Introduction

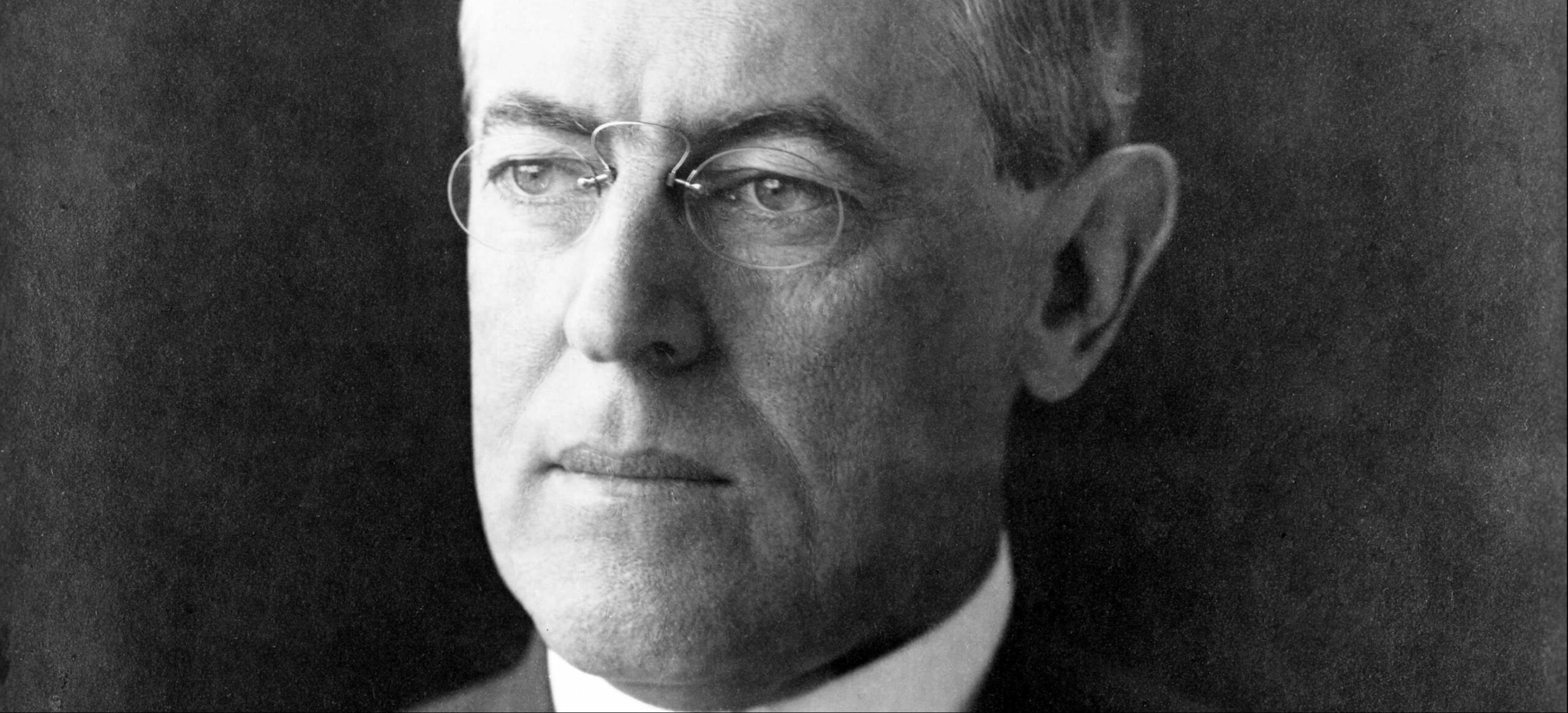

Carl L. Becker (1873–1945) was a prominent American historian and the author of many scholarly works on political and intellectual history, among them several books on the American Revolution and the political philosophy of the eighteenth century. A student of historian James Harvey Robinson, Becker is often associated with the New History movement. Closely allied with the rise of progressivism in academic and political circles, the New History sought to understand human history as the unfolding of social, scientific, and intellectual progress. Under this rubric, academics endeavored to connect the professional study of history to current political problems and reform.

Becker became relatively well known in academic circles for his historical relativism—that is, the idea that all so-called truths are merely historically relative concepts embraced by people of a certain time and place. Becker argued that contemporary philosophy and social science understood that there are no transhistorical truths that apply to all human beings across time and place, everywhere and always. The following excerpt, taken from Becker’s 1922 book on the Declaration of Independence, applied this thought to the idea of natural rights. According to Becker, beginning in the nineteenth century, contemporary observers had gained historical insight. They knew that to ask whether the natural rights principles of the Declaration are true or false was “essentially a meaningless question.” Becker’s argument here was representative of the progressive critique of the first principles of the American founding. Included below is also a selection from the 1942 reprint of Becker’s book, where he reconsidered this thesis in light of the rise of Nazism in Europe.

Source: Carl L. Becker, The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1922), 273–79, available at The Online Library of Liberty: https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/becker-the-declaration-of-independence-a-study-on-the-history-of-political-ideas.

Natural rights in the eighteenth-century sense, in the sense of the Declaration of Independence, could not be a possession of the individual who was thus securely imprisoned in the social process. Rights he still did possess, rights that were even “natural” and God-given in their way; but they were not something to be fought for and won. Since the rights which God and nature gave him were little more than the privileges, or absence of privileges, which the positive law conferred, it was indeed not always easy to tell the difference between rights and wrongs. Perhaps there was consolation in thinking that one’s rights or wrongs, such as they were, were useful to that “society” which “shapes man for its own purposes”; and so long as the individual could be sure the purpose was beneficent, and would benefit someone in the long run, he might be content to sacrifice himself for the ultimate good which God could see even if he himself could not. But if the social process should some time cease to be visualized as the progressive realization of God’s purpose, the individual was likely to find his prison rather stuffy, might even find it impossible to associate the idea of rights in any sense with conditions that had every appearance of being ugly and meaningless.

This in some measure came to pass in the latter nineteenth century. Much serious, minutely critical investigation into the origins of institutions seemed to show that all things human might be fully accounted for without recourse to God or the Transcendent Idea. At the same time the fruitful discoveries of natural science, particularly the great discovery of Darwin, were convincing the learned world that the origin, differentiation, and modification of all forms of life on the globe were the result of natural forces in a material sense; and that the operation of these forces might be formulated in terms of abstract laws which would neatly and sufficiently account for the organic world, just as the physical sciences were able to account for the physical world. When so much the greater part of the universe showed itself amenable to the reign of a purely material natural law, it was difficult to suppose that man (a creature in many respects astonishingly like the higher forms of apes) could have been permitted to live under a special dispensation. It was much simpler to assume one origin for all life and one law for all growth; simpler to assume that man was only the most highly organized of the creatures (the missing link would doubtless shortly be found), and to think of his history accordingly, as only a more subtly negotiated struggle for existence and survival.

Meanwhile, this view seemed to find striking confirmation in the world of affairs. “The most indifferent arguments are good when one has a majority of bayonets,” Bismarck assured his contemporaries; and contemporaries celebrated his work when he made the German Empire by “iron and blood.”. . . Industrial exploitation, Machiavellian politics, war—what were these, what had they ever been, but nature’s instruments for enabling those to survive who had the power?[1]

In this view of things, neither God nor the Transcendent Idea seemed any longer a necessary part of the social process. The social process would go on very well by itself. But what its purpose was, or whether it would ever come to any good end, who could say? . . . In a universe in which man seemed only a chance deposit on the surface of the world, and the social process no more than a resolution of blind force, the “right” and the “fact” were indeed indistinguishable; in such a universe the rights which nature gave to man were easily thought of as measured by the power he could exert. Aggressive nationalism found this idea convenient for the exploitation of backward races; while militant socialists, proclaiming anew the social revolution, and giving but a passing glance at the old revolutionary doctrine of the Declaration of Independence and the [French] Declaration of the Rights of Man, found their “higher law” in nature and natural law indeed, but in natural law reconceived in terms of the Marxian doctrine of the class conflict.[2]

To ask whether the natural rights philosophy of the Declaration of Independence is true or false is essentially a meaningless question. When honest men are impelled to withdraw their allegiance to the established law or custom of the community, still more when they are persuaded that such law or custom is too iniquitous to be longer tolerated, they seek for some principle more generally valid, some “law” of higher authority, than the established law or custom of the community. To this higher law or more generally valid principle they then appeal in justification of actions which the community condemns as immoral or criminal. They formulate the law or principle in such a way that it is, or seems to them to be, rationally defensible. To them it is “true” because it brings their actions into harmony with a rightly ordered universe and enables them to think of themselves as having chosen the nobler part, as having withdrawn from a corrupt world in order to serve God or Humanity or a force that makes for the highest good.

In different times this higher law has taken on different forms—the law of God revealed in Scripture, or in the inner light of conscience, or in nature; in nature conceived as subject to rational control, or in nature conceived as blind force subjecting men and things to its compulsion. The natural rights philosophy of the Declaration of Independence was one formulation of this idea of a higher law. It furnished at once a justification and a profound emotional inspiration for the revolutionary movements of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Founded upon a superficial knowledge of history it was, certainly; and upon a naïve faith in the instinctive virtues of humankind. Yet it was a humane and engaging faith. At its best it preached toleration in place of persecution, goodwill in place of hate, peace in place of war. It taught that beneath all local and temporary diversity, beneath the superficial traits and talents that distinguish men and nations, all men are equal in the possession of a common humanity; and to the end that concord might prevail on the earth instead of strife, it invited men to promote in themselves the humanity which bound them to their fellows, and to shape their conduct and their institutions in harmony with it.

This faith could not survive the harsh realities of the modern world. Throughout the nineteenth century the trend of action, and the trend of thought which follows and serves action, gave an appearance of unreality to the favorite ideas of the Age of Enlightenment. Nationalism and industrialism, easily passing over into an aggressive imperialism, a more trenchant scientific criticism steadily dissolving its own “universal and eternal laws” into a multiplicity of incomplete and temporary hypotheses—these provided an atmosphere in which faith in Humanity could only gasp for breath. “I have seen Frenchmen, Italians, Russians,” said Joseph de Maistre, “but as for Man, I declare I never met him in my life; if he exists, it is without my knowledge.”[3] Generally speaking, the nineteenth century doubted the existence of Man. Men it knew, and nations, but not Man. Man in General was not often inquired after. Friends of the Human Race were rarely to be found. Humanity was commonly abandoned to its own devices.

Introduction to the 1942 Reprint of The Declaration of Independence

My book on the Declaration of Independence, when it appeared in 1922, was well received, so far as I now recall, by all of the reviewers except one. This one, a passionate and easily irritated critic, and probably an irreclaimable prisoner of the Marxian philosophy, disapproved of the book altogether as a typical academic performance. He pointed out that the author, running true to form, was interested in documents to the exclusion of the living men whose activities give documents whatever significance they have. In the present instance this preoccupation with documents had enabled me, he thought, to treat a great subject with an ineptitude that amounted to a kind of sublime insolence: as evidence of which he referred to the chapter on the drafting of the Declaration—fifty-nine pages, which might have been devoted to saying something worth while about the men who bled and died for freedom, wasted in the futile enterprise of chasing down all the commas and semicolons employed in writing a document which was, at best, merely the formal statement of the freedom they died for. . . .

. . . The book is now republished from the original plates because Mr. Alfred Knopf, finding it out of print, was willing to take the risk involved in making it available to the public.[4] He may have thought that just now when political freedom, already lost in many countries, is everywhere threatened, the readers of books would be more than ordinarily interested in the political principles of the Declaration of Independence. Certainly recent events throughout the world have aroused an unwonted attention to the immemorial problem of human liberty. The incredible cynicism and brutality of Adolf Hitler’s ambitions, made every day more real by the servile and remorseless activities of his bleak-faced, humorless Nazi supporters, have forced men everywhere to reappraise the validity of half-forgotten ideas, and enabled them once more to entertain convictions as to the substance of things not evident to the senses. One of these convictions is that “liberty, equality, fraternity” and “the inalienable rights of men” are phrases, glittering or not, that denote realities—the fundamental realities that men will always fight for rather than surrender.[5]

It may then very well be that just now the reading public would welcome a book, the right kind of book, about the famous American charter of political freedom. Whether my book is the right kind of book is another matter. The general reader, I should think, is unlikely to be much edified by fifty-nine pages of textual criticism. He can of course skip it, and no harm done since it is mostly irrelevant to the main theme anyway. But will he find the rest of the book any more entertaining? Never having written a popular book, to say nothing of a bestseller, I am, unfortunately for me, obviously not well enough acquainted with the needs of the general reader to answer that question.

C.B.

Ithaca, New York

- 1. Becker refers here to Otto von Bismarck (1815–1989), a Prussian statesman, and to Italian political philosopher Niccoló Machiavelli (1469–1527), whose teachings are often said to counsel the ruthless pursuit and maintenance of political power.

- 2. Karl Marx (1818–1883) posited that the engine of historical progress is class struggle between the owners of capital (the bourgeoisie) and the workers (the proletariat).

- 3. In his original footnote, Becker cites Joseph de Maistre’s 1797 treatise, Considerations on France. Maistre (1753–1821) was a Savoyard philosopher writing after the turmoil of the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror.

- 4. Carl L. Becker, The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Ideas (New York: Vintage Books, 1942), v–xvii. Alfred A. Knopf (1892–1984) was an American publisher.

- 5. “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity,” a phrase with origins in the ideology of the French Revolution, is the official motto of France. Of course, the notion of the “inalienable rights of men” figured prominently in both the American and French Revolutions. U.S. senator Rufus Choate, a Massachusetts Whig, once suggested in the 1850s that the appeal of antislavery Whigs to the “glittering and sounding generalities” of the Declaration of Independence would tear apart the Union. In his April 6, 1859, letter to Henry L. Pierce, Abraham Lincoln took issue with Choate’s remark. Here, Lincoln labeled the “principles of Jefferson” “the definitions and axioms of a free society.”

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.