Introduction

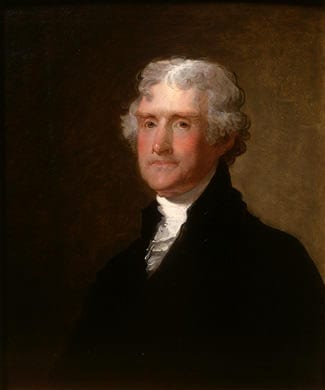

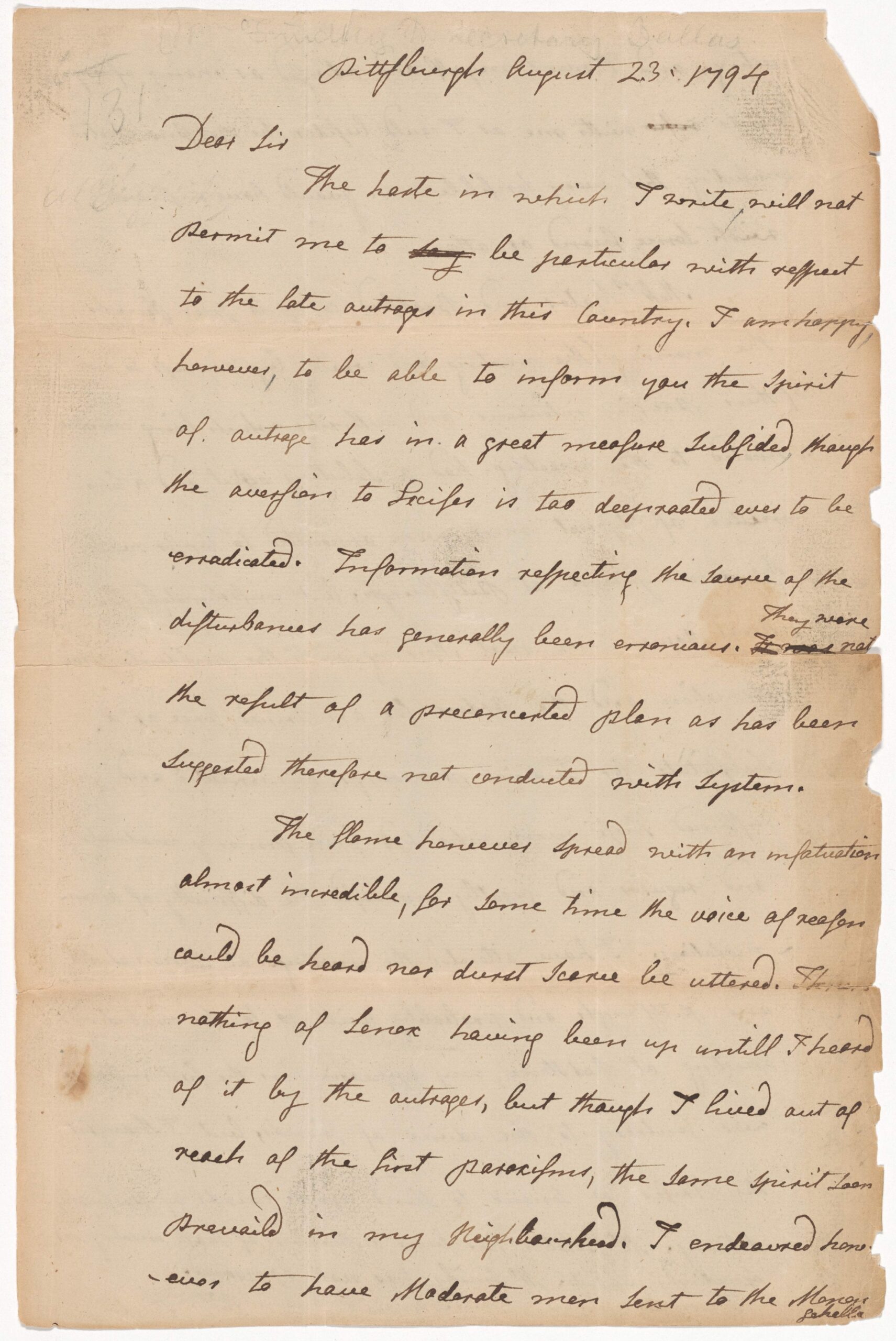

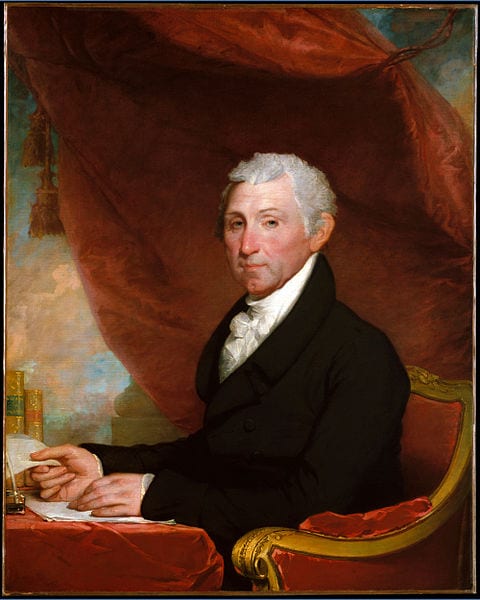

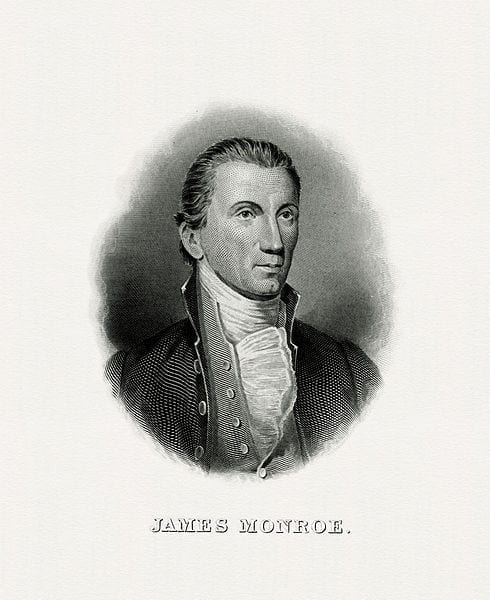

Echoing the sentiment of the Northwest Ordinance, President George Washington hoped that principles of good faith would guide relations with Native Americans who inhabited land that had become part of the United States at the conclusion of the Revolutionary War. For example, in 1789 he instructed commissioners setting off to negotiate a treaty with the southern Indians that however circumstances might force them to modify his instructions, they should “remember that the Government of the United States are determined that their administration of Indian affairs shall be directed entirely by the great principles of Justice and humanity.” Secretary Knox’s report on Indian affairs illustrates the problems that confounded Washington’s hopes.

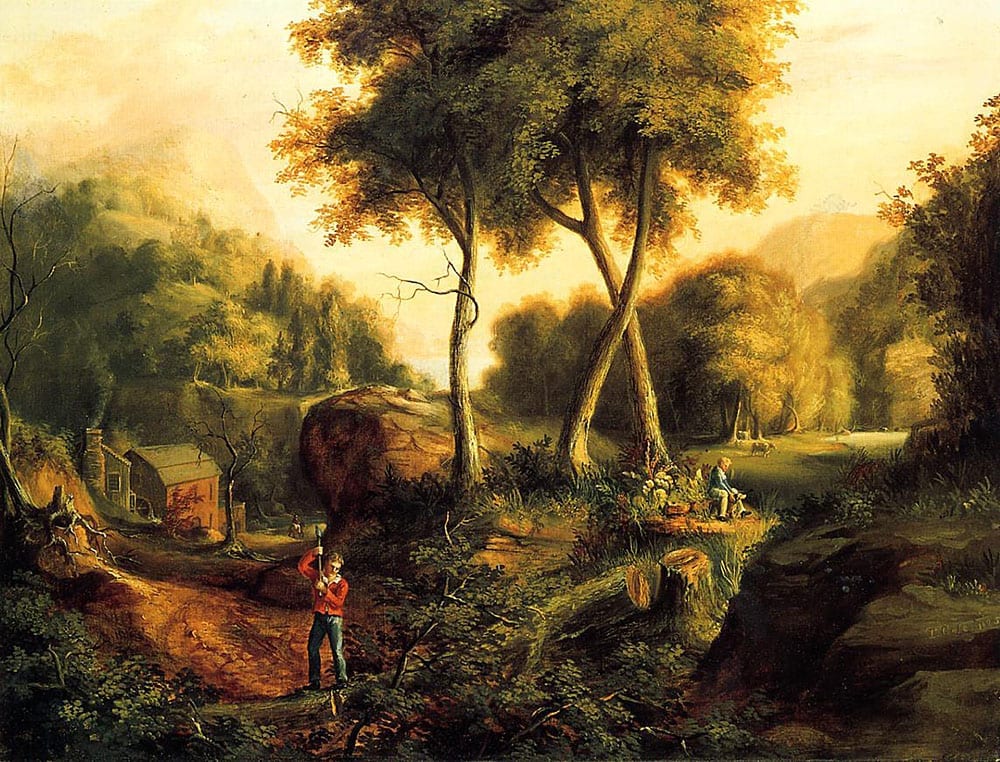

The principal problem was the relentless westward movement of settlers onto Indian land. Knox acknowledged that this occurred through force and fraud. The Indians responded to protect their land. The result was continual conflict and sometimes open warfare between settlers and Indians that was not in the interests of the United States. This was particularly so since it created opportunities for European powers to meddle in the affairs of the young republic. Knox proposed several steps to mitigate the conflict western settlement created. An implicit problem in his proposals and approach was his misconceptions about the Indians’ way of life (for example, that a police function might exist among the Indians as it did among the Americans) and a too hopeful view that Indians would be attracted to Americans’ “civilized” lifestyle.

Knox, like Washington, hoped for an “honorable tranquility” on the frontiers. Neither his policy nor any future American Indian policy achieved this. Instead, what Knox hoped to avoid—the further destruction of the Native Americans—came to pass*. Already in 1794, Knox compared—unfavorably—the effect of American expansion with the results of Spain’s conquest of Mexico and Peru. With the exception of his concern for foreign meddling, which diminished over time, Knox’s report foreshadows the hopes and attitudes, as well as many of the responses and problems, of future U. S. policy toward Native Americans.

*See Jackson’s Second Annual Message, Indian Removal Act, Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, First Annual Message of Chester A. Arthur, and Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Meeting of the Lake Mohonk Conference.

Source: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-17-02-0223-0002.

The secretary of war respectfully submits to the president of the United States the following observations respecting the preservation of the peace with the Indian tribes with whom the United States have formed treaties.

To retrace the conduct of the government of the United States toward the Indian tribes since the adoption of the present constitution, cannot fail to afford satisfaction to every philosophic and humane mind.

A constant solicitude appears to have existed in the executive and Congress not only to form treaties of peace with the Indians upon principles of Justice, but to impart to them all the blessings of civilized life of which their condition is susceptible.

That a perseverance in such principles and conduct will reflect permanent honor upon the national character cannot be doubted—at the same time it must be acknowledged that the execution of the good intentions of the public is frequently embarrassed with perplexing considerations.

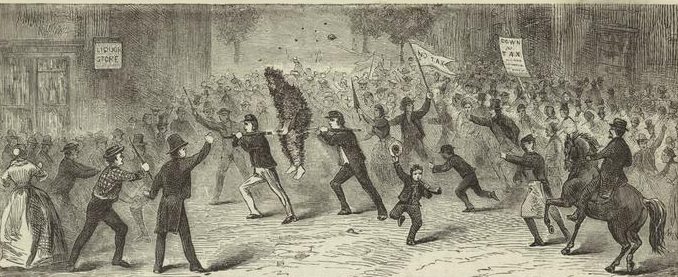

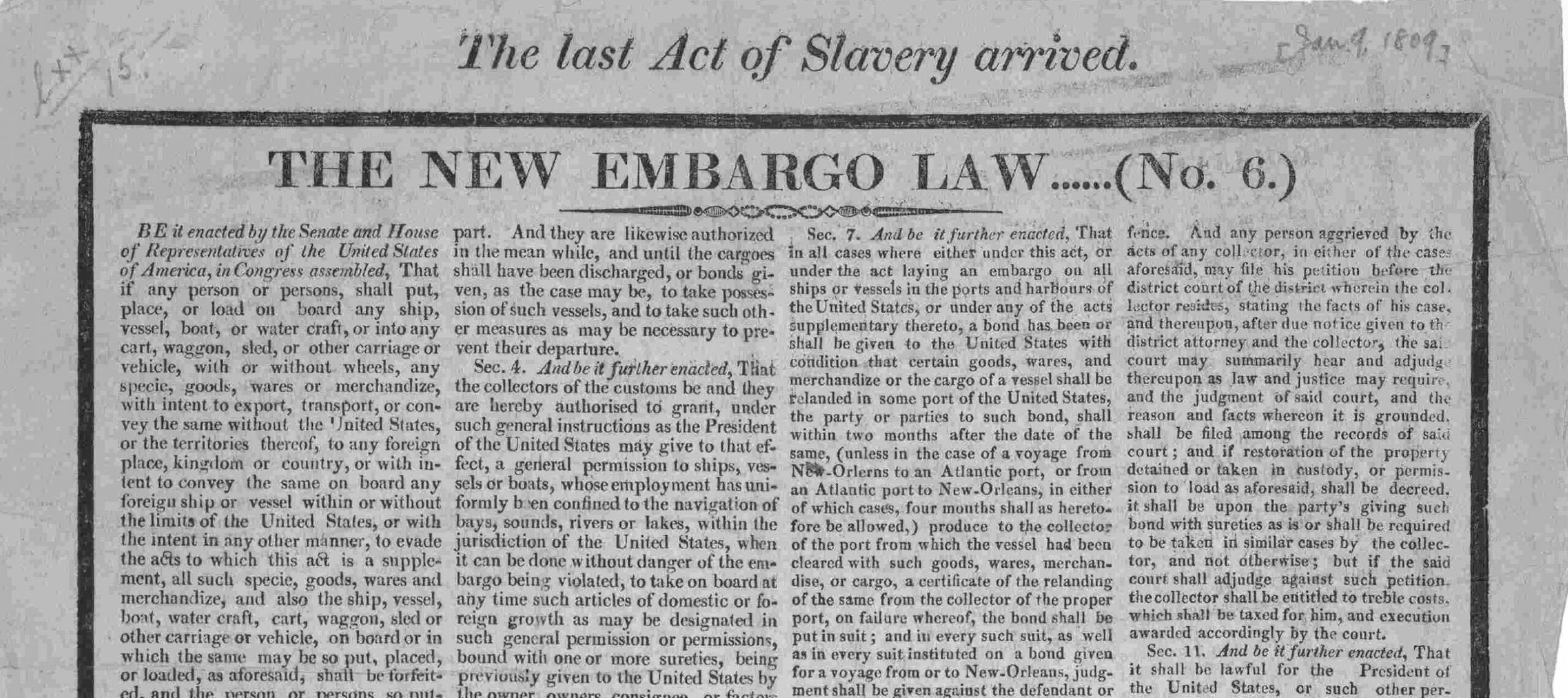

The desires of too many frontier white people to seize by force or fraud upon the neighboring Indian lands has been and still continues to be an unceasing cause of jealousy and hatred on the part of the Indians; and it would appear upon a calm investigation that until the Indians can be quieted upon this point and rely with confidence upon the protection of their lands by the United States no well-grounded hope of tranquility can be entertained.

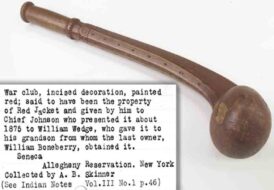

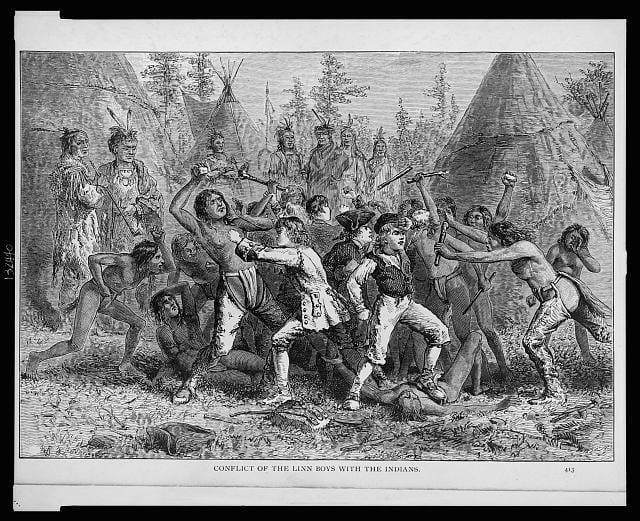

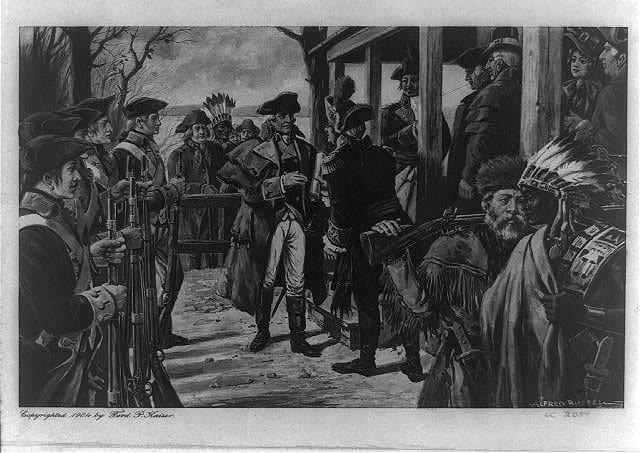

The encroachment of the white people is incessantly watched, and in unguarded moments, they are murdered by the Indians. Revenge is sought and the innocent frontier people are too frequently involved as victims in the cruel contest. This appears to be a principal cause of Indian wars. That there are exceptions will not be denied. The passion of a young savage for war and fame is too mighty to be restrained by the feeble advice of the old men. An adequate police[1] seems to be wanting either to prevent or punish the depredations of the unruly. It would afford a conscious pleasure could the assertion be made on our parts that we have considered the murder of Indians the same as the murders of whites and have punished them accordingly. This however is not the case. The irritated passions on account of savage cruelty are generally too keen in the places where trials are had, to convict and punish for the killing of an Indian. It is considered as unnecessary to cite instances although multitudes might be adduced in almost every part of the country from its first settlement to the present time.

If this view of the inability of both parties to keep the peace be correct, it would seem to follow as a just consequence that an adequate remedy ought to be provided for an evil of such magnitude.

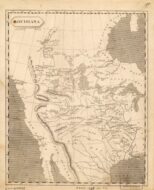

It is certainly an evil to be involved in hostilities with tribes of savages amounting to two or three thousand as is the case north west of the Ohio. But this evil would be greatly increased were a general Indian war to prevail south of the Ohio, the Indian warriors of the four nations[2] in that quarter not being much short of fourteen thousand: not to advert to the combinations which a general Indian war might produce with the European powers with whom the tribes both north and south of the Ohio are connected.

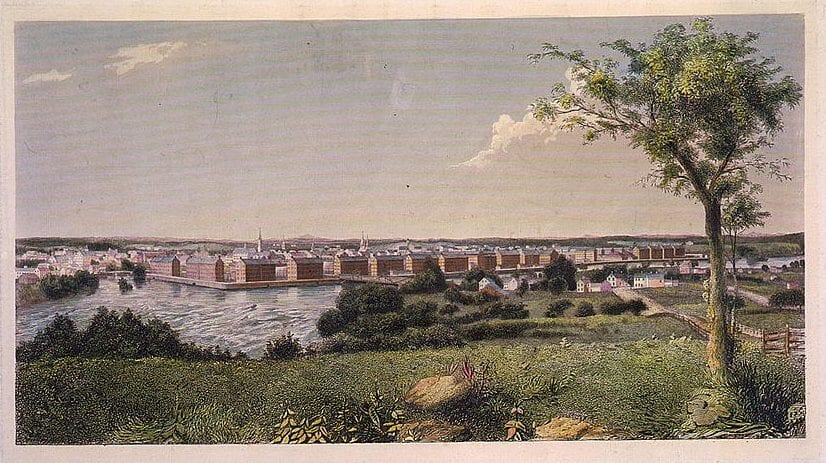

It seems that our own experience would demonstrate the propriety of endeavoring to preserve a pacific conduct in preference to a hostile one with the Indian tribes. The United States can get nothing by an Indian war, but they risk men, money, and reputation. As we are more powerful and more enlightened than they are, there is a responsibility of national character that we should treat them with kindness and even liberality. It is a melancholy reflection that our modes of population have been more destructive to the Indian natives than the conduct of the conquerors of Mexico and Peru. The evidence of this is the utter extirpation of nearly all the Indians in most populous parts of the Union. A future historian may mark the causes of this destruction of the human race in sable colors. Although the present government of the United States cannot with propriety be involved in the opprobrium yet it seems necessary however in order to render their attention upon this subject strongly characteristic of their justice, that some powerful attempts should be made to tranquilize the frontiers particularly those south of the Ohio. The situation of the settlements on Cumberland[3] loudly demand the interference and protection of government. It is true some unauthorized offensive operations have proceeded from thence against the lower Cherokee towns[4] and victims were sacrificed. Whether these victims were all warriors, or whether women and children were not involved in the destruction seems to merit inquiry.

Upon the most mature reflection the subscriber[5] has been able to bestow upon this subject arising from the experience of several years observation thereof he humbly conceives all attempts to preserve the peace with the Indian tribes will be found inadequate short of an arrangement somewhat like the following: to wit

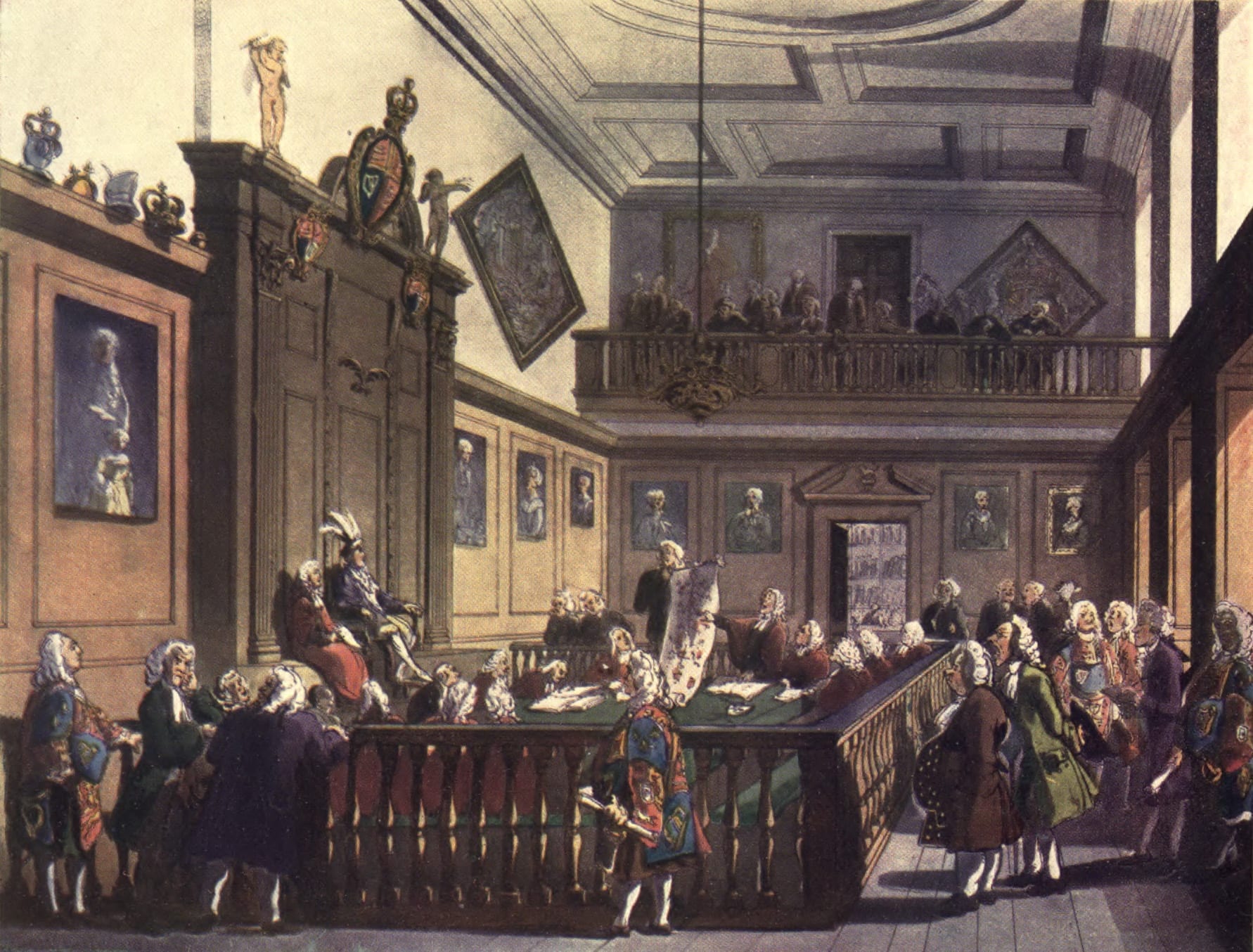

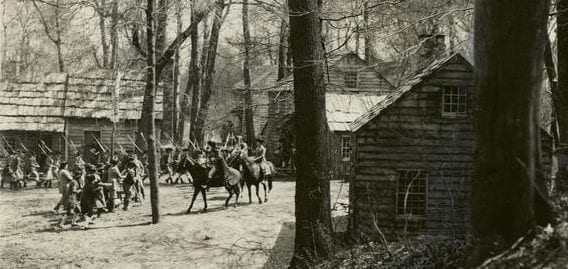

1. That a line of military posts at such distances as shall be directed be established upon the frontiers within the Indian boundary and out of the ordinary jurisdiction of any state; provided consent can be obtained for the purpose from the Indian tribes; that these posts be garrisoned with regular troops under the direction of the president of the United States.

2dly That if any murder or theft be committed upon any of the white inhabitants by an Indian known to belong to any Indian nation or tribe such nation or tribe shall be bound to deliver him or them up to the nearest military post in order to be tried and punished by a court-martial, or in failure thereof the United States will take satisfaction upon the nearest Indian town belonging to such nation or tribe.

3dly “That all persons who shall be assembled or embodied in arms on any lands belonging to Indians out of the ordinary jurisdiction of any State or of the Territory south of the Ohio for the purpose of warring against the Indians or of committing depredations upon any Indian town or persons or property shall thereby become liable and subject to the rules and articles of War which are or shall be established for the government of the troops of the United States.” This was a section of a bill which the Senate passed the last session entitled “An Act for the More Effectual Protection of the South Western Frontiers,” but it was disagreed to by the House.

If to this arrangement the expense should be objected it is to be remembered that the president of the United States in pursuance of law has authorized both the governor of Georgia and the governor of the South Western Territory[6] to establish a defensive protection, which amounts to a large sum annually.

Posts therefore requiring garrisons amounting to one thousand five hundred noncommissioned and privates for the whole South Western Frontiers from the St Marys[7] to the Ohio would probably be adequate to this object.

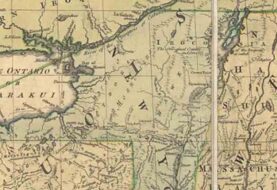

If the posts belonging to the United States and now occupied by the British north of the Ohio be soon delivered up, they, with a post at the Miami villages,[8] and posts of communication down the Wabash[9] on the south, and the Miami River to Lake Erie on the north, together with a post at Presque Isle,[10] would be a pretty adequate protection to the frontiers north of the Ohio and a curb to any Indian tribes, discontented without just cause, which it is presumed will never be afforded by the government of the United States.

If to these vigorous measures should be combined the arrangement of trade recommended to Congress[11] and the establishment of agents to reside in the principal Indian towns with adequate compensations it would seem that the government would then have made the fairest experiments of a system of justice and humanity, which, it is presumed could not possibly fail of being blessed with its proper effects—an honorable tranquility of the frontiers. All which is respectfully submitted to the president of the United States.

- 1. Knox uses the term “police” in a customary eighteenth-century way, meaning not just those individuals who enforce the law, but more generally all means of maintaining public order.

- 2. Possibly the Cherokees, Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Creeks.

- 3. The Cumberland River flows westward through the area that now forms the border between Kentucky and Tennessee.

- 4. Locations in southern Tennessee and northern Georgia to which Cherokees relocated to avoid westward-moving settlers.

- 5. Knox is referring to himself as the writer of the report.

- 6. What is now the state of Tennessee.

- 7. A river that forms part of the border between Georgia and Florida.

- 8. In what is now western Ohio.

- 9. The Wabash River runs from western Ohio south through what is now Indiana to the Ohio River.

- 10. Probably a reference to a location on Lake Erie, in Pennsylvania.

- 11. In Washington’s Annual Messages of 1793 and 1794, what we refer to today as the State of the Union Address.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.