Introduction

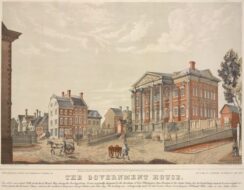

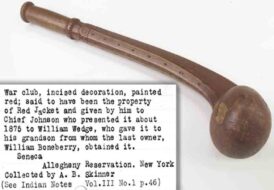

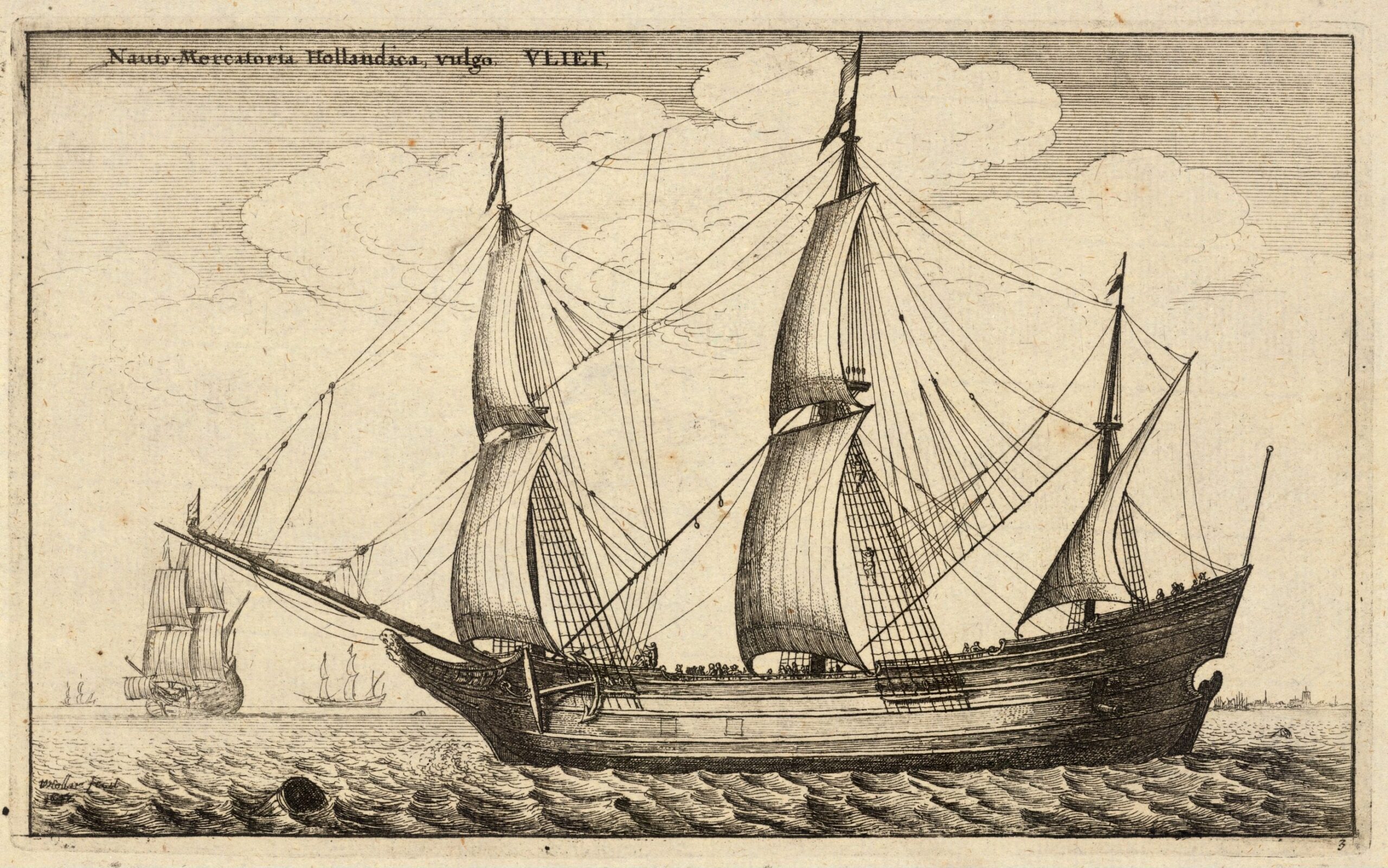

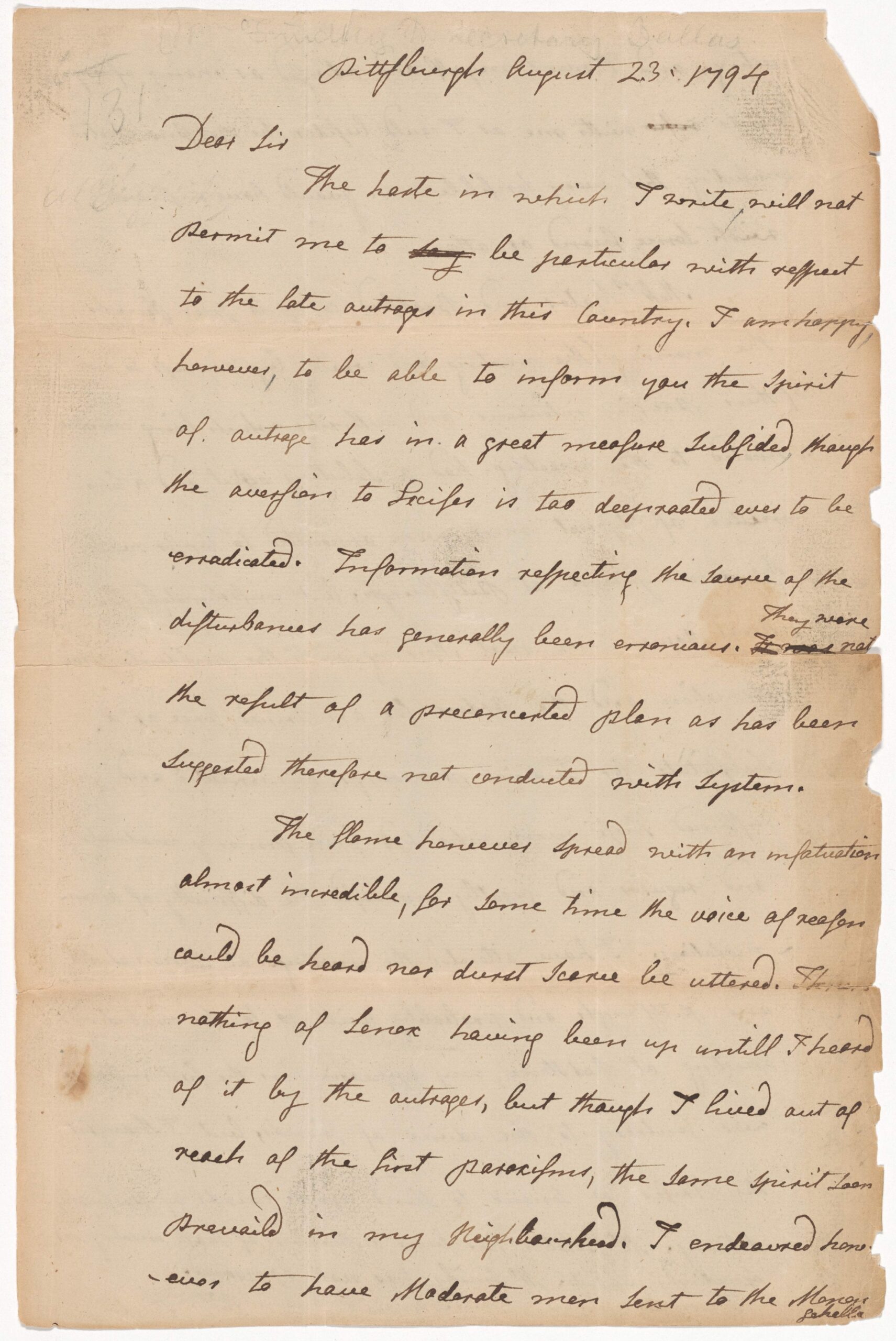

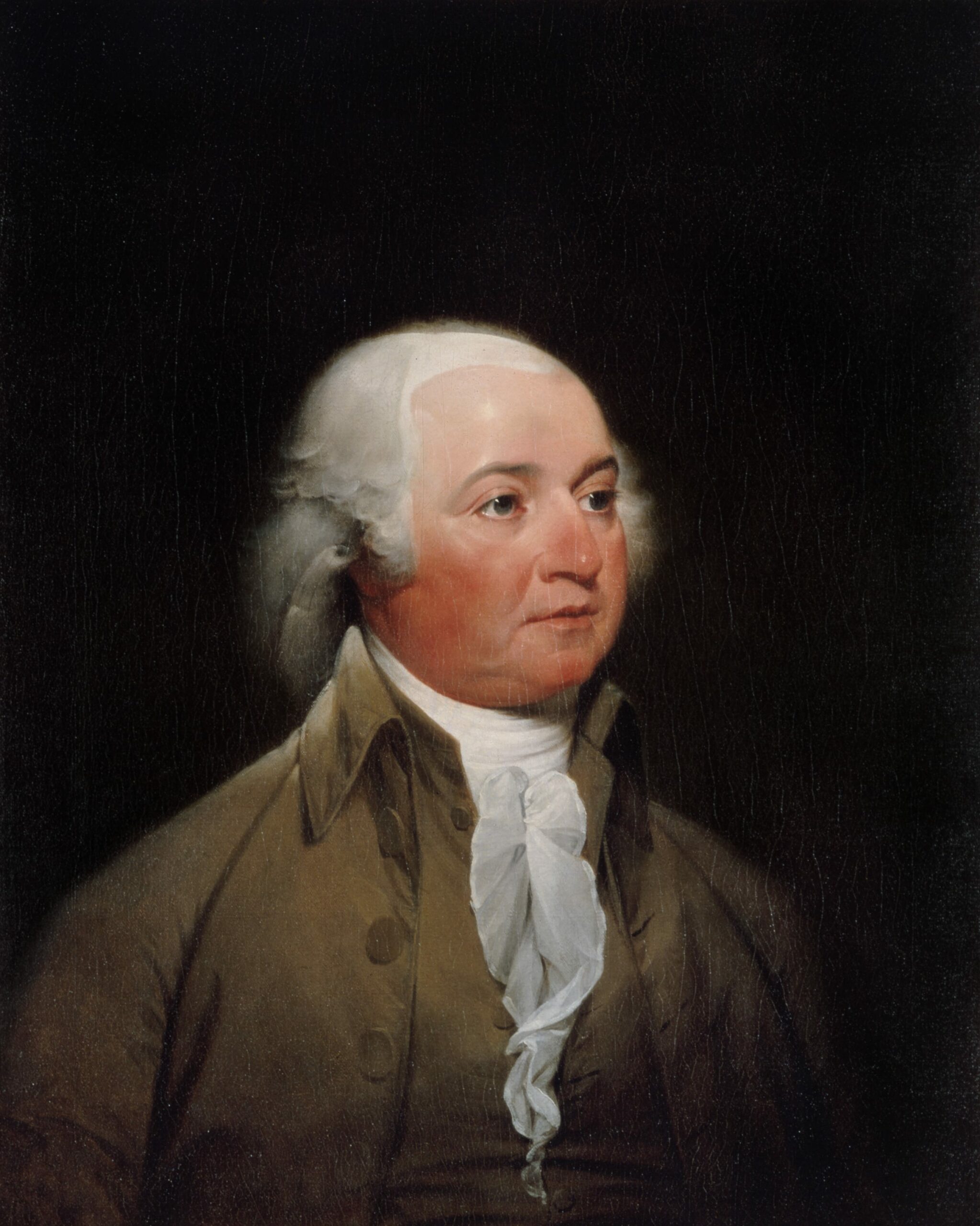

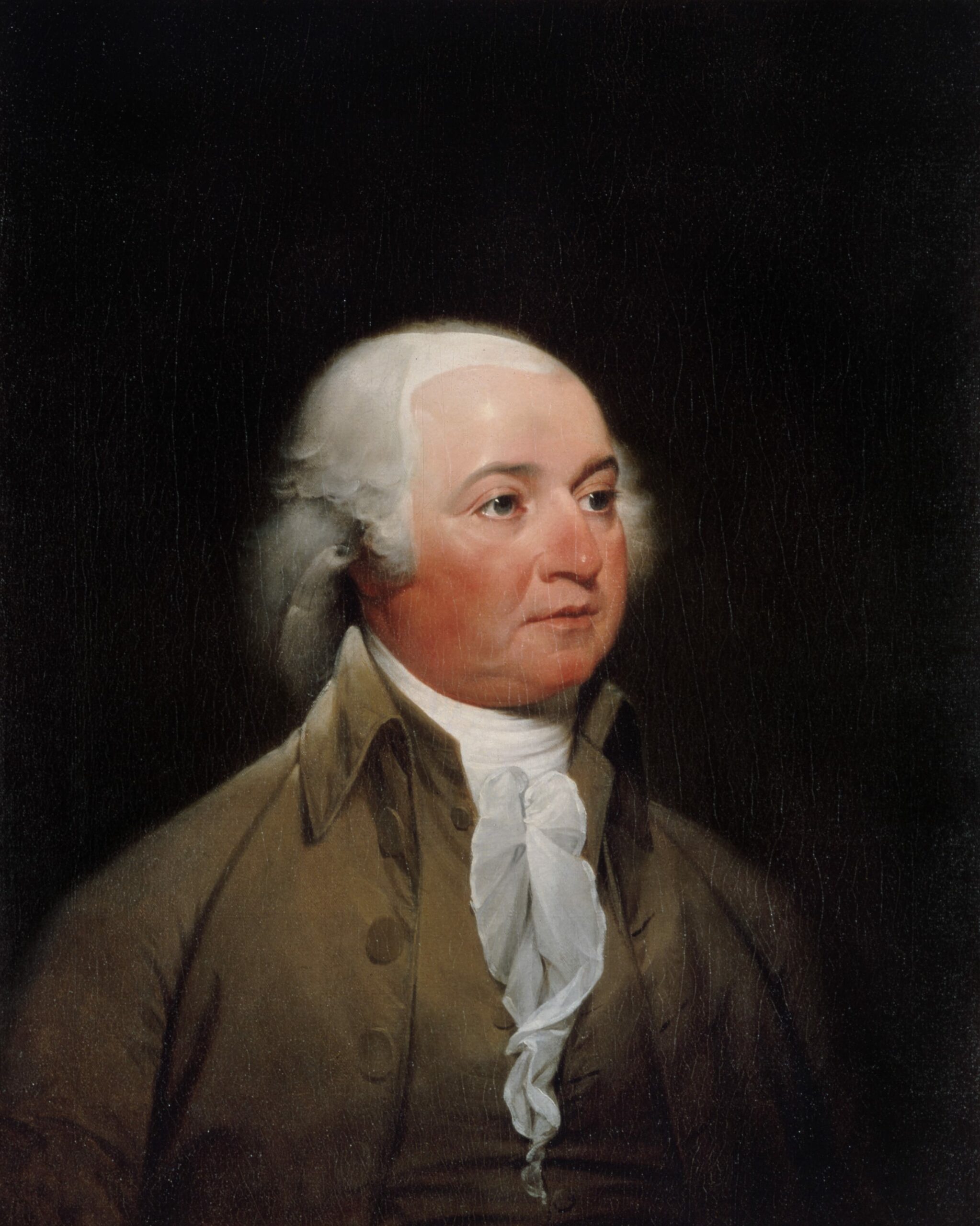

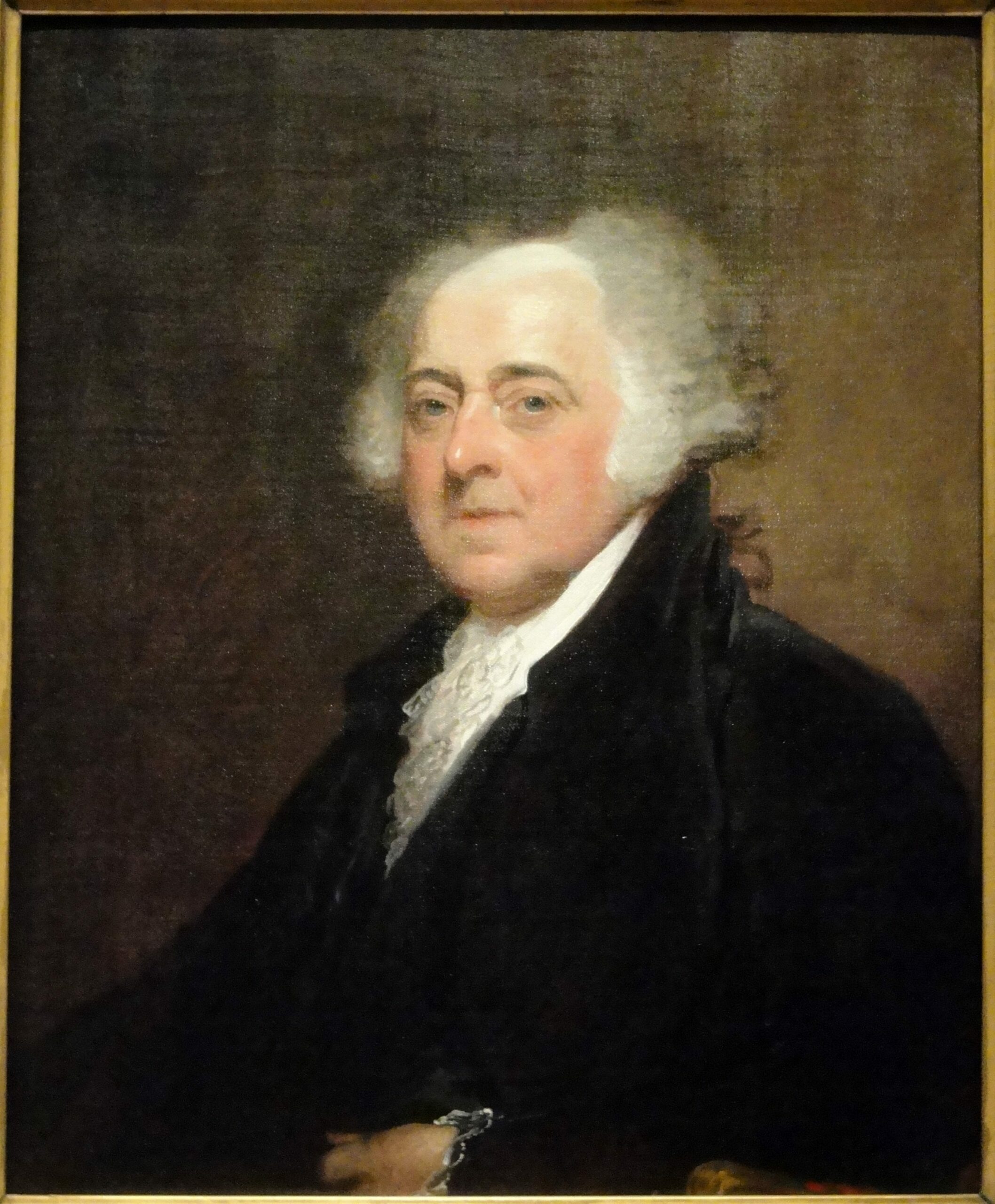

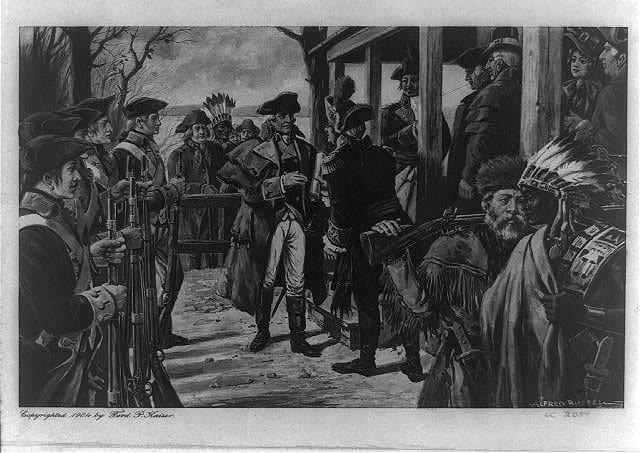

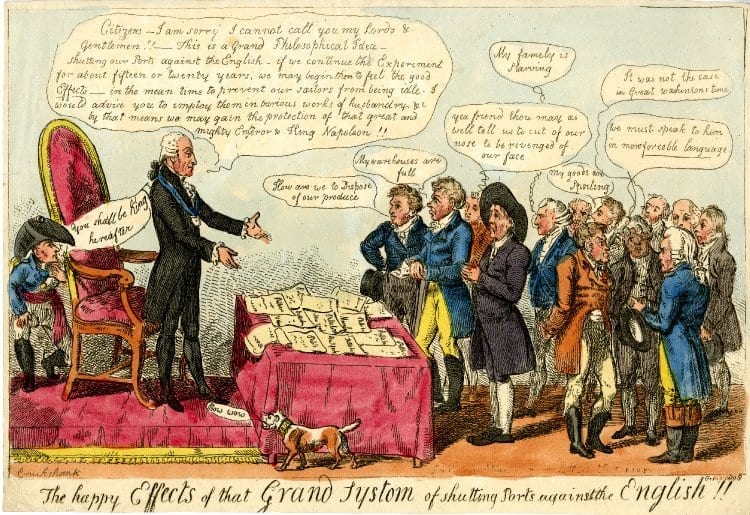

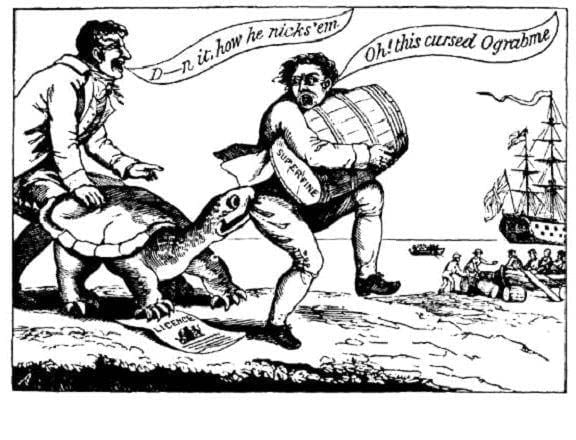

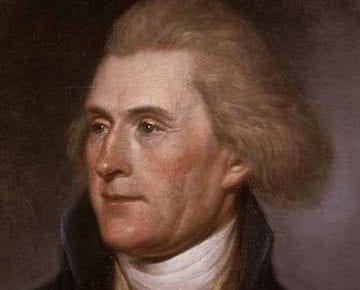

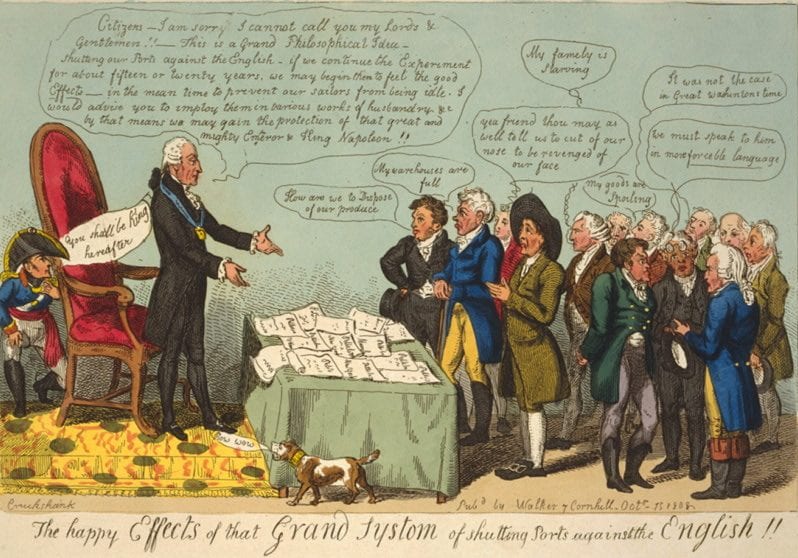

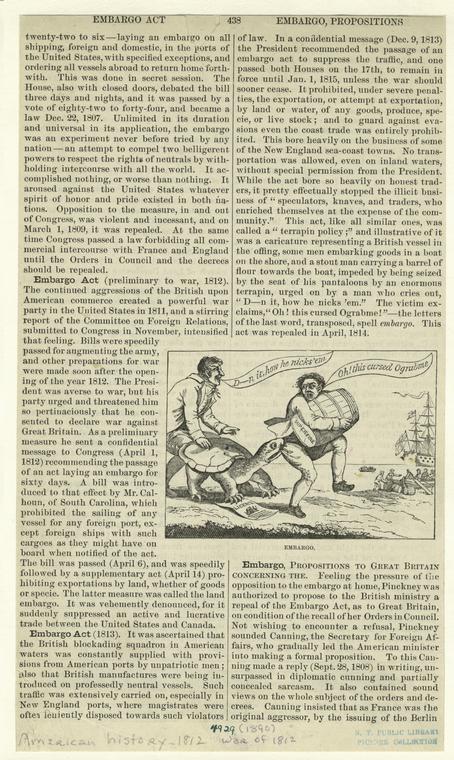

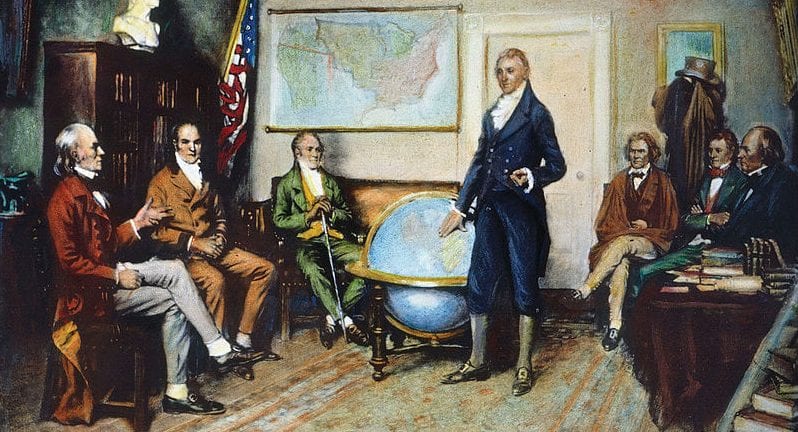

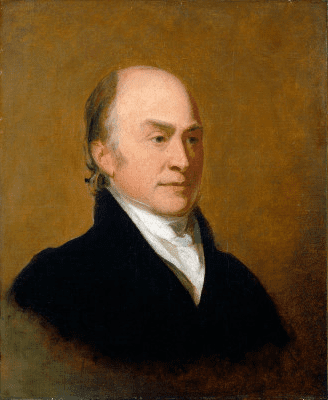

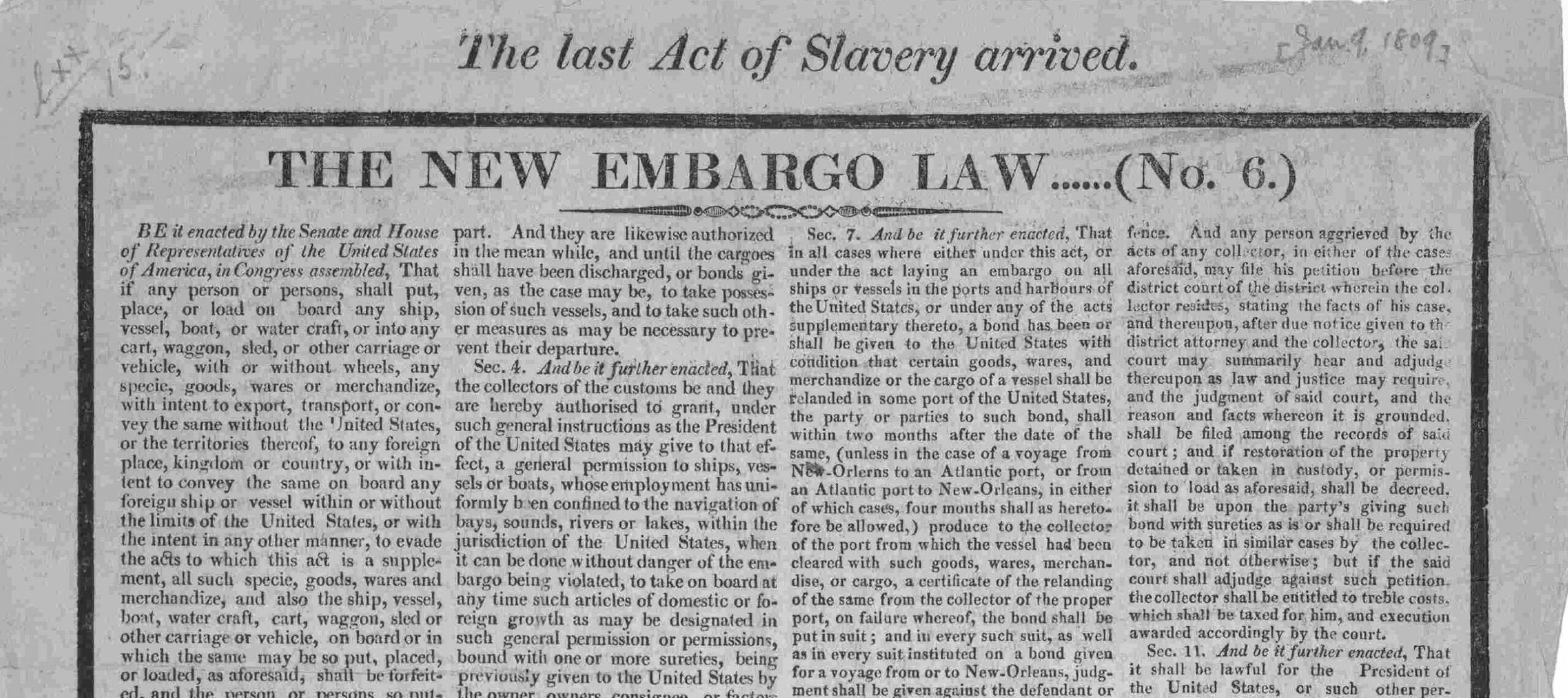

The tumultuous debate over Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation was followed by an equally contentious debate over the ratification of the Jay Treaty between the United States and Great Britain. President Washington dispatched Chief Justice John Jay to London to settle some of the issues left unsettled by the Treaty of Paris in 1783, including the presence of British forts in the northwestern United States, British impressment of American sailors on the high seas, and potential compensation for southern slaveholders whose “property” had fled to the British during the war. Washington was also determined to avoid conflict with the nation’s largest trading partner, but in so doing he enraged the French, who saw the Jay Treaty as a violation of the pact signed with that nation in 1778. At home, the treaty was seen by the Democratic-Republicans as a traitorous agreement between the “Anglomen” within the American government and an empire determined to erode America’s sovereignty and insult its honor.

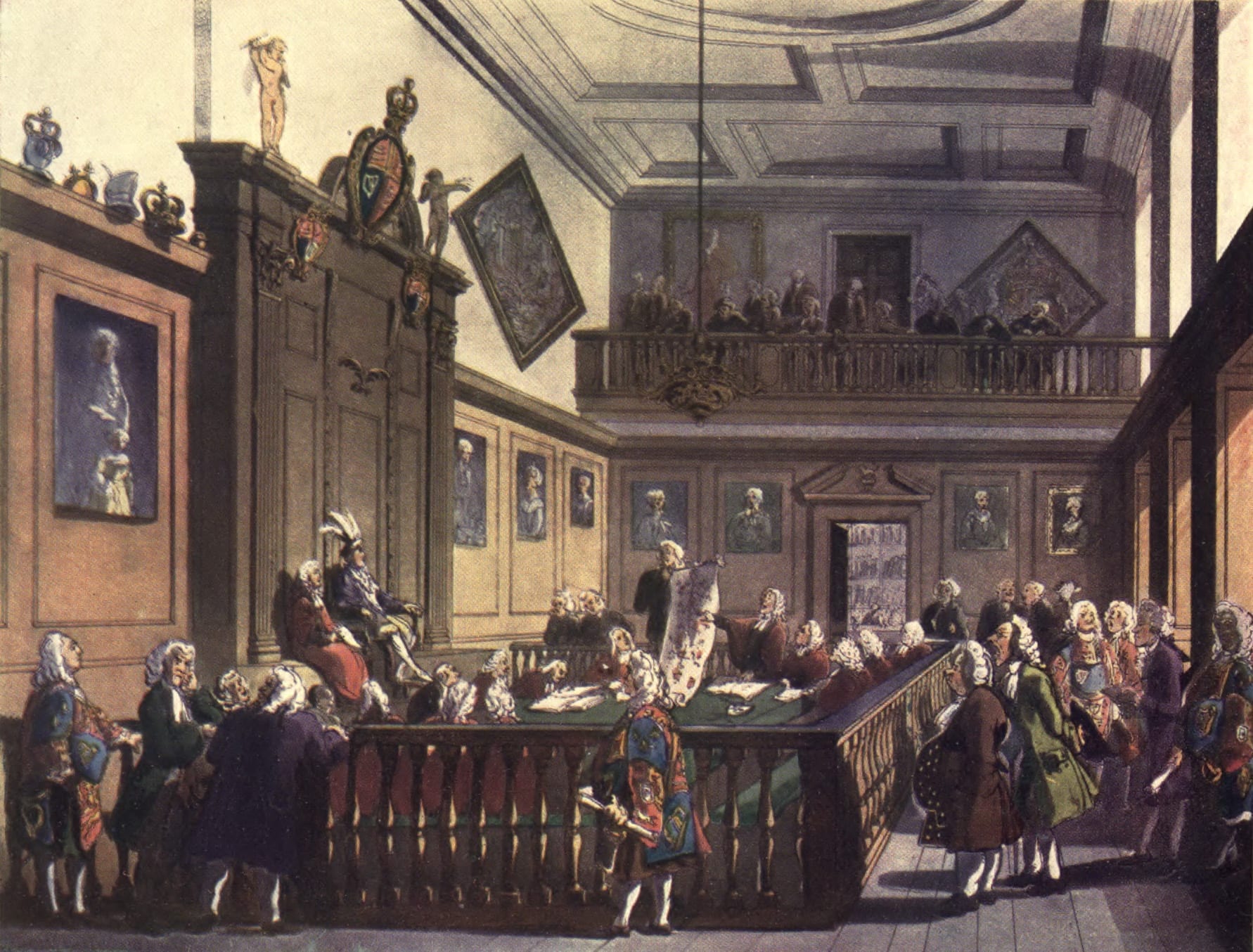

The administration won the battle to ratify the treaty in the U.S. Senate without a vote to spare, twenty to ten (Article II, section 2 requires that two-thirds of the Senate approve a treaty). But so determined was the opposition to block this treaty that the House of Representatives, despite the lack of any constitutional role in the ratification process, decided to investigate to determine if Jay or anyone else had engaged in nefarious practices during the negotiations. The House threatened to withhold funds for implementing the treaty, including money for an arbitration commission designed to settle border disputes with Great Britain, unless the president handed over the documents dealing with the treaty. Washington, in no uncertain terms, denied the request, setting yet another precedent for presidential control over the direction of American foreign policy by invoking what became known as “executive privilege.”

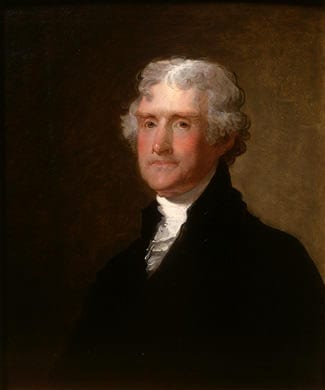

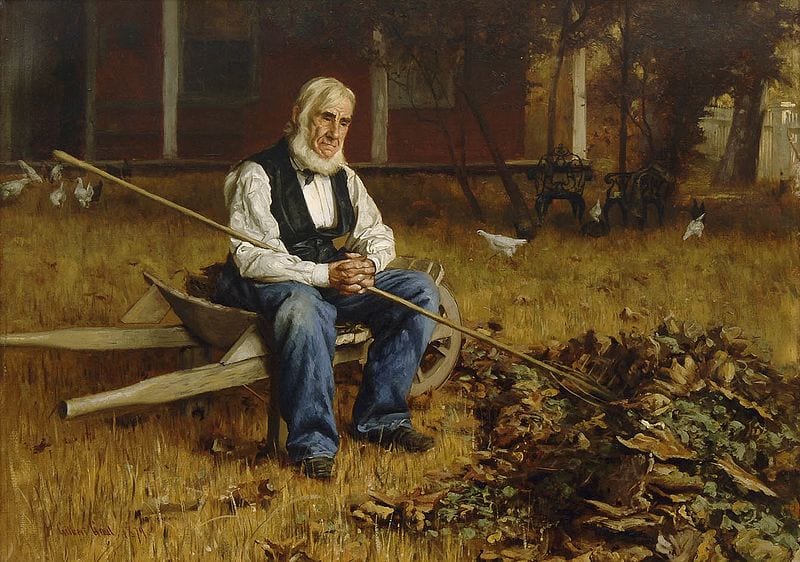

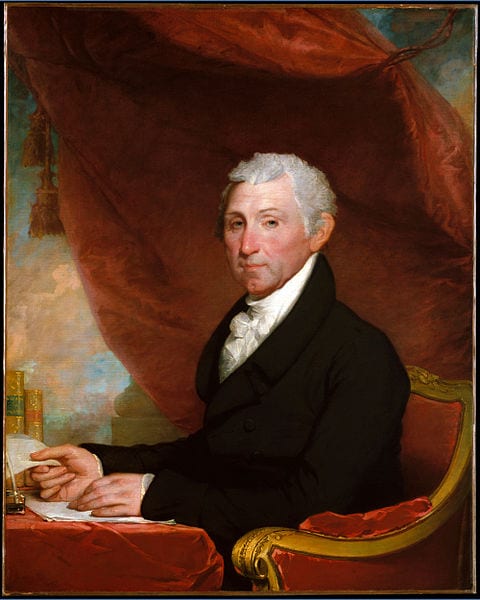

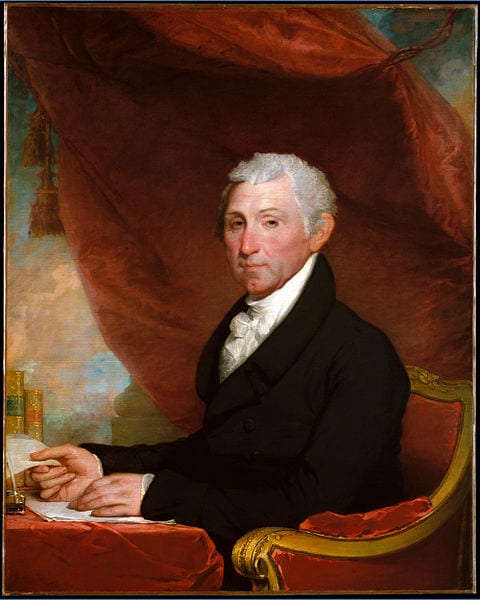

—Stephen F. Knott

Gentlemen of the House of Representatives:

With the utmost attention I have considered your resolution of the 24th instant,1 requesting me to lay before your House, a copy of the instructions to the minister of the United States who negotiated the treaty with the king of Great Britain,2 together with the correspondence and other documents relative to that treaty, excepting such of the said papers as any existing negotiation may render improper to be disclosed.

In deliberating upon this subject, it was impossible for me to lose sight of the principle which some have avowed in its discussion; or to avoid extending my views to the consequences which must flow from the admission of that principle.

I trust that no part of my conduct has ever indicated a disposition to withhold any information which the Constitution has enjoined upon the president as a duty to give, or which could be required of him by either house of Congress as a right; and with truth I affirm that it has been as it will continue to be, while I have the honor to preside in the government, my constant endeavor to harmonize with the other branches thereof; so far as the trust delegated to me by the people of the United States, and my sense of the obligation it imposes to “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution” will permit.3

The nature of foreign negotiations requires caution; and their success must often depend on secrecy: and even when brought to a conclusion, a full disclosure of all the measures, demands, or eventual concessions which may have been proposed or contemplated would be extremely impolitic: for this might have a pernicious influence on future negotiations; or produce immediate inconveniences, perhaps danger and mischief, in relation to other powers. The necessity of such caution and secrecy was one cogent reason for vesting the power of making treaties in the president, with the advice and consent of the Senate, the principle on which that body was formed confining it to a small number of members.

To admit then a right in the House of Representatives to demand, and to have as a matter of course, all the papers respecting a negotiation with a foreign power, would be to establish a dangerous precedent….

As therefore it is perfectly clear to my understanding, that the assent of the House of Representatives is not necessary to the validity of a treaty: as the treaty with Great Britain exhibits in itself all the objects requiring legislative provision; and on these the papers called for can throw no light: and as it is essential to the due administration of the government, that the boundaries fixed by the Constitution between the different departments should be preserved: a just regard to the Constitution and to the duty of my office, under all the circumstances of this case, forbids a compliance with your request.