No related resources

Introduction

In this landmark free speech case, decided 6–3, the Supreme Court ruled that the West Virginia Board of Education’s requirement for public school students to salute the flag violated the First Amendment. When West Virginia imposed the mandate, Jehovah’s Witnesses refused to comply and were subsequently sent home from school, threatened with expulsion, and potentially faced being placed in criminal reform schools for delinquent children.

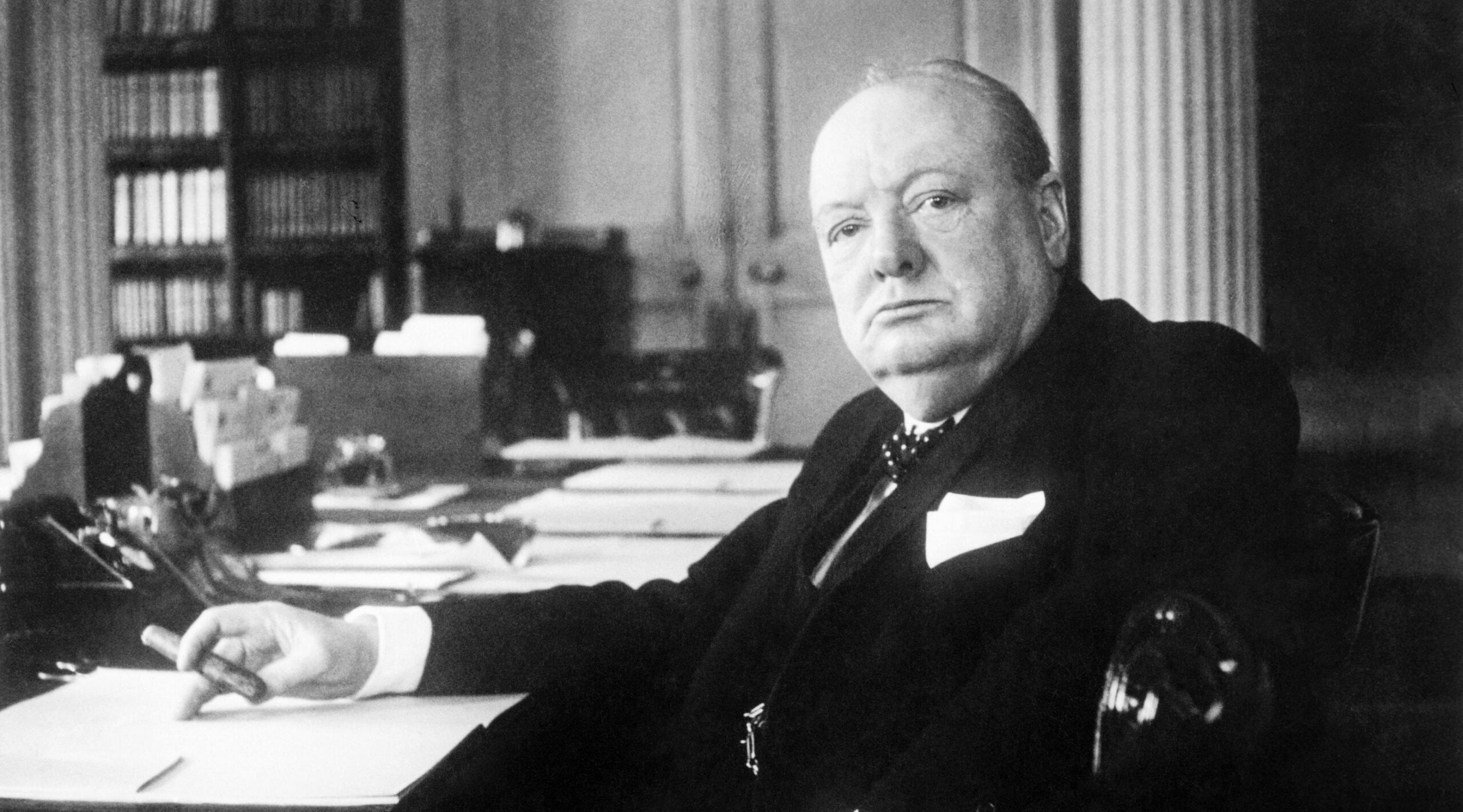

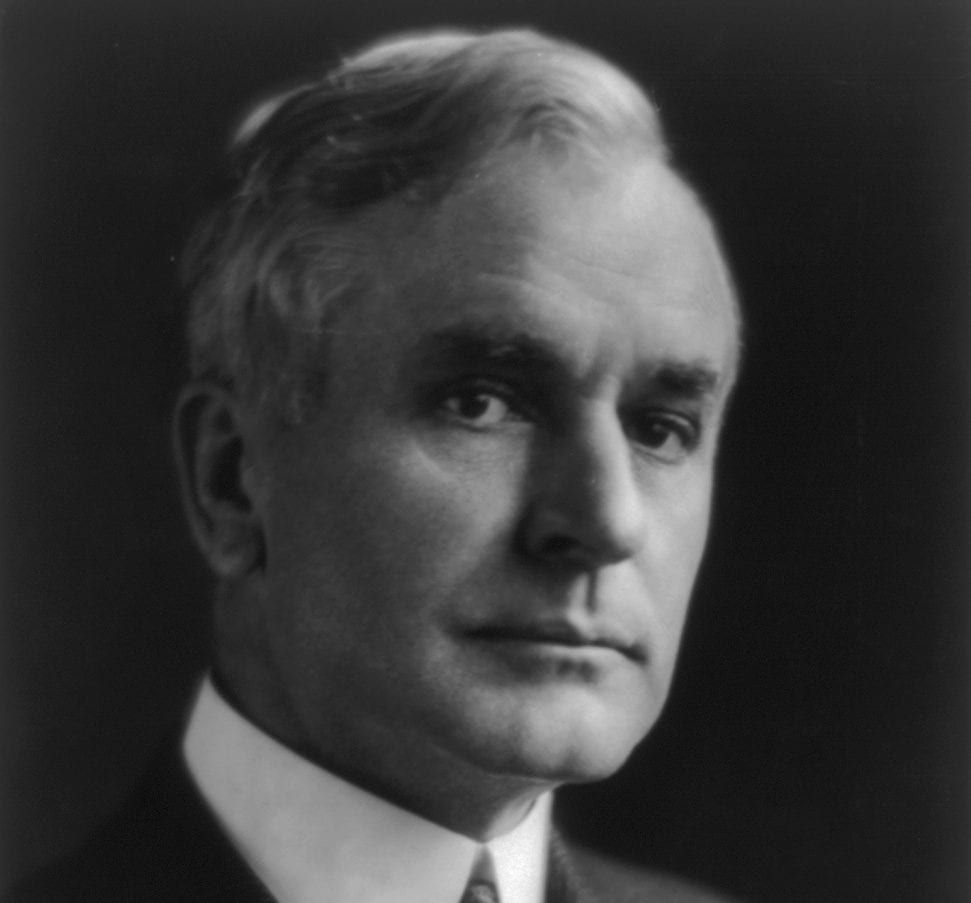

The majority decision for the Court, written by Justice Robert H. Jackson (1892–1954), famously declared that “if there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.” A salute, even though symbolic, was speech, and the government could not compel citizens to speak. The decision included a significant discussion of the Court’s proper role. Sensitive to the charge that the Court was setting itself up as a “school board” for the entire country, Jackson wrote, “The Fourteenth Amendment, as now applied to the states, protects the citizen against the state itself and all of its creatures—boards of education not excepted.” Jackson argued in effect that the Court’s duty to protect fundamental rights must take precedence over the authority of state legislatures to determine state policies.

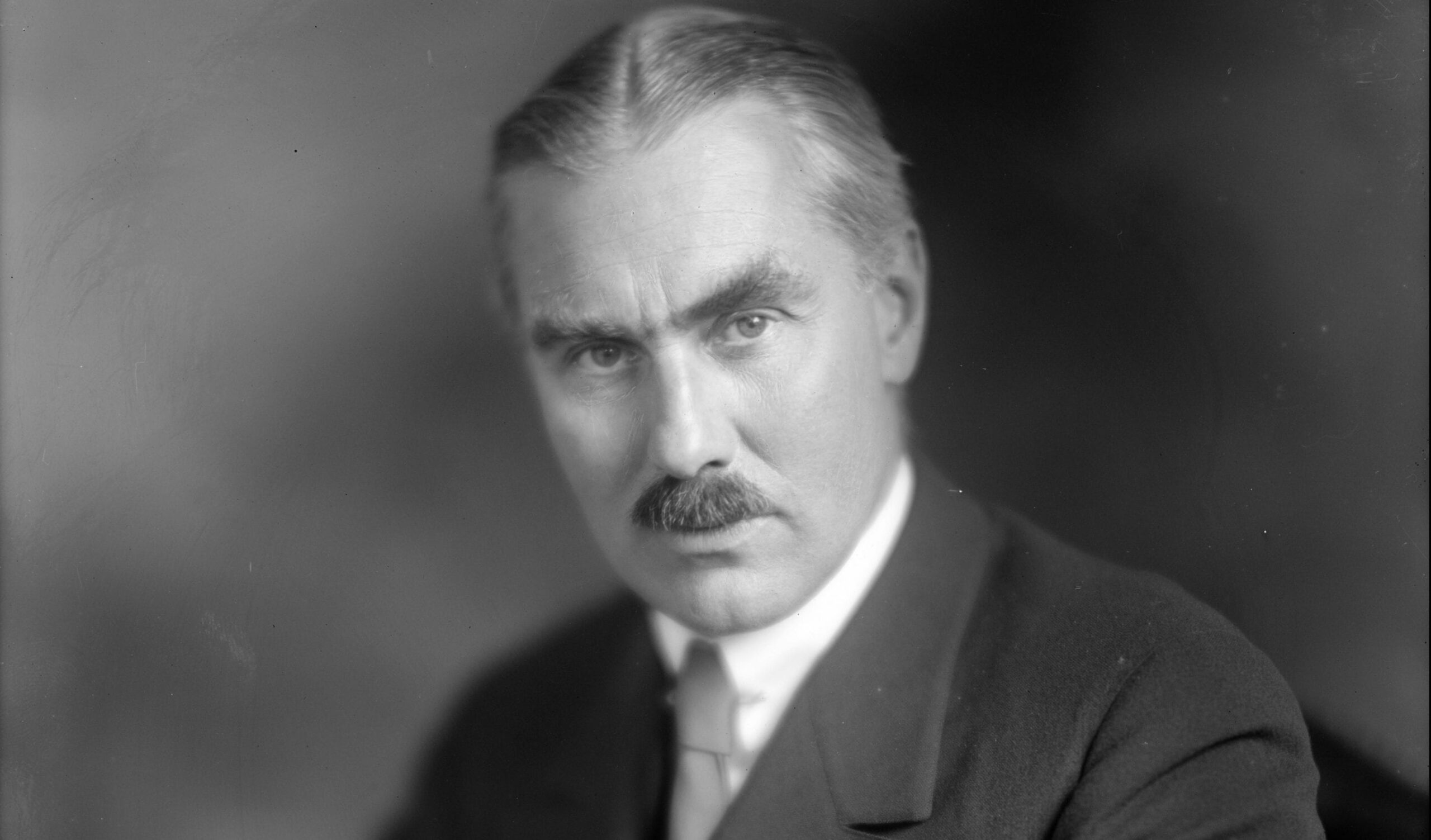

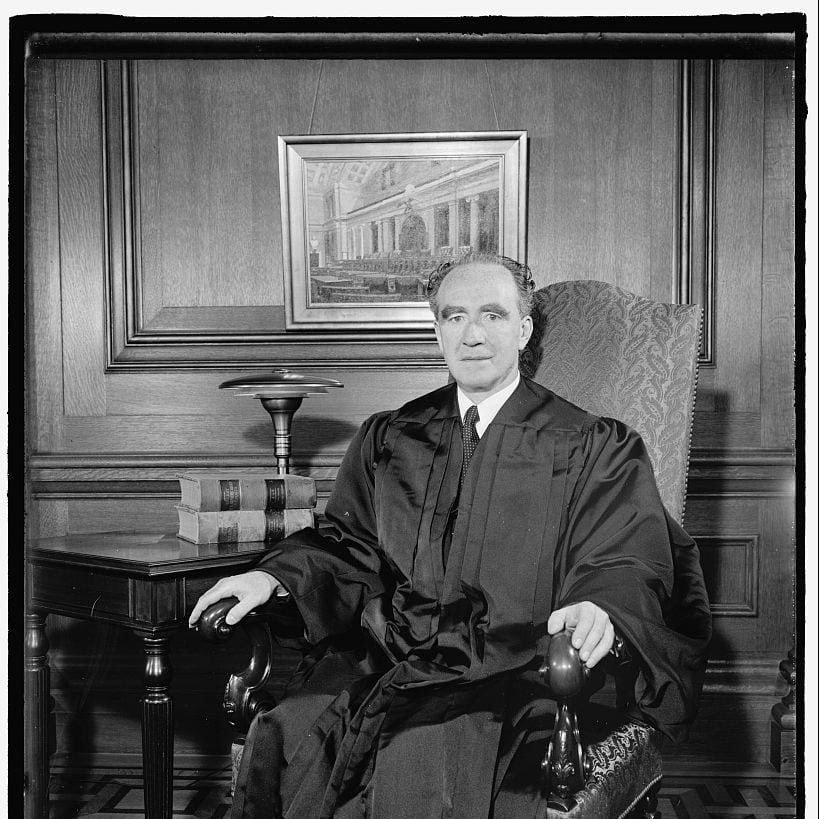

The person making the charge that the Court was exceeding its proper role in this case was Justice Felix Frankfurter (1882–1965). He defended West Virginia’s policy on constitutional grounds, writing that the requirement was not “the heedless action of some village tyrants”; West Virginia was a sovereign state entitled to respect under principles of federalism. The dissent is considered one of the classic statements of judicial restraint. Before being nominated to the Court by President Roosevelt, Frankfurter was a leading progressive legal scholar at Harvard Law School. The idea of judicial restraint was created and articulated by progressives in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in response to the Supreme Court’s Lochner era jurisprudence (See Lochner v. New York and Fireside Chat on the Reorganization of the Judiciary) and its skeptical attitude toward progressives’ economic regulations. Quoting Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes (1841–1935), Frankfurter argued that “it must be remembered that legislatures are ultimate guardians of the liberties and welfare of the people in quite as great a degree as the courts.” Frankfurter’s consistent concern throughout his career on the Court was that the increasing judicial resolution of conflicts would choke off political participation, which he regarded as the primary protector of civil rights.

Source: 319 U.S. 624, https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/319/624.

JUSTICE JACKSON delivered the opinion of the Court. . . .

. . . 2. It was also considered in the Gobitis1 case that functions of educational officers in states, counties, and school districts were such that to interfere with their authority “would in effect make us the school board for the country.” The Fourteenth Amendment, as now applied to the states, protects the citizen against the state itself and all of its creatures—boards of education not excepted. These have, of course, important, delicate, and highly discretionary functions, but none that they may not perform within the limits of the Bill of Rights. That they are educating the young for citizenship is reason for scrupulous protection of constitutional freedoms of the individual, if we are not to strangle the free mind at its source and teach youth to discount important principles of our government as mere platitudes.

3. The Gobitis opinion reasoned that this is a field “where courts possess no marked and certainly no controlling competence,” that it is committed to the legislatures as well as the courts to guard cherished liberties and that it is constitutionally appropriate to “fight out the wise use of legislative authority in the forum of public opinion and before legislative assemblies rather than to transfer such a contest to the judicial arena,” since all the “effective means of inducing political changes are left free.”

The very purpose of a Bill of Rights was to withdraw certain subjects from the vicissitudes of political controversy, to place them beyond the reach of majorities and officials and to establish them as legal principles to be applied by the courts. One’s right to life, liberty, and property, to free speech, a free press, freedom of worship and assembly, and other fundamental rights may not be submitted to vote; they depend on the outcome of no elections.

The freedoms of speech and of press, of assembly, and of worship may not be infringed on slender grounds. They are susceptible of restriction only to prevent grave and immediate danger to interests which the state may lawfully protect. . . . Nor does our duty to apply the Bill of Rights to assertions of official authority depend upon our possession of marked competence in the field where the invasion of rights occurs. . . .

JUSTICE FRANKFURTER, dissenting:

One who belongs to the most vilified and persecuted minority in history is not likely to be insensible to the freedoms guaranteed by our Constitution. Were my purely personal attitude relevant, I should wholeheartedly associate myself with the general libertarian views in the Court’s opinion, representing, as they do, the thought and action of a lifetime. But, as judges, we are neither Jew nor Gentile, neither Catholic nor agnostic. We owe equal attachment to the Constitution, and are equally bound by our judicial obligations whether we derive our citizenship from the earliest or the latest immigrants to these shores. . . .It can never be emphasized too much that one’s own opinion about the wisdom or evil of a law should be excluded altogether when one is doing one’s duty on the bench. The only opinion of our own even looking in that direction that is material is our opinion whether legislators could, in reason, have enacted such a law. In the light of all the circumstances, including the history of this question in this Court, it would require more daring than I possess to deny that reasonable legislators could have taken the action which is before us for review. Most unwillingly, therefore, I must differ from my brethren with regard to legislation like this. I cannot bring my mind to believe that the “liberty” secured by the due process clause gives this Court authority to deny to the state of West Virginia the attainment of that which we all recognize as a legitimate legislative end, namely, the promotion of good citizenship, by employment of the means here chosen. . . .

The admonition that judicial self-restraint alone limits arbitrary exercise of our authority is relevant every time we are asked to nullify legislation. The Constitution does not give us greater veto power when dealing with one phase of “liberty” than with another, or when dealing with grade school regulations than with college regulations that offend conscience. In neither situation is our function comparable to that of a legislature, nor are we free to act as though we were a super-legislature. Judicial self-restraint is equally necessary whenever an exercise of political or legislative power is challenged. There is no warrant in the constitutional basis of this Court’s authority for attributing different roles to it depending upon the nature of the challenge to the legislation. Our power does not vary according to the particular provision of the Bill of Rights which is invoked. The right not to have property taken without just compensation has, so far as the scope of judicial power is concerned, the same constitutional dignity as the right to be protected against unreasonable searches and seizures, and the latter has no less claim than freedom of the press or freedom of speech or religious freedom. In no instance is this Court the primary protector of the particular liberty that is invoked. . . .

When Mr. Justice Holmes, speaking for this Court, wrote that “it must be remembered that legislatures are ultimate guardians of the liberties and welfare of the people in quite as great a degree as the courts,”2 he went to the very essence of our constitutional system and the democratic conception of our society. He did not mean that for only some phases of civil government this Court was not to supplant legislatures and sit in judgment upon the right or wrong of a challenged measure. He was stating the comprehensive judicial duty and role of this Court in our constitutional scheme whenever legislation is sought to be nullified on any ground, namely, that responsibility for legislation lies with legislatures, answerable as they are directly to the people, and this Court’s only and very narrow function is to determine whether, within the broad grant of authority vested in legislatures, they have exercised a judgment for which reasonable justification can be offered. . . .

. . .[T]he framers of the Constitution denied . . . legislative powers to the federal judiciary. They chose instead to insulate the judiciary from the legislative function. They did not grant to this Court supervision over legislation. . . .

We are not reviewing merely the action of a local school board. The flag salute requirement in this case comes before us with the full authority of the state of West Virginia. We are, in fact, passing judgment on “the power of the state as a whole.” Practically, we are passing upon the political power of each of the forty-eight states. Moreover, since the First Amendment has been read into the Fourteenth, our problem is precisely the same as it would be if we had before us an act of Congress for the District of Columbia. To suggest that we are here concerned with the heedless action of some village tyrants is to distort the augustness of the constitutional issue and the reach of the consequences of our decision. . . .

. . . But the real question is, who is to make such accommodations, the courts or the legislature?

This is no dry, technical matter. It cuts deep into one’s conception of the democratic process—it concerns no less the practical differences between the means for making these accommodations that are open to courts and to legislatures. A court can only strike down. It can only say “This or that law is void.” It cannot modify or qualify, it cannot make exceptions to a general requirement. And it strikes down not merely for a day. At least the finding of unconstitutionality ought not to have ephemeral significance unless the Constitution is to be reduced to the fugitive importance of mere legislation. When we are dealing with the Constitution of the United States, and, more particularly, with the great safeguards of the Bill of Rights, we are dealing with principles of liberty and justice “so rooted in the traditions and conscience of our people as to be ranked as fundamental”—something without which “a fair and enlightened system of justice would be impossible.” If the function of this Court is to be essentially no different from that of a legislature, if the considerations governing constitutional construction are to be substantially those that underlie legislation, then indeed judges should not have life tenure, and they should be made directly responsible to the electorate. . . .

Of course, patriotism cannot be enforced by the flag salute. But neither can the liberal spirit be enforced by judicial invalidation of illiberal legislation. Our constant preoccupation with the constitutionality of legislation, rather than with its wisdom, tends to preoccupation of the American mind with a false value. The tendency of focusing attention on constitutionality is to make constitutionality synonymous with wisdom, to regard a law as all right if it is constitutional. Such an attitude is a great enemy of liberalism. Particularly in legislation affecting freedom of thought and freedom of speech, much which should offend a free-spirited society is constitutional. Reliance for the most precious interests of civilization, therefore, must be found outside of their vindication in courts of law. Only a persistent positive translation of the faith of a free society into the convictions and habits and action of a community is the ultimate reliance against unabated temptations to fetter the human spirit. . . .

- 1. Minersville School District v. Gobitis, 310 U.S. 586 (1940). In this case, the Supreme Court ruled that a school district could compel Jehovah’s Witnesses to recite the Pledge of Allegiance and salute the flag. West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette overturned Gobitis.

- 2. Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railway Company v. May, 194 U.S. 270 (1904).

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.