Introduction

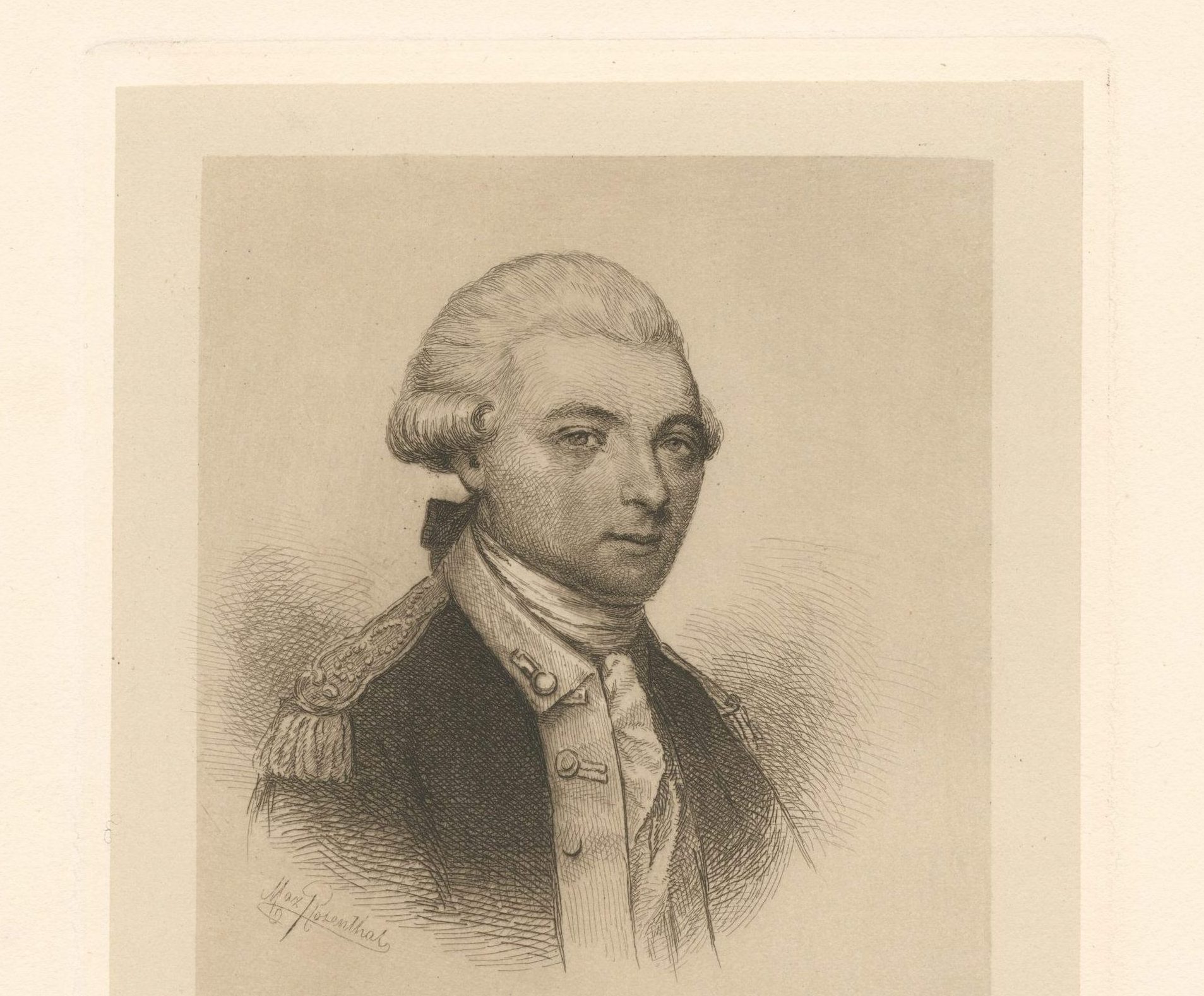

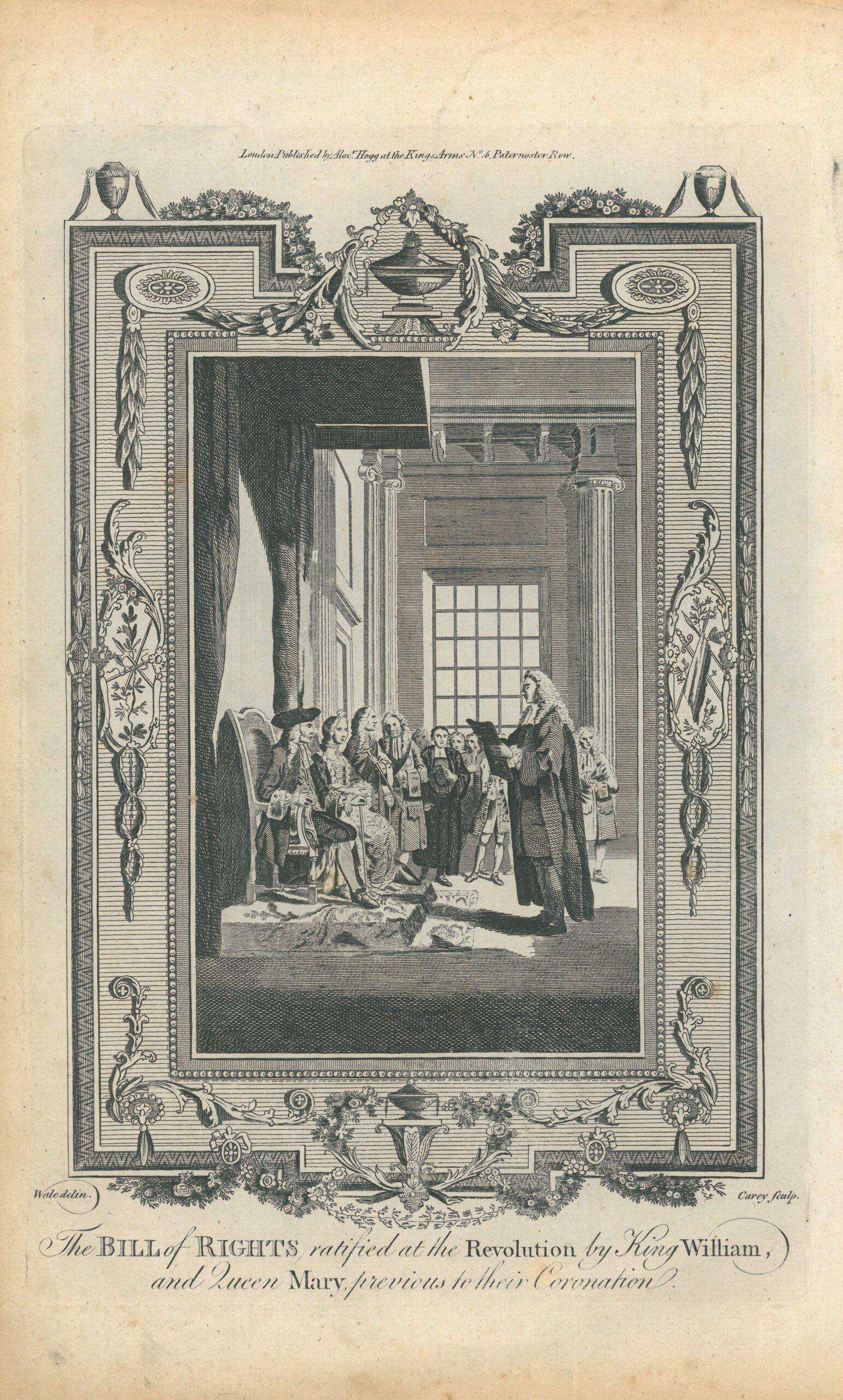

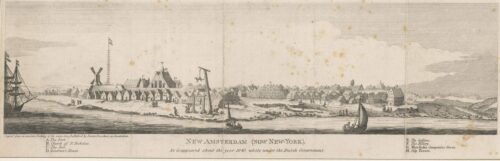

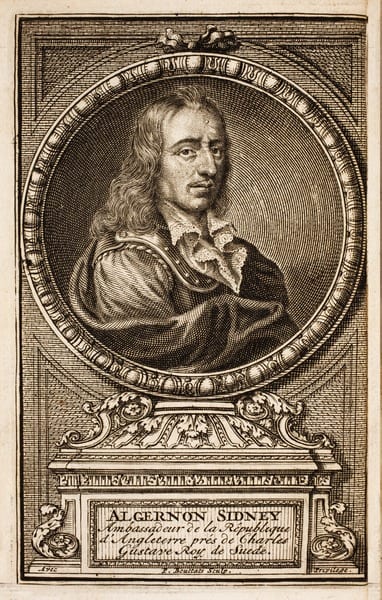

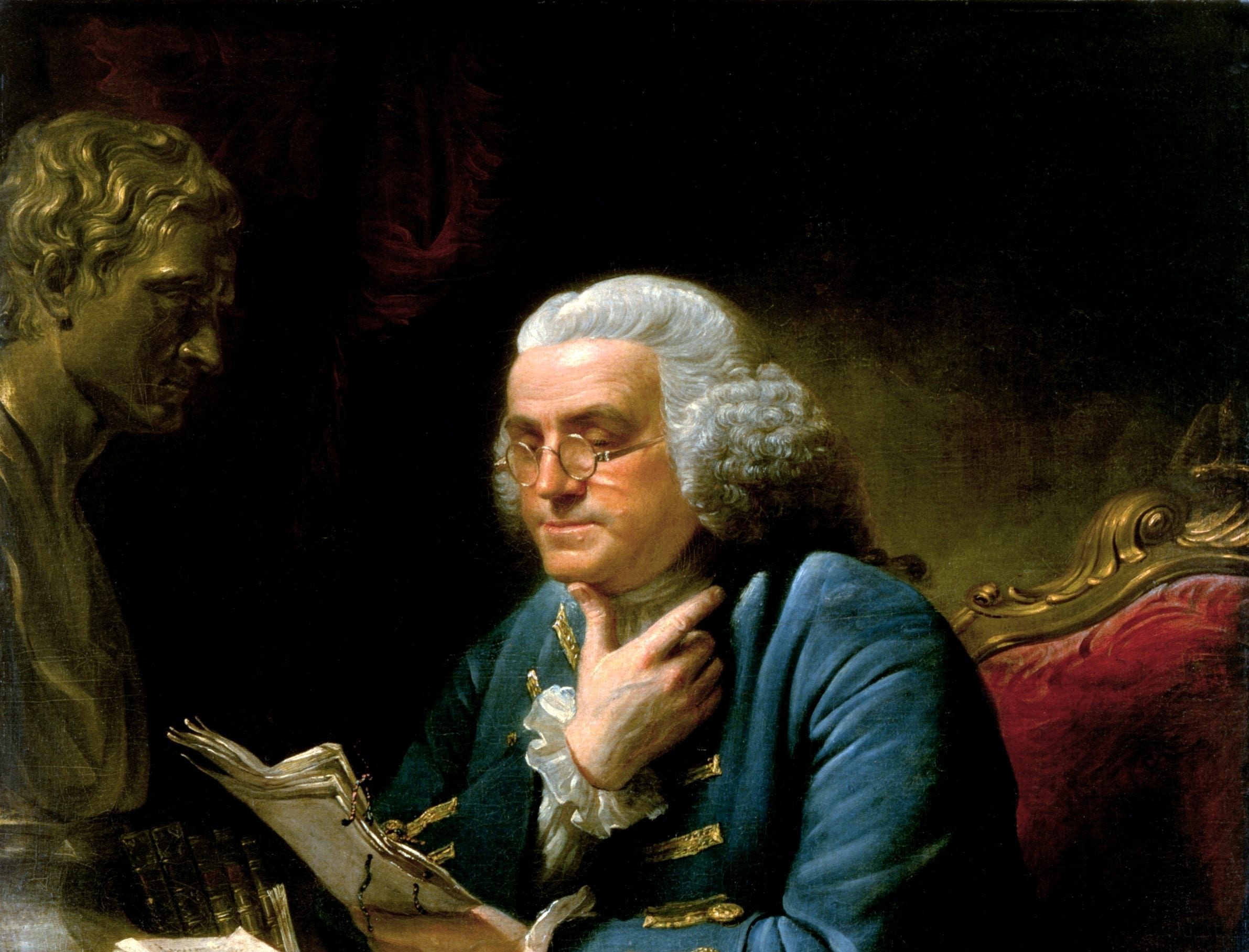

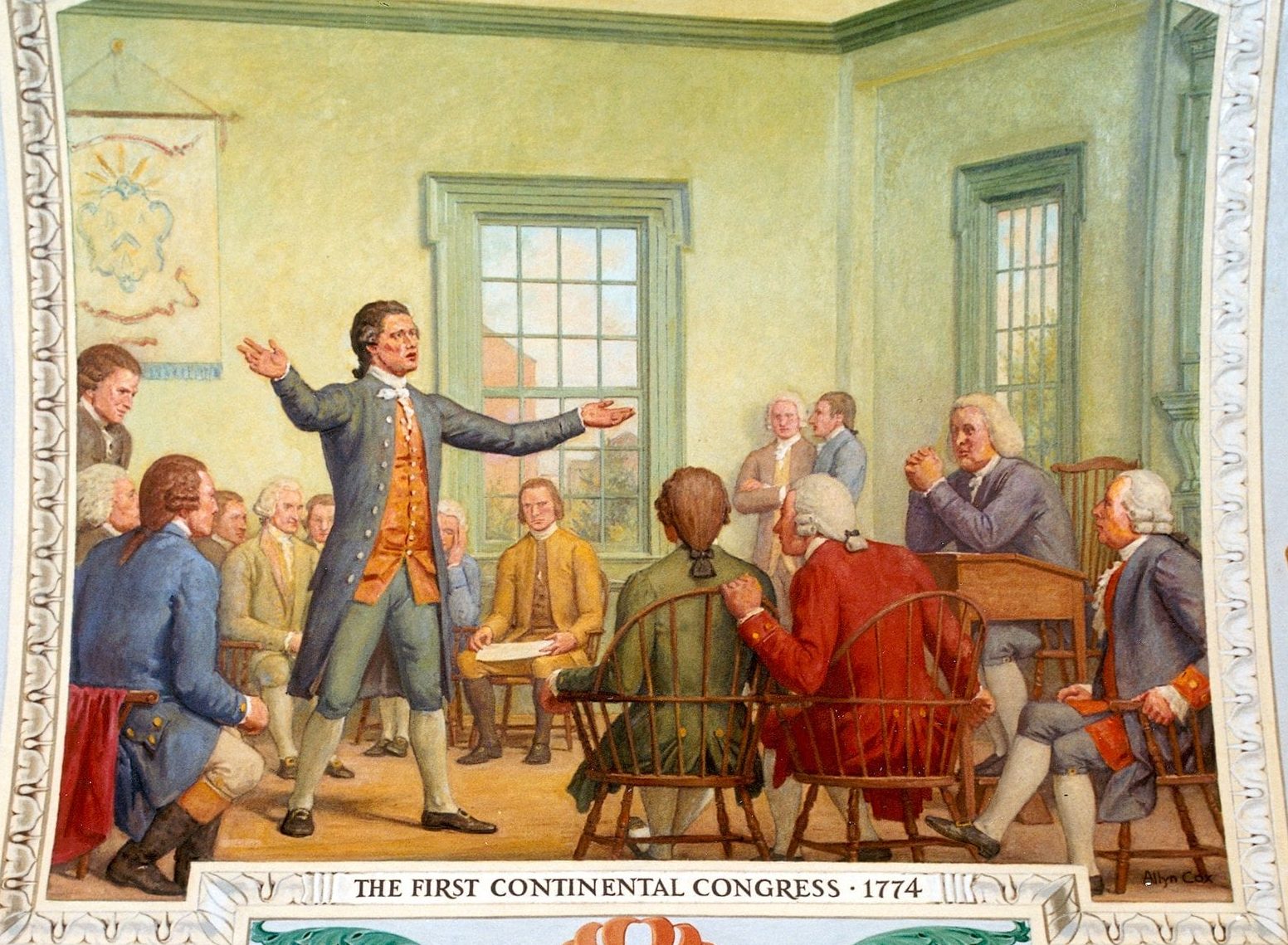

Of all the tragic figures of the American Revolution, few major officeholders experienced such a reversal of fortunes as Joseph Galloway (1731–1803). A lawyer who married into wealth, in 1756 Galloway became a member of the Pennsylvania General Assembly, which he led as speaker beginning in 1766. As a delegate to the First Continental Congress, Galloway proposed a constitutional solution to the imperial crisis through his Plan of Union, which would create “an inferior and distinct branch” of Parliament in the form of a “Grand Council” with representatives from each of the colonies. This legislature would elect its own speaker but serve under a “president general” appointed by the king. This intermediary layer of government between Parliament and the colonies would have the power to block measures of Parliament affecting the American colonies, which would retain their charters and control of their internal affairs.

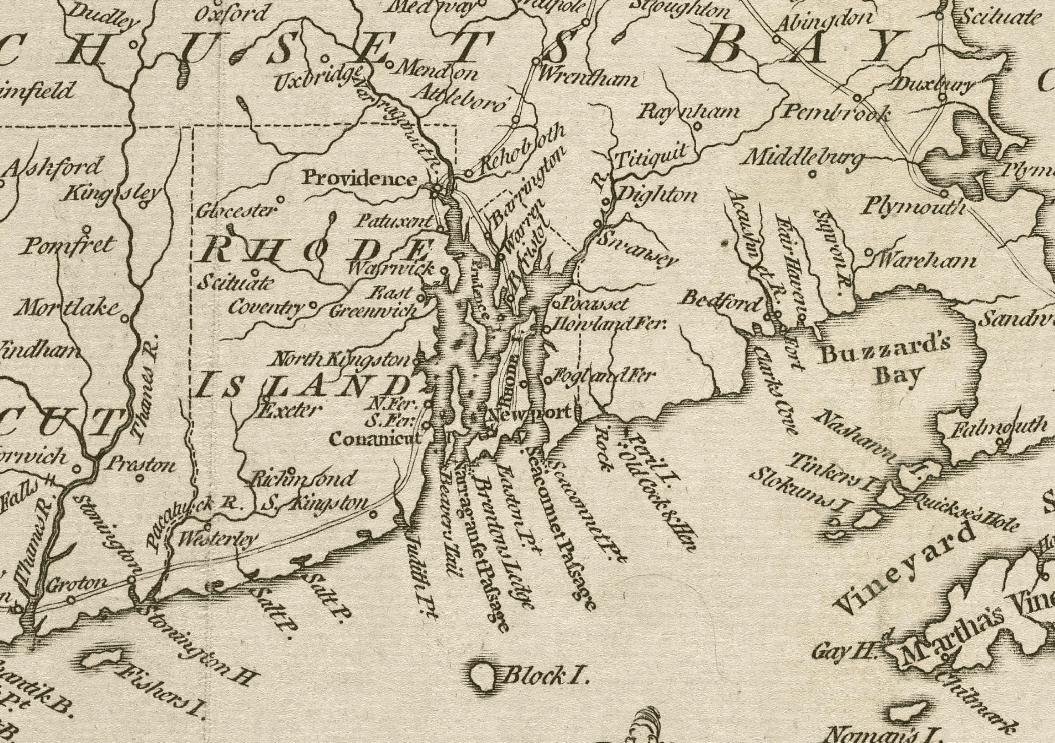

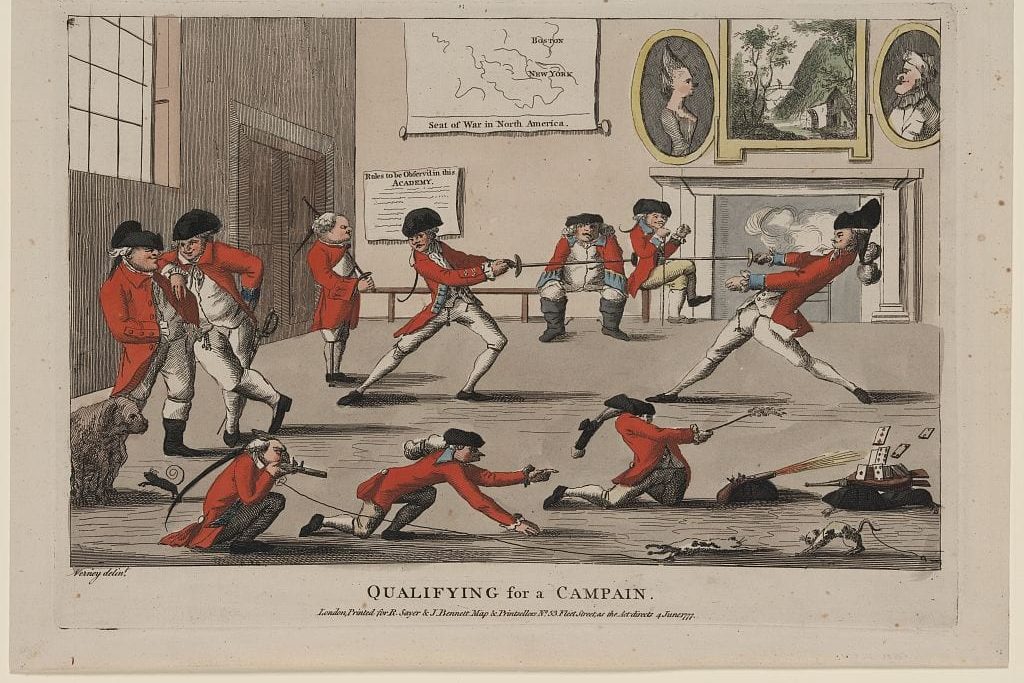

Whether Britain would have accepted Galloway’s Plan of Union is a matter for speculation. What is certain is that the First Continental Congress did not. Although his proposal appealed to many moderate delegates, after a day’s debate a motion was made to table the plan for consideration at some future date. The delegates seemed to recognize this as a polite way of killing Galloway’s idea. With the Rhode Island delegation divided, the states voted six to five in favor of the motion. This defeated not only Galloway’s plan but also his hopes for compromise. When the Second Continental Congress met the following year, he was not among its members. When it declared independence in 1776, Galloway, once a leader in the resistance movement, became a Loyalist. After aiding and abetting the British Army in its 1777–1778 capture and occupation of Philadelphia, he moved to Great Britain and never returned to his native land.

—Robert M.S. McDonald

Source: Worthington C. Ford, et al., eds., Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, 34 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904–37), 1:49–51. https://archive.org/details/journalsofcontin01unit/page/48

Resolved,That the Congress will apply to his majesty for a redress of grievances under which his faithful subjects in America labor; and assure him, that the colonies hold in abhorrence the idea of being considered independent communities on the British government, and most ardently desire the establishment of a political union, not only among themselves, but with the mother state, upon those principles of safety and freedom which are essential in the constitution of all free governments, and particularly that of the British legislature; and as the colonies from their local circumstances, cannot be represented in the Parliament of Great Britain, they will humbly propose to his majesty and his two houses of Parliament, the following plan, under which the strength of the whole empire may be drawn together on any emergency, the interest of both countries advanced, and the rights and liberties of America secured.

A plan of a proposed union between Great Britain and the colonies

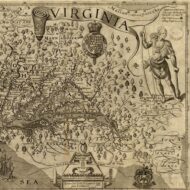

That a British and American legislature, for regulating the administration of the general affairs of America, be proposed and established in America, including all the said colonies; within, and under which government, each colony shall retain its present constitution, and powers of regulating and governing its own internal police, in all cases whatsoever.

That the said government be administered by a president general, to be appointed by the king, and a Grand Council, to be chosen by the representatives of the people of the several colonies, in their respective assemblies, once in every three years.

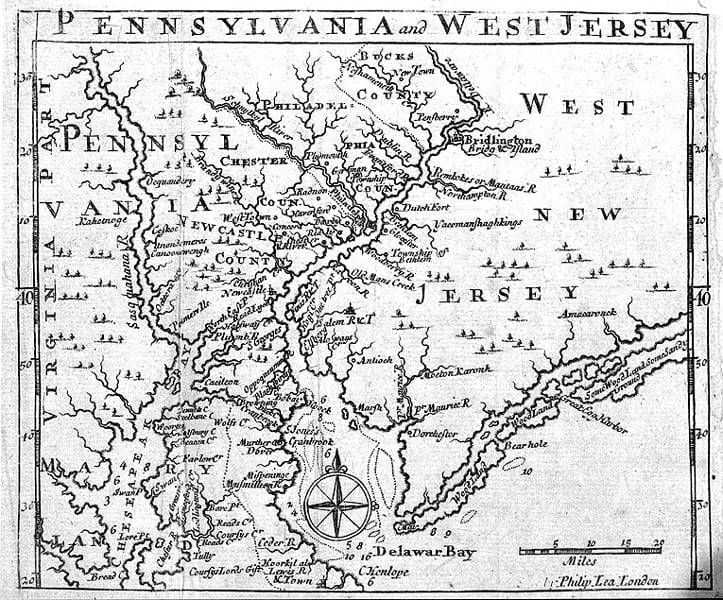

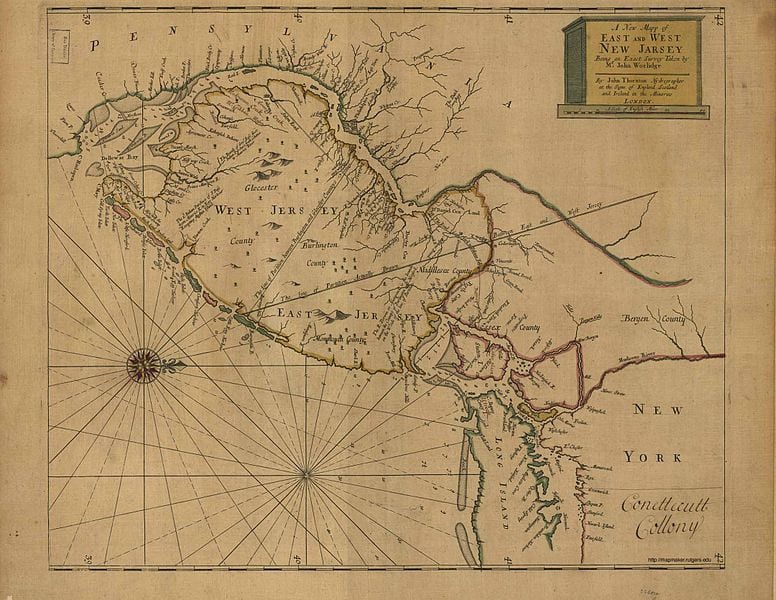

That the several assemblies shall choose members for the Grand Council in the following proportions:

New Hampshire.

Massachusetts Bay.

Rhode Island.

Connecticut.

New York.

New Jersey.

Pennsylvania.

Delaware Counties.

Maryland.

Virginia.

North Carolina.

South Carolina.

Georgia.

Who shall meet at the city of _______________ for the first time, being called by the president general, as soon as conveniently may be after his appointment.

That there shall be a new election of members for the Grand Council every three years; and on the death, removal, or resignation of any member, his place shall be supplied by a new choice, at the next sitting of assembly of the colony he represented.

That the Grand Council shall meet once in every year, if they shall think it necessary, and oftener, if occasions shall require, at such time and place as they shall adjourn to, at the last preceding meeting, or as they shall be called to meet at, by the president general, on any emergency.

That the Grand Council shall have power to choose their speaker, and shall hold and exercise all the like rights, liberties and privileges, as are held and exercised by and in the House of Commons of Great Britain.

That the president general shall hold his office during the pleasure of the king, and his assent shall be requisite to all acts of the Grand Council, and it shall be his office and duty to cause them to be carried into execution.

That the president general, by and with the advice and consent of the Grand Council, hold and exercise all the legislative rights, powers, and authorities, necessary for regulating and administering all the general police and affairs of the colonies, in which Great Britain and the colonies, or any of them, the colonies in general, or more than one colony, are in any manner concerned, as well civil and criminal as commercial.

That the said president general and the Grand Council, be an inferior and distinct branch of the British legislature, united and incorporated with it, for the aforesaid general purposes; and that any of the said general regulations may originate and be formed and digested, either in the Parliament of Great Britain, or in the said Grand Council, and being prepared, transmitted to the other for their approbation or dissent; and that the assent of both shall be requisite to the validity of all such general acts or statutes.

That in time of war, all bills for granting aid to the crown, prepared by the Grand Council, and approved by the president general, shall be valid and passed into a law, without the assent of the British Parliament.