Introduction

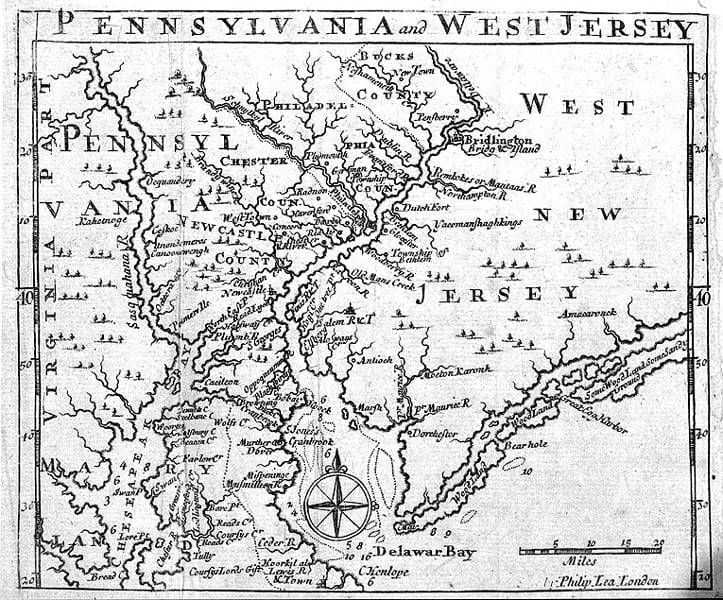

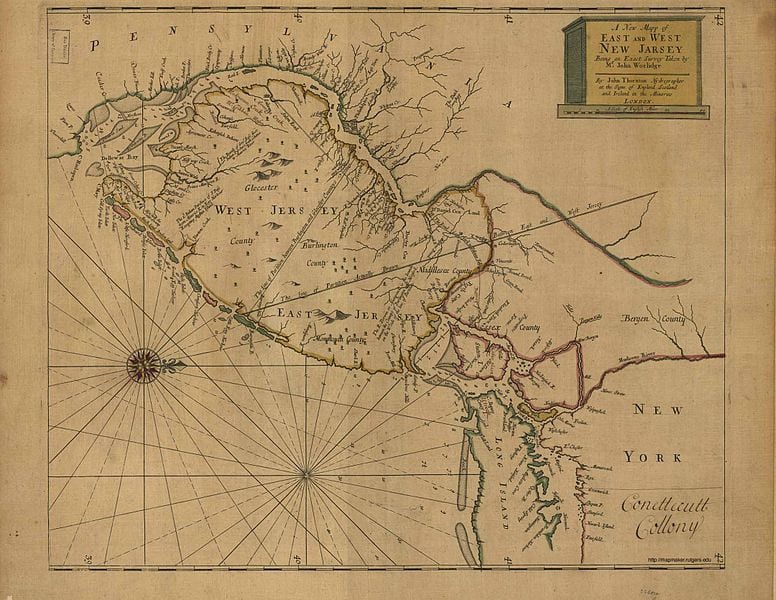

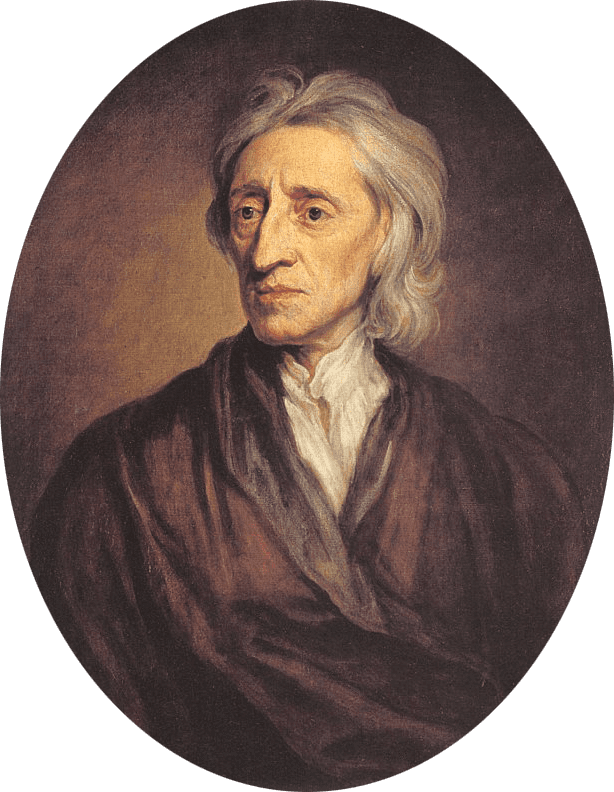

When they settled in North America, the colonists brought their religious beliefs with them. In most instances, this was accomplished not only as a matter of social or cultural transmission, but by acts of legislative authority that provided public funding for certain religious denominations and not for others. Only Pennsylvania, Delaware, Rhode Island and (possibly) New Jersey failed to establish a particular denomination at some point during the colonial period: in the other colonies, religious establishments were the norm, and generally seen as for the institutional benefit of both church and state, as well as in accordance with the public good. Some colonies (such as Maryland and New York) combined religious establishments with limited toleration for religious dissenters. Yet even in Pennsylvania (Documents A and B), although the law was ostensibly “tolerant” of religious variety and protective of freedom of conscience in principle, there remained an underlying presumption that individual religious faith in a broadly Protestant sense (sometimes extended to include Catholics and, more rarely, Jews) was a necessary component of civil order.

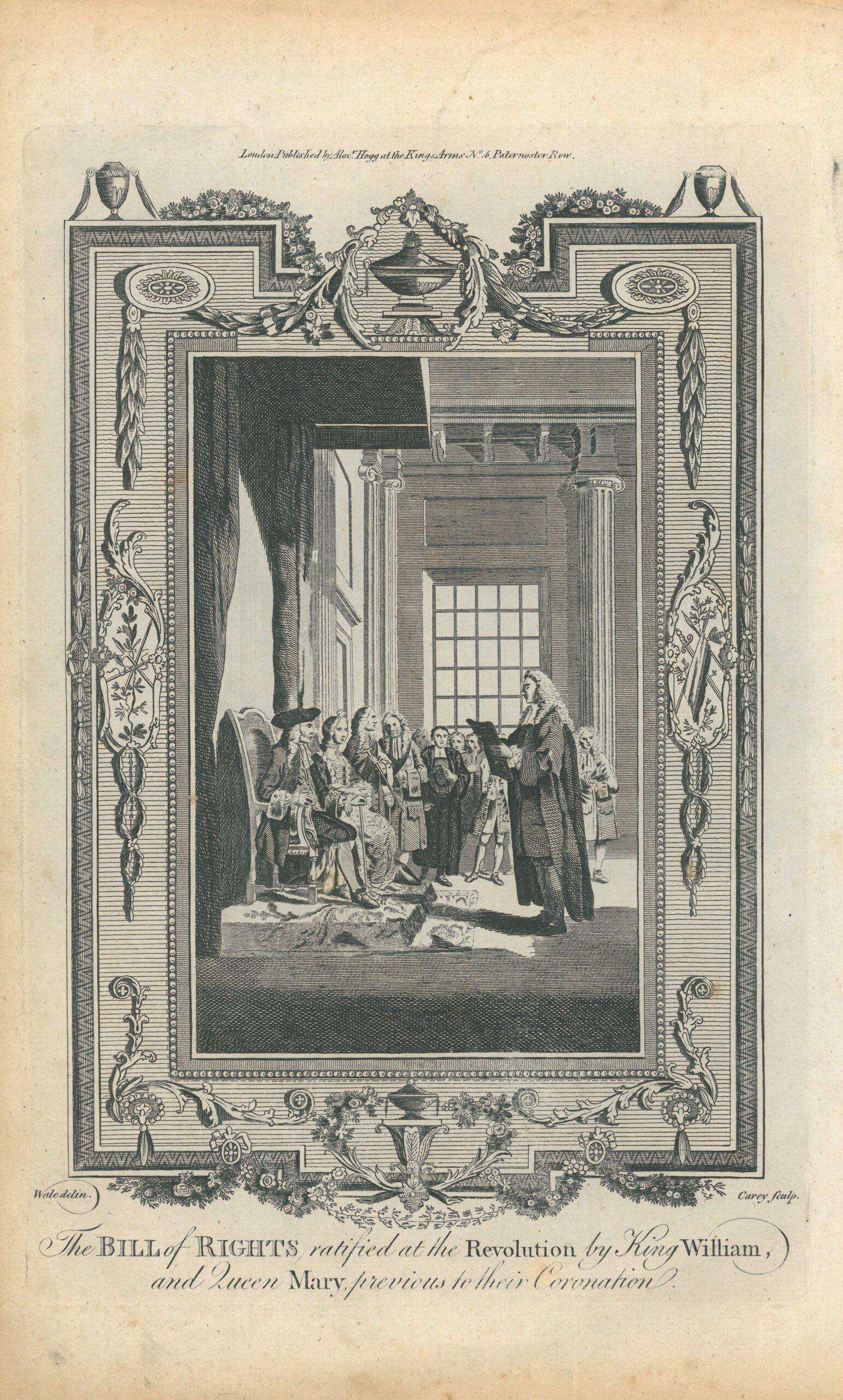

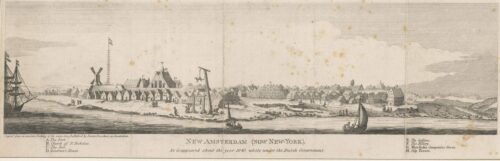

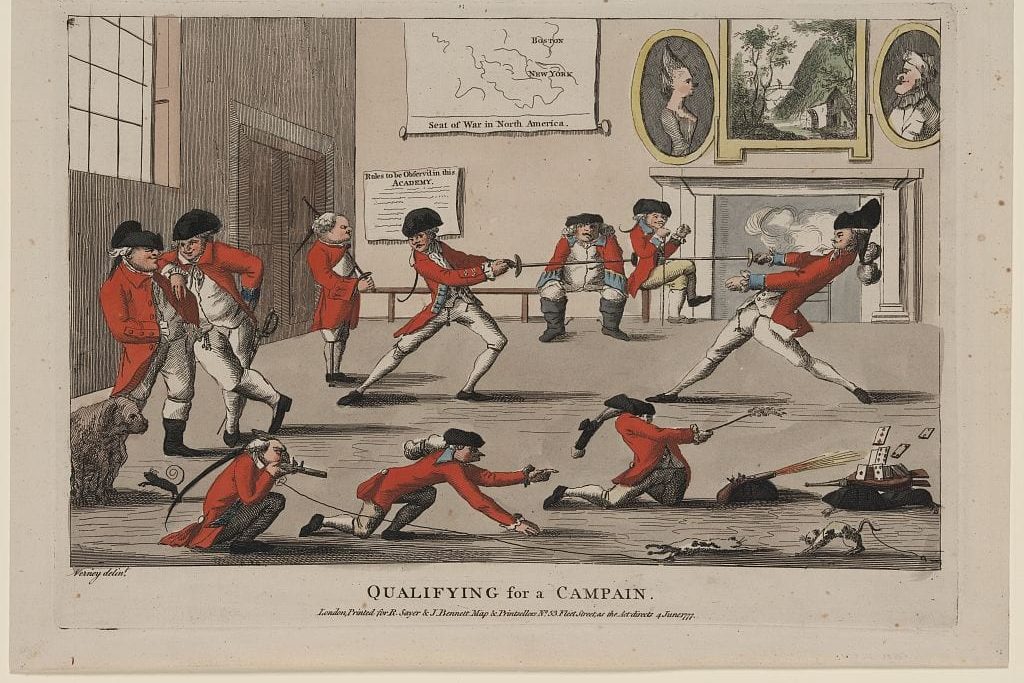

The difficulty of maintaining this latter assumption while at the same time holding to an expansive understanding of freedom of conscience became even more apparent when, following the Glorious Revolution, William and Mary signed the Toleration Act of 1689 granting freedom of worship to all Protestants regardless of sect throughout the British Empire. England and her Atlantic colonies soon became a haven for religious refugees from less-tolerant European regimes. After their arrival in places like New York, which already had large and religiously diverse non-English populations, the colonies began to seem “very much divided,” at least in the eyes of those used to greater religious conformity (Documents C and F). Indeed, the vibrant but worrisome diversity of religion in the colonies was the impetus behind efforts to establish the Church of England more strongly as a means of asserting royal authority and creating greater political as well as cultural unity. (See Chapter 5.)

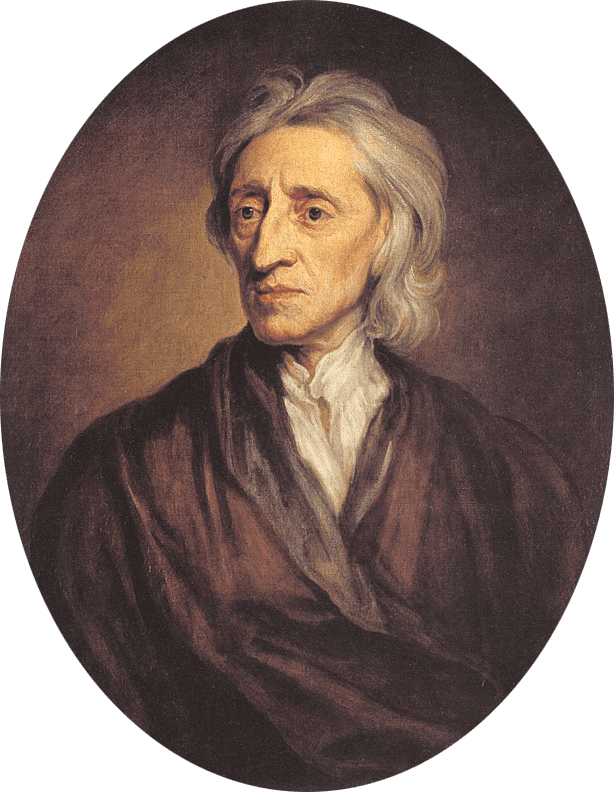

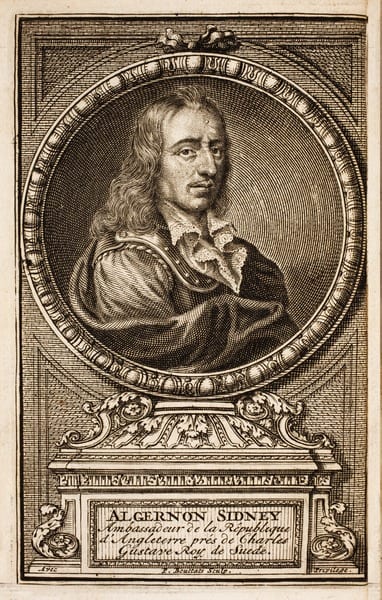

As scholar and statesman Elisha Williams’ tract, The Essential Rights and Liberties of Protestants (Document E) makes clear, however, for many colonists, religious freedom was seen as a natural and inalienable right, one that they would increasingly associate with other political rights worth fighting for—with words when possible, and weapons when necessary—as the century wore on.

Documents in this chapter are available separately by following the hyperlinks below:

- William Penn, Pennsylvania: Frame of Government, 1682

- Pennsylvania: An Act for Freedom of Conscience, 1682

- John Miller, “As to their religion, they are very much divided,”1695

- Benjamin Franklin, George Whitefield Preaches in Philadelphia, 1739

- Elisha Williams, The Essential Rights and Liberties of Protestants, 1744

- Gottlieb Mittelberger, “Liberty in Pennsylvania is more hurtful than useful,” 1750

William Penn, Pennsylvania: Frame of Government, 16821

THE PREFACE

. . . This the Apostle2 teaches in diverse of his epistles: “The law (says he) was added because of transgression.” In another place, “Knowing that the law was not made for the righteous man, but for the disobedient and ungodly, for sinners, for unholy and profane, for murderers, for whoremongers, for them that defile themselves with mankind, and for man-stealers, for liars, for perjured persons,”3 &c.; but this is not all, he opens and carries the matter of government a little further: “Let every soul be subject to the higher powers; for there is no power but of God. The powers that be are ordained of God: whosoever therefore resisteth the power, resisteth the ordinance of God. For rulers are not a terror to good works, but to evil: wilt thou then not be afraid of the power? Do that which is good, and thou shalt have praise of the same.” “He is the minister of God to thee for good.” “Wherefore ye must needs be subject, not only for wrath, but for conscience’ sake.”4

This settles the divine right of government beyond exception, and that for two ends: first, to terrify evil doers: secondly, to cherish those that do well; which gives government a life beyond corruption, and makes it as durable in the world, as good men shall be. So that government seems to me a part of religion itself, a thing sacred in its institution and end. For, if it does not directly remove the cause, it crushes the effects of evil, and is as such, (though a lower, yet) an emanation of the same Divine Power, that is both author and object of pure religion; the difference lying here, that the one is more free and mental, the other more corporal and compulsive in its operations: but that is only to evil doers; government itself being otherwise as capable of kindness, goodness and charity, as a more private society. They weakly err, that think there is no other use of government, than correction, which is the coarsest part of it: daily experience tells us, that the care and regulation of many other affairs, more soft, and daily necessary, make up much of the greatest part of government; and which must have followed the peopling of the world, had Adam never fell, and will continue among men, on earth, under the highest attainments they may arrive at, by the coming of the blessed Second Adam,5 the Lord from heaven. Thus much of government in general, as to its rise and end. . . .

Wherefore governments rather depend upon men, than men upon governments. Let men be good, and the government cannot be bad; if it be ill, they will cure it. But, if men be bad, let the government be never so good, they will endeavor to warp and spoil it to their turn. I know some say, let us have good laws, and no matter for the men that execute them: but let them consider, that though good laws do well, good men do better: for good laws may want good men, and be abolished or evaded by ill men; but good men will never want good laws, nor suffer6 ill ones. It is true, good laws have some awe upon ill ministers, but that is where they have not power to escape or abolish them, and the people are generally wise and good: but a loose and depraved people (which is the question) love laws and an administration like themselves. That, therefore, which makes a good constitution, must keep it, viz: men of wisdom and virtue, qualities, that because they descend not with worldly inheritances, must be carefully propagated by a virtuous education of youth; for which after ages will owe more to the care and prudence of founders, and the successive magistracy, than to their parents, for their private patrimonies. . . .

Back to TopPennsylvania: An Act for Freedom of Conscience, 16827

Whereas the glory of almighty God and the good of mankind is the reason and end of government and, therefore, government in itself is a venerable ordinance of God. And forasmuch as it is principally desired and intended by the Proprietary8 and Governor and the freemen of the province of Pennsylvania and territories thereunto belonging to make and establish such laws as shall best preserve true Christian and civil liberty in opposition to all unchristian, licentious, and unjust practices, whereby God may have his due, Caesar his due,9 and the people their due, from tyranny and oppression on the one side and insolence and licentiousness on the other, so that the best and firmest foundation may be laid for the present and future happiness of both the Governor and people of the province and territories aforesaid and their posterity.

Be it, therefore, enacted by William Penn, Proprietary and Governor, by and with the advice and consent of the deputies of the freemen of this province and counties aforesaid in assembly met and by the authority of the same, that these following chapters and paragraphs shall be the laws of Pennsylvania and the territories thereof.

Chap. i. Almighty God, being only Lord of conscience, father of lights and spirits, and the author as well as object of all divine knowledge, faith, and worship, who can only enlighten the mind and persuade and convince the understandings of people, in due reverence to his sovereignty over the souls of mankind:

Be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, that no person now or at any time hereafter living in this province, who shall confess and acknowledge one almighty God to be the creator, upholder, and ruler of the world, and who professes him or herself obliged in conscience to live peaceably and quietly under the civil government, shall in any case be molested or prejudiced for his or her conscientious persuasion or practice. Nor shall he or she at any time be compelled to frequent or maintain any religious worship, place, or ministry whatever contrary to his or her mind, but shall freely and fully enjoy his, or her, Christian liberty in that respect, without any interruption or reflection. And if any person shall abuse or deride any other for his or her different persuasion and practice in matters of religion, such person shall be looked upon as a disturber of the peace and be punished accordingly.

But to the end that looseness, irreligion, and atheism may not creep in under pretense of conscience in this province, be it further enacted, by the authority aforesaid, that, according to the example of the primitive Christians and for the ease of the creation, every first day of the week, called the Lord’s day, people shall abstain from their usual and common toil and labor that, whether masters, parents, children, or servants, they may the better dispose themselves to read the scriptures of truth at home or frequent such meetings of religious worship abroad as may best suit their respective persuasions.

Chap. ii. And be it further enacted by, etc., that all officers and persons commissioned and employed in the service of the government in this province and all members and deputies elected to serve in the Assembly thereof and all that have a right to elect such deputies shall be such as profess and declare they believe in Jesus Christ to be the son of God, the savior of the world, and that are not convicted of ill-fame or unsober and dishonest conversation and that are of twenty-one years of age at least.

Chap. iii. And be it further enacted, etc., that whosoever shall swear in their common conversation by the name of God or Christ or Jesus, being legally convicted thereof, shall pay, for every such offense, five shillings or suffer five days imprisonment in the house of correction at hard labor to the behoove of the public and be fed with bread and water only during that time.

Chap. v. And be it further enacted, etc., for the better prevention of corrupt communication, that whosoever shall speak loosely and profanely of almighty God, Christ Jesus, the Holy Spirit, or the scriptures of truth, and is legally convicted thereof, shall pay, for every such offense, five shillings or suffer five days imprisonment in the house of correction at hard labor to the behoove of the public and be fed with bread and water only during that time.

Chap. vi. And be it further enacted, etc., that whosoever shall, in their conversation, at any time curse himself or any other and is legally convicted thereof shall pay for every such offense five shillings or suffer five days imprisonment as aforesaid.

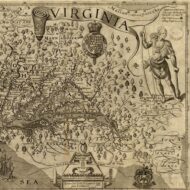

Back to TopJohn Miller, “As to their religion, they are very much divided,” 169510

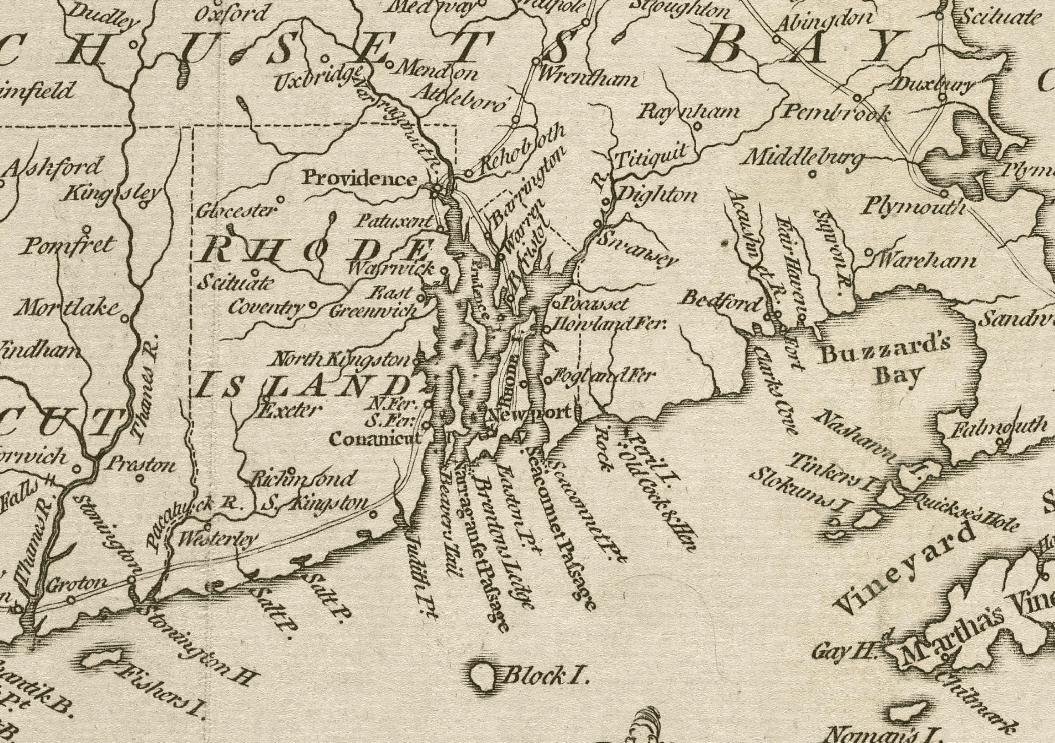

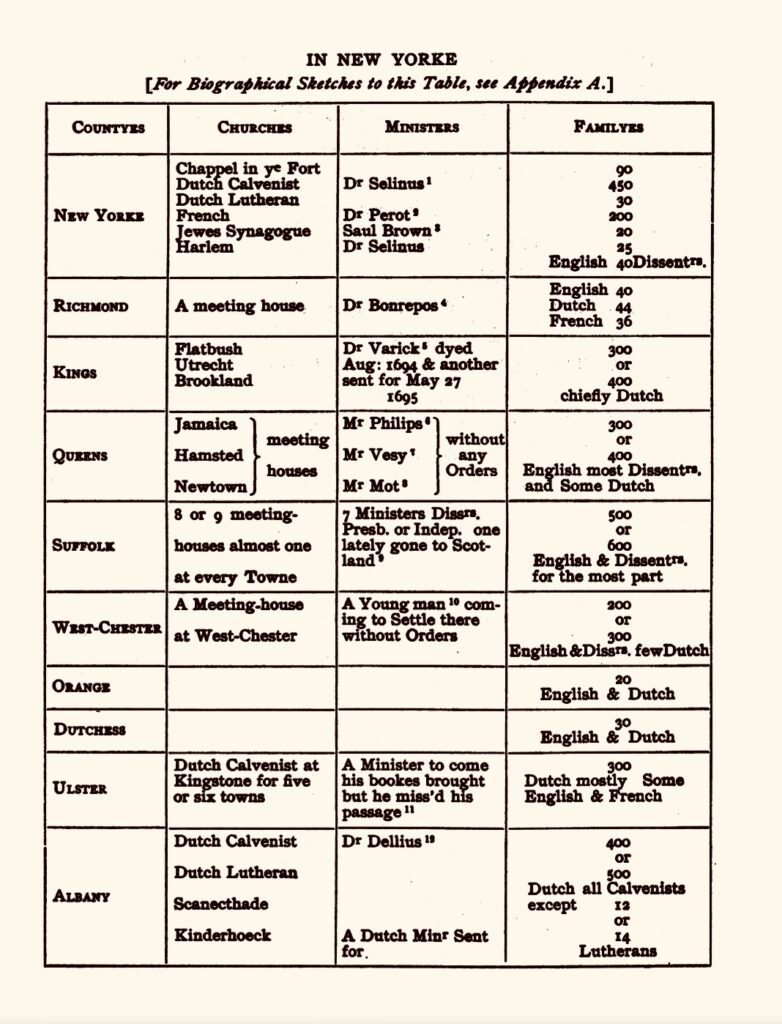

The number of the inhabitants in this province are about 3,000 families, whereof almost one half are naturally Dutch, a great part English and the rest French. Which how they are seated and what number of families of each nation what churches, meeting houses, ministers or pretended ministers there are in each County may be best discerned by the table here inserted. As to their Religion they are very much divided; few of them intelligent and sincere but the most part ignorant and conceited, fickle & regardless [sic]. . . .

Come we now to consider those things which I have said to be either wanting or obstructive to the happiness of New York, and here I shall not speak of every slight or trivial matter but only those of more considerable importance, which I count to be six: 1, the wickedness and irreligion of the inhabitants; 2, want of Ministers; 3, difference of opinions in religion; 4, a civil dissension; 5, the heathenism of the Indians; and 6, the neighborhood of Canada. . . .

The 1st. is the wickedness & irreligion of the inhabitants which abounds in all parts of the province and appears in so many shapes constituting so many sorts of sin that I can scarce tell which to begin withal. But as a great reason of and inlet to the rest I shall first mention the great negligence of divine things that is generally found in most people of what sect or party soever they pretend to be. Their eternal interests are their least concern, and as if salvation were not a matter of moment when they have opportunities of serving God, they care not for making use thereof or if they go to church, ‘tis but too often out of curiosity and to find out faults in him that preaches, rather than to hear their own—or what is yet worse, to slight and deride where they should be serious. If they have none of those opportunities they are well contented and regard it little . . . for though at first they will pretend to have a great regard for God’s ordinances and a high esteem for the Ministry whether real or pretended a little time will plainly evidence that they were more pleased at the novelty than truly affected with the benefit. . . . In a soil so rank as this no marvel if the Evil one find a ready entertainment for the seed he is minded to cast in and from a people so inconstant and regardless of Heaven and holy things[!] No wonder if God withdraw his grace and give them up a prey to those temptations which they so industriously seek to embrace. Hence is it, therefore, that their natural corruption without check or hindrance is by frequent acts improved into habits most evil in the practice and difficult in the correction. . . .

Now in New York there are either:

- No ministers at all, that is of the settled and established religion of the nation. And of such there is not oftentimes one in the whole province nor at any time except the chaplain to his Majesty’s forces in N. York that does discharge or pretend to discharge the duty of a minister and he being but one cannot do it everywhere nay, but in very few places. . . . It happens also that he is often changed, which is not without its inconveniences but proves very prejudicial to religion in many cases as is easy to instance. Besides, while he does his duty among them he shall experience their gratitude but very little, and be sure to meet with a great many discouragements except instead of reprehending and correcting he will connive at and soothe people in their sinful courses.

- Or secondly, if there by any ministers, they are such as only call themselves so and are but pretended Ministers. Many of them have no orders at all but set up for themselves of their own head and authority. Or if they have orders, are Presbyterians, Independents, etc. Now all these have no other encouragement for the pains they pretend to take than the voluntary contributions of the people or at best a salary by agreement and subscription which yet they shall not enjoy, except they take more care to please the humors and delight the fancies of their hearers than to preach up true religion and a Christian life. Hence it comes to pass that the people live very loosely and they themselves very poorly at best, if they are not forced for very necessity and by the malice of some of their hearers to forsake their congregations besides being of different persuasions and striving to settle such sentiments as they indulge themselves in, in the hearts of those who are under their ministry they do more harm in distracting and dividing ye people than good in the amending their lives and conversations.

- Or thirdly if there be or have been any ministers and those ministers, they have been here and are in other Provinces many of them such as being of a vicious life and conversation have played so many vile pranks and shown such an ill light as has been very prejudicial to religion in general & the Church of England in particular, or else they have been such as tho’ sober yet have been very young, and so instead of doing good have been easily drawn into the commission of evil and become as scandalous as those last mentioned. . . .

The Province of New York being peopled by several nations, there are manifold and different opinions of religion among them as to which though there are but very few of any sect who are either real or intelligent yet several of the partisans of each sort have every one such a desire of being uppermost and increasing the number of their own party that they not only thereby make themselves unhappy by destroying true piety and setting up instead thereof a fond heat and blind zeal for they know not what, but also industriously obstruct the settlement of the established religion of the nation which only can make them happy and have hitherto either by their craft & cunning or their money prospered in their designs and to do thus they have but too much pretense from the scandalous lives of some ministers the matter considered under the former head. . . .

The great, most proper, and as I conceive effectual means to remedy and prevent all the disorders I have already mentioned and promote the settlement & improvement of religion and unity both among the English subjects that are already Christians and the Indians supposed to be made so is that his Majesty will graciously please to send over a Bishop to the Province of New York who, if duly qualified, empowered and settled, may with the assistance of a small force for the subduing of Canada by God’s grace and blessing be author of great happiness not only to New York in particular but to all the English plantations on that part of the continent of America in general. . . .

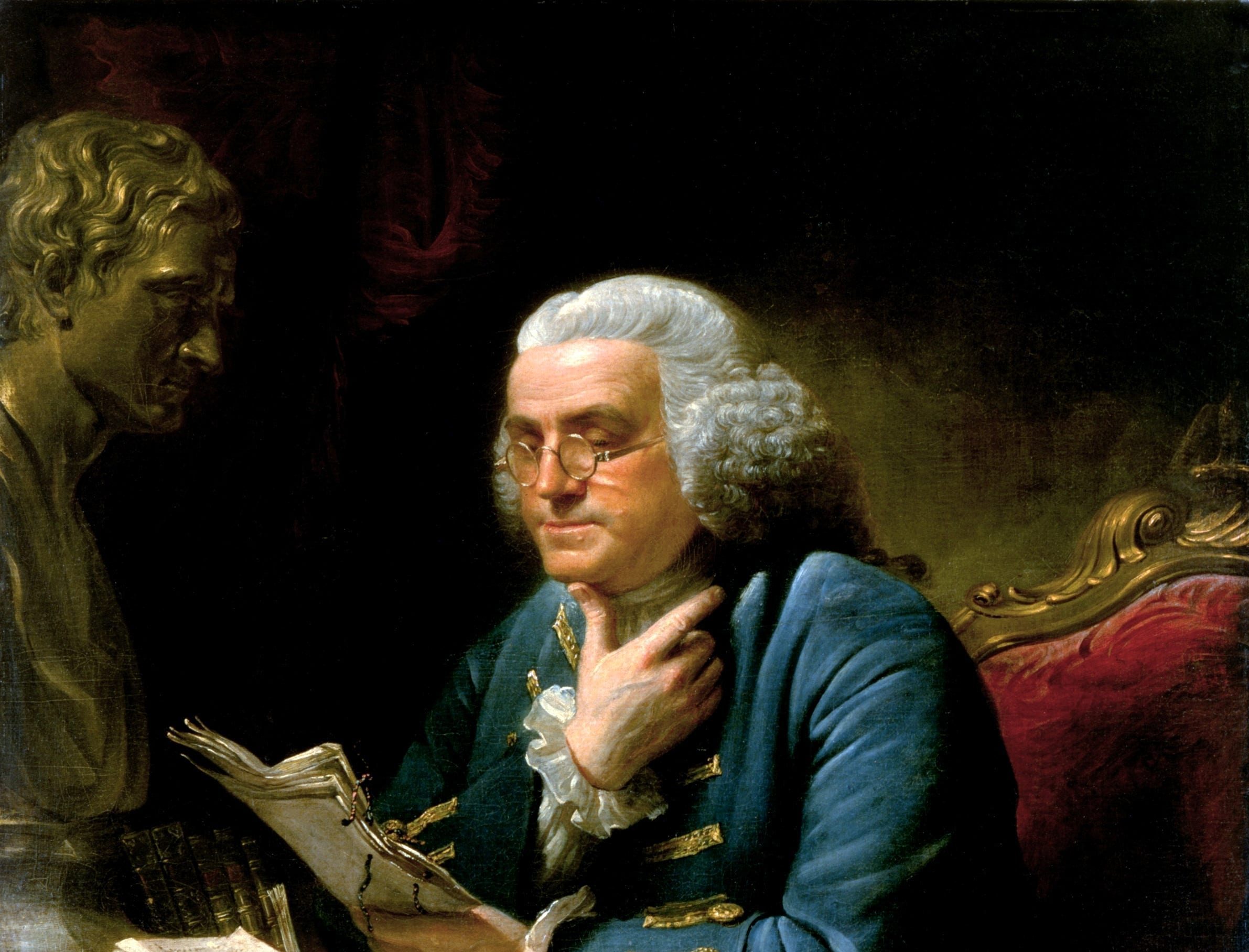

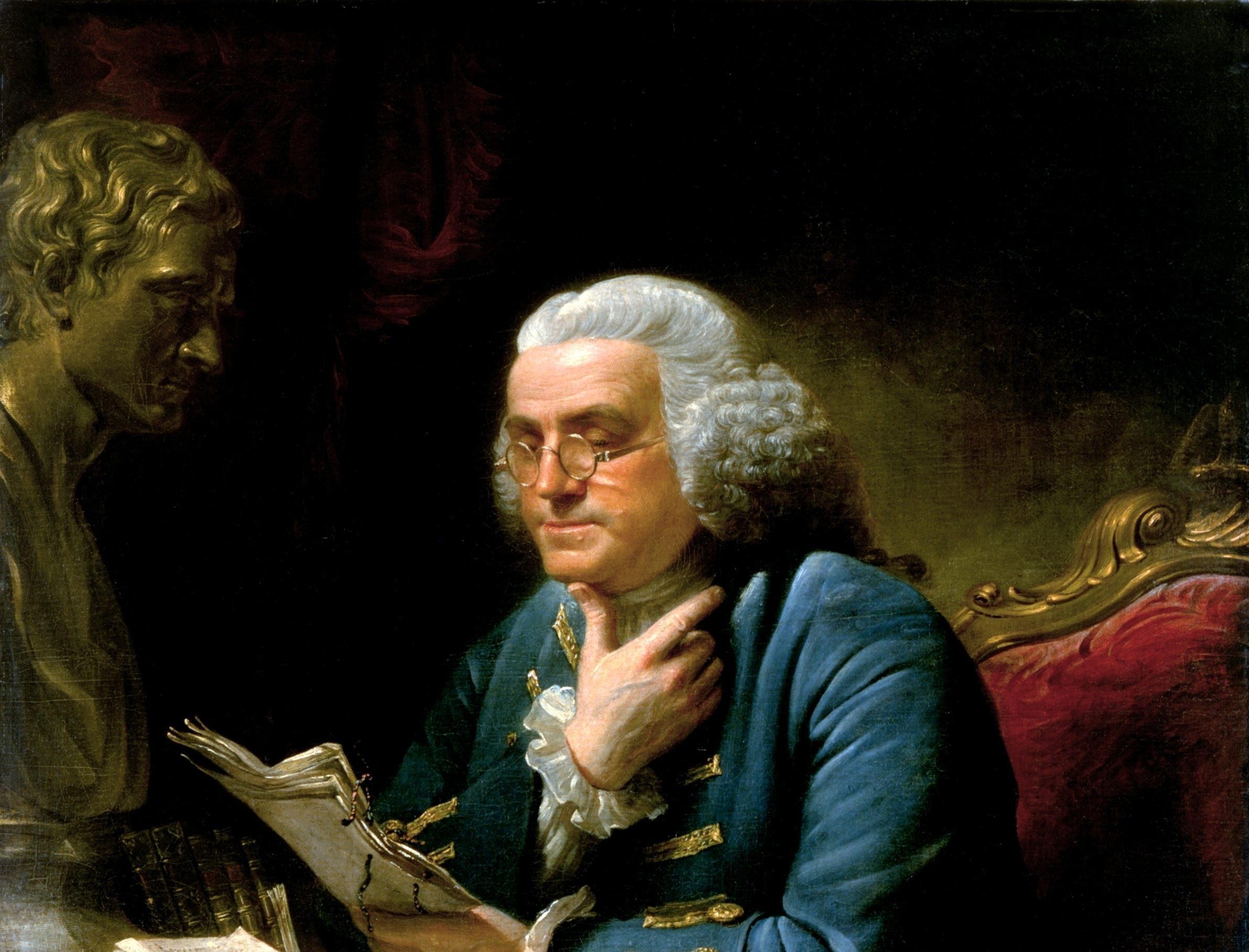

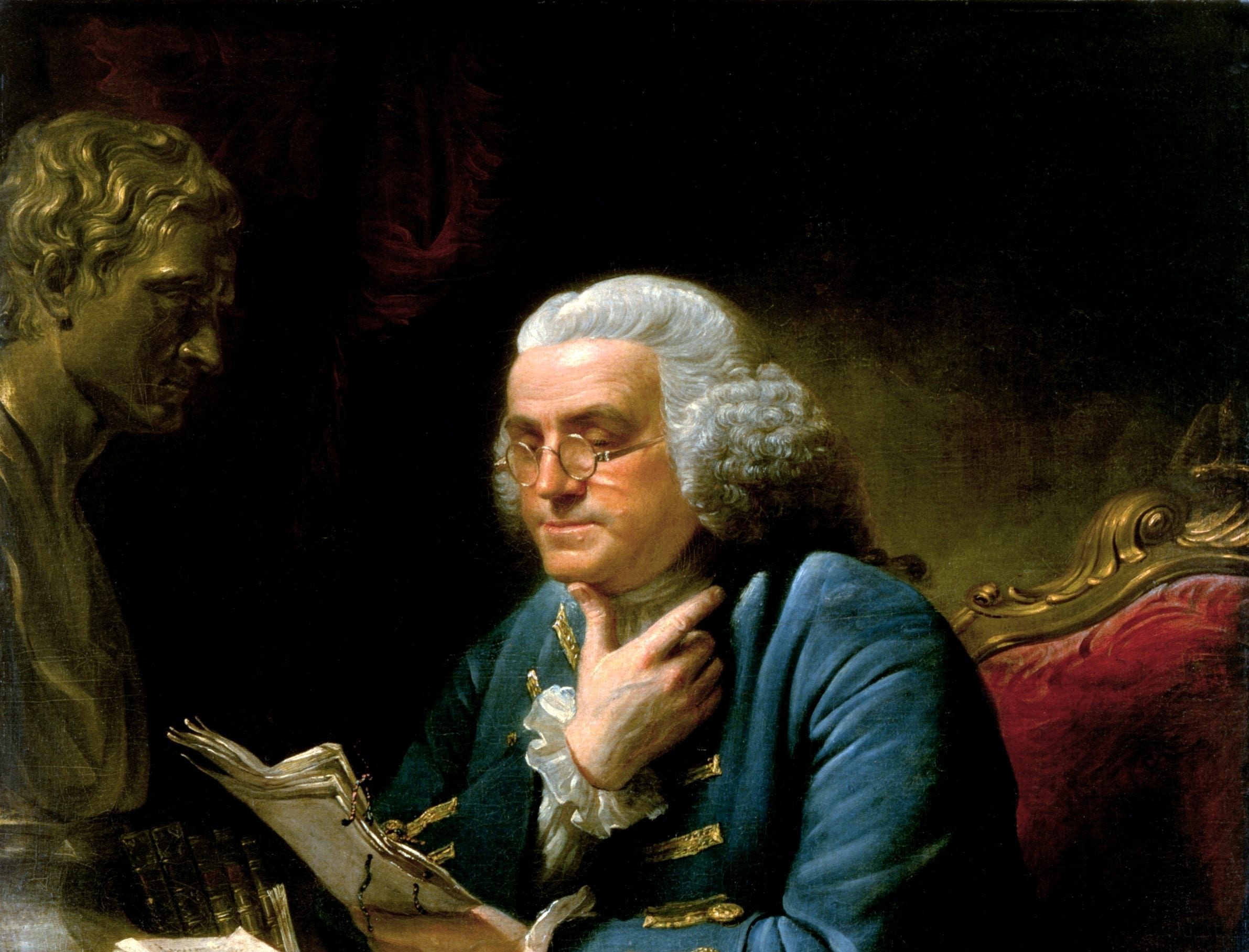

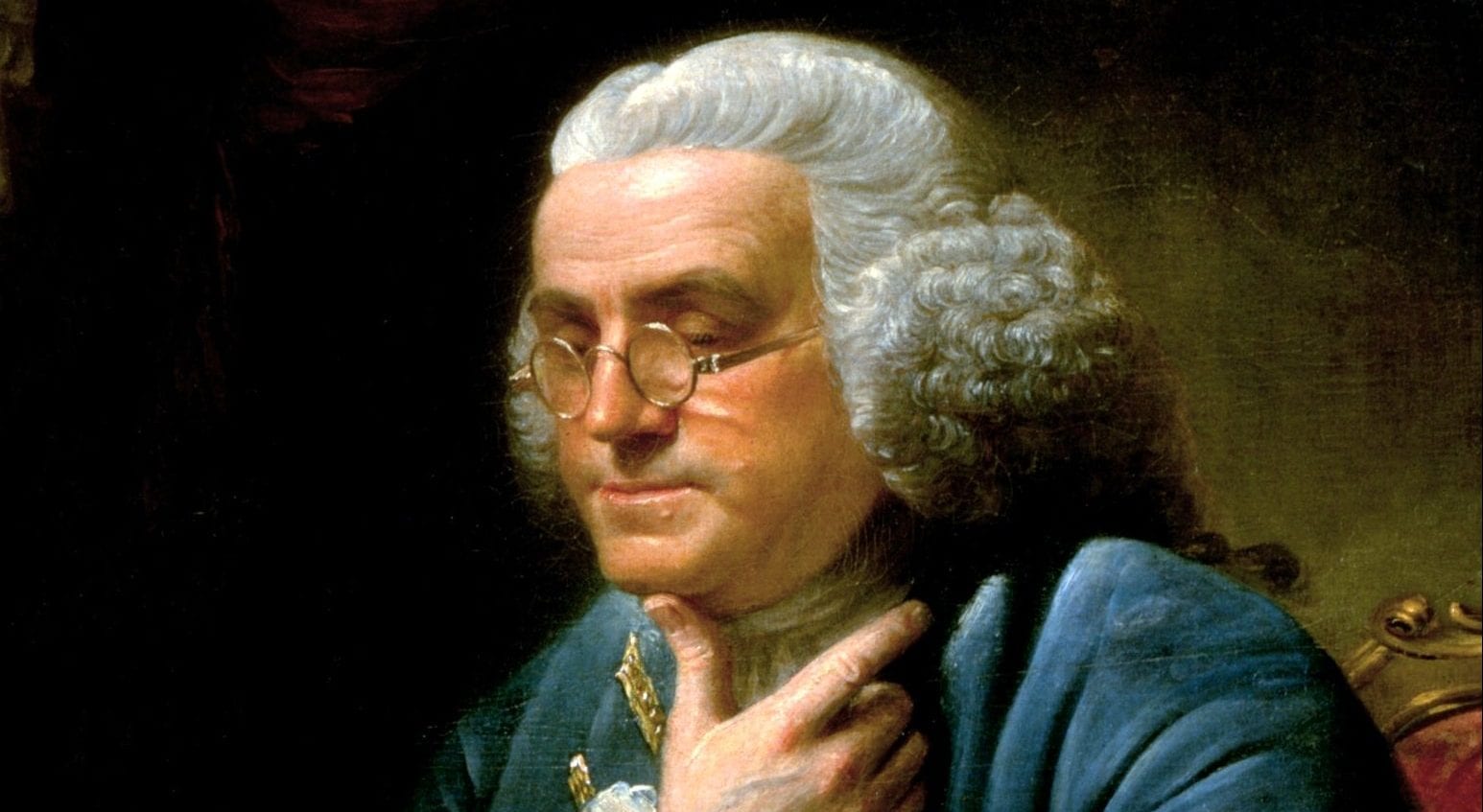

Back to TopBenjamin Franklin, George Whitefield Preaches in Philadelphia, 173911

In 1739, arrived among us from England the Rev. Mr. Whitefield, who had made himself remarkable there as an itinerant preacher. He was at first permitted to preach in some of our churches; but the clergy taking a dislike to him, soon refused him their pulpits and he was obliged to preach in the fields. The multitudes of all sects and denominations that attended his sermons were enormous and it was [a] matter of speculation to me who was one of the number, to observe the extraordinary influence of his oratory on his hearers, and how much they admired and respected him, notwithstanding his common abuse of them, by assuring them they were naturally half beasts and half devils. It was wonderful to see the change soon made in the manners of our Inhabitants; from being thoughtless or indifferent about religion, it seemed as if all the world were growing religious; so that one could not walk through the town in an evening without hearing psalms sung in different families of every street.

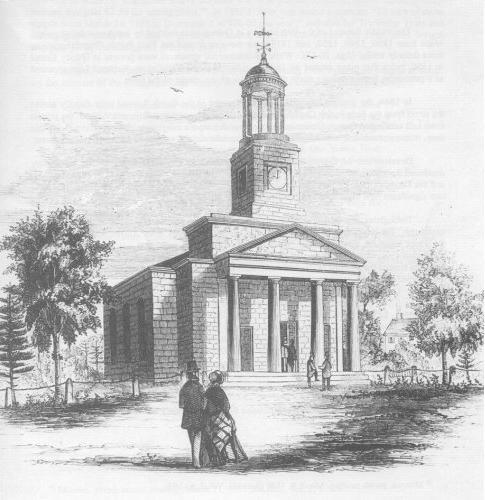

And it being found inconvenient to assemble in the open air, subject to its inclemencies, the building of a house to meet in was no sooner proposed and persons appointed to receive contributions, but sufficient sums were soon received to procure the ground and erect the building, which was 100 feet long and 70 broad, about the size of Westminster Hall, and the work was carried on with such spirit as to be finished in a much shorter time than could have been expected. Both house and ground were vested in Trustees, expressly for the use of any preacher of any religious persuasion who might desire to say something to the people of Philadelphia, the design in building not being to accommodate any particular sect, but the inhabitants in general, so that even if the Mufti of Constantinople were to send a missionary to preach Mahometism to us, he would find a pulpit at his service. . . .

I happened soon after to attend one of [Whitefield’s] sermons, in the course of which I perceived he intended to finish with a collection, and I silently resolved he should get nothing from me. I had in my pocket a handful of copper money, three or four silver dollars, and five pistoles in Gold. As he proceeded I began to soften, and concluded to give the coppers. Another stroke of his oratory made me ashamed of that, and determined me to give the silver; and he finished so admirably, that I emptied my pocket wholly into the collector’s dish, gold and all. . . .

He had a loud and clear voice, and articulated his words and sentences so perfectly that he might be heard and understood at a great Distance, especially as his auditors, however numerous, observed the most exact silence. He preached one evening from the top of the Court House steps, which are in the middle of Market Street, and on the West Side of Second Street which crosses it at right angles. Both Streets were filled with his Hearers to a considerable distance. Being among the hindmost in Market Street, I had the curiosity to learn how far he could be heard, by retiring backwards down the Street towards the River; and I found his voice distinct till I came near Front Street, when some noise in that Street, obscured it. Imagining then a semicircle, of which my distance should be the radius, and that it were filled with Auditors, to each of whom I allowed two square feet, I computed that he might well be heard by more than thirty thousand. This reconciled me to the newspaper accounts of his having preached to 25,000 People in the fields, and to the ancient histories of generals haranguing whole armies, of which I had sometimes doubted. . . .

Elisha Williams, The Essential Rights and Liberties of Protestants, 174412

. . . That the sacred scriptures are the alone rule of faith and practice to a Christian, all Protestants are agreed in; and must therefore inviolably maintain, that every Christian has a right of judging for himself what he is to believe and practice in religion according to that rule: Which I think on a full examination you will find perfectly inconsistent with any power in the civil magistrate to make any penal laws in matters of religion. Tho’ Protestants are agreed in the profession of that principle, yet too many in practice have departed from it. The evils that have been introduced thereby into the Christian church are more than can be reckoned up. Because of the great importance of it to the Christian and to his standing fast in that liberty wherewith Christ has made him free, you will not fault me if I am the longer upon it. The more firmly this is established in our minds; the more firm shall we be against all attempts upon our Christian liberty, and better practice that Christian charity towards such as are of different sentiments from us in religion that is so much recommended and inculcated in those sacred oracles, and which a just understanding of our Christian rights has a natural tendency to influence us to. . . .

The members of a civil state or society do retain their natural liberty in all such cases as have no relation to the ends of such a society. . . . Should a government therefore restrain the free use of the scriptures, prohibit men the reading of them, and make it penal to examine and search them; it would be a manifest usurpation upon the common rights of mankind, as much a violation of natural liberty as the attack of a highwayman upon the road can be upon our civil rights. And indeed with respect to the sacred writings, men might not only read them if the government did prohibit the same, but they would be bound by a higher authority to read them, notwithstanding any humane prohibition. The pretense of any authority to restrain men from reading the same, is wicked as well as vain. . . .

II. The members of a civil state do retain their natural liberty or right of judging for themselves in matters of religion. Every man has an equal right to follow the dictates of his own conscience in the affairs of religion. Everyone is under an indispensable obligation to search the scripture for himself (which contains the whole of it) and to make the best use of it he can for his own information in the will of God, the nature and duties of Christianity. And as every Christian is so bound; so he has an unalienable right to judge of the sense and meaning of it, and to follow his judgment wherever it leads him; even an equal right with any rulers be they civil or ecclesiastical. This I say, I take to be an original right of the human nature, and so far from being given up by the individuals of a community that it cannot be given up by them if they should be so weak as to offer it. Man by his constitution as he is a reasonable being capable of the knowledge of his Maker; is a moral & accountable being: and therefore as everyone is accountable for himself, he must reason, judge and determine for himself. That faith and practice which depends on the judgment and choice of any other person, and not on the person’s own understanding judgment and choice, may pass for religion in the synagogue of Satan, whose tenet is that ignorance is the mother of devotion; but with no understanding Protestant will it pass for any religion at all. No action is a religious action without understanding and choice in the agent. Whence it follows, the rights of conscience are sacred and equal in all, and strictly speaking unalienable. This right of judging every one for himself in matters of religion results from the nature of man, and is so inseparably connected therewith, that a man can no more part with it than he can with his power of thinking: and it is equally reasonable for him to attempt to strip himself of the power of reasoning, as to attempt the vesting of another with this right. And whoever invades this right of another, be he pope or Cæsar, may with equal reason assume the other’s power of thinking, and so level him with the brutal creation. A man may alienate some branches of his property and give up his right in them to others; but he cannot transfer the rights of conscience, unless he could destroy his rational and moral powers, or substitute some other to be judged for him at the tribunal of God.

But what may further clear this point and at the same time shew the extent of this right of private judgment in matters of religion, is this truth, that the sacred scriptures are the alone rule of faith and practice to every individual Christian. Were it needful I might easily show the sacred scriptures have all the characters necessary to constitute a just and proper rule of faith and practice, and that they alone have them. It is sufficient for all such as acknowledge the divine authority of the scriptures, briefly to observe, that God the author has therein declared he has given and designed them to be our only rule of faith and practice. Thus says the apostle Paul, 2 Tim. 3. 15, 16; That they are given by Inspiration from God, and are profitable for Doctrine, for Reproof, for Correction, for Instruction in Righteousness; that the Man of God may be perfect, thoroughly furnished unto every good Work. . . . Now inasmuch as the scriptures are the only rule of faith and practice to a Christian; hence every one has an unalienable right to read, enquire into, and impartially judge of the sense and meaning of it for himself. For if he is to be governed and determined therein by the opinions and determinations of any others, the scriptures cease to be a rule to him, and those opinions or determinations of others are substituted in the room thereof. . . .

Back to TopGottlieb Mittelberger, “Liberty in Pennsylvania is more hurtful than useful,” 175013

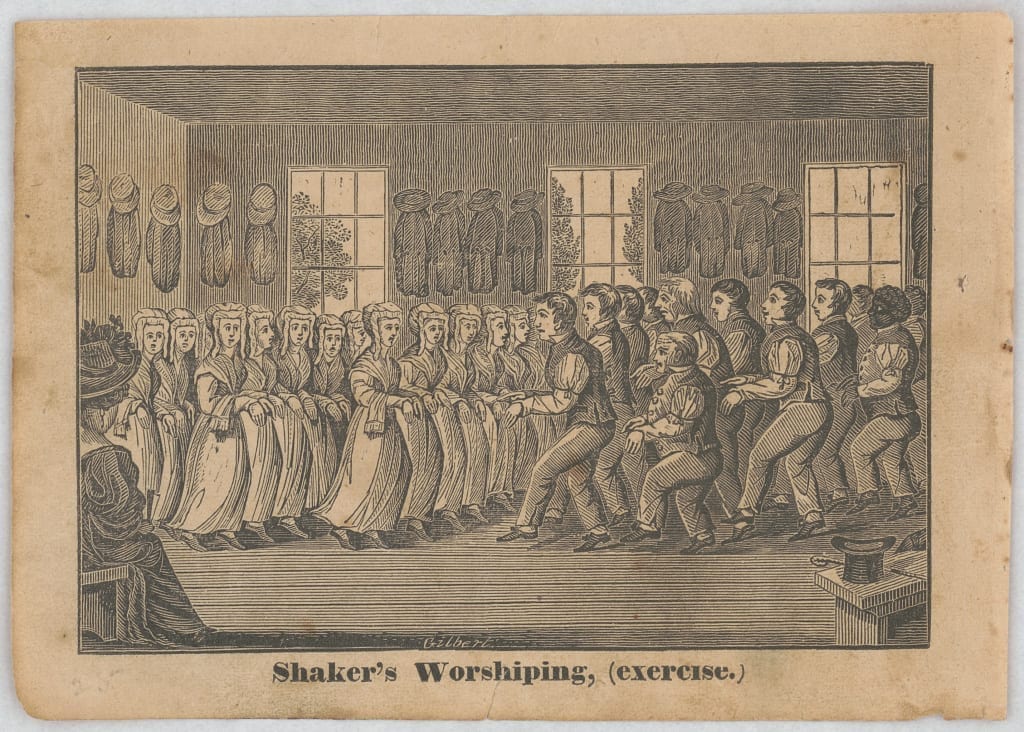

For there are many doctrines of faith and sects in Pennsylvania which cannot all be enumerated, because many a one will not confess to what faith he belongs.

Besides, there are many hundreds of adult persons who have not been and do not even wish to be baptized. There are many who think nothing of the sacraments and the Holy Bible, nor even of God and his word. Many do not even believe that there is a true God and devil, a heaven and a hell, salvation and damnation, a resurrection of the dead, a judgment and an eternal life; they believe that all one can see is natural. For in Pennsylvania every one may not only believe what he will, but he may even say it freely and openly.

Consequently, when young persons, not yet grounded in religion, come to serve for many years with such free-thinkers and infidels, and are not sent to any church or school by such people, especially when they live far from any school or church. Thus, it happens that such innocent souls come to no true divine recognition, and grow up like heathens and Indians. . . .

Coming to speak of Pennsylvania again, that colony possesses great liberties above all other English colonies, inasmuch as all religious sects are tolerated there. We find there Lutherans, Reformed, Catholics, Quakers, Mennonists or Anabaptists, Herrnhuters or Moravian Brethren, Pietists, Seventh Day Baptists, Dunkers, Presbyterians, Newborn, Freemasons, Separatists, Freethinkers, Jews, Mohammedans, Pagans, Negroes and Indians. The Evangelicals and Reformed, however, are in the majority. But there are many hundred unbaptized souls there that do not even wish to be baptized. Many pray neither in the morning nor in the evening, neither before nor after meals. No devotional book, not to speak of a Bible, will be found with such people. In one house and one family, 4, 5, and even 6 sects may be found. . . .

The preachers throughout Pennsylvania have no power to punish any one, or to compel any one to go to church; nor has anyone a right to dictate to the other, because they are not supported by any Consistorio. Most preachers are hired by the year like cowherds in Germany; and if one does not preach to their liking, he must expect to be served with a notice that his services will no longer be required. It is, therefore, very difficult to be a conscientious preacher, especially as they have to hear and suffer much from so many hostile and often wicked sects. The most exemplary preachers are often reviled, insulted, and scoffed at like the Jews, by the young and old, especially in the country. I would, therefore, rather perform the meanest herdsman’s duties in Germany than be a preacher in Pennsylvania. Such unheard-of rudeness and wickedness spring from the excessive liberties of the land, and from the blind zeal of the many sects. To many a one’s soul and body, liberty in Pennsylvania is more hurtful than useful. There is a saying in that country: Pennsylvania is the heaven of the farmers, the paradise of the mechanics, and the hell of the officials and preachers.

- 1. In Donald S. Lutz, Colonial Origins of the American Constitution: A Documentary History, ed. Donald S. Lutz (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund 1998).

- 2. Paul.

- 3. I Timothy 1: 9-10.

- 4. Romans 13: 1-5.

- 5. A reference to Christ, I Corinthians 15: 45.

- 6. The words "want" and "suffer" carry the older meanings of "lack" and "allow," respectively.

- 7. In Donald S. Lutz, Colonial Origins of the American Constitution: A Documentary History, ed. Donald S. Lutz (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund 1998). As Lutz points out, the sections are misnumbered in the original and there is no Section iv.

- 8. The Penn family, which owned Pennsylvania. It was given to William Penn by King Charles II in 1681 to pay off a debt.

- 9. An allusion to a saying of Jesus quoted in all the synoptic gospels: Matthew 22:21, Mark 12:17, and Luke 20:25. In each version of the story, Jesus resolves a dilemma posed by the Roman requirement that the Jews pay taxes to Caesar.

- 10. John Miller, "New Yorke Considered and Improved" (1695), ed. Victor Hugo Paltsits and Paul Royster. Electronic Texts in American Studies 17, pp. 40, 56, 64-67, 74-74.

- 11. Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography (Henry Holt and Co: New York, 1916), 78-80.

- 12. Elisha Williams, The Essential Rights and Liberties of Protestants (1744). Elisha Williams (1694–1755) was a Congregational minister active in colonial politics.

- 13. Gottlieb Mittelberger, Journey to Pennsylvania in the Year 1750, Carl Theo. Eben, trans. (Philadelphia: John Jos. McVey, 1898), 31-32, 54-55, 62-63. Gottlieb Mittelberger (1714–1758) was a Lutheran pastor in Pennsylvania for several years in the early 1750s.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.