Introduction

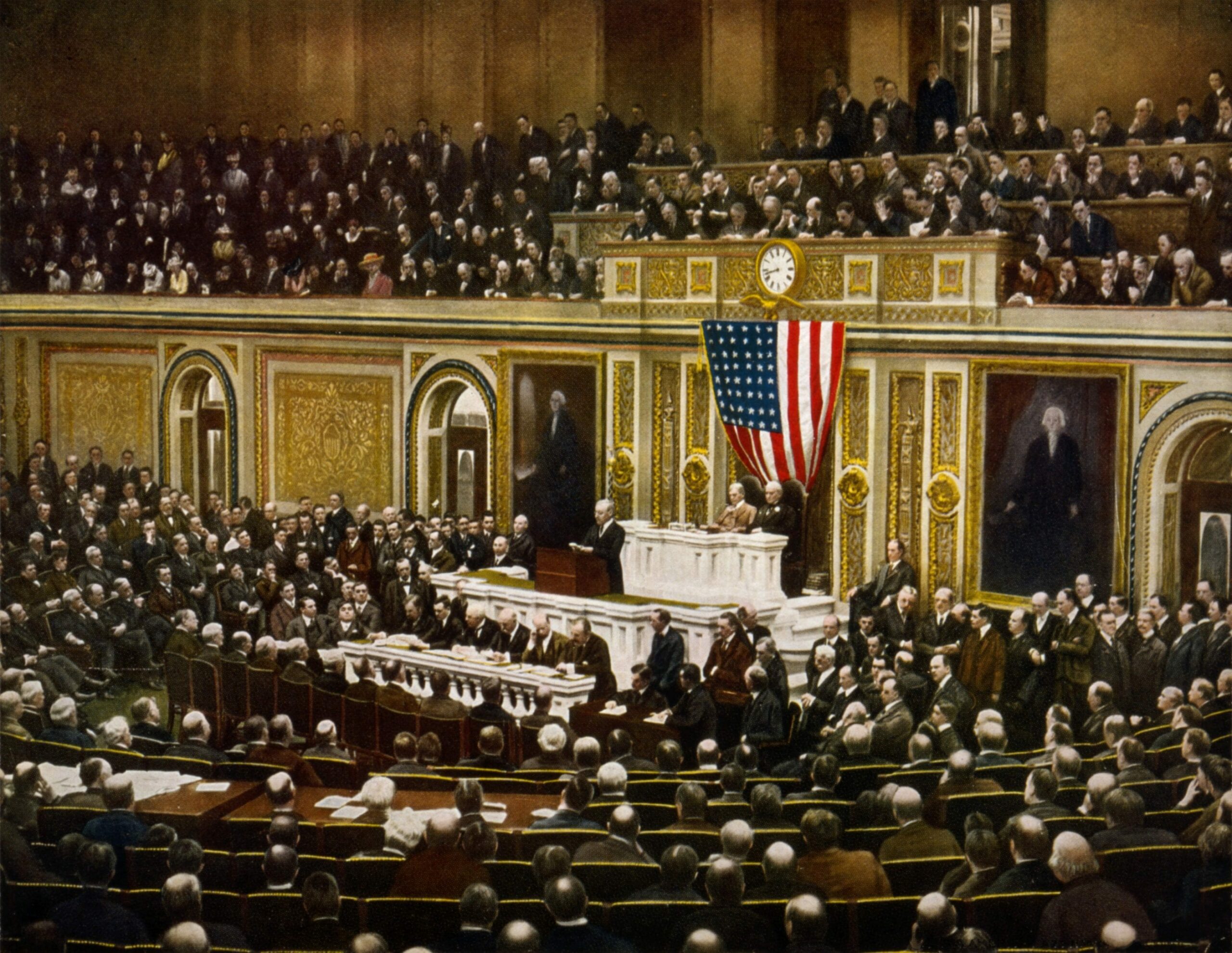

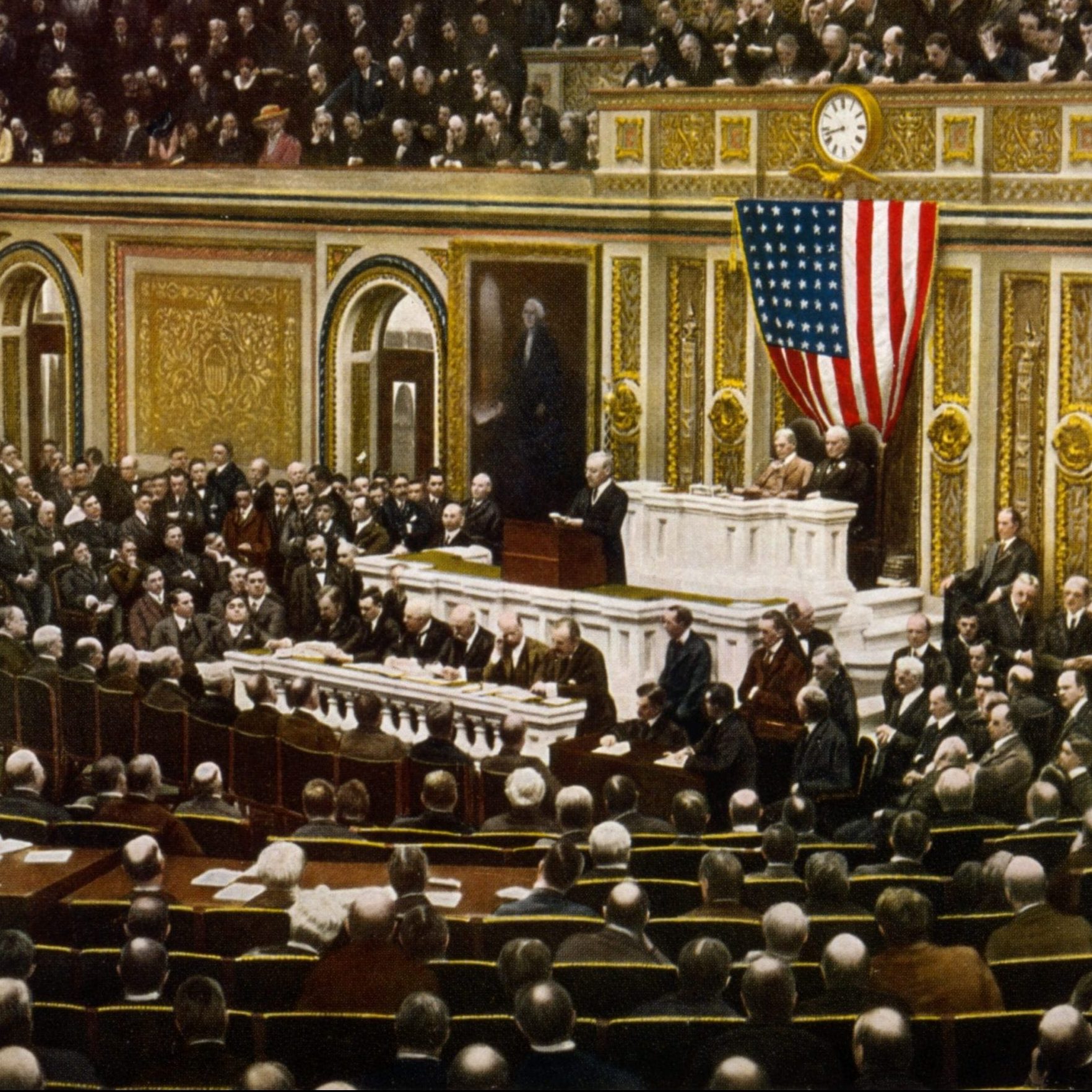

In Constitutional Government in the United States, published just four years prior to winning the 1912 presidential election, Woodrow Wilson offered his thoughts on the American political system as a whole, including his famous discussion of the “Newtonian” versus “Darwinian” theory of constitutional interpretation. Although he had focused more on Congress in his early work (see “Cabinet Government in the United States” and Congressional Government), by 1908 Wilson had come to see the presidency as the key institution in American politics, which was capable of overcoming the deficiencies of the Congress. This book was written at the height of party strength in Congress, and Wilson describes the power of party leaders, especially in the House of Representatives. Whereas Wilson described Congress as dominated by committees in his earlier book, he now saw it was a party-dominated body, a situation that he lamented.

Wilson’s vision for the future of American government emphasized the evolving nature of the Constitution. He saw it as a document that could operate differently depending on how it is interpreted. His preferred interpretation of the Constitution would focus on how people in government could coordinate their activities to work together, rather than check and balance each other in a system that tended towards gridlock. Wilson notes that Congress developed its own internal leaders, in both the House and the Senate, over the late nineteenth century (see “Rules of the House of Representatives” and “Obstructions in the National House” and “A Deliberative Body”), and he explains how these leaders came to acquire their power. But Wilson looks forward to a future where the president, rather than internal party leaders in Congress, would drive the legislative agenda.

Source: Woodrow Wilson, Constitutional Government in the United States (New York: Columbia University Press, 1908).

Chapter III: The President of the United States

It is difficult to describe any single part of a great governmental system without describing the whole of it. Governments are living things and operate as organic wholes. Moreover, governments have their natural evolution and are one thing in one age, another in another. The makers of the Constitution constructed the federal government upon a theory of checks and balances which was meant to limit the operation of each part and allow to no single part or organ of it a dominating force; but no government can be successfully conducted upon so mechanical a theory. Leadership and control must be lodged somewhere. . . .

The government of the United States was constructed upon the Whig[1] theory of political dynamics, which was a sort of unconscious copy of the Newtonian theory of the universe. In our own day, whenever we discuss the structure or development of anything, whether in nature or in society, we consciously or unconsciously follow Mr. Darwin[2]; but before Mr. Darwin, they followed Newton[3]. . . .

In brief, as Montesquieu pointed out to them in his lucid way, . . . [British eighteenth-century politicians] had sought to balance executive, legislature, and judiciary off against one another by a series of checks and counterpoises, which Newton might readily have recognized as suggestive of the mechanism of the heavens.

The makers of our federal Constitution followed the scheme as they found it expounded in Montesquieu, followed it . . . with genuine scientific enthusiasm. The admirable expositions of The Federalist read like thoughtful applications of Montesquieu[4] to the political needs and circumstances of America. They are full of the theory of checks and balances. . . .

The trouble with the theory is that government is not a machine, but a living thing. It falls, not under the theory of the universe, but under the theory of organic life. It is accountable to Darwin, not to Newton. It is modified by its environment, necessitated by its tasks, shaped to its functions by the sheer pressure of life. No living thing can have its organs offset against each other as checks, and live. . . . Their cooperation is indispensable, their warfare fatal. There can be no successful government without leadership or without the intimate, almost instinctive, coordination of the organs of life and action. This is not theory, but fact, and displays its force as fact, whatever theories may be thrown across its track. Living political constitutions must be Darwinian in structure and in practice.

Fortunately, the definitions and prescriptions of our constitutional law, though conceived in the Newtonian spirit and upon the Newtonian principle, are sufficiently broad and elastic to allow for the play of life and circumstance. . . .

The makers of the Constitution seem to have thought of the President as what the stricter Whig theorists wished the king to be: only the legal executive, the presiding and guiding authority in the application of law and the execution of policy. . . . As a matter of fact he has become very much more. He has become the leader of his party and the guide of the nation in political purpose, and therefore in legal action. The constitutional structure of the government has hampered and limited his action in these significant roles, but it has not prevented it. . . . It is merely the proof that our government is a living, organic thing, and must, like every other government, work out the close synthesis of active parts which can exist only when leadership is lodged in some one man or group of men. . . .

Chapter IV: The House of Representatives

. . . The House and Senate are naturally un[a]like. They are different both in constitution and character. They do not represent the same things. The House of Representatives is by intention the popular chamber, meant to represent the people by direct election through an extensive suffrage, while the Senate was designed to represent the states as political units, as the constituent members of the Union. The terms of membership in the two houses, moreover, are different. The two chambers were unquestionably intended to derive their authority from different sources and to speak with different voices in affairs. . . .

Perhaps the contrast between them is in certain respects even sharper and clearer now than in the earlier days of our history, when the House was smaller and its functions simpler. The House once debated; now it does not debate. It has not the time. There would be too many debaters, and there are too many subjects of debate. It is a business body, and it must get its business done. When the late Mr. Reed[5] once, upon a well-known occasion, thanked God that the House was not a deliberate assembly, there was no doubt a dash of half-cynical humor in the remark, such as so often gave spice and biting force to what he said, but there was the sober earnest of a serious man of affairs, too. . . .

A numerous body like the House of Representatives is naturally and of course unfit for organic, creative action through debate. . . . It organizes itself, therefore, into committees—not occasional committees, formed from time to time, but standing committees permanently charged with its business and given every prerogative of suggestion and explanation, in order that each piece of legislative business may be systematically attended to by a body small enough to digest and perfect it. . . .[6]

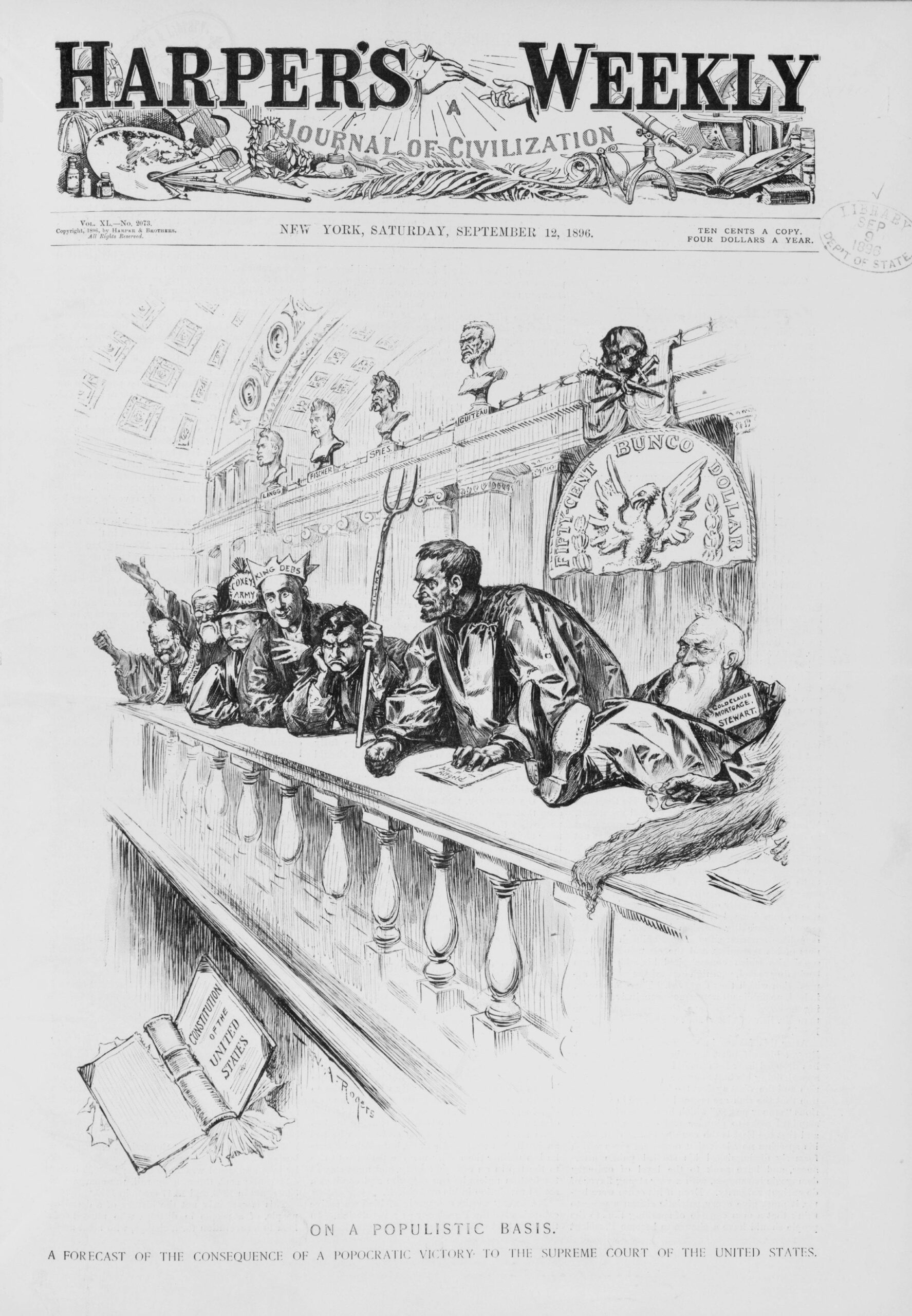

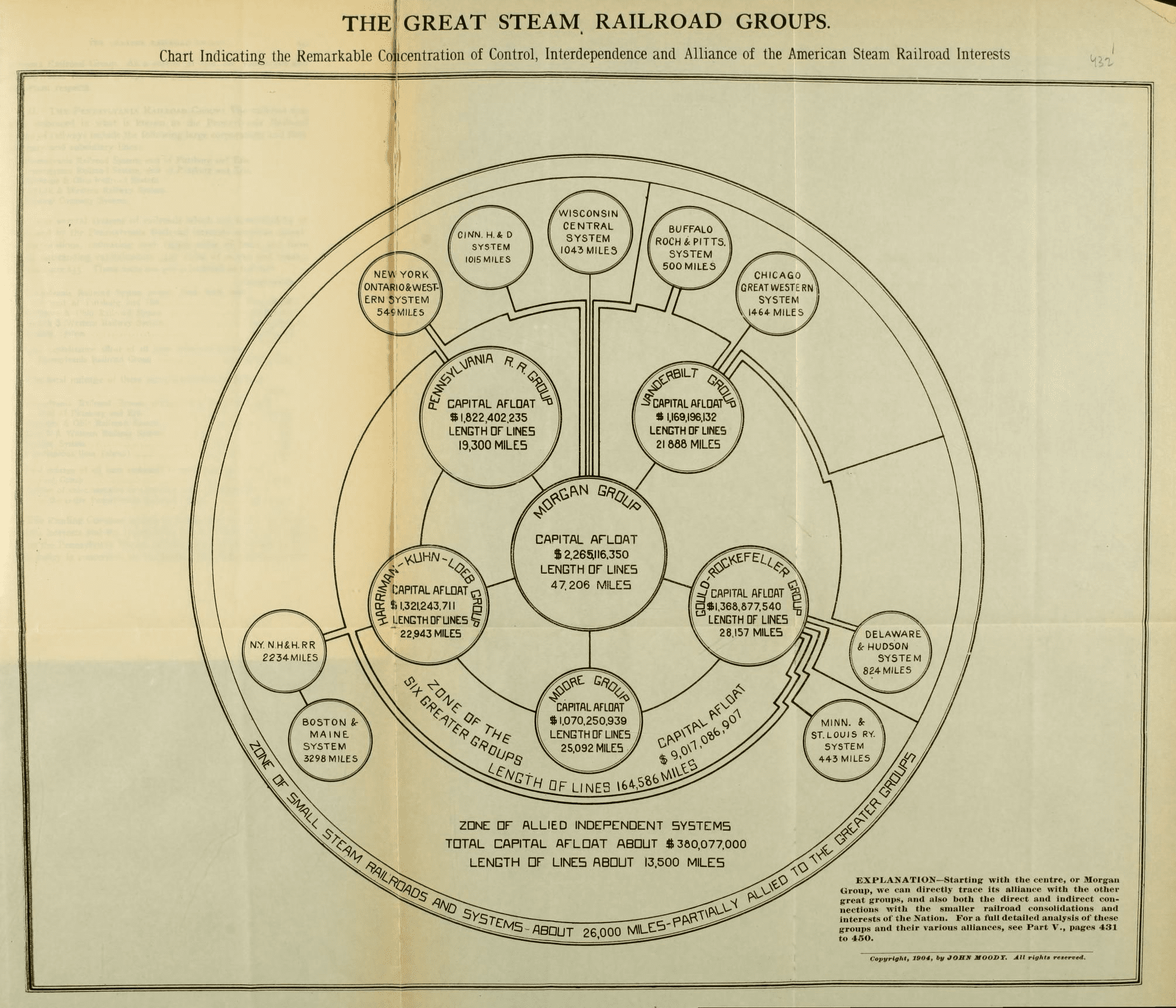

The very complexity and bulk of all this machinery is itself burdensome to the House. There are now more than half as many committees in the House as there are members in the Senate. It cannot itself choose so many committees; it cannot even follow so many. It therefore entrusts every appointment to the Speaker, and, when its business gets entangled amongst the multitude of committees and reports, follows a steering committees, which it calls the Committee on Rules. And the power of appointing the committees, which the House has conferred upon its Speaker, makes him the almost autocratic master of its actions.

In all legislative bodies except ours the presiding officer has only the powers and functions of a chairman. He is separate from parties and is looked to be punctiliously impartial. . . . But the processes of our parliamentary development have made the Speaker of our great House of Representatives and the Speakers of our state legislatures’ party leaders in whom centers the control of all that they do. . . .

All lines of analysis come back to the Speaker, whether you speak of the organization or of the action and political power of the House. Such an organization, so systematized and so concentrated, has of course made the House of Representatives one of the most powerful pieces of our whole governmental machinery, and its Speaker, in whom its power is centered and summed up, has come to be regarded as the greatest figure in our complex system, next to the president himself. The whole powerful machinery of the great popular chamber is at his disposal, and all the country knows how effectually he can use it. . . .

We are in love with efficiency as, as a practical nation, greatly admire the complete and thorough organization of the House, its preference for action and its impatience of talk: but if every part of our political machinery is to be organized for “business,” where are counsel and criticism to come in? We never stood more in need of them than we do now. . . .

Such complications and subdivisions of machinery in the active and originative organs of the government result in its being in a very real sense leaderless. In the last [chapter] I spoke of the President as leader of his party and of the nation; but, though he clearly exercises such leadership, and exercises it with great effectiveness when he has the personal force for any originative role at all, he cannot be said to be the guide and leader of the government as a whole. Our government consists in part, as I have explained, of the House and Senate. It is in that respect contrasted with all other governments. And in each part of our subdivided government there is a distinct arrangement with regard to leadership. The Senate submits to the guidance of a small group of senators, very jealous of the independence of the body they control. The House is under the command of its Speaker. The executive is in the hands of the President, whom the houses regard, when thinking of their own powers, as an outsider, and whose advice they are apt to look upon as the advice of a rival rather than of a colleague. . .

Chapter V: The Senate

It is very difficult to form a just estimate of the Senate of the United States. . . . There was a time when we were lavish in spending our praises upon it. . . . In our own day we have been equally lavish of hostile criticism. We have suspected it of every malign purpose, fixed every unhandsome motive upon it, and at times almost cast it out of our confidence altogether. . . .

The House is an organic unit; it has been at great pains to make itself so, and to become a working body under a single unifying discipline; while the Senate is not so much an organization as a body of individuals. . . .

[The] character and purpose [of the Senate] govern its whole organization and action. It is as different from the House in organization as in character and constitutional position. Its power is not concentrated in its presiding officer as the power of the House is. On the contrary, its presiding officer is of all its constituent parts the least significant. . . .

Once or twice it has looked as if the president pro tempore were likely to accumulate powers and prerogatives which might give his office a power and authority comparable with those of the Speaker of the House of Representatives. The Senate, like the House, prepares its business through the instrumentality of standing committees, and in 1828 it conferred upon its president pro tempore the authority to appoint its committees. But in 1833, for political reasons which it is not necessary to detail here, it again changed its rule and resumed to itself the right to constitute its committees by its own choice by ballot. Again in 1837 it turned to the president pro tempore for relief and conferred upon him the power of appointment, the balloting having proved very cumbersome and burdensome; but in 1845 circumstances again compelled it to withdraw the authority. . . .

[S]ingularly enough, though he has grown in importance with the permanence of his office and has seemed once and again to be chosen as in some sense the leading representative of his party in the chamber, as the Speaker of the House is, he is not in fact the command in debate or in the direction of party tactics. The leader of the Senate is the chairman of the majority caucus.[7] Each party in the Senate finds its real, its permanent, its effective organization in its caucus, and follows the leadership, in all important parliamentary battles, of the chairman of that caucus, its organization and its leadership alike resting upon arrangements quite outside the Constitution. . . .

The caucus of each party has its Committee on Committees, appointed by its chairman, subject to the ratification of the caucus itself, and charged with the important function of selecting its party’s representatives on the standing committees. The majority caucus has, besides, its Steering Committee, similarly appointed, to which fall duties very like those of the Committee on Rules in the House.

The chairman of the majority caucus is much more nearly the counterpart of the Speaker of the House than is the president pro tempore. His influence is very great and very pervasive. Through the Committee on Committees and the Steering Committee, both of which he appoints subject to the confirmation of the caucus, he plays no small part in determining both the character and the handling of the business the Senate is called on to consider.

But the Senate is a deliberative assembly and is under no such discipline of silence and obedience to its committees as the House is . . . A bill introduced by an individual senator may be put upon the calendar, debated, and voted upon without reference to a committee at all. . . .

Moreover, the make-up of the committees of the Senate is determined much more strictly by seniority and by personal privilege and precedence than is the membership of the committees of the House, with much less regard to party lines and much more regard to personal and sectional considerations—by equitable arrangement rather than by the personal choice or individual purpose of the caucus chairmen. . . .

Indeed, the Senate is, par excellence, the chamber of debate and of individual privilege. Its discussions are often enough unprofitable, are too often marred by personal feeling and by exhibitions of private interest which taint its reputation and render the country uneasy and suspicious, but they are at least the only means the country has of clarifying public business for public comprehension.

When we turn to the question which is the central question of our whole study, the question of the coordination of the Senate with the other organs of the government and the synthesis of authority and power for common action, it at once becomes evident that such a body as I have described the Senate to be, must be very hard indeed to digest into any system. A coordination of wills, united movement under a common leadership, is of the very essence of every efficient form of government. The Senate has a very stiff will of its own, a pride of independent judgment. . . .

The President has not the same recourse when blocked by the Senate that he has when opposed by the House. When the House declines his counsel he may appeal to the nation, and if public opinion respond to his appeal the House may grow thoughtful of the next congressional elections and yield; but the Senate is not so immediately sensitive to opinion and is apt to grow, if anything, stiffer if pressure of that kind is brought to bear upon it.

But there is another course which the president may follow, and which one or two presidents of unusual political sagacity have followed, with the satisfactory results that were to have been expected. He may himself be less stiff and offish, may himself act in the true spirit of the Constitution and establish intimate relations of confidence with the Senate on his own initiative. . .

It is manifestly the duty of statesmen, with whatever branch of the government they may be associated, to study in a very serious spirit of public service the right accommodation of parts in this complex system of ours, the accommodation which will give the government its best force and synthesis in the face of the difficult counsels and perplexing tasks of regulation with which it is face to face, and no one can play the leading part in such a matter with more influence or propriety than the president. If he have character, modesty, devotion, and insight as well as force, he can bring the contending elements of the system together into a great and efficient body of common counsel.

- 1. Whig political theory was first prominent in British politics in the late seventeenth century. In opposition to the Tories, Whigs opposed absolute monarchy, preferring a system in which the representative Parliament was the predominant political power. In addition, Whigs tended to prefer a more limited government, with checks and balances keeping any one person in the government from becoming too powerful.

- 2. Charles Darwin (1809–1882) was an English biologist who famously published his theory of evolution in On the Origin of Species (1859). Darwin’s theory posits that all the parts of an organism work together, and evolve over time, to adapt to the organism’s surroundings.

- 3. Sir Isaac Newton (1643–1727) was an English physicist and mathematician who formulated the three laws of motion which serve as the foundation of modern physics. Wilson is suggesting that the system of checks and balances, preferred by the Whigs and the American Founders, was like adopting the theory of Newtonian physics, as the various branches of government counteract each other much like mechanical objects in space. Wilson is advocating a different view, following Darwin, whose work focused on the biological unity of organisms. In Wilson’s view, governments should work as unified wholes, rather than as parts that check and balance each other.

- 4. Montesquieu, or Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brede and de Montesquieu (1689–1755), was a French political philosopher who is today most well-known for his book The Spirit of the Laws, which among other things articulated the theory of separation of powers. Montesquieu profoundly affected the thought of the American Founders and the design of the U.S. Constitution. During the period when the U.S. Constitution was being written and ratified, Montesquieu’s work was cited more often in America than any other political philosopher.

- 5. Thomas Brackett Reed (1839–1902) was Speaker of the House of Representatives from 1889–1891 and 1895–1899. He was one of the most powerful speakers and is known for establishing the Reed Rules in 1890, which gave significant authority to party leaders to control proceedings in the House. For more on Reed, see "Rules of the House of Representatives" and “Obstructions in the National House” and “A Deliberative Body”.

- 6. For more on the role of committees during the late nineteenth century, see Congressional Government.

The Promise of American Life

December 31, 1909

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.