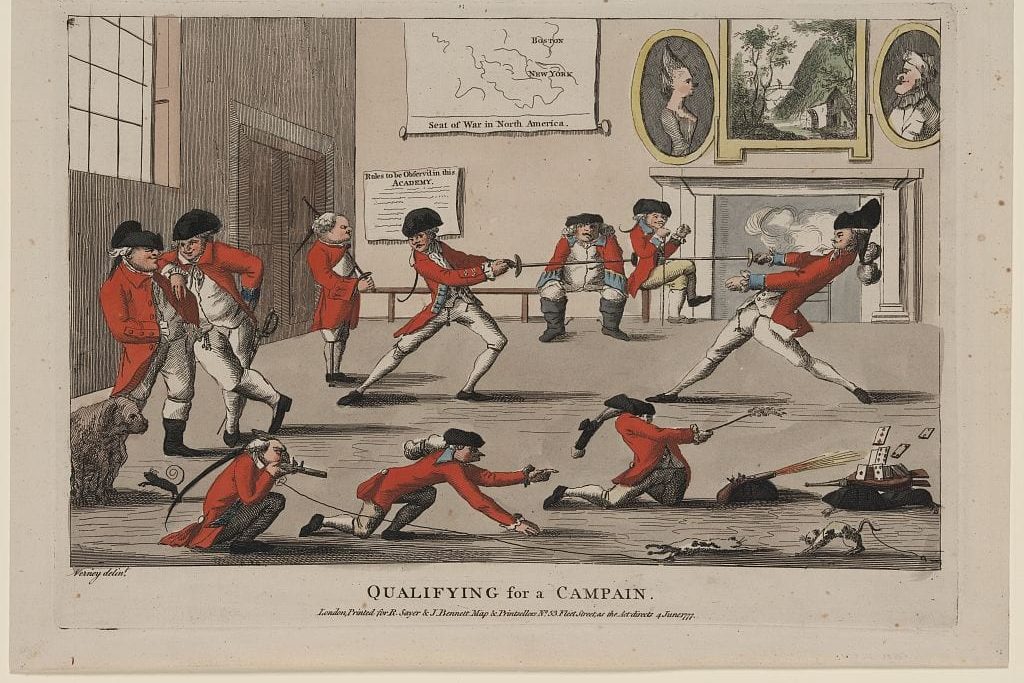

By 1760 the British seemed poised for victory in the French and Indian War. But as the expense of the war weighed on the British treasury, Parliament eyed the North American colonies as a source of revenue. To increase the payment of taxes on imports and curtail rampant smuggling, customs officials sought renewal of their writs of assistance, which authorized them to enter and search individuals’ homes, ships, shops, and warehouses unannounced and without warrants.

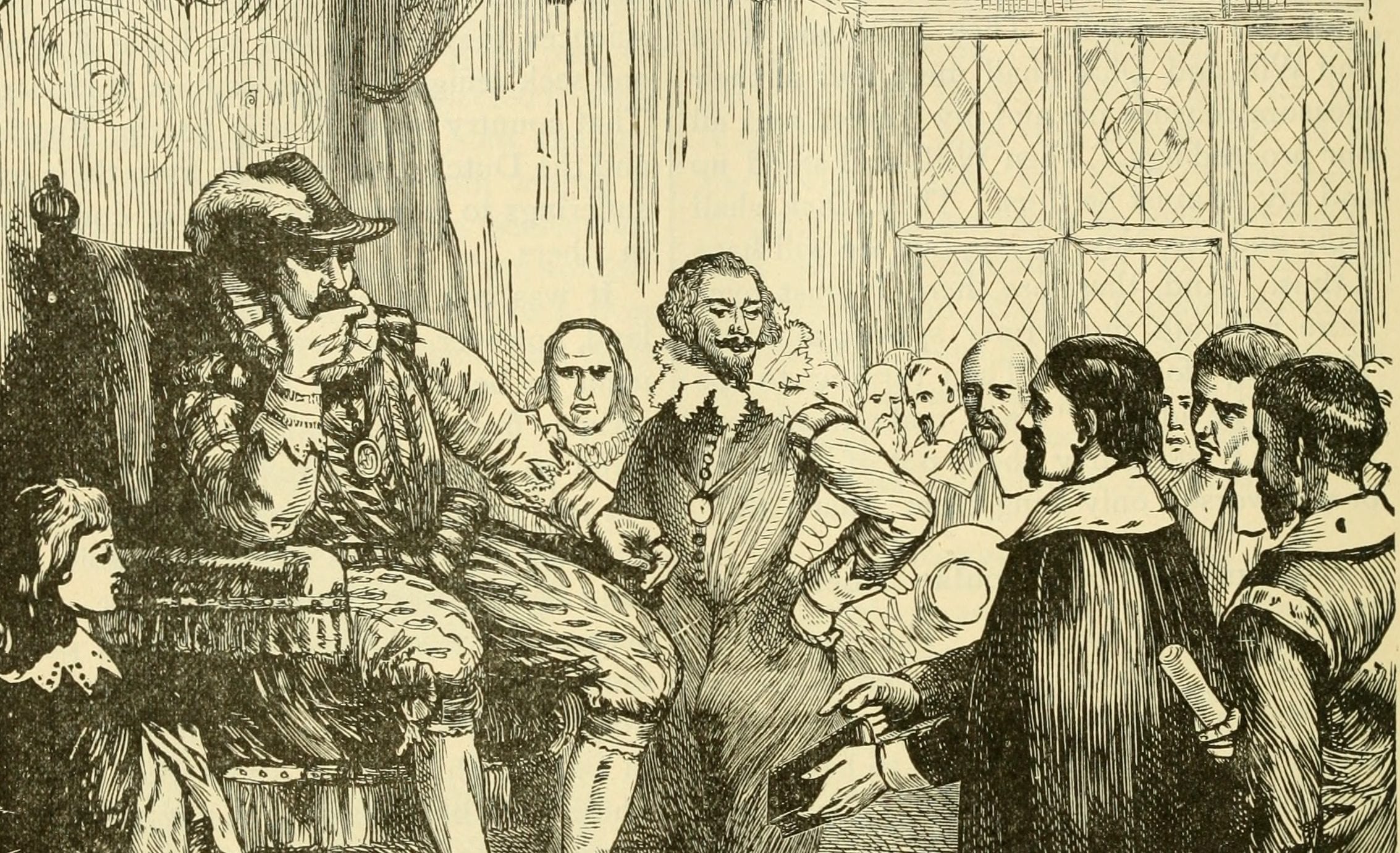

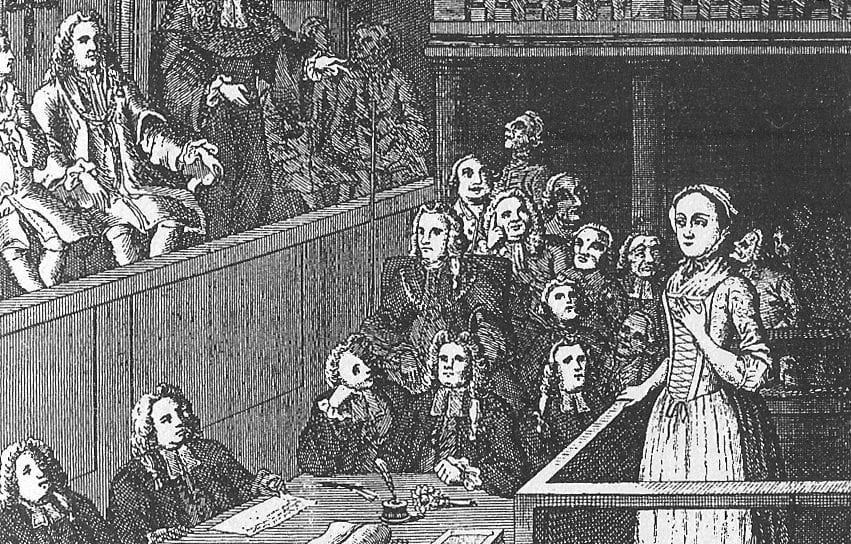

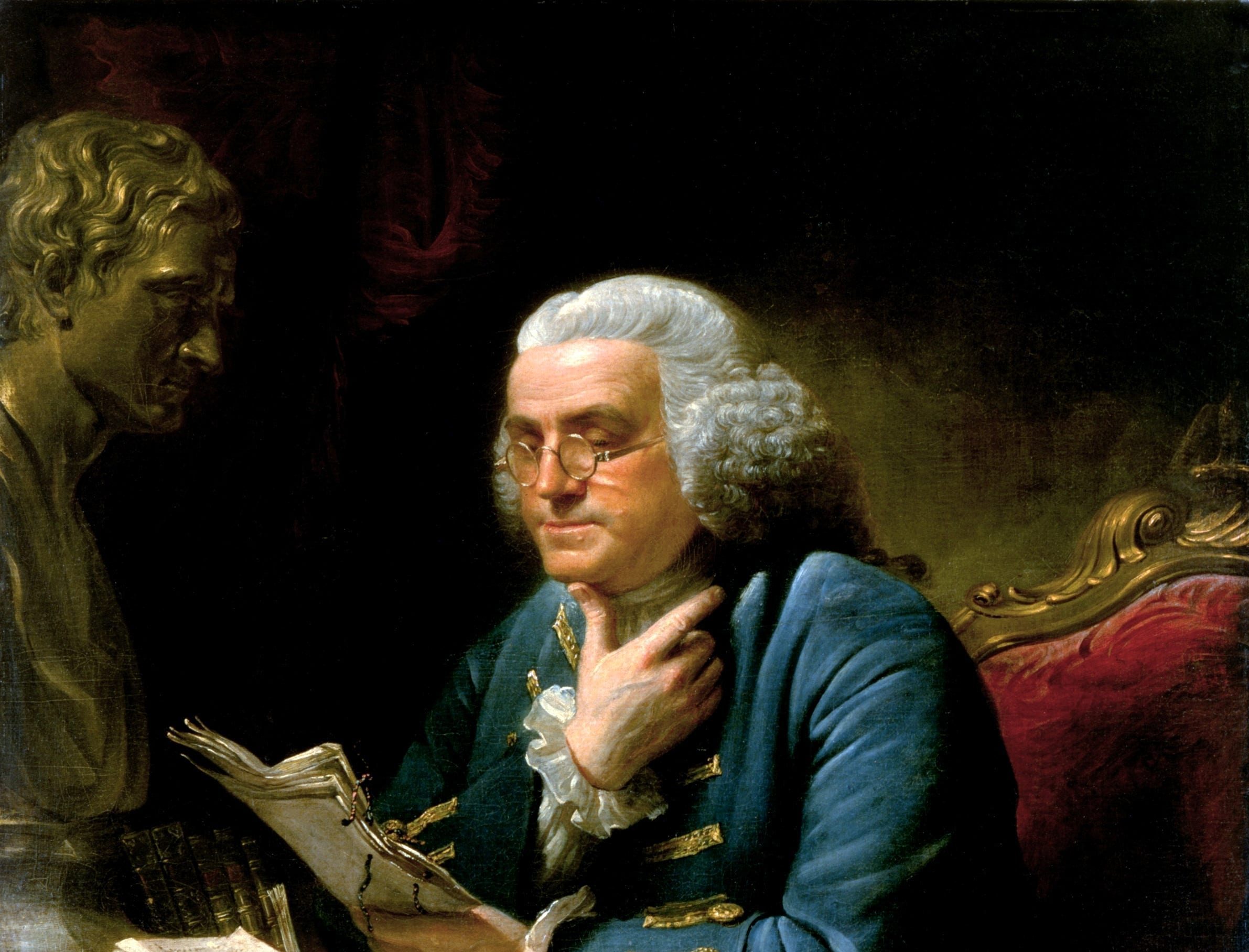

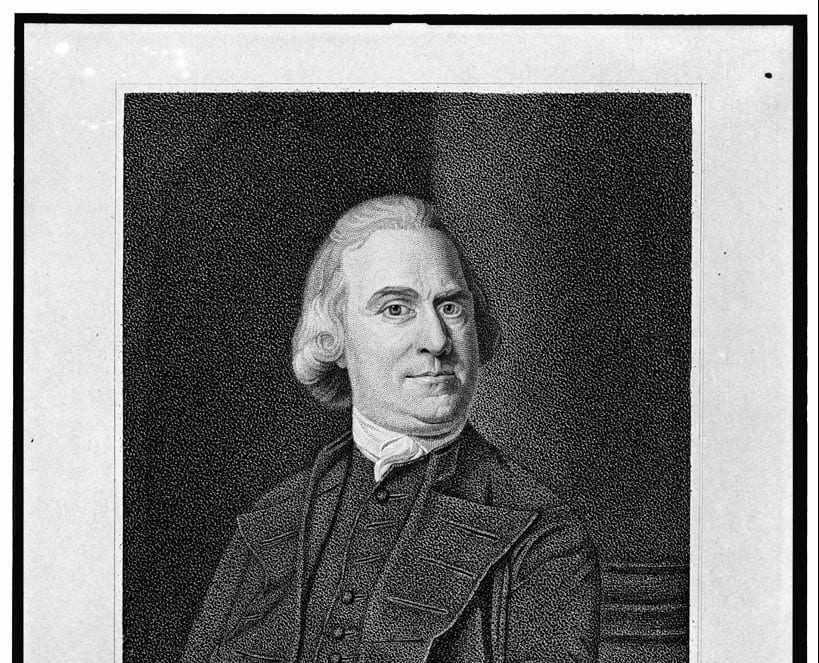

Massachusetts lawyer James Otis (1725––783) so firmly embraced the principle that “a man’s house is his castle” that he resigned as his colony’s Admiralty Court advocate general when pressed to defend the writs of assistance. Considering them a violation of “one of the most essential branches of English liberty,” he served as attorney for a group of merchants challenging the writs. In a case heard by the Massachusetts Superior Court, Otis spoke for nearly five hours. John Adams, who was in the audience, took notes on Otis’s remarks.

Although Otis lost the case, his passionate opposition to the writs launched his career as a leading critic of British imperial policy. In May 1761, Bostonians elected him to represent them in the legislature. He helped orchestrate resistance to the 1765 Stamp Act and 1767 Townshend Acts. In 1769, however, a tax collector clubbed him in the head during a barroom brawl, prompting (or exacerbating) a mental illness that continued until 1783, when he was struck by lightning and died. Adams considered Otis a great patriot, perhaps “the greatest orator” of his era, and “a man whom none who ever knew him, can ever forget.”

Source: John Adams’s Reconstruction of Otis’s Speech in the Writs of Assistance Case, in The Collected Political Writings of James Otis, ed. Richard A. Samuelson (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2015), 11–4. http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2703

MAY IT PLEASE YOUR HONORS,

I was desired by one of the Court to look into the books, and consider the question now before them concerning writs of assistance. I have accordingly considered it, and now appear, not only in obedience to your order, but likewise in behalf of the inhabitants of this town, who have presented another petition, and out of regard to the liberties of the subject. And I take this opportunity to declare, that whether under a fee or not (for in such a cause as this I despise a fee) I will to my dying day oppose with all the powers and faculties God has given me, all such instruments of slavery on the one hand, and villainy on the other, as this writ of assistance is.

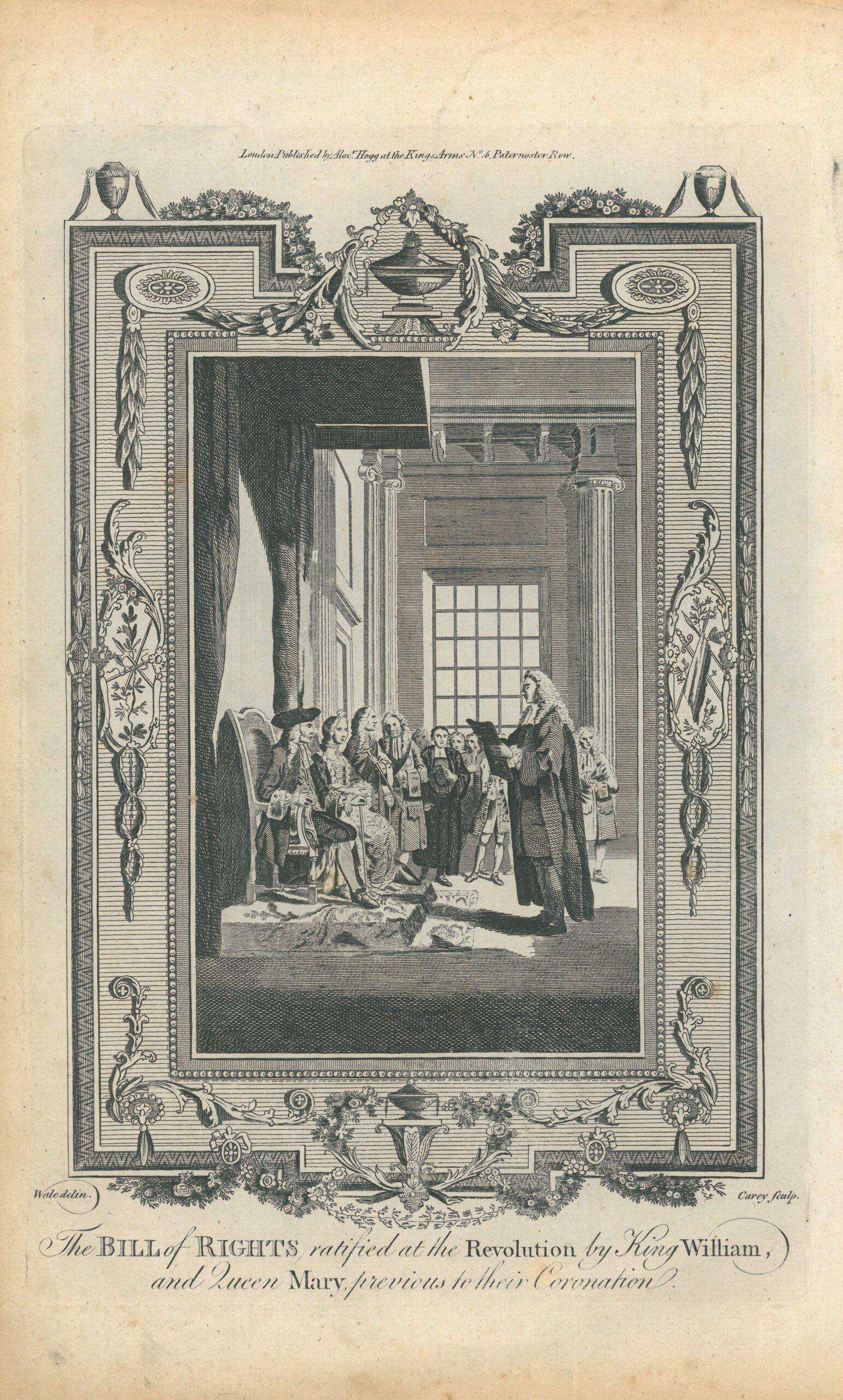

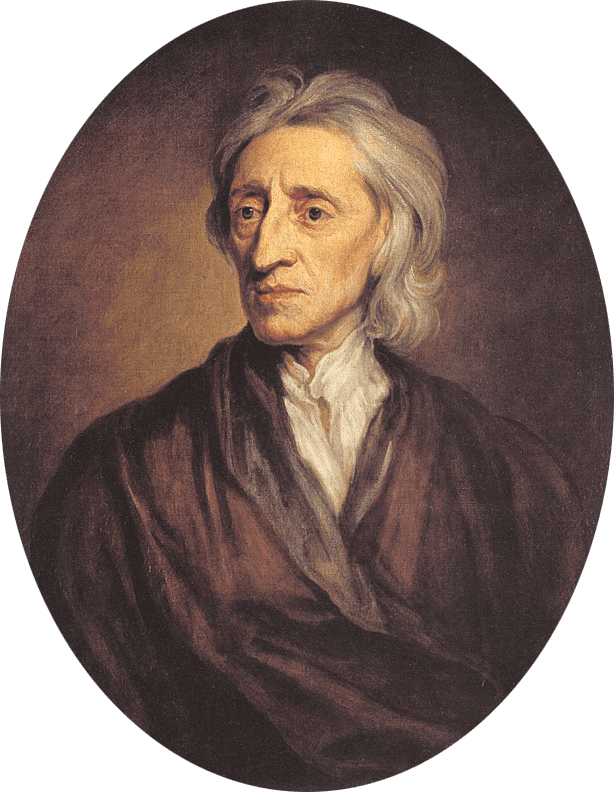

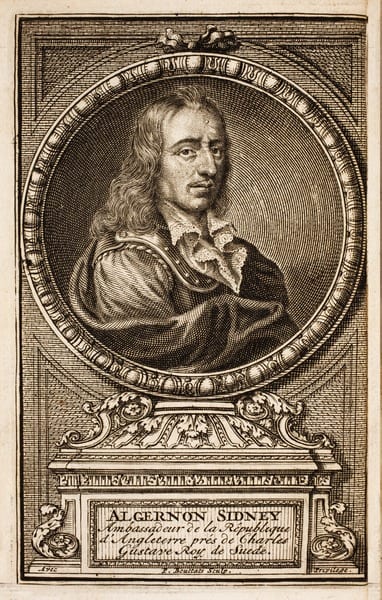

It appears to me the worst instrument of arbitrary power, the most destructive of English liberty and the fundamental principles of law, that ever was found in an English law book. I must, therefore, beg your honors’ patience and attention to the whole range of an argument, that may perhaps appear uncommon in many things, as well as to points of learning that are more remote and unusual; that the whole tendency of my design may the more easily be perceived, the conclusions better discerned, and the force of them be better felt. I shall not think much of my pains in this cause, as I engaged in it from principle. I was solicited to argue this cause as advocate general; and because I would not, I have been charged with desertion from my office. To this charge I can give a very sufficient answer. I renounced that office, and I argue this cause, from the same principle; and I argue it with the greater pleasure, as it is in favor of British liberty, at a time when we hear the greatest monarch upon earth declaring from his throne that he glories in the name of Briton, and that the privileges of his people are dearer to him than the most valuable prerogatives of his crown; and as it is in opposition to a kind of power, the exercise of which, in former periods of English history, cost one king of England his head,[1] and another his throne.[2] I have taken more pains in this cause, than I ever will take again, although my engaging in this and another popular cause has raised much resentment. But I think I can sincerely declare, that I cheerfully submit myself to every odious name for conscience’s sake; and from my soul I despise all those, whose guilt, malice, or folly has made them my foes. Let the consequences be what they will, I am determined to proceed. The only principles of public conduct, that are worthy of a gentleman or a man, are to sacrifice estate, ease, health, and applause, and even life to the sacred calls of his country. These manly sentiments, in private life, make the good citizen; in public life, the patriot and the hero. I do not say, that when brought to the test, I shall be invincible. I pray God I may never be brought to the melancholy trial; but if ever I should, it will be then known how far I can reduce to practice principles, which I know to be founded in truth. In the mean time I will proceed to the subject of this writ.

In the first place, may it please your honors, I will admit that writs of one kind may be legal; that is, special writs, directed to special officers, and to search certain houses, etc., specially set forth in the writ, may be granted by the Court of Exchequer at home, upon oath made before the lord treasurer by the person who asks it, that he suspects such goods to be concealed in those very places he desires to search. The act of 14 Charles II, which Mr. Gridley[3] mentions, proves this. And in this light the writ appears like a warrant from a Justice of the Peace to search for stolen goods. Your honors will find in the old books concerning the office of a justice of the peace, precedents of general warrants to search suspected houses. But in more modern books you will find only special warrants to search such and such houses specially named, in which the complainant has before sworn that he suspects his goods are concealed; and you will find it adjudged that special warrants only are legal. In the same manner I rely on it, that the writ prayed for in this petition, being general, is illegal. It is a power that places the liberty of every man in the hands of every petty officer. I say I admit that special writs of assistance, to search special places, may be granted to certain person on oath; but I deny that the writ now prayed for can be granted, for I beg leave to make some observations on the writ itself, before I proceed to other acts of Parliament. In the first place, the writ is universal, being directed “to all and singular Justices, Sheriffs, Constables, and all other officers and subjects”; so, that, in short, it is directed to every subject in the king’s dominions. Everyone with this writ may be a tyrant; if this commission be legal, a tyrant in a legal manner also may control, imprison, or murder anyone within the realm. In the next place, it is perpetual; there is no return. A man is accountable to no person for his doings. Every man may reign secure in his petty tyranny, and spread terror and desolation around him. In the third place, a person with this writ, in the daytime, may enter all houses, shops, etc., at will, and command all to assist him. Fourthly, by this writ not only deputies, etc., but even their menial servants, are allowed to lord it over us. Now one of the most essential branches of English liberty is the freedom of one’s house. A man’s house is his castle; and while he is quiet, he is as well guarded as a prince in his castle. This writ, if it should be declared legal, would totally annihilate this privilege. Custom-house officers may enter our houses, when they please; we are commanded to permit their entry. Their menial servants may enter, may break locks, bars, and everything in their way; and whether they break through malice or revenge, no man, no court, can inquire. Bare suspicion without oath is sufficient. This wanton exercise of this power is not a chimerical suggestion of a heated brain. I will mention some facts. Mr. Pue[4] had one of these writs, and when Mr. Ware[5] succeeded him, he endorsed this writ over to Mr. Ware; so that these writs are negotiable from one officer to another; and so your Honors have no opportunity of judging the person to whom this vast power is delegated. Another instance is this: Mr. Justice Walley[6] had called this same Mr. Ware before him, by a constable, to answer for a breach of Sabbath-day acts, or that of profane swearing. As soon as he had finished, Mr. Ware asked him if he had done. He replied, Yes. Well then, said Mr. Ware, I will show you a little of my power. I command you to permit me to search your house for uncustomed goods.[7] And [Ware] went on to search his house from the garret to the cellar; and then served the constable in the same manner. But to show another absurdity in this writ; if it should be established, I insist upon it, every person by the 14 Charles II has this power as well as custom-house officers. The words are, “It shall be lawful for any person or persons authorized,” etc. What a scene does this open! Every man, prompted by revenge, ill humor, or wantonness, to inspect the inside of his neighbor’s house, may get a writ of assistance. Others will ask it from self-defence; one arbitrary exertion will provoke another, until society be involved in tumult and in blood.

Again, these writs are not returned. Writs in their nature are temporary things. When the purposes for which they are issued are answered, they exist no more; but these live forever; no one can be called to account. Thus reason and the constitution are both against this writ. Let us see what authority there is for it. Not more than one instance can be found of it in all our law books; and that was in the zenith of arbitrary power namely in the reign of Charles II, when star-chamber powers were pushed to extremity by some ignorant clerk of the exchequer. But had this writ been in any book whatever, it would have been illegal. All precedents are under the control of the principles of law. Lord Talbot says it is better to observe these than any precedents, though in the House of Lords, the last resort of the subject. No acts of Parliament can establish such a writ; though it should be made in the very words of the petition, it would be void. An act against the constitution is void…. But these prove no more than what I before observed, that special writs may be granted on oath and probable suspicion. The act of 7 and 8 William III that the officers of the plantations shall have the same powers, etc., is confined to this sense; that an officer should show probable ground; should take his oath of it; should do this before a magistrate; and that such magistrate, if he think proper, should issue a special warrant to a constable to search the places.

- 1. Charles I (1600–1649) served as king from 1625 until his execution in 1649.

- 2. James II (1633–1701) served as king from 1685 until his ouster during the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

- 3. Massachusetts lawyer Jeremiah Gridley (1702–1767) represented the government in this case.

- 4. Jonathan Pue (died 1760) served as surveyor of customs for the Port of Salem.

- 5. Nathaniel Ware (died 1767) served as comptroller of customs from 1750 to 1764 for the Port of Boston.

- 6. Abiel Walley (1710–1759) in 1740 became justice of the quorum of Suffolk County, Massachusetts.

- 7. Uncustomed: not having passed through customs; smuggled.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.