Introduction

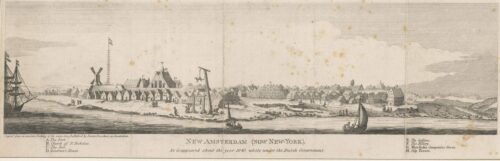

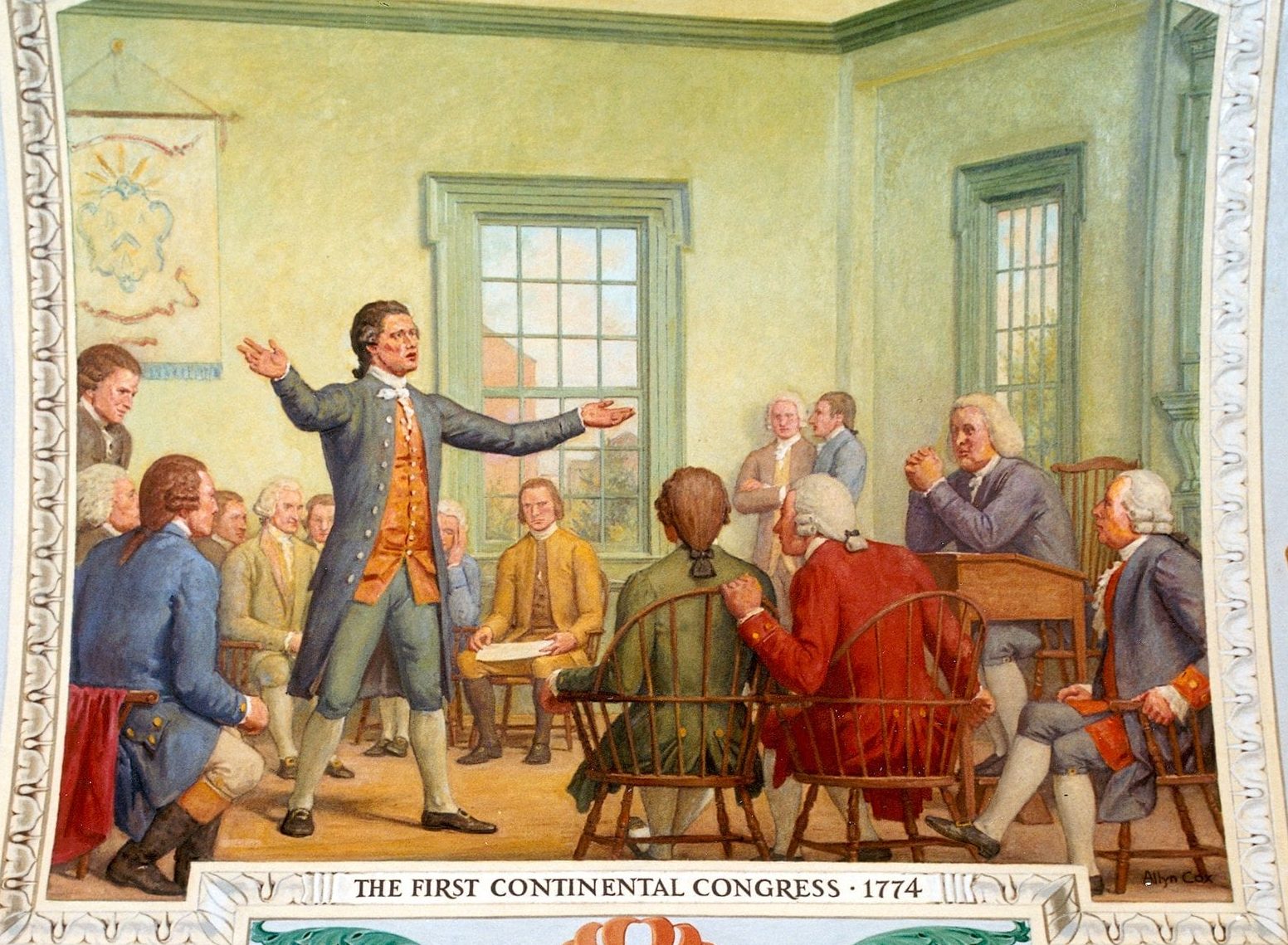

When news of the first measures that came to be known as the Coercive Acts reached New York City, the Sons of Liberty sprang to action, calling a large public meeting in Fraunces Tavern. Moderates within the city, fearing that this radical group would take things too far by imposing an embargo that would cripple the finances of local merchants, schemed to coopt the proceedings. Radicals learned of the moderates’ plan, however, forcing a compromise that resulted in the appointment of the “Committee of Fifty-one.” This body, which included members of both factions, would direct New York’s resistance efforts and call for a Continental Congress.

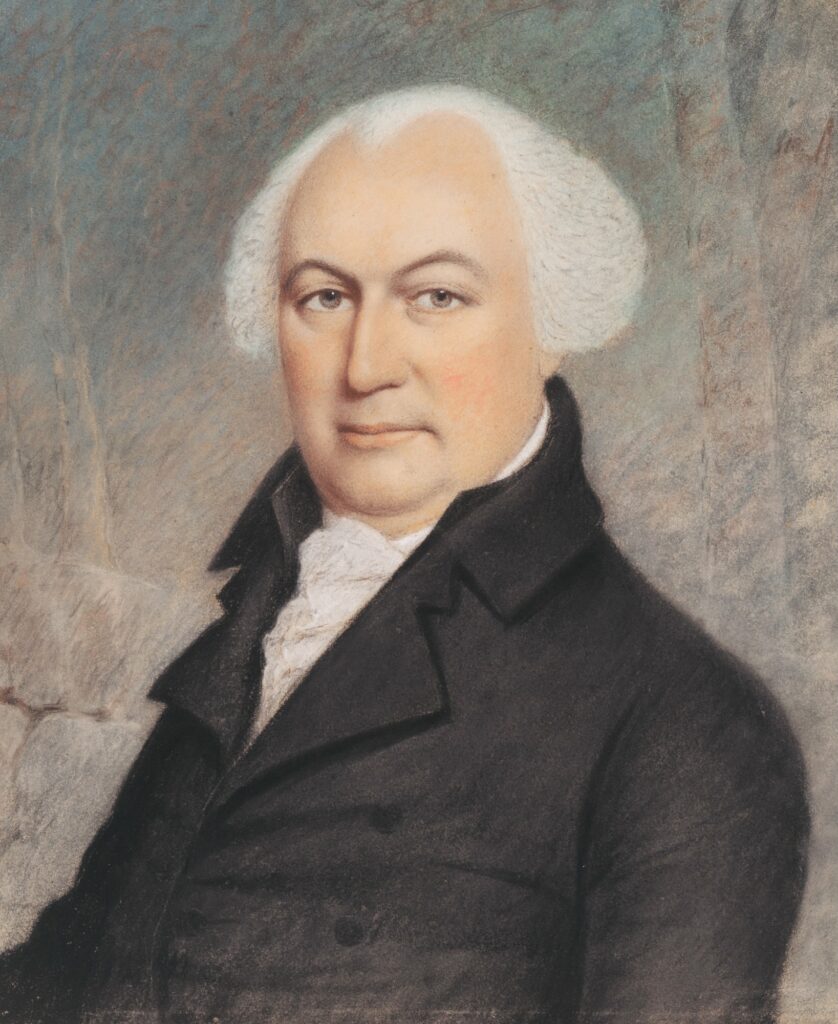

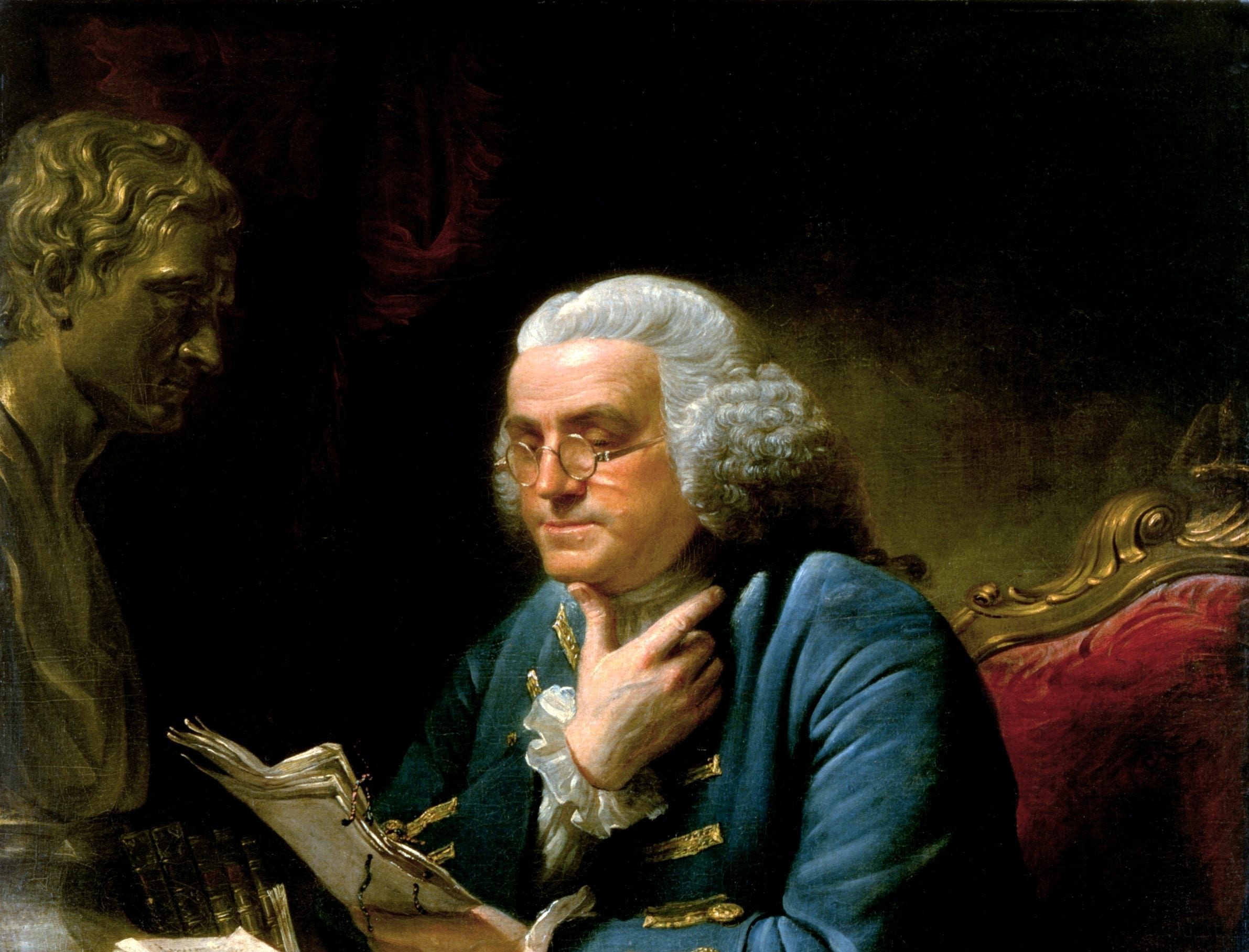

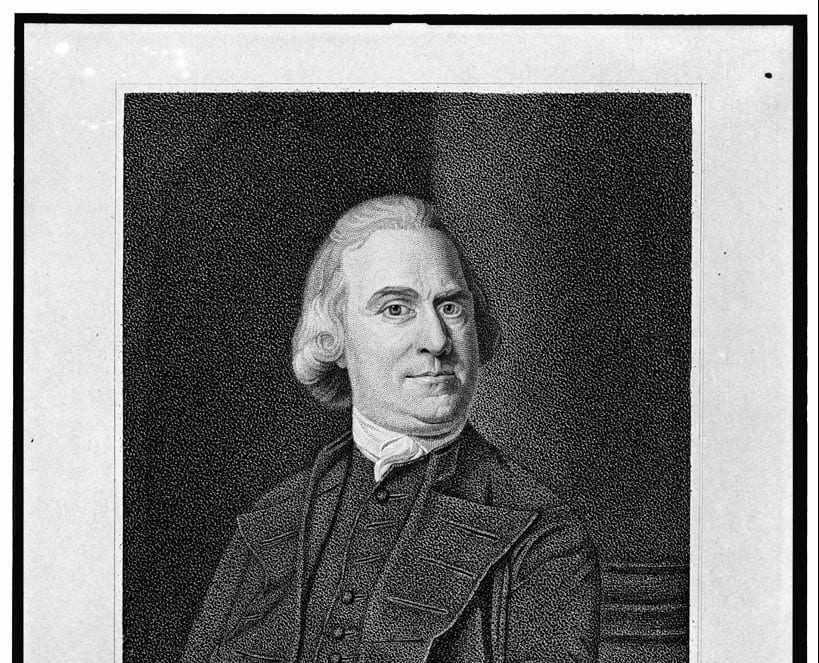

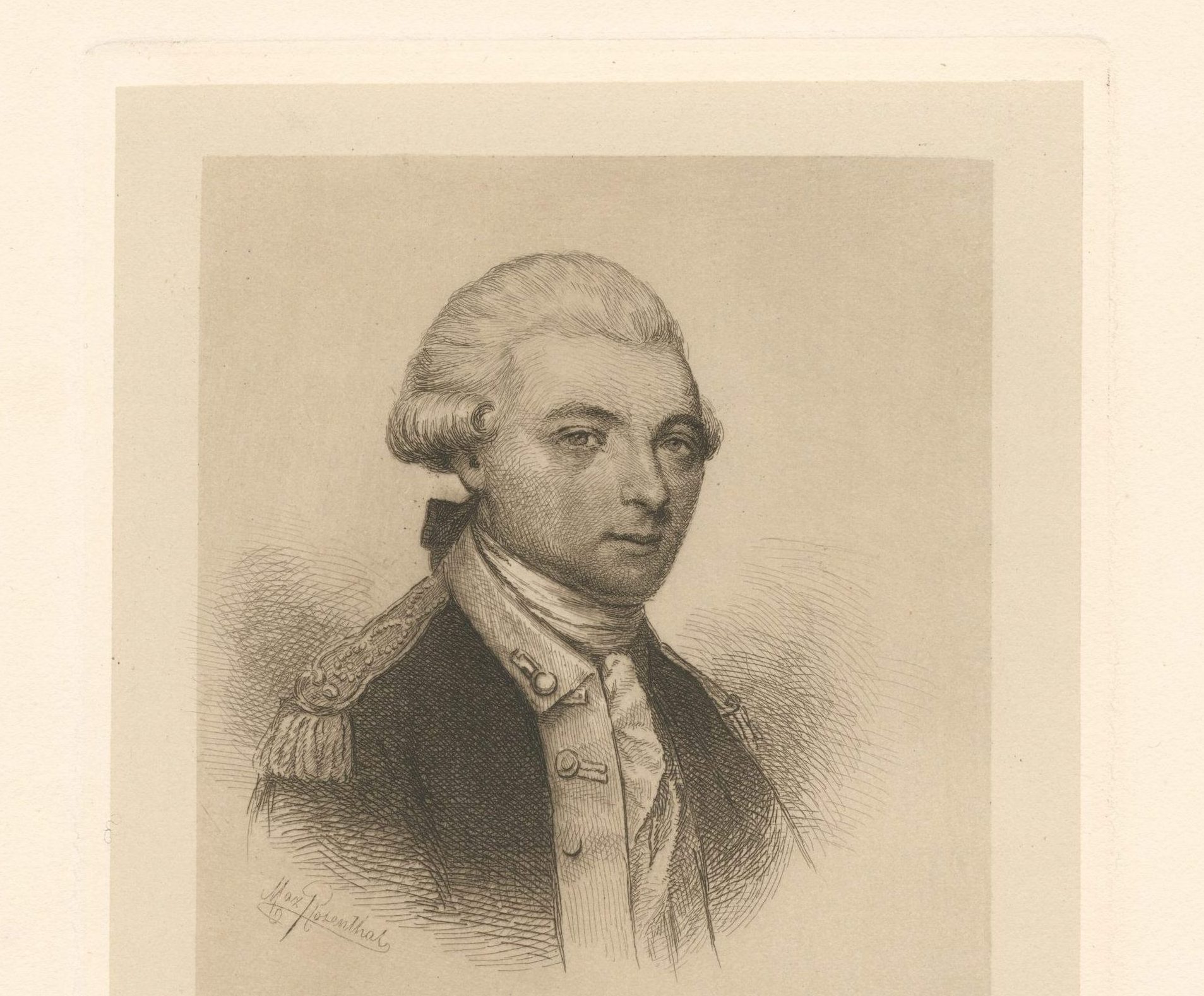

Since working people constituted the majority of the radicals and most of the moderates were men of some wealth, it was easy for Gouverneur Morris (1752–1816), a well-heeled New York attorney whose family owned a large portion of the Bronx, to view this episode as more than a minor dustup over the tactics of resistance. As Morris revealed in this letter to friend John Penn, he saw the controversy as evidence of rising tensions between the talented and educated “aristocracy” and the “shepherds” and “sheep” of the mob.

The fact that Morris and many other propertied men demonstrated a willingness to work with common people probably helps to explain why the American Revolution did not devolve into the sort of class conflict witnessed in the subsequent French Revolution. Morris would end up supporting independence, serving in the Continental Congress, signing the Articles of Confederation, and helping to draft the 1787 Constitution.

—Robert M.S. McDonald

Source: Peter Force, ed., American Archives: A Documentary History of the English Colonies, 4th ser., 6 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1837), 1:342–43.

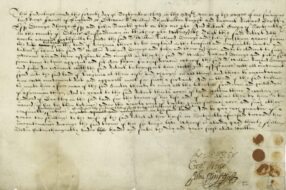

Gouverneur Morris to John Penn New York, May 20, 1774

You have heard, and you will hear, a great deal about politics, and in the heap of chaff you may find some grains of good sense. Believe me, sir, freedom and religion are only watchwords. We have appointed a committee, or rather we have nominated one. Let me give you the history of it. It is needless to premise, that the lower orders of mankind are more easily led by specious appearances than those of a more exalted station. This, and many similar propositions, you know better than your humble servant.

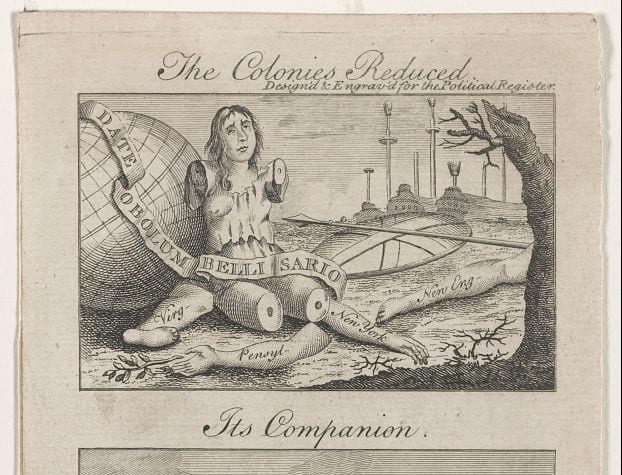

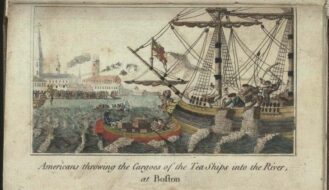

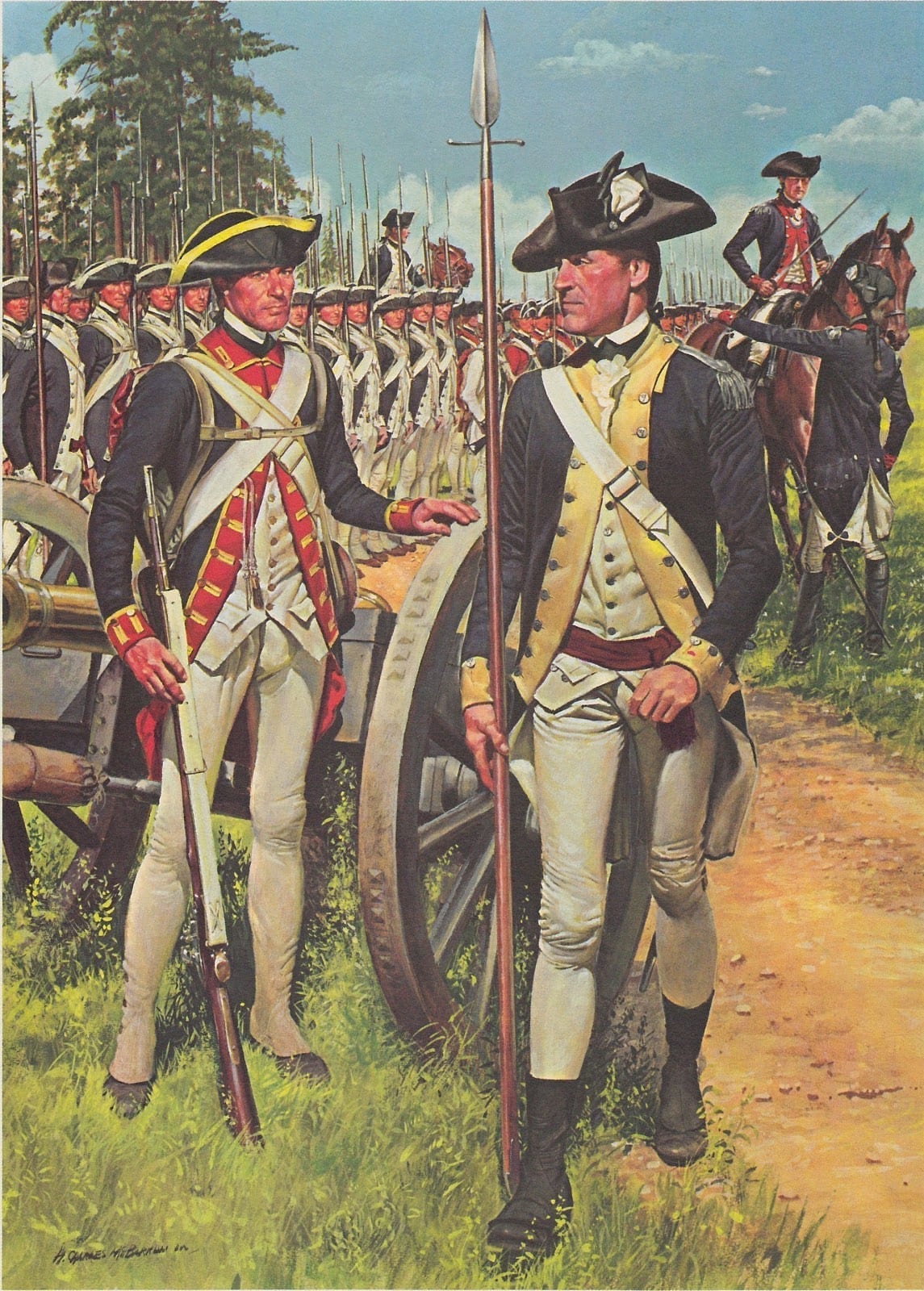

The troubles in America, during Grenville’s administration . . . stimulated some daring coxcombs to rouse the mob into an attack upon the bounds of order and decency. These fellows became . . . the leaders in all the riots, the bellwethers[2] of the flock….. On the whole, the shepherds were not much to blame in a politic point of view. The bellwethers jingled merrily, and roared out liberty, and property, and religion, and a multitude of cant terms, which everyone thought he understood, and was egregiously mistaken…. That we have been in hot water with the British Parliament ever since everybody knows…. The port of Boston has been shut up. These sheep, simple as they are, cannot be gulled as heretofore. In short, there is no ruling them; and now . . . the heads of the mobility[3] grow dangerous to the gentry, and how to keep them down is the question. While they correspond with the other colonies, call and dismiss popular assemblies, make resolves to bind the consciences of the rest of mankind, bully poor printers, and exert with full force all their other tribunitial[4] powers, it is impossible to curb them.

But art sometimes goes farther than force, and, therefore, to trick them handsomely a committee of patricians was to be nominated, and into their hands was to be committed the majesty of the people, and the highest trust was to be reposed in them…. The tribunes, through the want of good legerdemain[5] in the senatorial order, perceived the finesse; and yesterday I was present at a grand division of the city, and there I beheld my fellow citizens very accurately counting all their chickens, not only before any of them were hatched, but before above one half of the eggs were laid. In short, they fairly contended about the future forms of our government, whether it should be founded upon aristocratic or democratic principles.

I stood in the balcony, and on my right hand were ranged all the people of property, with some few poor dependents, and on the other all the tradesmen, etc., who thought it worth their while to leave daily labor for the good of the country. The spirit of the English Constitution has yet a little influence left, and but a little. The remains of it, however, will give the wealthy people a superiority this time, but would they secure it they must banish all schoolmasters and confine all knowledge to themselves. This cannot be. The mob begins to think and to reason. Poor reptiles! It is with them a vernal morning; they are struggling to cast off their winter’s slough, they bask in the sunshine, and before noon they will bite, depend upon it. The gentry begin to fear this. Their committee will be appointed, they will deceive the people, and again forfeit a share of their confidence. And if these instances of what with one side is policy, with the other perfidy, shall continue to increase, and become more frequent, farewell aristocracy. I see, and I see it with fear and trembling, that if the disputes with Great Britain continue, we shall be under the worst of all possible dominions; we shall be under the domination of a riotous mob.