Introduction

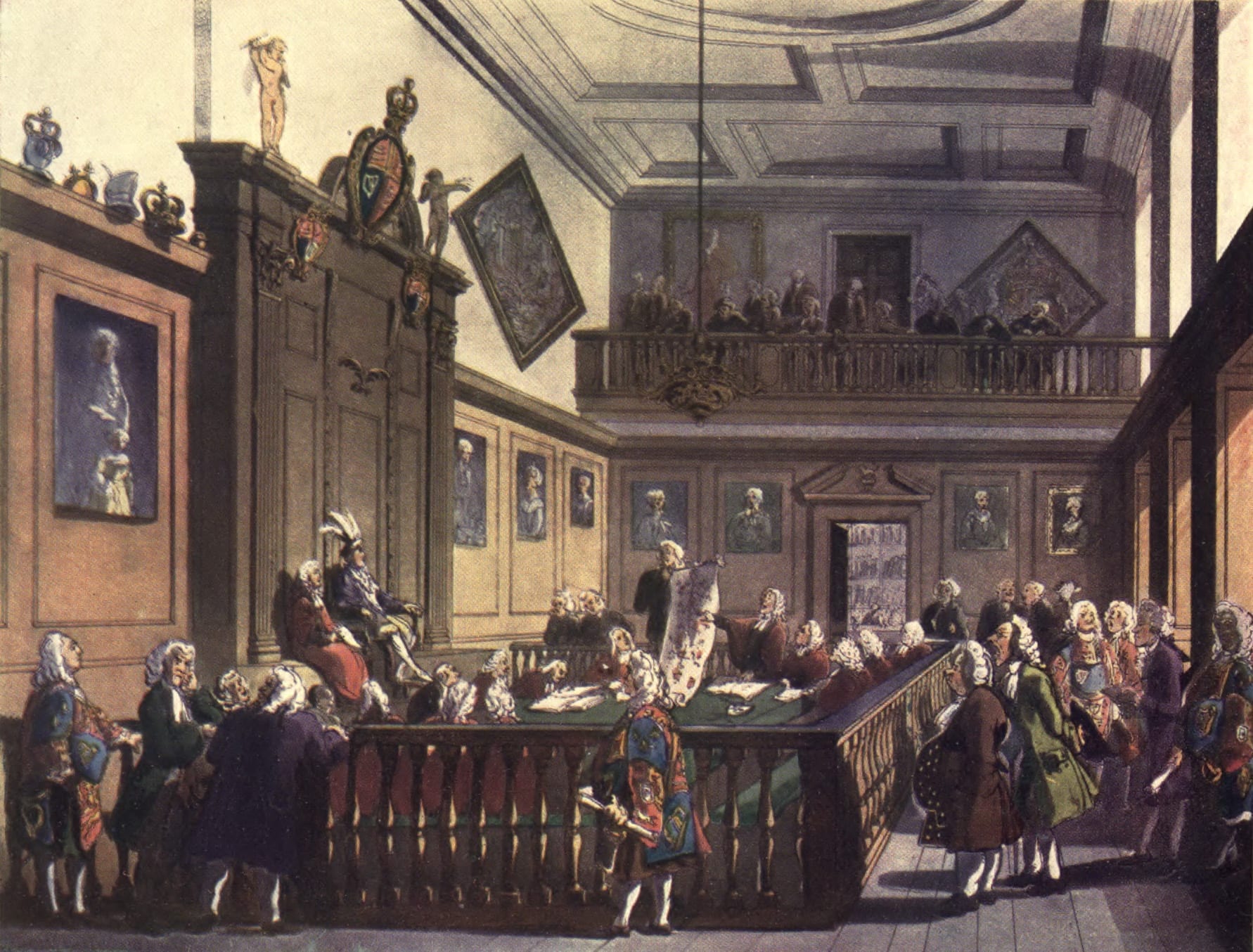

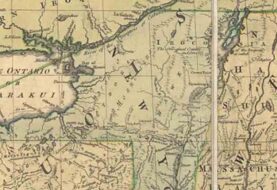

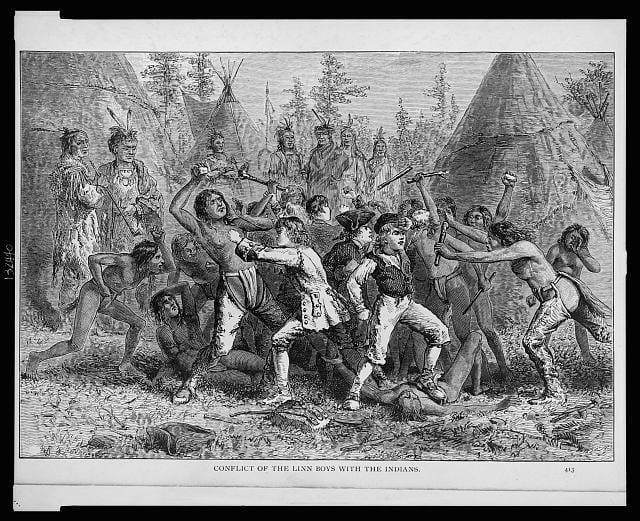

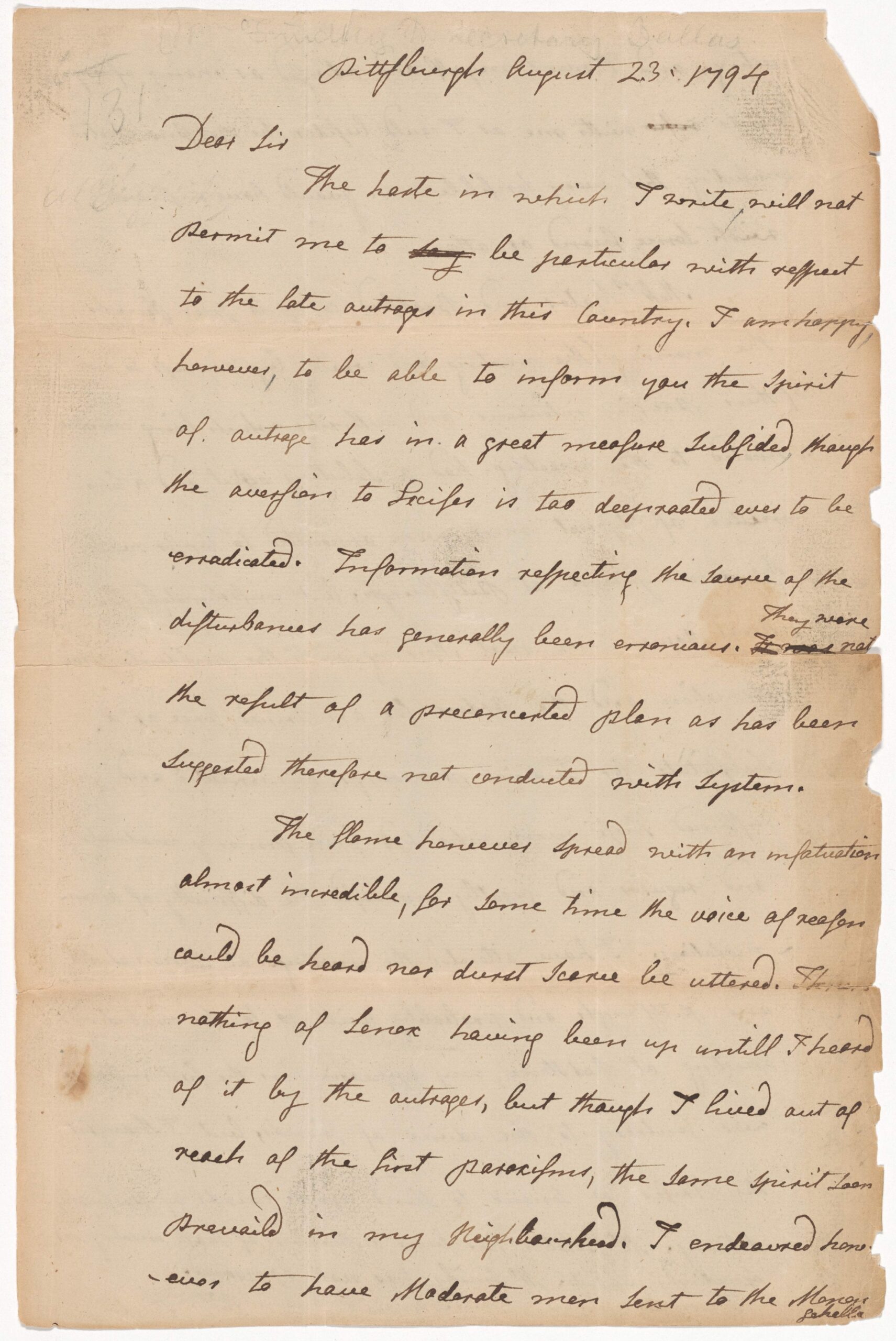

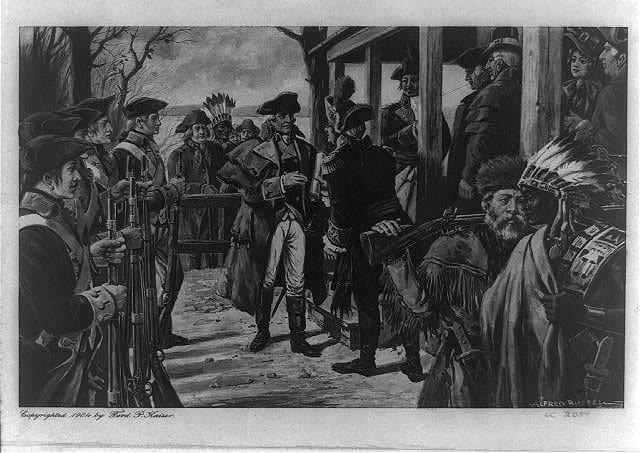

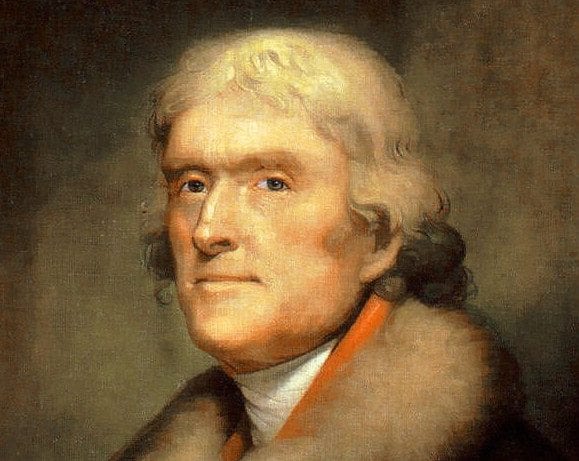

One of the major challenges confronting the Washington administration was the new republic’s relations with the Native American tribes both within and beyond its borders. In 1789, Washington’s government sought to sign a treaty with the Creek Indians and created a commission to negotiate with the tribe’s leaders. Seeking to abide by the “advice and consent” provisions of the Constitution (Article II, section 2) regarding the Senate’s treaty powers, Washington appeared in person before the Senate on August 22, and then again two days later, hoping to receive feedback on the proposed treaty. In this message, Washington condemned the “violations” committed by “disorderly white people” on the frontier, noted the ever-present threat of European machinations with various tribes on the nation’s borders, and also noted the importance of selecting commissioners who were not captive to local prejudices.

The meeting quickly deteriorated after Washington addressed the Senate. Some senators seemed intimidated by Washington, while others seemed unable to focus on the matter at hand. Senator William Maclay of Pennsylvania described Washington’s interactions with the Senate as cold and brusque. “The President was introduced … he rose and told us bluntly that he had called on us for our advice and consent to some propositions respecting the treaties to be held with the southern Indians. … Carriages were driving past and such a noise I could tell it was something about Indians, but was not master of one sentence of it. … Mr. Morris rose said the noise of carriages had been so great that he really could not say that he had heard the body of the paper which was read and prayed it might be read again.” Maclay suggested the matter be turned over to a committee, a proposal that displeased the president. According to Maclay, “Peevishness itself I think could not have taken offense at anything I said, as I sat down the president of the U.S. started up in a violent fret. ‘This defeats every purpose of my coming here,’ were the first words that he said … a pause for some time ensued. We waited for him to withdraw, he did so with a discontented air. Had it been any other, than the man who I wish to regard as the first character in the world, I would have said with ‘sullen dignity.’”

Frustrated by the Senate’s halting and disjointed response to his request for advice, Washington vowed never again to involve the Senate in treaty negotiations, setting a precedent for the president to take the lead in directing American foreign policy and relegating the Senate to a reactive, somewhat passive role.

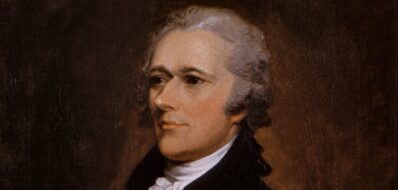

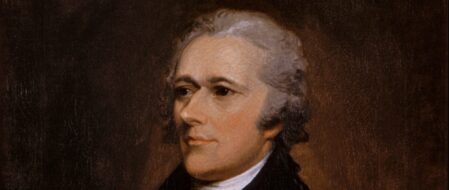

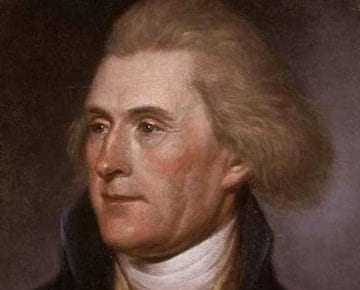

—Stephen F. Knott

George Washington, George Washington Papers, series 2, Letterbooks 1754–1799: Letterbook 25, April 6, 1789–March 4, 1791, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/mgw2.025/.

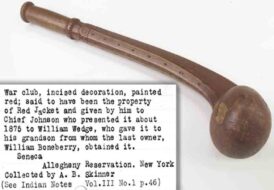

To conciliate the powerful tribes of Indians in the southern district, amounting probably to fourteen thousand fighting men, and to attach them firmly to the United States, may be regarded as highly worthy of the serious attention of government. The measure includes, not only peace and security to the whole southern frontier, but is calculated to form a barrier against the colonies of a European power, which, in the mutations of policy, may one day become the enemy of the United States. The fate of the southern states therefore, or the neighboring colonies, may principally depend on the present measures of the Union toward the southern Indians. By the papers which have been laid before the Senate it will appear that in the latter end of the year 1785 and the beginning of 1786, treaties were formed by the United States with the Cherokees,1 the Chickasaws2 and Choctaws.3 The report of the commissioners will show the reasons why a treaty was not formed at the same time with the Creeks.4

It will also appear by the papers that the states of North Carolina and Georgia protested against said treaties, as infringing their legislative rights and being contrary to the confederation. It will further appear by the said papers, that the treaty with the Cherokees has been entirely violated by the disorderly white people on the frontiers of North Carolina….

The commissioners may be instructed to transmit messages to the said tribes containing assurances of the continuance of the friendship of the United States….

… By the report of the commissioners who were appointed under certain acts of the late Congress, by South Carolina and Georgia, it appears that they have agreed to meet the Creeks on the 15th of September ensuing. As it is with great difficulty the Indians are collected together at certain seasons of the year, it is important that the above occasion should be embraced, if possible, on the part of the present government, to form a treaty with the Creeks. As the proposed treaty is of great importance to the future tranquility of the state of Georgia, as well as of the United States, it has been thought proper that it should be conducted on the part of the general government, by commissioners whose local situations may free them from the imputation of prejudice on this subject….