No study questions

No related resources

Introduction

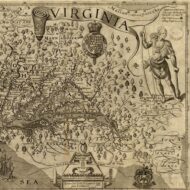

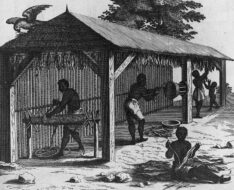

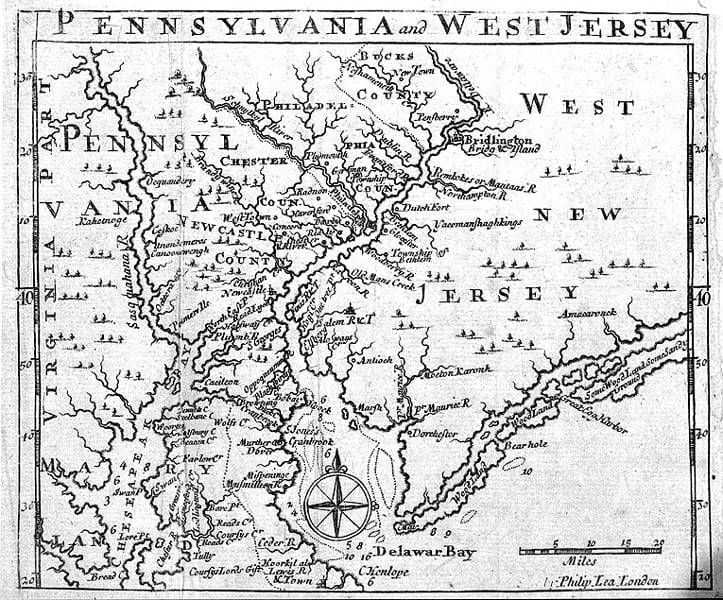

When the Virginia colony was founded in 1607, the majority of unfree laborers in the colony were indentured servants, men and women who signed a legal contract called an indenture that bound them to work for a certain individual for a certain number of years, in exchange for which they received room, board, and some type of education or training. During their indenture, the servant was legally subject to the rule of their master; although there were laws to protect servants, Virginia’s spread-out settlements meant that working conditions in actuality varied widely. No matter how oppressive their master, however, at the end of their indenture period, the individual servant was free to leave (usually with a set of supplies and a sum of money adequate for starting out on his or her own way in the world).

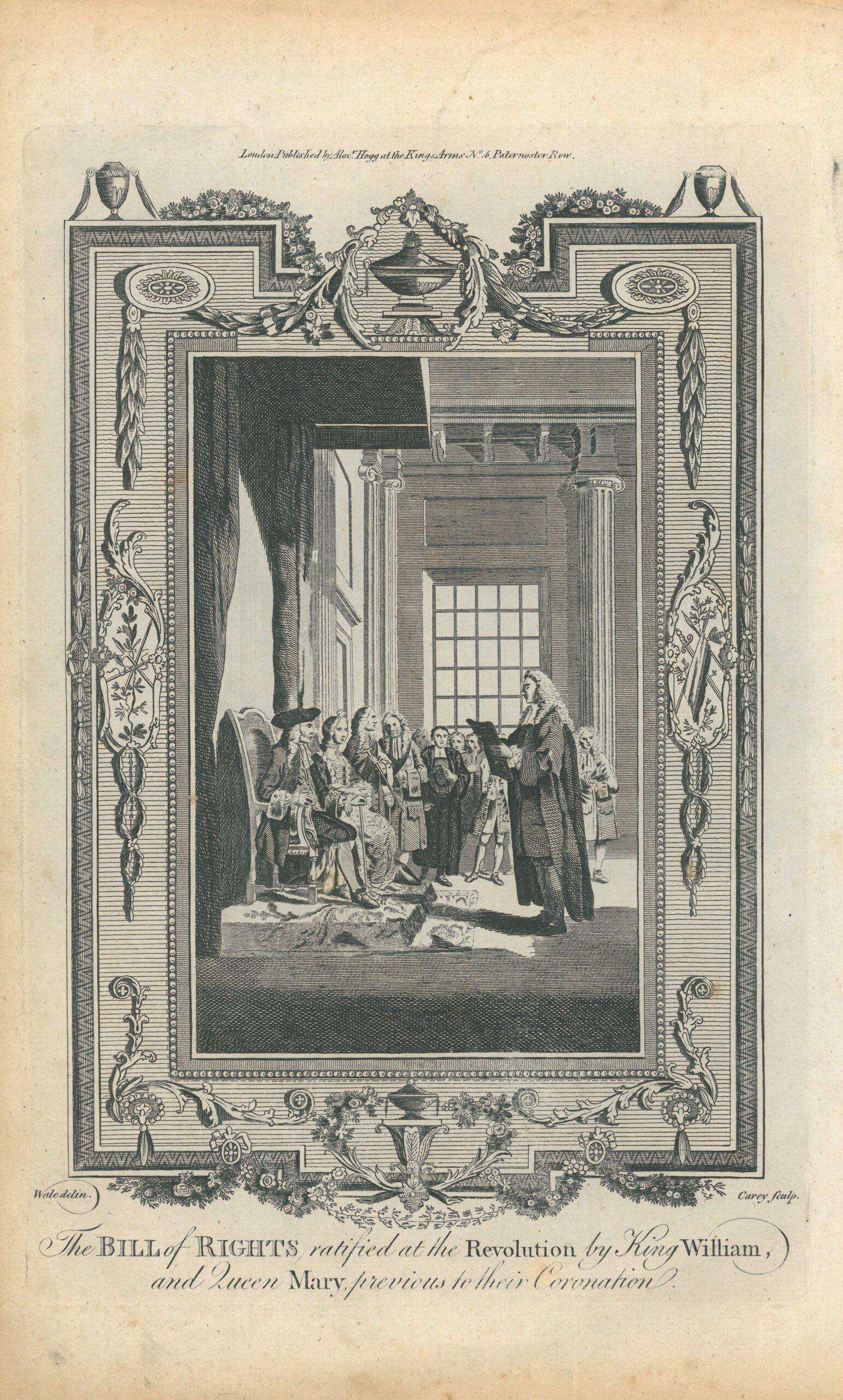

The second class of unfree labor consisted of slaves. At the beginning of the colonial period, records indicate that the most significant difference between slavery and indentured servitude lay in the expectation that, in the latter case, the individual would receive the sort of training and tools necessary to eventually take their place as a free person. In the early seventeenth century, race-based slavery for life did not exist in the Anglo-American world. Instead, where it existed, slavery was linked to the cultural and religious background of the enslaved person: non-Christian captives taken in a war, for example, might be enslaved, but not Christians, regardless of their racial or ethnic background. Nor was slavery always a permanent and inheritable condition: in the early years of the colony, individual slaves were able to win their freedom by demonstrating proof of their conversion to Christianity; in addition, enslaved persons were sometimes able to arrange to purchase their freedom, and policies regarding the status of children born to enslaved persons remained in flux until the mid-seventeenth century.

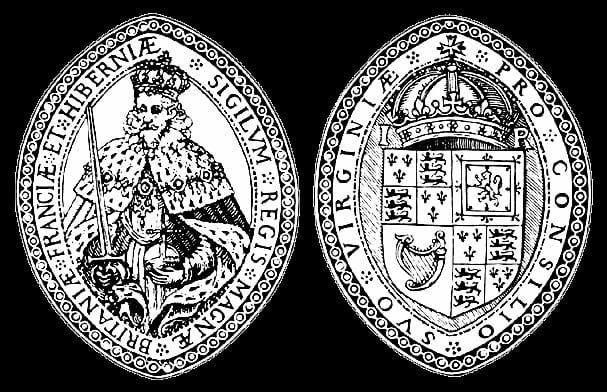

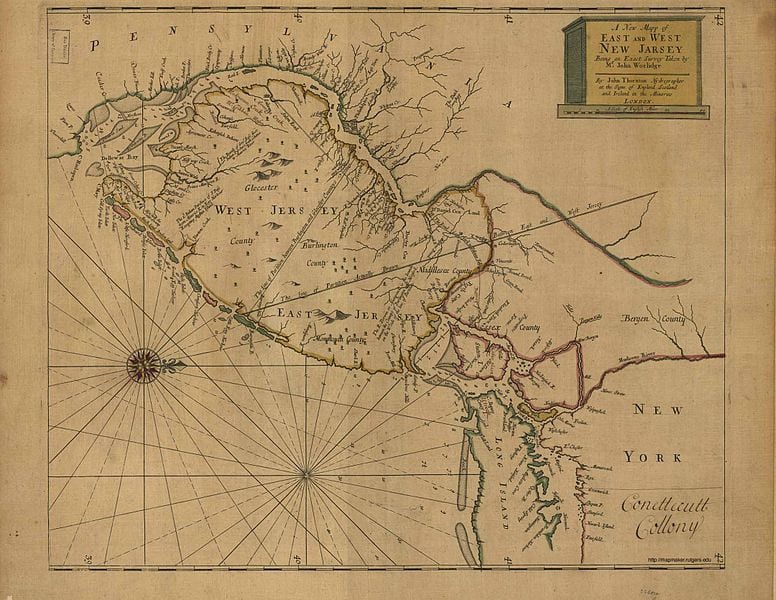

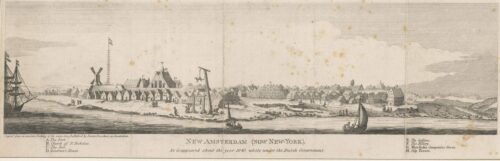

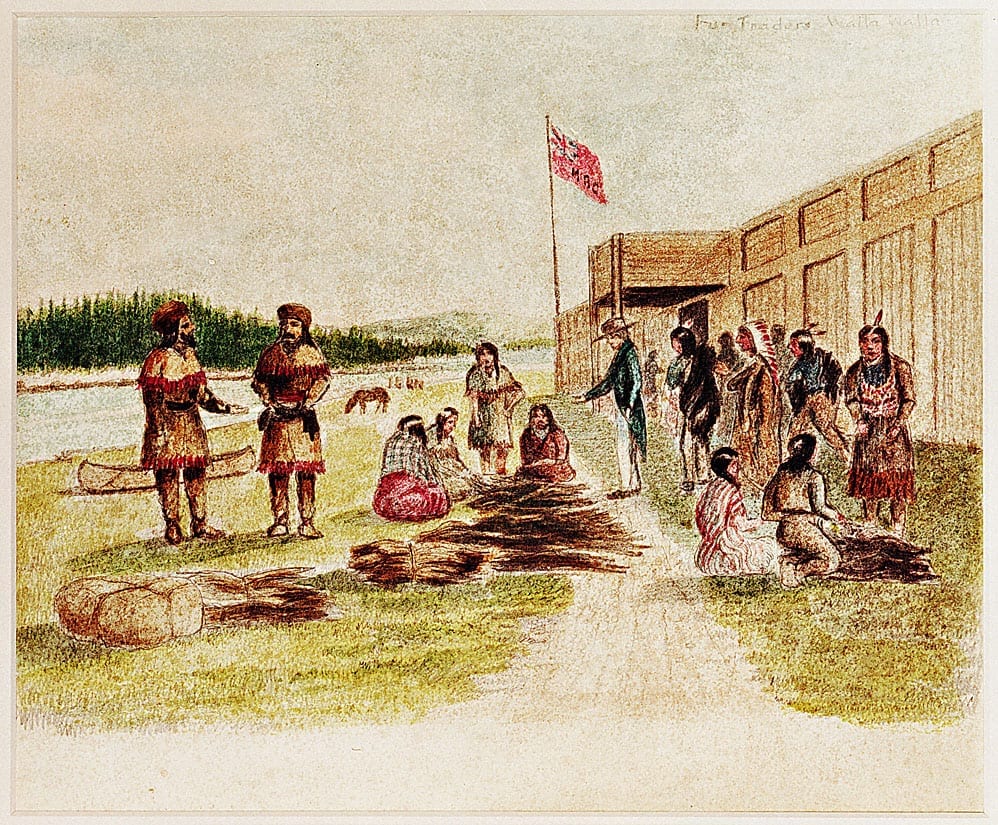

From the beginning, both forms of unfree labor coexisted in Virginia: the funders of the colony relied upon a mix of incentives (free land in exchange for a period of labor) and the bad economy in England to encourage laborers to come to the new colony as indentured servants, while the colonists took captives as slave hostages during their frequent conflicts with the local native population. The first slaves from Africa arrived at Jamestown in 1619.

Initially, the majority of the colony’s labor force consisted of indentured servants, but over time, as the English expanded their participation in the Atlantic and Indian slave trades and market conditions in the mother country improved, the balance shifted. By the end of the 1670s, black slaves began to replace both white indentured servants and Indian slaves as Virginians’ primary source of labor.

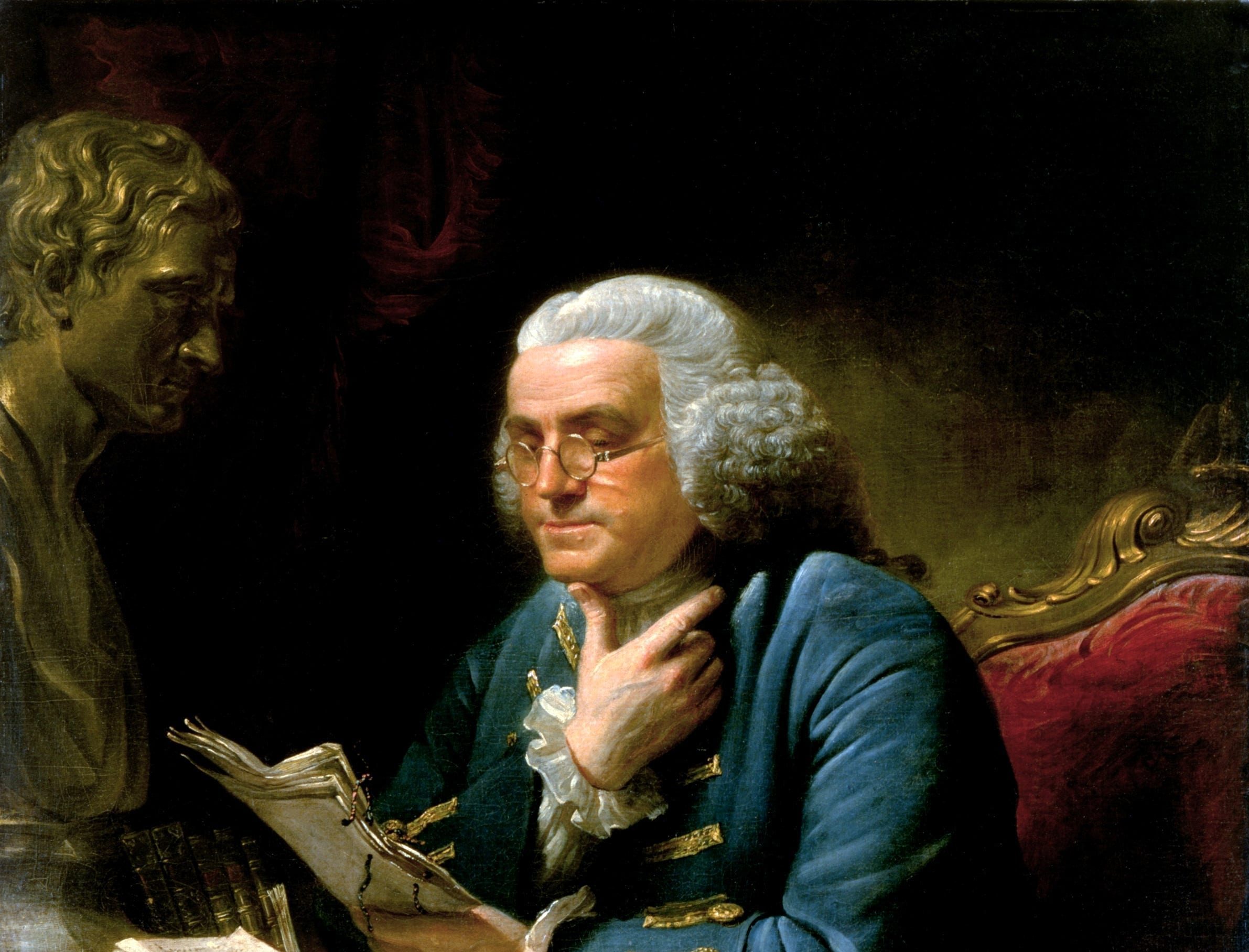

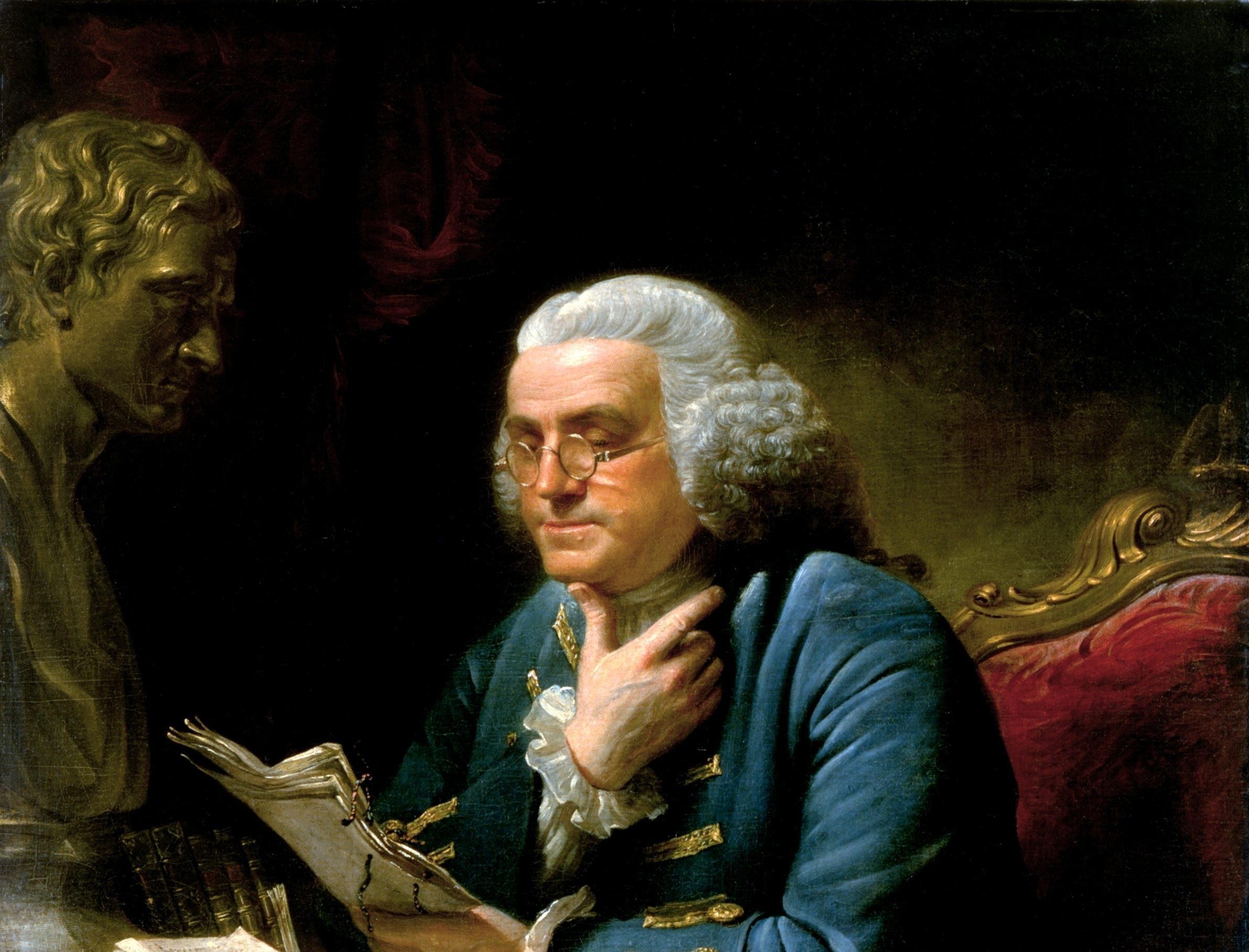

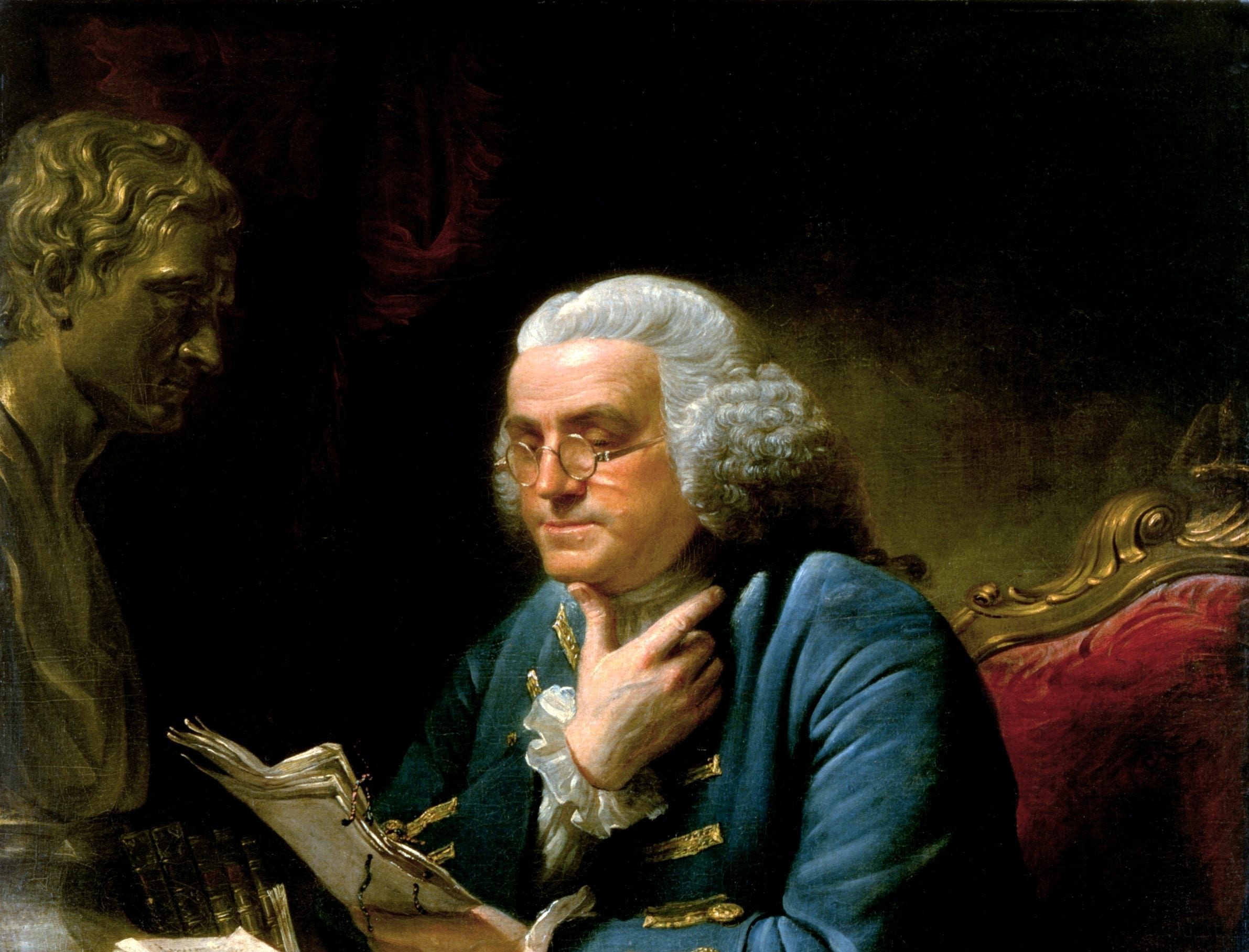

George Alsop, A Character of the Province of Maryland (1666) ed. Newton D. Mereness (Cleveland: The Burrows Brothers Company, 1902), 52–61. George Alsop (c. 1636 – c. 1673), was a supporter of Charles I during the English Civil War (1642–1651), emigrated to Maryland following Charles’ defeat.

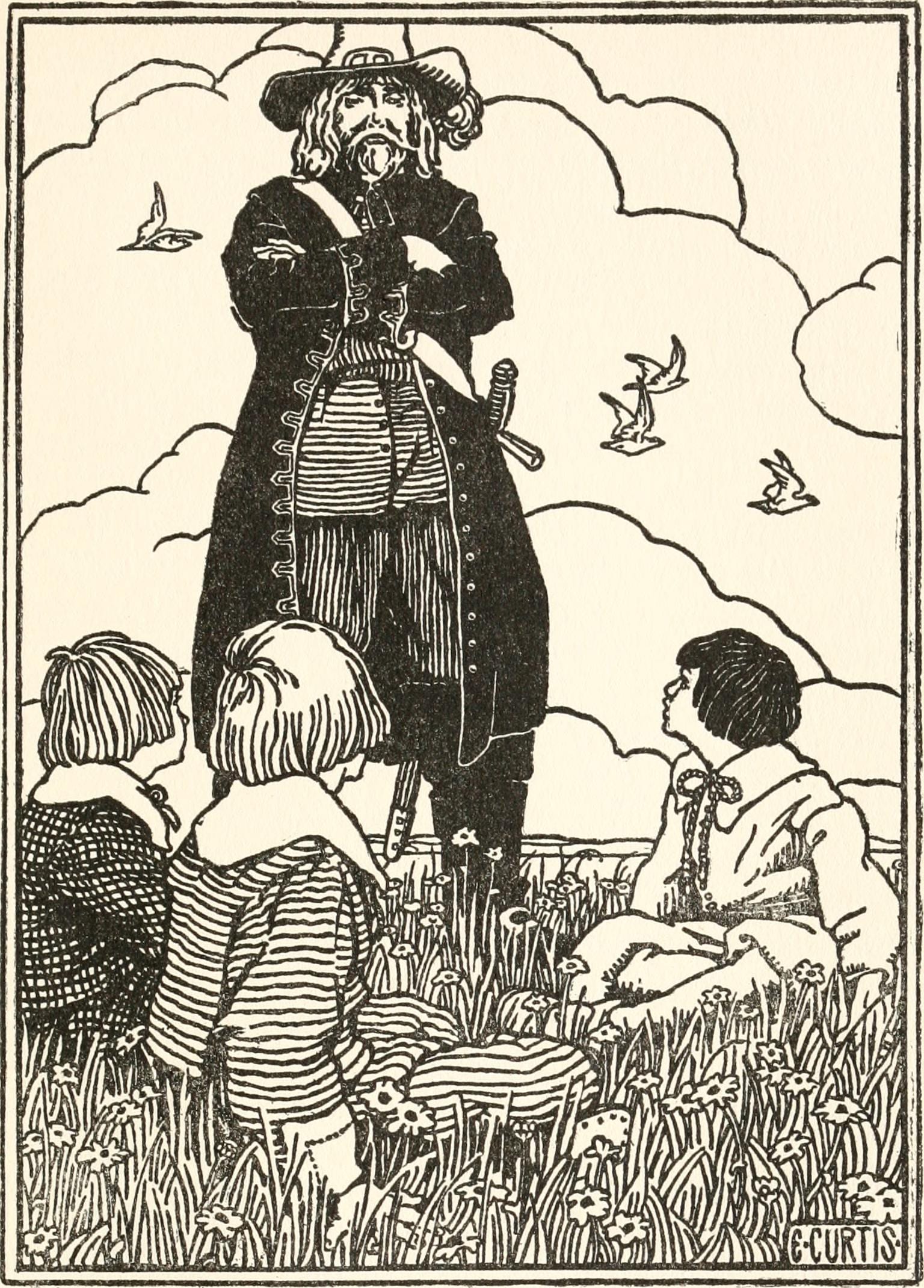

The necessariness of Servitude proved, with the common usage of Servants in Mary-Land, together with their Privileges

As there can be no monarchy without the supremacy of a king and crown, nor no king without subjects, nor any parents without it be by the fruitful off-spring of children; neither can there be any masters, unless it be by the inferior servitude of those that dwell under them, by a commanding enjoyment: And since it is ordained from the original and superabounding wisdom of all things, that there should be degrees and diversities amongst the sons of men, in acknowledging of a superiority from inferiors to superiors; the servant with a reverent and befitting obedience is as liable to this duty in a measurable performance to him whom he serves, as the loyalest of subjects to his prince. Then since it is a common and ordained fate, that there must be servants as well as masters, and that good servitudes are those colleges of sobriety that checks in the giddy and wild-headed youth from his profuse and uneven course of life, by a limited constrainment, as well as it otherwise agrees with the moderate and discreet servant: Why should there be such an exclusive obstacle in the minds and unreasonable dispositions of many people, against the limited time of convenient and necessary servitude, when it is a thing so requisite, that the best of kingdoms would be unhinged from their quiet and well settled Government without it. . . .

Why then, if servitude be so necessary that no place can be governed in order, nor people live without it, this may serve to tell those which prick up their ears and bray against it, that they are none but asses, and deserve the bridle of a strict commanding power to rein them in: For I’m certainly confident, that there are several thousands in most kingdoms of Christendom, that could not at all live and subsist, unless they had served some prefixed time, to learn either some trade, art, or science, and by either of them to extract their present livelihood.

. . .

Then let such, where Providence hath ordained to live as servants, either in England or beyond Sea, endure the prefixed yoke of their limited time with patience, and then in a small computation of years, by an industrious endeavour, they may become masters and mistresses of families themselves. And let this be spoke to the deserved praise of Mary-Land, that the four years I served there were not to me so slavish, as a two years Servitude of a Handicraft Apprenticeship was here in London. . . .

They whose abilities cannot extend to purchase their own transportation over into Mary-Land, (and surely he that cannot command so small a sum for so great a matter, his life must needs be mighty low and dejected) I say they may for the debarment of a four years sordid liberty, go over into this Province and there live plenteously well. And what’s a four year’s servitude to advantage a man all the remainder of his days, making his predecessors happy in his sufficient abilities, which he attained to partly by the restrainment of so small a time?

Now those that commit themselves unto the care of the merchant to carry them over, they need not trouble themselves with any inquisitive search touching their voyage; for there is such an honest care and provision made for them all the time they remain aboard the ship, and are sailing over, that they want for nothing that is necessary and convenient.

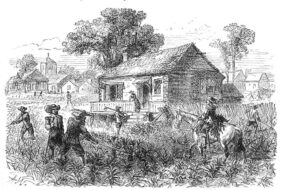

The merchant commonly before they go aboard the ship, or set themselves in any forwardness for their voyage, has conditions of agreements drawn between him and those that by a voluntary consent become his servants, to serve him, his heirs or assigns, according as they in their primitive acquaintance have made their bargain, some two, some three, some four years and whatever the master or servant ties himself up to here in England by condition, the laws of the province will force a performance of when they come there: Yet here is this privilege in it when they arrive, If they dwell not with the Merchant they made their first agreement withall, they may choose, whom they will serve their prefixed time with; and after their curiosity has pitched on one whom they think fit for their turn, and that they may live well withall, the Merchant makes an Assignment of the Indenture over to him whom they of their free will have chosen to be their Master, in the same nature as we here in England (and no otherwise) turn over Covenant Servants or Apprentices from one Master to another. . . . The Servants here in Mary-Land of all colonies, distant or remote plantations, have the least cause to complain, either for strictness of servitude, want of provisions, or need of apparel: five days and a half in the summer weeks is the allotted time that they work in; and for two months, when the sun predominates in the highest pitch of his heat, they claim an ancient and customary privilege, to repose themselves three hours in the day within the house, and this is undeniably granted to them that work in the Fields.

In the Winter time, which lasteth three months (viz.) December, January, and February, they do little or no work or employment, save cutting of wood to make good fires to sit by, unless their ingenuity will prompt them to hunt the deer, or boar, or recreate themselves in fowling, to slaughter the swans, geese, and turkeys (which this country affords in a most plentiful manner:) For every servant has a gun, powder and shot allowed him, to sport him withal on all holidays and leisurable times, if he be capable of using it, or be willing to learn.

Now those servants which come over into this province, being artificers, they never (during their servitude) work in the fields, or do any other employment save that which their handicraft and mechanic endeavors are capable of putting them upon, and are esteemed as well by their masters, as those that employ them, above measure. He that’s a tradesman here in Mary-Land (though a Servant), lives as well as most common handicrafts do in London, though they may want something of that liberty which freemen have, to go and come at their pleasure. . . . He that lives in the nature of a servant in this province, must serve but four years by the custom of the country; and when the expiration of his time speaks him a freeman, there’s a law in the Province, that enjoins his master whom he hath served to give him fifty acres of land, corn to serve him a whole year, three suites of apparel, with things necessary to them, and tools to work withal; so that they are no sooner free, but they are ready to set up for themselves, and when once entered, they live passingly well.

The women that go over into this province as servants, have the best luck here as in any place of the world besides; for they are no sooner on shore, but they are courted into a copulative matrimony, which some of them (for aught I know) had they not come to such a market with their virginity, might have kept it by them until it had been mouldy, unless they had to let it out by a yearly rent to some of the Inhabitants of Lewknors-lane [a disreputable neighborhood in London] . . . Men have not altogether so good luck as women in this kind, or natural preferment, without they be good rhetoricians, and well versed in the art of persuasion then (probably) they may rivet themselves in the time of their servitude into the private and reserved favor of their mistress, if age speak their master deficient.

In short, touching the Servants of this Province, they live well in the time of their Service, and by their restrainment in that time, they are made capable of living much better when they come to be free; which in several other parts of the world I have observed, that after some servants have brought their indented and limited time to a just and legal period by Servitude, they have been much more incapable of supporting themselves from sinking into the Gulf of a slavish, poor, fettered, and intangled life, then all the fastness of their prefixed time did involve them in before.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.