No related resources

Introduction

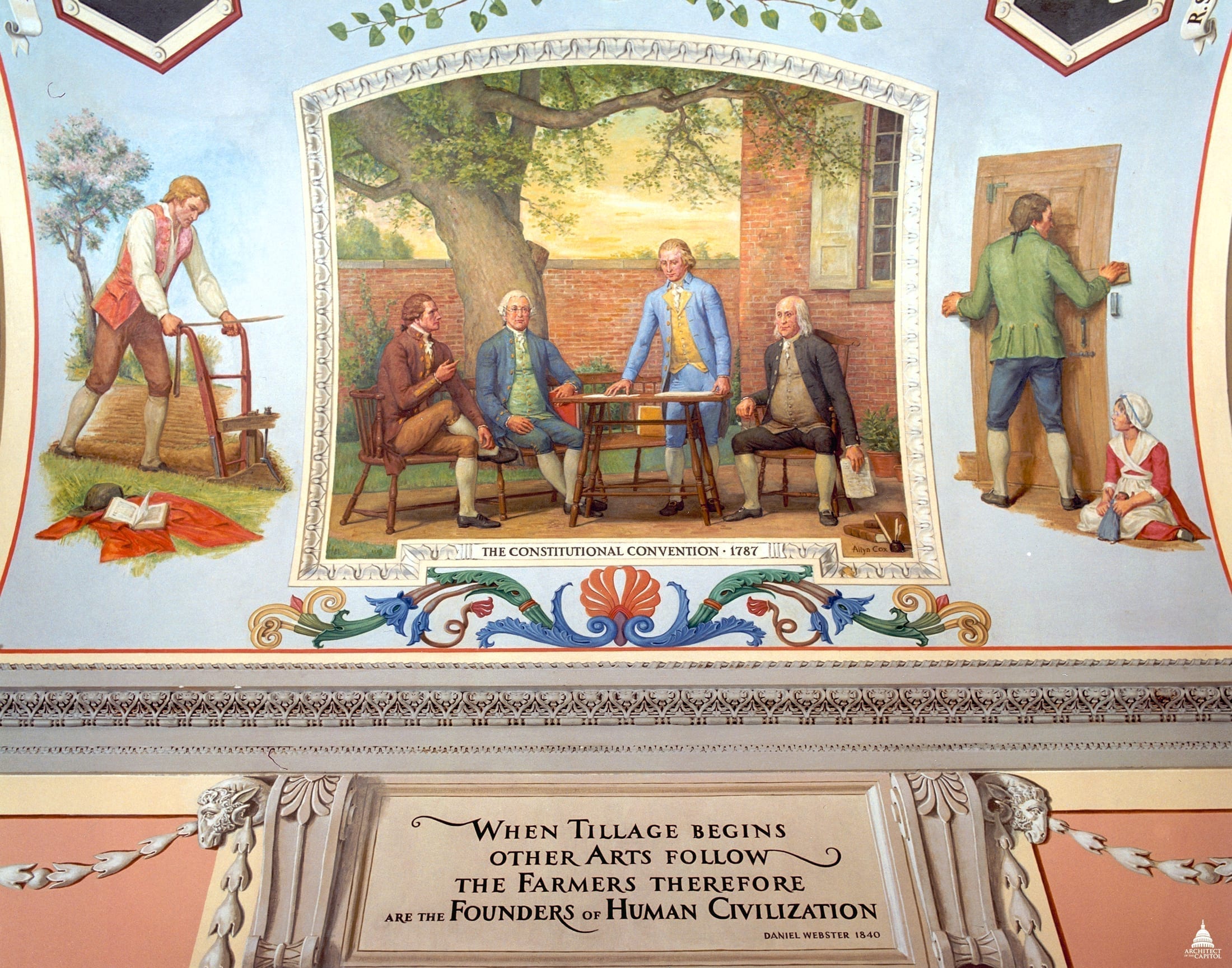

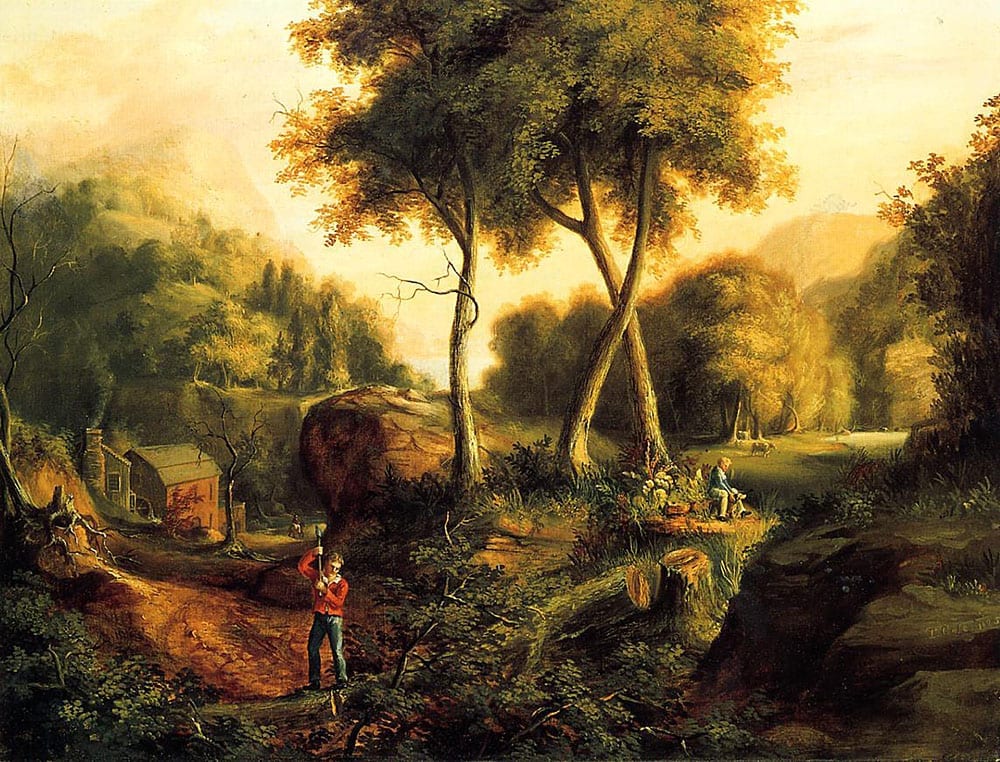

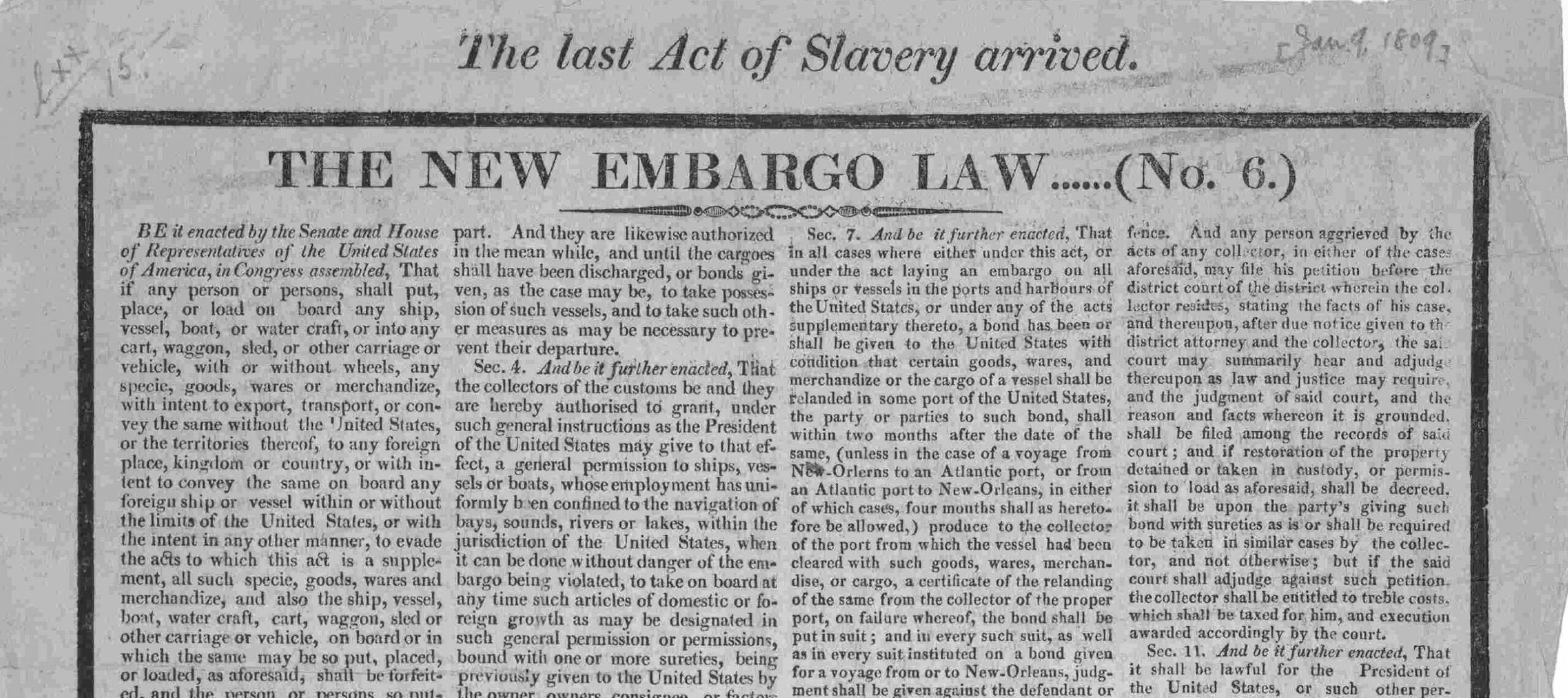

The hope that slavery was on course to extinction, expressed by delegates at the Constitutional Convention (“The Constitutional Convention: The Slave Trade Clause, August, 1787“), came to nothing, smothered by cotton. Once there was a way to efficiently remove seeds from raw cotton (Eli Whitney’s cotton gin or engine, invented in 1793) the way was open to large scale cultivation, driven by the demand from northern American and British cotton mills. Between 1790 and 1800, South Carolina’s cotton exports grew from 10,000 to 6,000,000 pounds. According to those who grew it, cotton required slave labor. The slave population of the United States doubled between 1790 and 1820, to slightly more than 1.5 million. With the end of the slave trade in 1808, most of this increase was from natural population growth.

As the cotton plantation system spread across the south, talk of emancipation receded. National institutions accommodated themselves to the demands of the cotton slave economy. Among the institutions that made accommodations were churches. Baptists and Methodists backed away from confronting slavery in the early nineteenth century, as southern congregations began resisting any condemnation of it. The Presbyterians, at the time perhaps the exemplary denomination in the national Protestant establishment, condemned slavery as unchristian at their General Assembly in 1818, but did not demand action against the institution. They encouraged the colonization of free African Americans, and the religious instruction of those still enslaved. The General Assembly also agreed that if a church member sold a slave who was a church member against his or her will—the action that brought slavery to the attention of the Assembly—then the slave owner should be separated from the church, until he or she repented and repaired as far as possible the damage done.

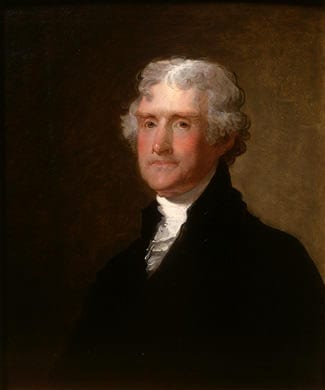

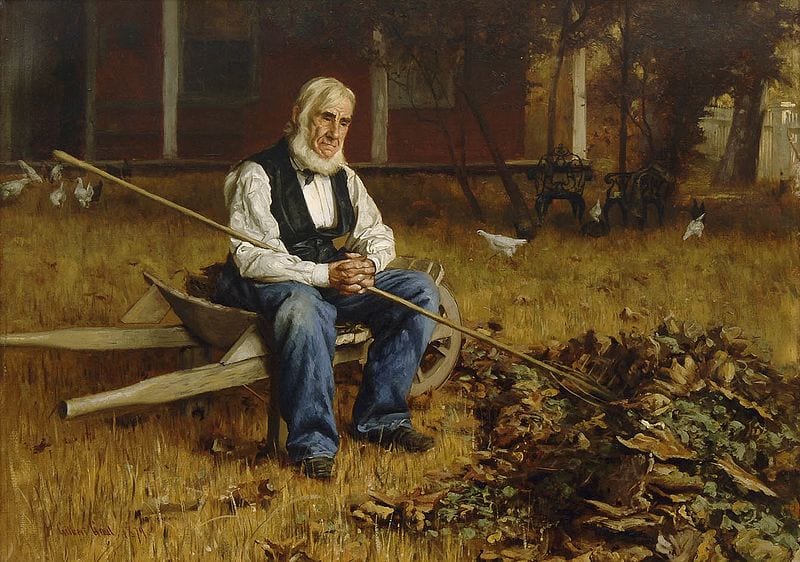

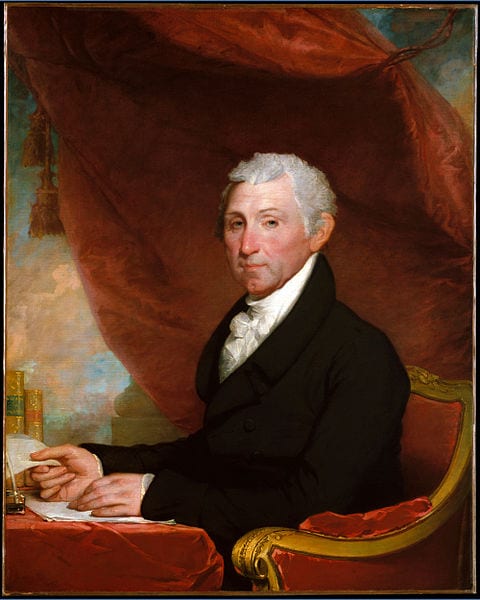

The author of the minutes was Ashbel Green (1762–1848), a Presbyterian minister and President of Princeton University, an established figure in a well-established denomination. In its moral but careful, compromising tone, the minutes reveal the temporizing response of many Americans to the rising slave power.

Source: Minutes of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America from its organization A.D. 1789 to A.D. 1820 inclusive (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1847), 692–694.

The committee to which was referred the resolution on the subject of selling a slave, a member of the Church, and which was directed to prepare a report to be adopted by the Assembly, expressing their opinion in general on the subject of slavery, reported, and their report being read, was unanimously adopted, and referred to the same committee for publication. It is as follows, viz:

The General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church, having taken into consideration the subject of slavery, think proper to make known their sentiments upon it to the churches and people under their care.

We consider the voluntary enslaving of one part of the human race by another, as a gross violation of the most precious and sacred rights of human nature; as utterly inconsistent with the law of God, which requires us to love our neighbor as ourselves, and as totally irreconcilable with the spirit and principles of the gospel of Christ, which enjoin that “all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them.”[1] Slavery creates a paradox in the moral system; it exhibits them as dependent on the will of others, whether they shall receive religious instruction; whether they shall know and worship the true God; whether they shall enjoy the ordinances of the gospel; whether they shall perform the duties and cherish the endearments of husbands and wives, parents and children, neighbors and friends; whether they shall preserve their chastity and purity, or regard the dictates of justice and humanity. Such are some of the consequences of slavery—consequences not imaginary, but which connect themselves with its very existence. The evils to which the slave is always exposed often take place in fact, and in their very worst degree and form; and where all of them do not take place, as we rejoice to say in many instances, through the influence of the principles of humanity and religion on the mind of masters, they do not—still the slave is deprived of his natural right, degraded as a human being, and exposed to the danger of passing into the hands of a master who may inflict upon him all the hardships and injuries which inhumanity and avarice may suggest.

From this view of the consequences resulting from the practice into which Christian people have most inconsistently fallen, of enslaving a portion of their brethren of mankind—for “God hath made of one blood all nations of men to dwell on the face of the earth”[2] —it is manifestly the duty of all Christians who enjoy the light of the present day, when the inconsistency of slavery, both with the dictates of humanity and religion, has been demonstrated, and is generally seen and acknowledged, to use their honest, earnest, and unwearied endeavors, to correct the errors of former times, and as speedily as possible to efface this blot on our holy religion, and to obtain the complete abolition of slavery throughout Christendom, and if possible throughout the world.

We rejoice that the Church to which we belong commenced as early as any other in this country, the good work of endeavoring to put an end to slavery, and that in the same work many of its members have ever since been, and now are, among the most active, vigorous, and efficient laborers. We do, indeed, tenderly sympathize with those portions of our church and our country where the evil of slavery has been entailed upon them; where a great, and the most virtuous part of the community abhor slavery, and wish its extermination as sincerely as any others—but where the number of slaves, their ignorance, and their vicious habits generally, render an immediate and universal emancipation inconsistent alike with the safety and happiness of the master and the slave. With those who are thus circumstanced, we repeat that we tenderly sympathize. At the same time, we earnestly exhort them to continue, and if possible to increase their exertions to effect a total abolition of slavery. We exhort them to suffer no greater delay to take place in this most interesting concern, than a regard to the public welfare truly and indispensably demands.

As our country has inflicted a most grievous injury on the unhappy Africans, by bringing them into slavery, we cannot indeed urge that we should add a second injury to the first, by emancipating them in such manner as that they will be likely to destroy themselves or others. But we do think, that our country ought to be governed in this matter by no other consideration than an honest and impartial regard to the happiness of the injured party, uninfluenced by the expense or inconvenience which such a regard may involve. We, therefore, warn all who belong to our denomination of Christians against unduly extending this plea of necessity; against making it a cover for the love and practice of slavery, or a pretense for not using efforts that are lawful and practicable, to extinguish this evil.

And we, at the same time exhort others to forbear harsh censures, and uncharitable reflections on their brethren, who unhappily live among slaves, whom they cannot immediately set free; but who, at the same time, are really using all their influence, and all their endeavors, to bring them into a state of freedom, as soon as a door for it can be safely opened.

Having thus expressed our views of slavery, and of the duty indispensably incumbent on all Christians to labor for its complete extinction, we proceed to recommend, and we do it with all the earnestness and solemnity which this momentous subject demands, a particular attention to the following points.

We recommend to all our people to patronize and encourage the society lately formed, for colonizing in Africa, the land of their ancestors, the free people of color in our country.[3] We hope that much good may result from the plans and efforts of this society. And while we exceedingly rejoice to have witnessed its origin and organization among the holders of slaves, as giving an unequivocal pledge of their desires to deliver themselves and their country from the calamity of slavery; we hope that those portions of the American union, whose inhabitants are, by a gracious providence, more favorably circumstanced, will cordially, and liberally, and earnestly cooperate with their brethren, in bringing about the great end contemplated.

We recommend to all the members of our religious denomination, not only to permit, but to facilitate and encourage the instruction of their slaves, in the principles and duties of the Christian religion; by granting them liberty to attend on the preaching of the gospel, when they have opportunity; by favoring the instruction of them in the Sabbath-school, wherever those schools can be formed; and by giving them all other proper advantages for acquiring the knowledge of their duty both to God and to man. We are perfectly satisfied, that it is incumbent on all Christians to communicate religious instruction to those who are under their authority, so that the doing of this in the case before us, so far from operating, as some have apprehended that it might, as an incitement to insubordination and insurrection, would, on the contrary, operate as the most powerful means for the prevention of those evils.

We enjoin it on all church sessions and Presbyteries,[4] under the care of this Assembly, to discountenance, and as far as possible to prevent all cruelty of whatever kind in the treatment of slaves; especially the cruelty of separating husband and wife, parents and children, and that which consists in selling slaves to those who will either themselves deprive these unhappy people of the blessings of the gospel, or who will transport them to places where the gospel is not proclaimed, or where it is forbidden to slaves to attend upon its institutions. And if it shall ever happen that a Christian professor[5] in our communion shall sell a slave who is also in communion and good standing with our Church, contrary to his or her will, and inclination, it ought immediately to claim the particular attention to the proper church judicature; and unless there be such peculiar circumstances attending the case as can but seldom happen, it ought to be followed, without delay, by a suspension of the offender from all the privileges of the church, till he repent, and make all the reparation in his power to the injured party.

Resolved, That fifteen hundred copies of this report be printed or published in the newspapers.

- 1. Matthew 7:12.

- 2. Acts 17:26.

- 3. The Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America or the African Colonization Society formed in 1816. In 1810, there were approximately 186,446 free African Americans in the United States, about 13% of the total African population.

- 4. Administrative bodies in the Presbyterian church. Each church is governed by an elected session; presbyteries handle administrative concerns for all churches within a district.

- 5. Someone who has affirmed his Christian faith.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.