Introduction

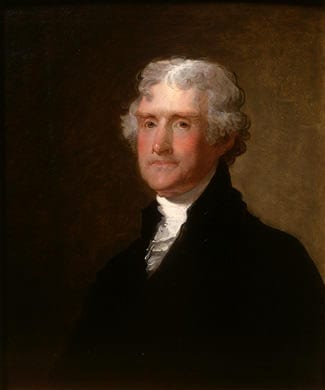

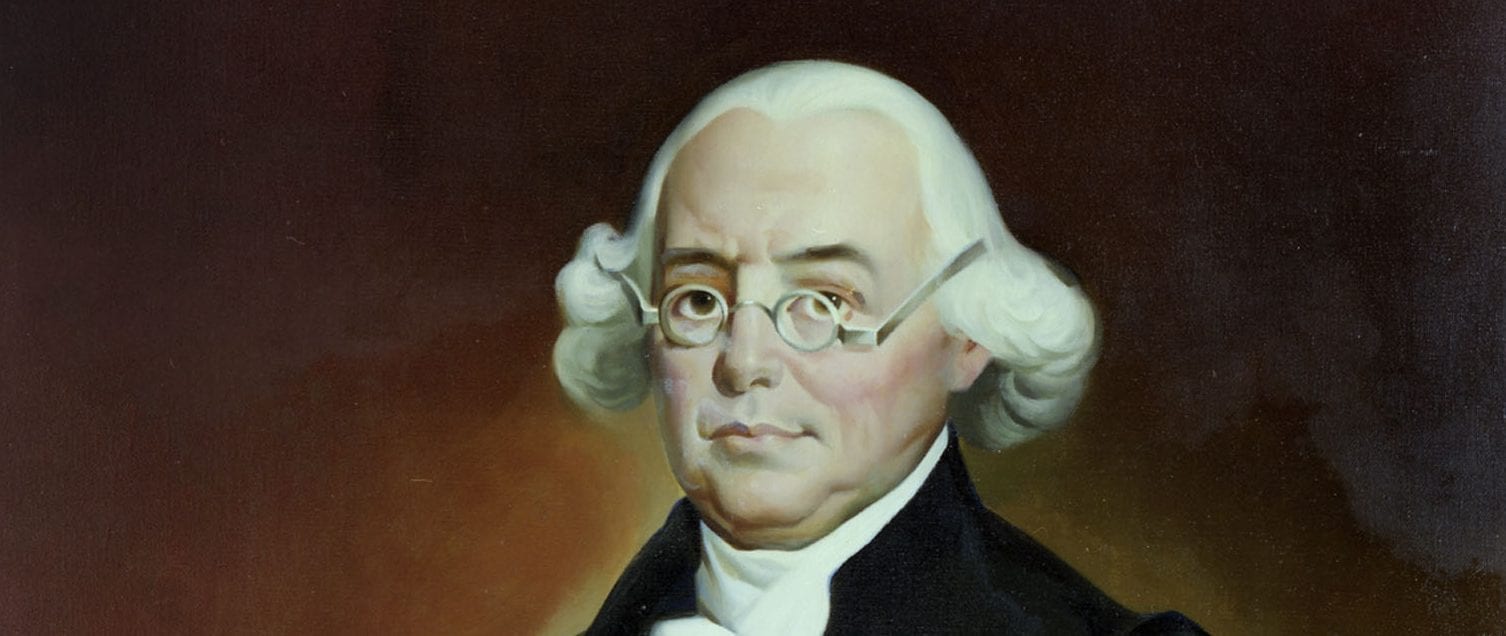

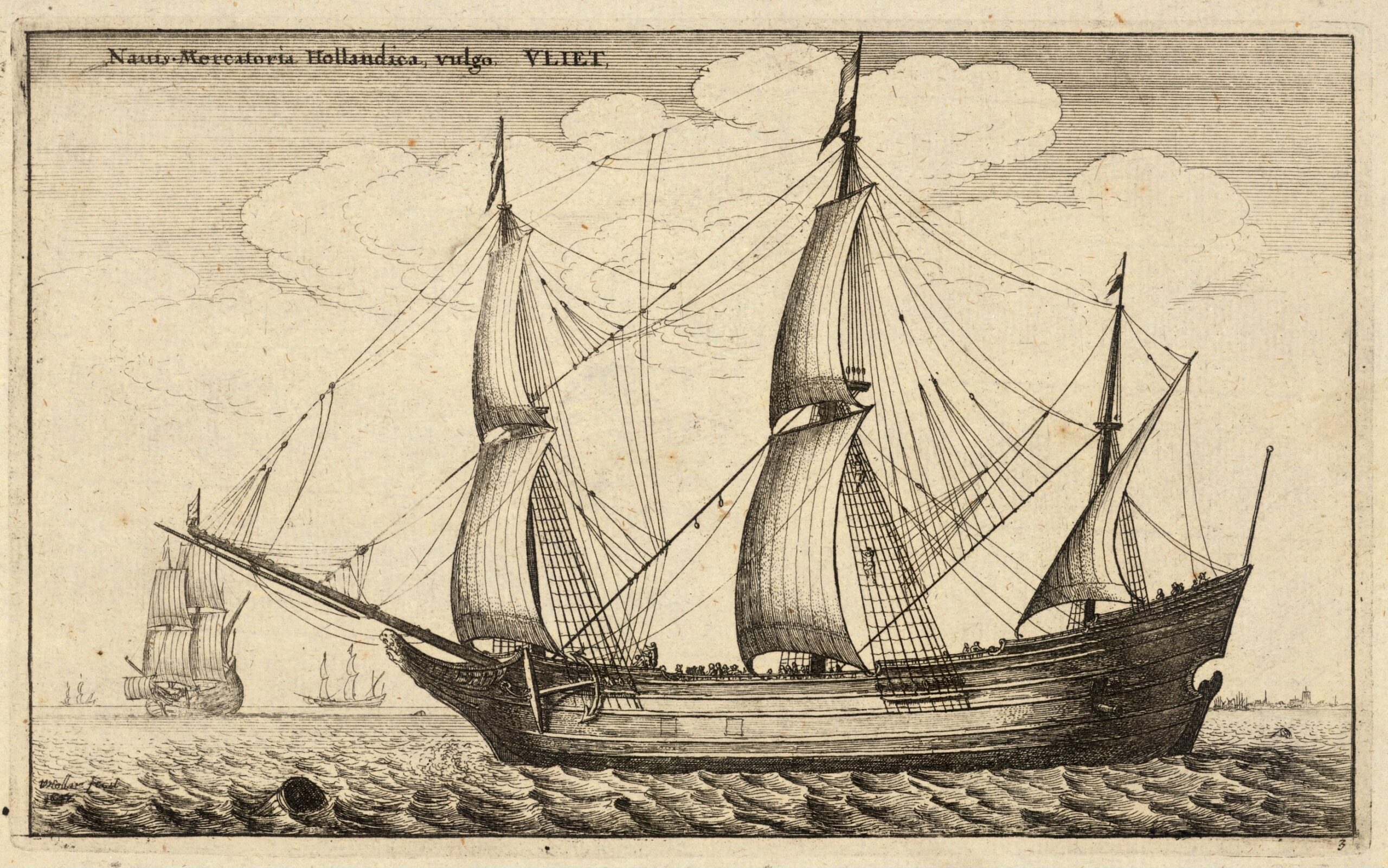

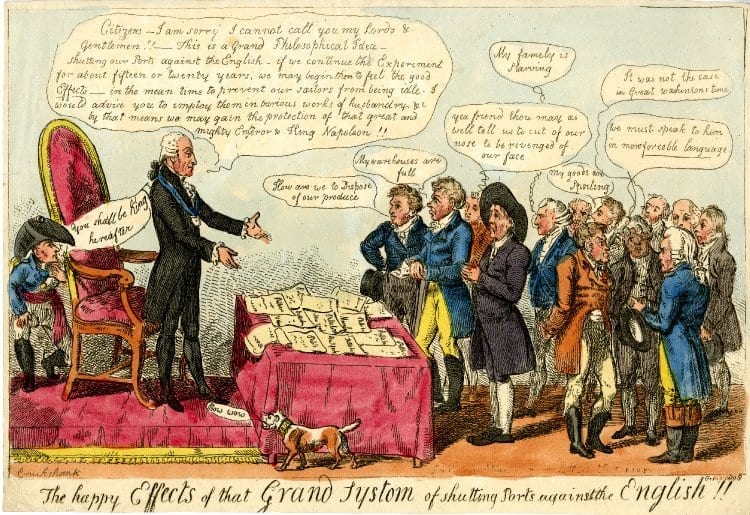

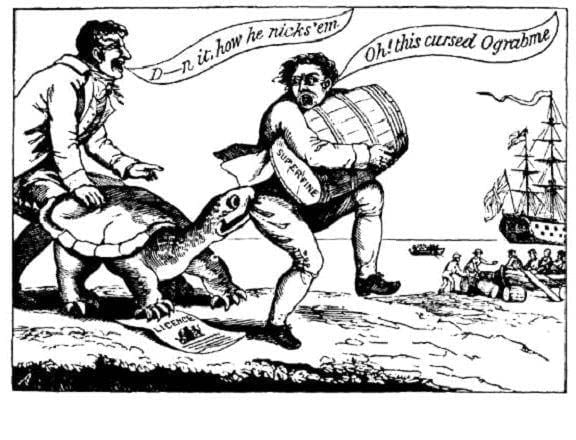

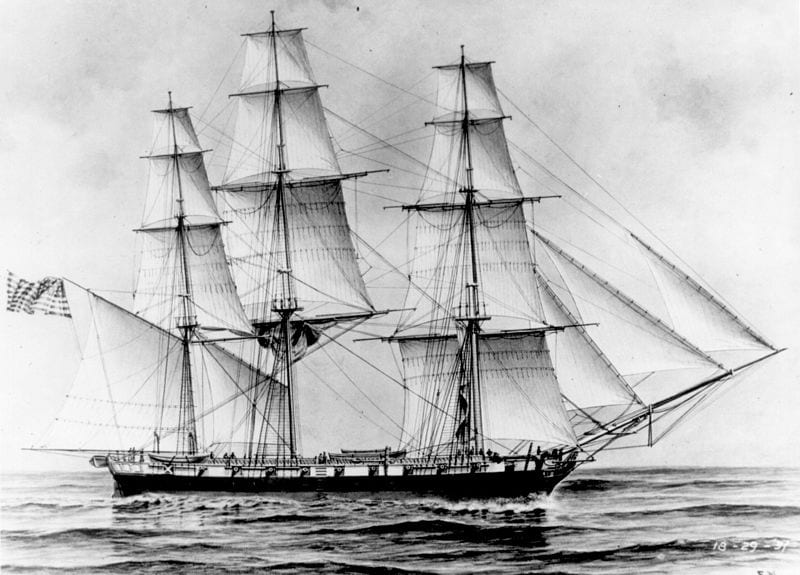

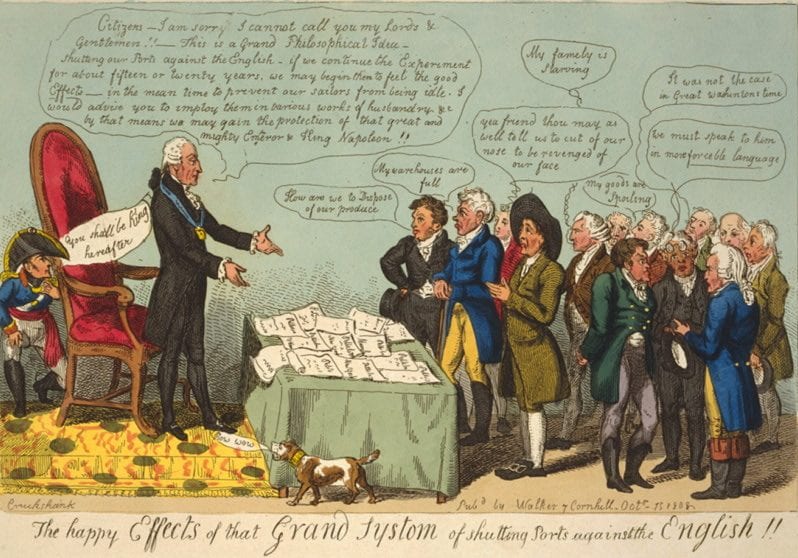

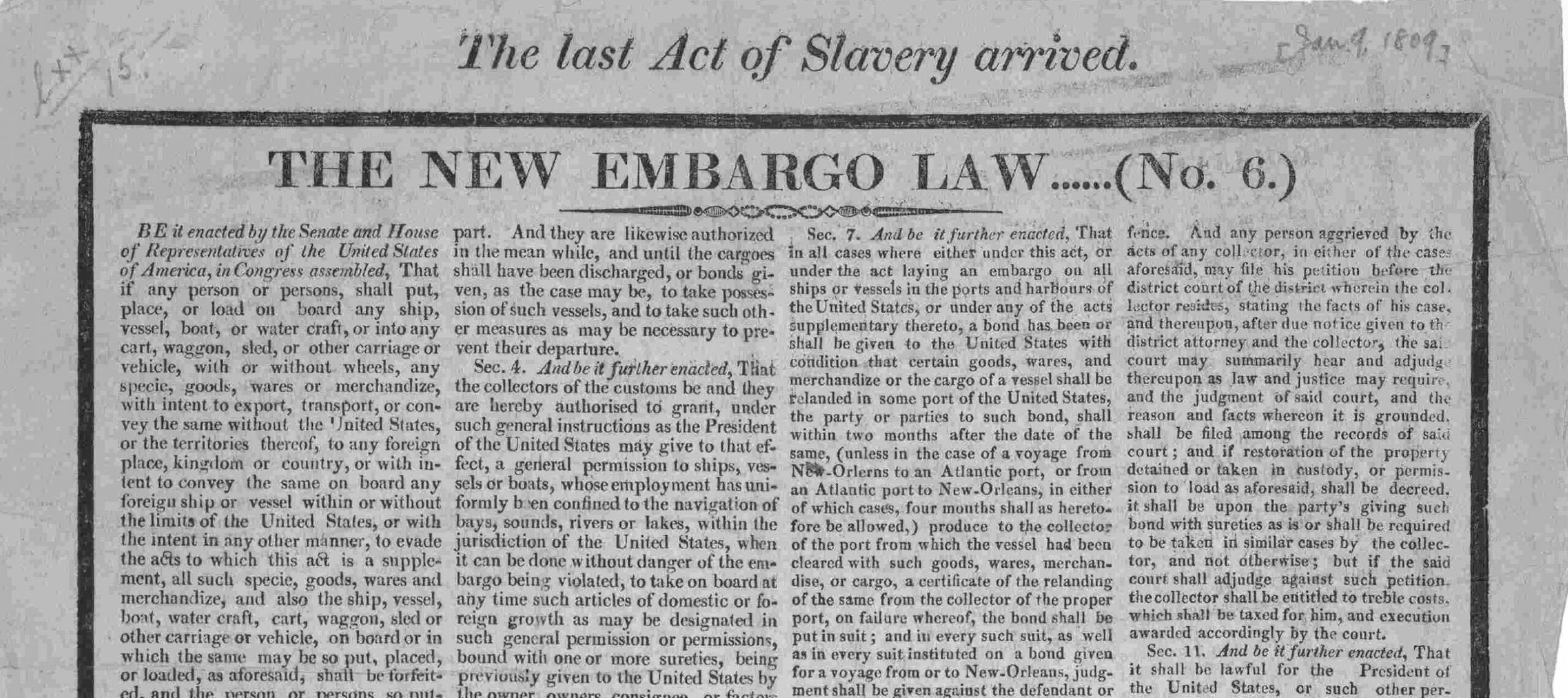

The trade embargoes put into place by Presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in an effort to keep the United States out of the Napoleonic Wars between France and Britain were particularly unpopular with the population of the New England states whose economic vitality depended largely upon international commerce. Madison’s decision to declare war on Great Britain in June 1812, although intended as a defense of American shipping and sailors being targeted by British warships, was similarly unpopular in the region. Indeed, the governors of the New England states largely refused Madison’s request to nationalize the state militia, on the grounds that it was an unconstitutional imposition on their right to defend their own borders and interests. Madison’s subsequent failure to prevent the British from blockading New England’s ports only exacerbated the political tensions.

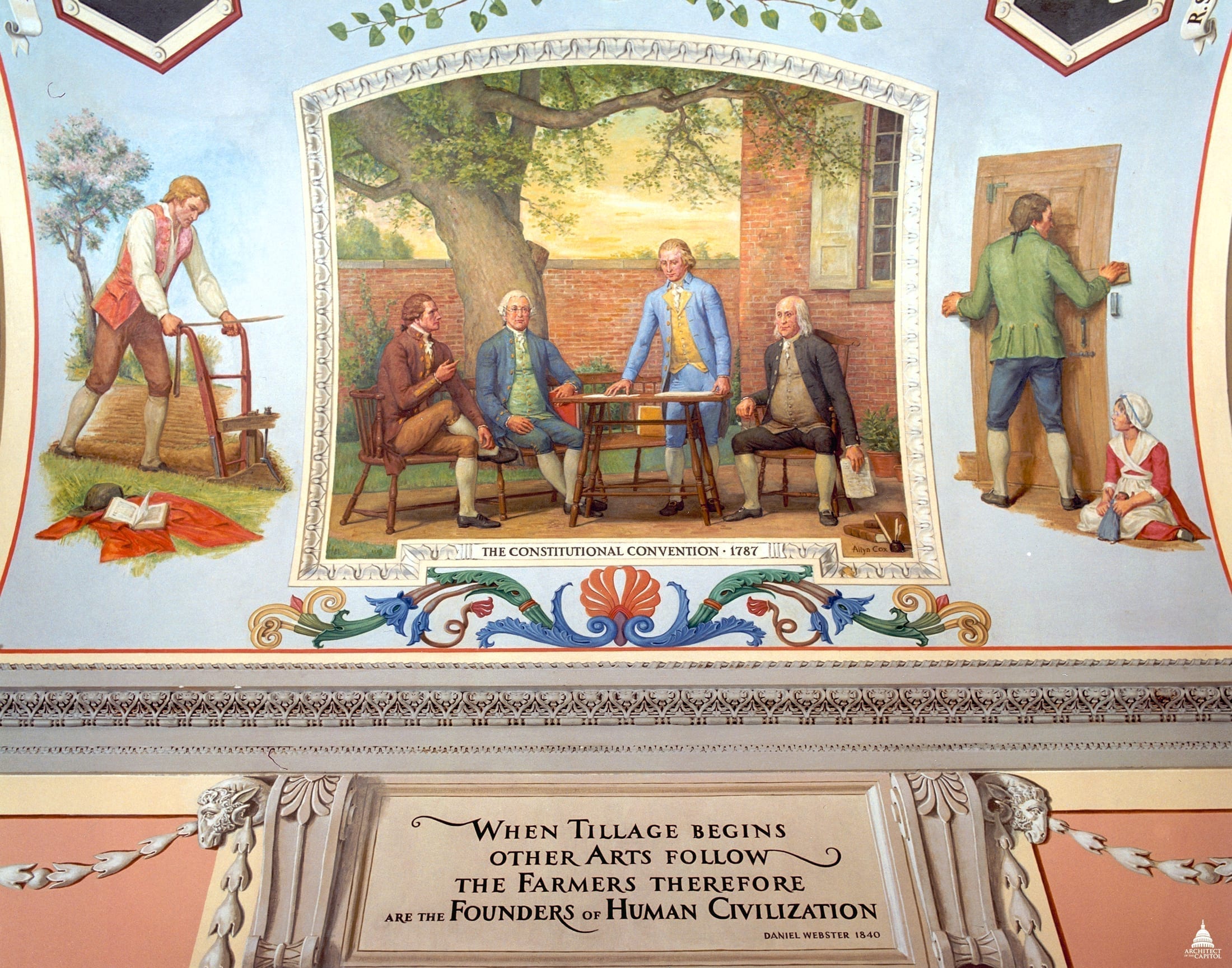

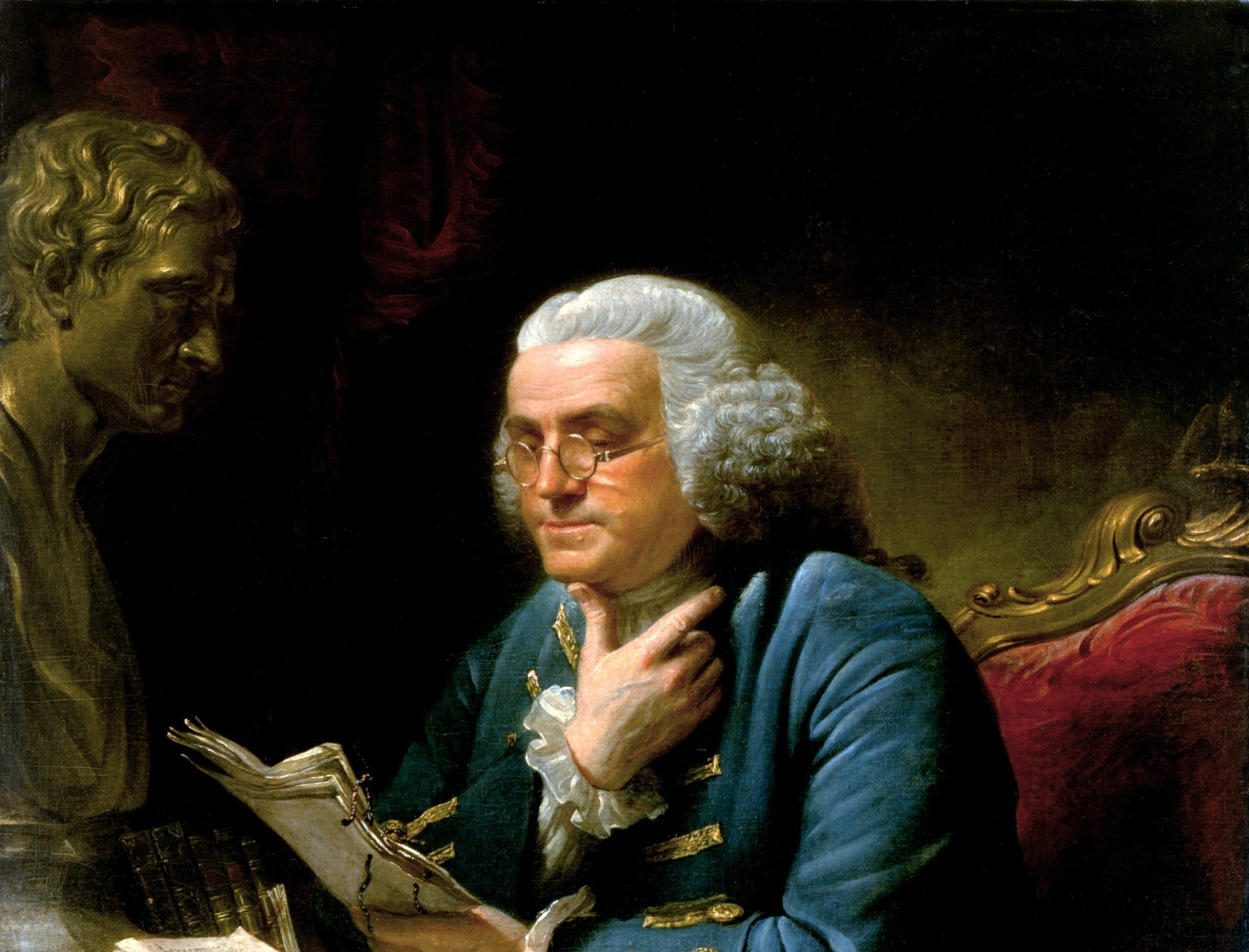

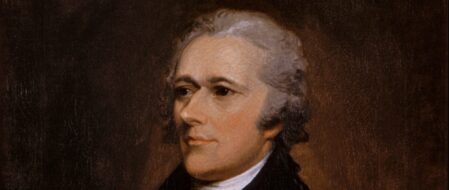

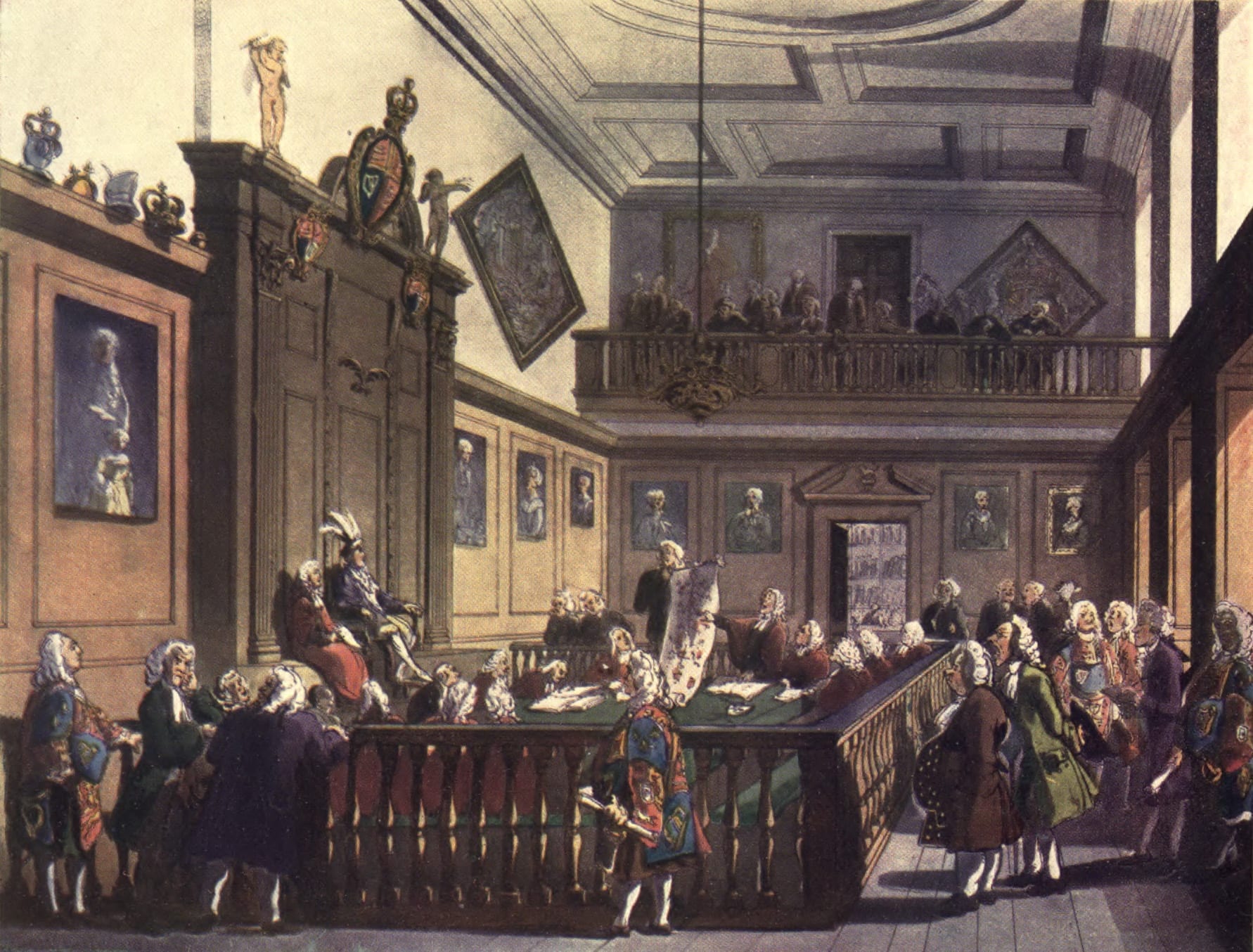

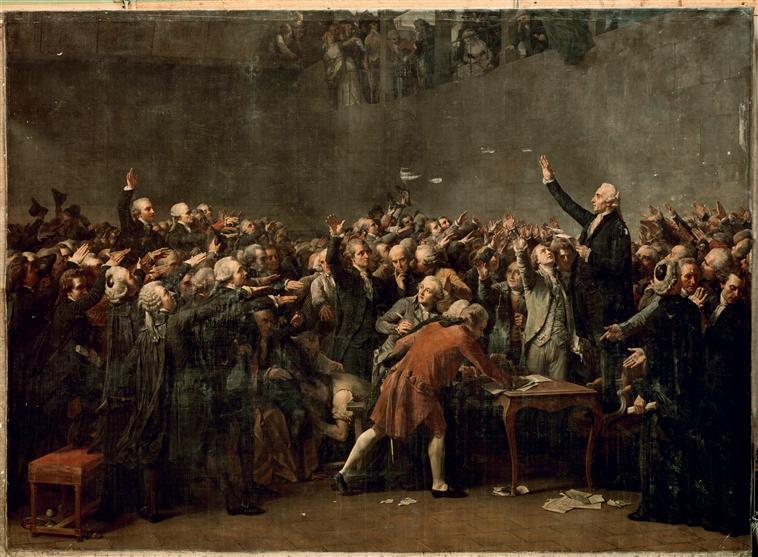

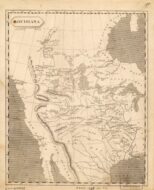

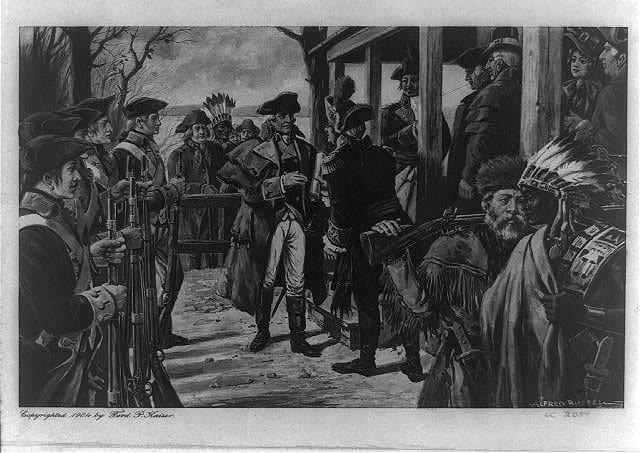

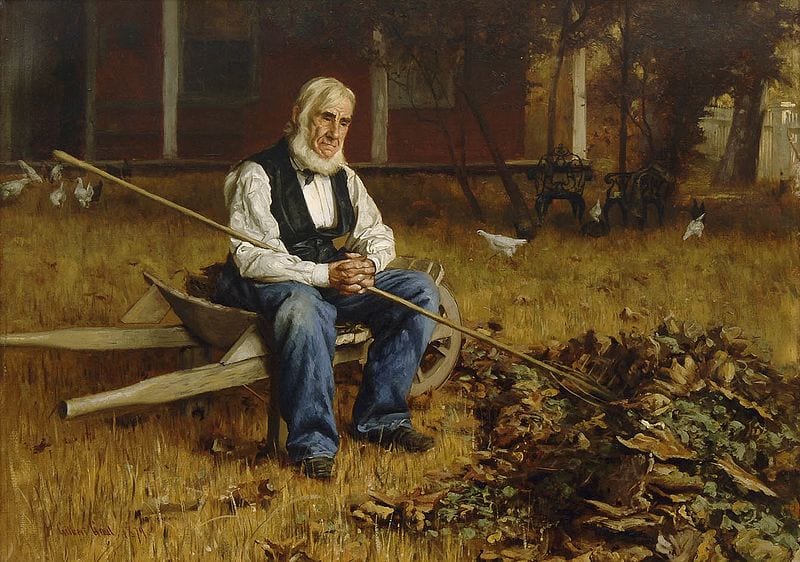

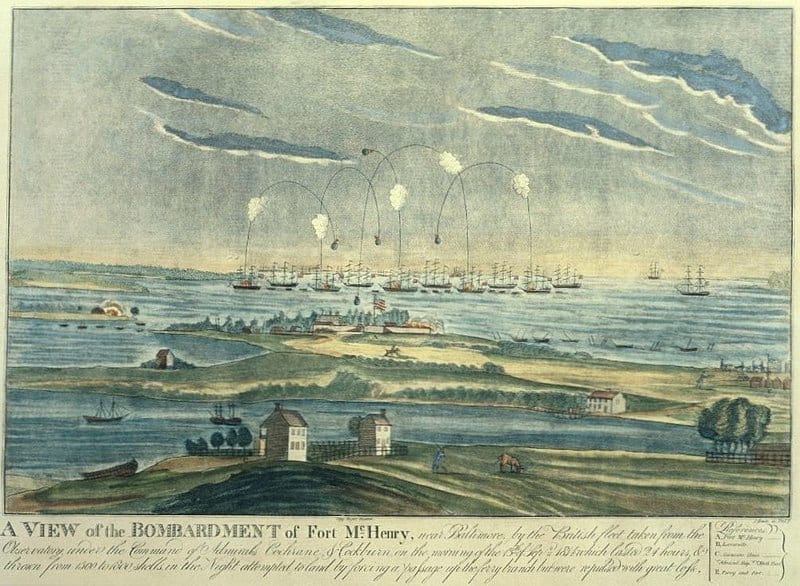

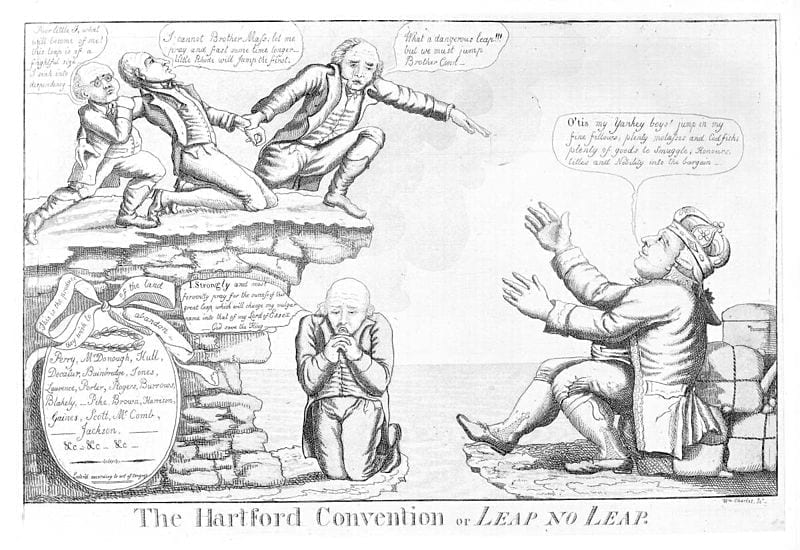

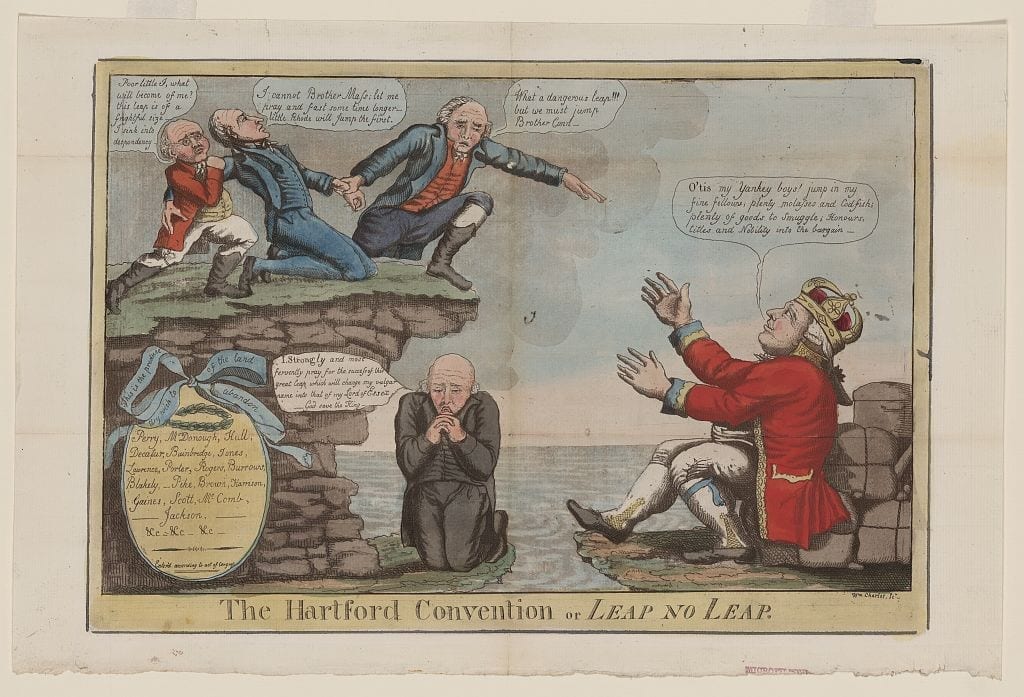

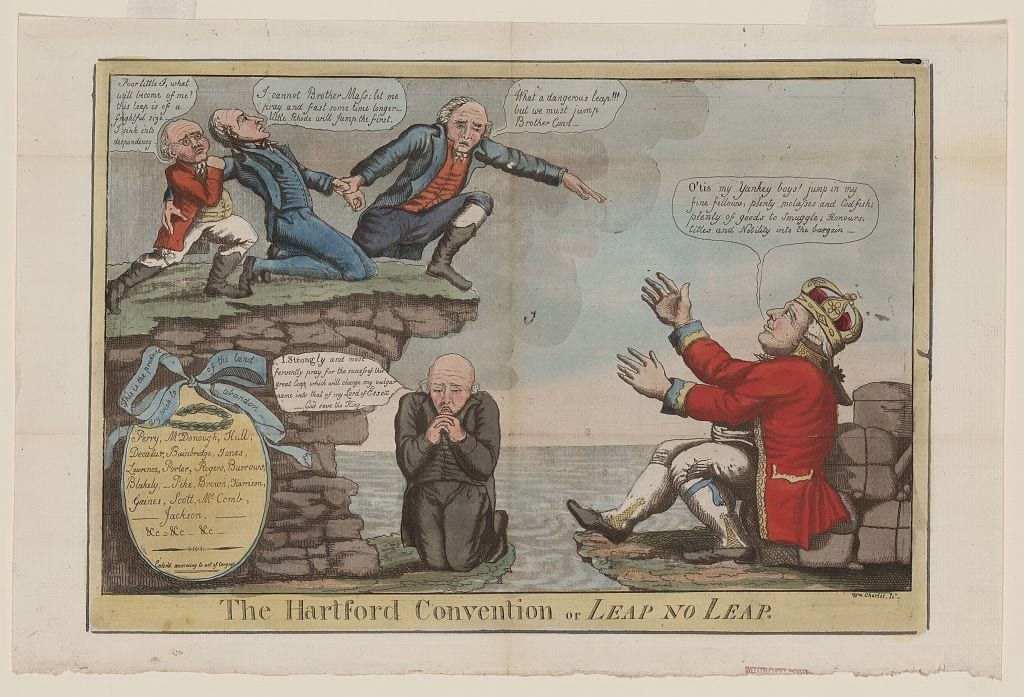

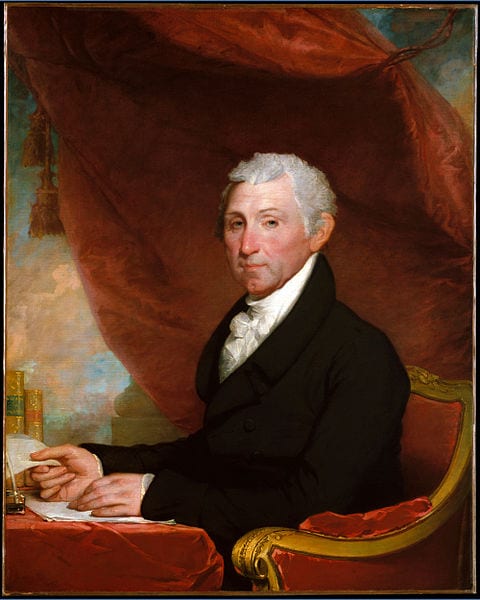

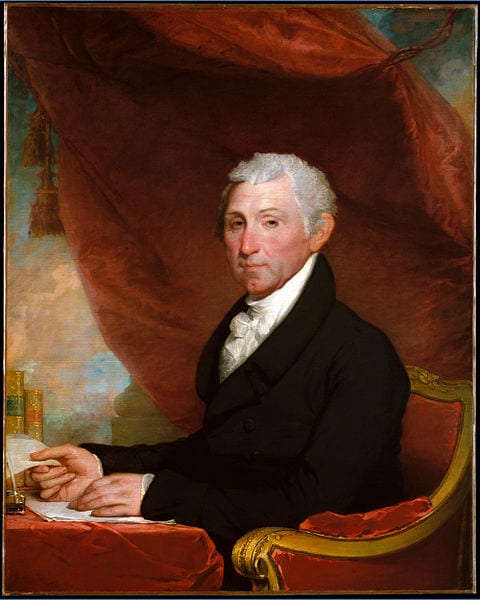

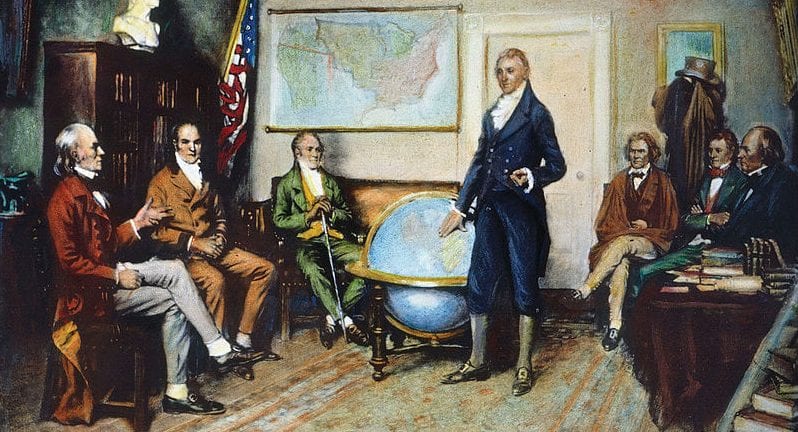

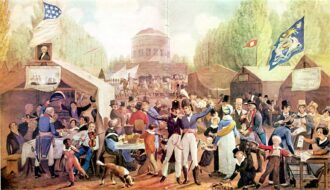

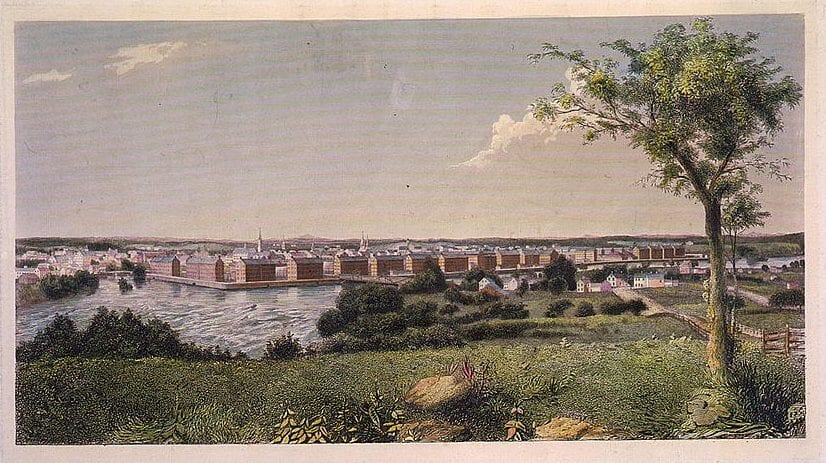

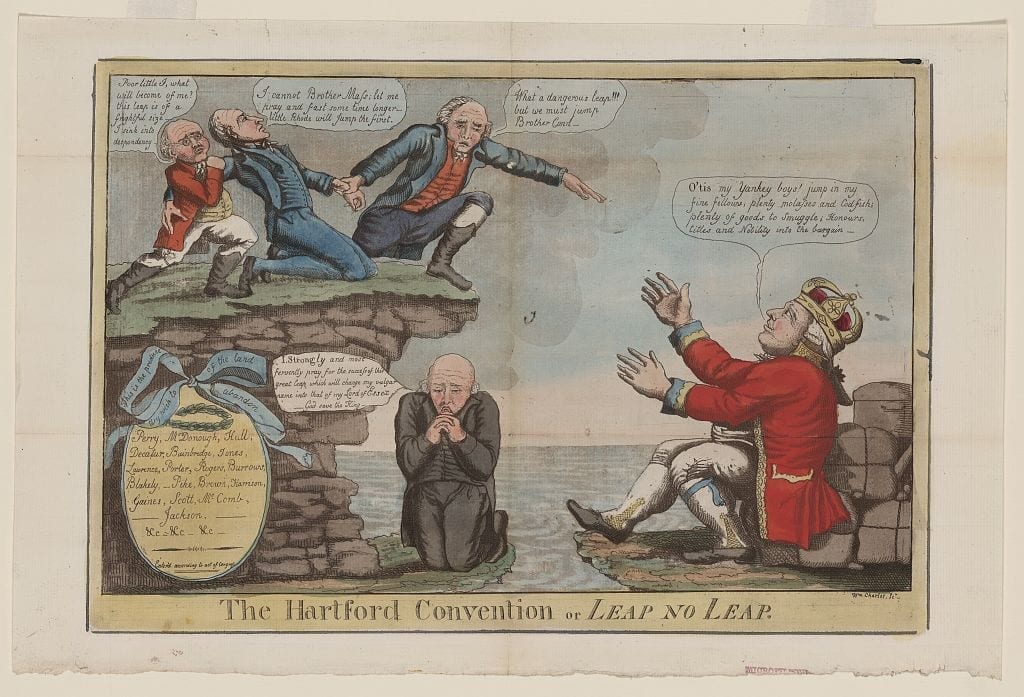

By late 1814, the situation had become so dire that a group of wealthy New England Federalists, led by Joseph Lyman, and others from Massachusetts felt justified in enjoining their state legislatures to call a regional convention to organize a formal protest of the administration’s war policy (Document A). Held in Hartford, Connecticut, from December 15, 1814–January 5, 1815, the convention garnered significant attention both prior to and during its sessions. To many observers, the convention seemed poised on the very edge of treason, as in the cartoon by William Charles, which depicts representatives of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island (the three New England States who dominated the Hartford Convention) poised on the edge of a cliff, indecisively looking toward the open arms of England’s King George III (Document 2; see also Documents 3-4).

The delegates to the convention held their meetings in such complete secrecy that no record of any speeches given or motions discussed on the floor survives. At the conclusion of their gathering, they did pass a series of resolutions that they intended to present to Congress in the spring of 1815. The urgency of the convention’s concerns was dissipated, however, when news reached the United States that the Treaty of Ghent ending the war had been signed in late December 1814. Their agenda rapidly faded into relative oblivion, to be remembered primarily as a specter of the dangers of rampant regionalism

Documents in this chapter are available separately by following the hyperlinks below:

- Noah Webster, The Origin of the Hartford Convention,1843

- William Charles, Leap or No Leap, c. 1814

- John Adams to William Plumer, December 4, 1814

- William H. Crawford to Jonathan Fisk, New England “Approaches the Confines of Treason,” December 8, 1814

- Report of the Hartford Convention, 1815

Noah Webster, “Origin of the Hartford Convention in 1814,” 18431

Few transactions of the federalists, during the early periods of our government, excited so much the angry passions of their opposers, as the Hartford Convention (so called), during the presidency of Mr. Madison. As I was present at the first meeting of the gentlemen who suggested such a convention; as I was a member of the House of Representatives in Massachusetts when the resolve was passed for appointing the delegates, and advocated that resolve; and further, as I have copies of the documents, which no other person may have preserved, it seems to be incumbent on me to present to the public the real facts in regard to the origin of the measure, which have been falsified and misrepresented.

After the war of 1812 had continued two years, our public affairs were reduced to a deplorable condition. The troops of the United States, intended for defending our sea-coast, had been withdrawn to carry on the war in Canada; a British squadron was stationed in the Sound2 to prevent the escape of a frigate from the harbor of New London, and to intercept our coasting trade; one town in Maine was in possession of the British force; the banks south of New England had all suspended the payment of specie; our shipping lay in our harbors embargoed, dismantled, and perishing; the treasury of the United States was exhausted to the last cent; and a general gloom was spread over the country.

In this condition of affairs, a number of gentlemen in Northampton in Massachusetts, after consultation, determined to invite some of the principal inhabitants of the three counties on the river, formerly composing the old county of Hamilton, to meet and consider whether any measures could be taken to arrest the continuance of the war, and provide for the public safety. In pursuance of this determination, a circular letter was addressed to several gentlemen in the three counties, requesting them to meet at Northampton. The following is a copy of the letter:

Northampton, January 5, 1814

Sir –

In consequence of the alarming state of our public affairs, and the doubts which have existed, as to the correct course to be pursued by the friends of peace, it has been thought advisable by a number of gentlemen in the vicinity, who have conversed together upon the subject, that a meeting should be called of some few of the most discreet and intelligent inhabitants of the old country of Hampshire, for the purpose of a free and dispassionate discussion touching our public concerns. . . .

We have therefore ventured to propose that it should be held at Col. Chapman’s in this town, on Wednesday, the nineteenth day of January current, at 12 o’clock in the forenoon, and earnestly request your attendance at the above time and place, for the purpose before stated.

With much respect, I am, sir, your obedient servant,

Joseph Lyman

In compliance with the request in this letter, several gentlemen met at Northampton, on the day appointed, and after a free conversation on the subject of public affairs, agreed to send to the several towns in the three counties on the river, the following circular address.

Sir –

The multiplied evils in which the United States have been involved by the measures of the late and present administration, are subjects of general complaint, and in the opinion of our wisest statesmen, call for some effectual remedy. His excellency, the governor of the commonwealth, in his address to the General Court, at the last and present session, has stated, in temperate but clear and decided language, his opinion of the injustice of the present war, and intimated that measures ought to be adopted by the legislature to bring it to a speedy close. He also calls the attention of the legislature to some measures of the general government, which are believed to be unconstitutional. In all the measures of the general government, the people of the United States have a common concern; but there are some laws and regulations which call more particularly for the attention of the Northern states, and are deeply interesting to the peoples of this commonwealth. Feeling this interest, as it respects the present and future generations, a number of gentlemen from various towns in the old country of Hampshire, have met and conferred on the subject, and upon full conviction that the evils we suffer are not wholly of a temporary nature, springing from the war, but some of them of a permanent character, resulting from a perverse construction of the constitution of the United States, we have thought it a duty we owe to our country, to invite the attention of the good people of the counties of Hampshire, Hampden, and Franklin, to the radical causes of these evils.

We know indeed that a negotiation for peace has been recently set on foot, and peace will remove many public evils. It is an event we ardently desire. But when we consider how often the people of the country have been disappointed in their expectations of peace, and of wise measures; and when we consider the terms which our administration has hitherto demanded, some of which it is certain cannot be obtained, and some of which, in the opinion of able statesmen, ought not to be insisted on, we confess our hopes of a speedy peace are not very sanguine

But still, a very serious question occurs, whether without an amendment of the federal constitution, the Northern and commercial states can enjoy the advantages to which their wealth, strength, and white population justly entitle them. By means of the representation of slaves, the Southern states have an influence in our national councils, altogether dispro-portionate to their wealth, strength, and resources; and we presume it to be a fact capable of demonstration, that for about twenty years past, the United States have been governed by a representation of about two fifths of the actual property of the country

In addition to this, the creation of new states in the south, and out of the original limits of the United States, has increased the Southern interest, which has appeared so hostile to the peace and commercial prosperity of the Northern states. This power, assumed by Congress, of bringing into the Union new states, at the time of the federal compact, is deemed arbitrary, unjust, and dangerous, and a direct infringement of the constitution. This is a power which may hereafter be extended, and the evil will not cease with the establishment of peace. We would ask then, ought the Northern states to acquiesce in the exercise of this power? To what consequences would it lead? How can the people of the Northern states answer to themselves and to their posterity, for an acquiescence in the exercise of this power, that augments an influence already destructive of our prosperity, and will, in time, annihilate the best interests of the Northern people?

There are other measures of the general government, which, we apprehend, ought to excite serious alarm. The power assumed to lay a permanent embargo appears not to be constitutional, but an encroachment on the rights of our citizens, which calls for decided opposition. It is a power, we believe, never before exercised by a commercial nation; and how can the Northern states, which are habitually commercial, and whose active foreign trade is so necessarily connected with the interest of farmer and mechanic, sleep in tranquility under such a violent infringement of their rights? But this is not all. The late act imposing an embargo, is subversive of the first principles of civil liberty. The trade coast-wise between different ports in the same state, is arbitrarily and unconstitutionally prohibited; and the subordinate officers of government are vested with powers altogether inconsistent with our republican institutions. It arms the President and his agents with complete control of persons and property, and authorizes the employment of military force to carry its extraordinary provisions into execution.

We forbear to enumerate all the measures of the federal government, which we consider as violations of the constitution, and encroachments upon the rights of the people, and which bear particularly hard upon the commercial people of the north. But we would invite our fellow citizens to consider whether peace will remedy our public evils, without some amendments of the constitution, which shall secure to the Northern states their due weight and influence in our national councils.

The Northern states acceded to the representation of slaves as a matter of compromise, upon the express stipulation in the constitution that they should be protected in the enjoyment of their commercial rights. These stipulations have been repeatedly violated; and it cannot be expected that the Northern states should be willing to bear their proportion of the burdens of the federal government without enjoying the benefits stipulated

If our fellow citizens should concur with us in opinion, we would suggest whether it would not be expedient for the people in town meetings, to address memorials to the General Court, at their present session petitioning that honorable body to propose a convention of all the Northern and commercial states, by delegates to be appointed by their respective legislatures, to consult upon measures in concert, for procuring such alterations in the federal constitution, as will give to the Northern states a due proportion of representation, and secure them from the future exercise of such powers injurious to their commercial interests; or if the General Court shall see fit, that they should pursue such other course as they, in their wisdom, shall deem best calculated to effect the objects.

The measure is of such magnitude that we apprehend a concert of states will be useful, and even necessary to procure the amendments proposed; and should the people of the several states concur in this opinion, it would be expedient to act on the subject without delay.

We request you, sir, to consult with your friends on the subject, and if it should be thought advisable, to lay this communication before the people of your town. In behalf, and by direction of the gentlemen assembled,

Joseph Lyman, Chairman

In compliance with the request and suggestions in this circular, many town meetings were held, and with great unanimity addresses and memorials were voted to be presented to the General Court, stating the sufferings of the country in consequence of the embargo, the war, and arbitrary restrictions on our coasting trade, with the violations of our constitutional rights, and requesting the legislature to take measures for obtaining redress, either by a convention of delegates from the Northern and commercial states, or by such other measures as they should judge to be expedient.

These addresses and memorials were transmitted to the General Court, then in session; but as commissioners had been sent to Europe for the purpose of negotiating a treaty of peace, it was judged advisable not to have any action upon them, until the result of the negotiation should be known. But during the following summer, no news of peace arrived; and the distresses of the country increasing, and the sea-coast remaining defenseless, Governor Strong summoned a special meeting of the legislature in October, in which the petitions of the towns were taken into consideration, and resolve was passed, appointing delegates to a convention to be held in Hartford. The subsequent history of that convention is known by their report.3

This measure of resorting to a convention for the purpose of arresting the evils of a bad administration, roused the jealousy of the advocates of the war, and called forth the bitterest invectives. The convention was represented as a treasonable combination, originating in Boston, for the purpose of dissolving the Union. But citizens of Boston had no concern in originating the proposal for a convention; it was wholly the project of the people in old Hampshire County; as respectable and patriotic republicans as ever trod the soil of a free country. The citizens who first assembled in Northampton, convened under the authority of the bill of rights which declares, that the people have a right to meet in a peaceable manner and consult for the public safety. The citizens had the same right then to meet in convention, as they have now; the distresses of the country demanded extraordinary measures for redress; the thought of dissolving the Union never entered the head of any of the projectors, or of the members of the convention; the gentlemen who composed it, for talents and patriotism, have never been surpassed by any assembly in the United States; and beyond a question, the appointment of the Hartford Convention had a very favorable effect in hastening the conclusion of a treaty of peace.

All reports which have been circulated respecting the evil designs of that convention, I know to be the foulest misrepresentations. . . .

Back to TopWilliam Charles, Leap or No Leap, c. 18154

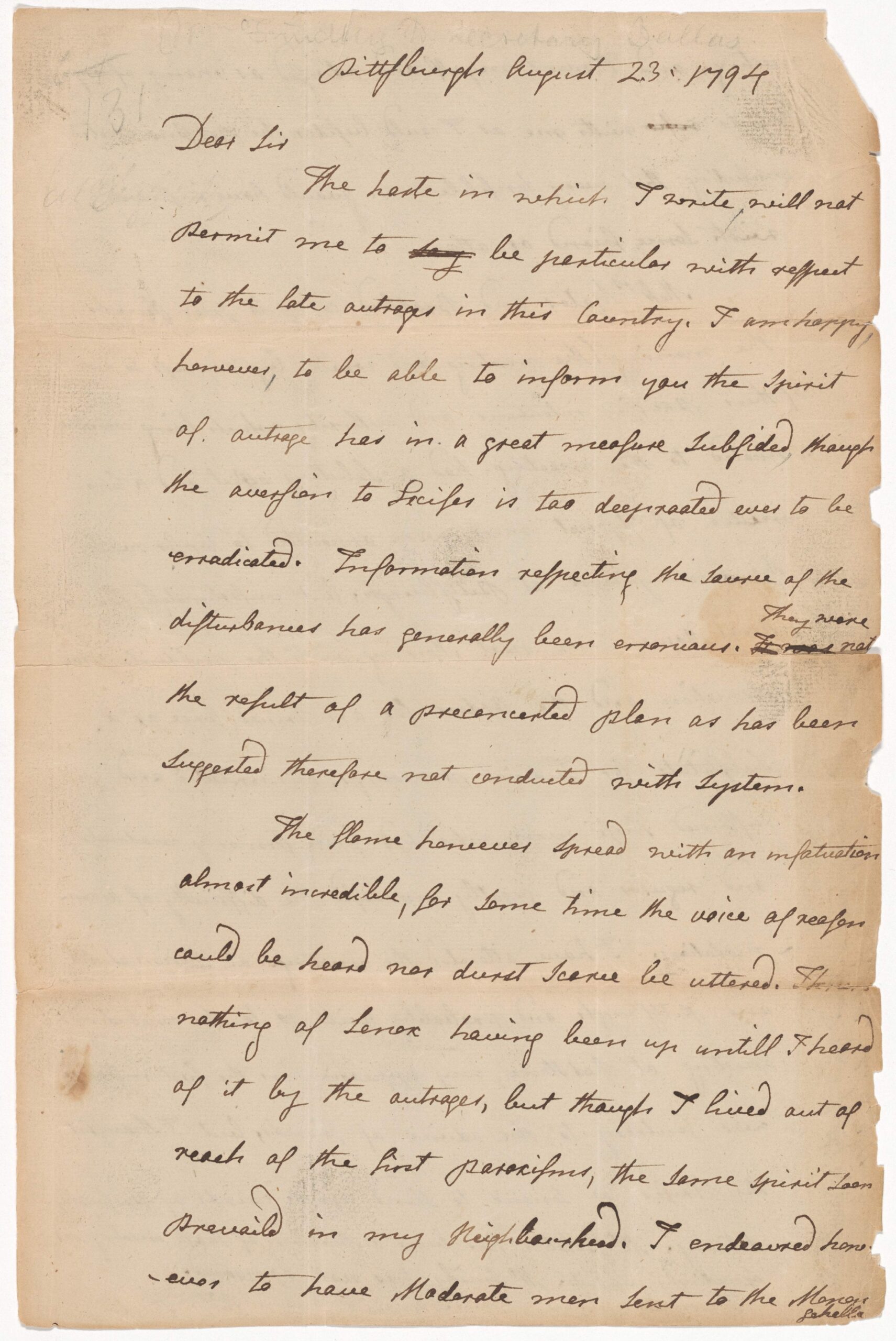

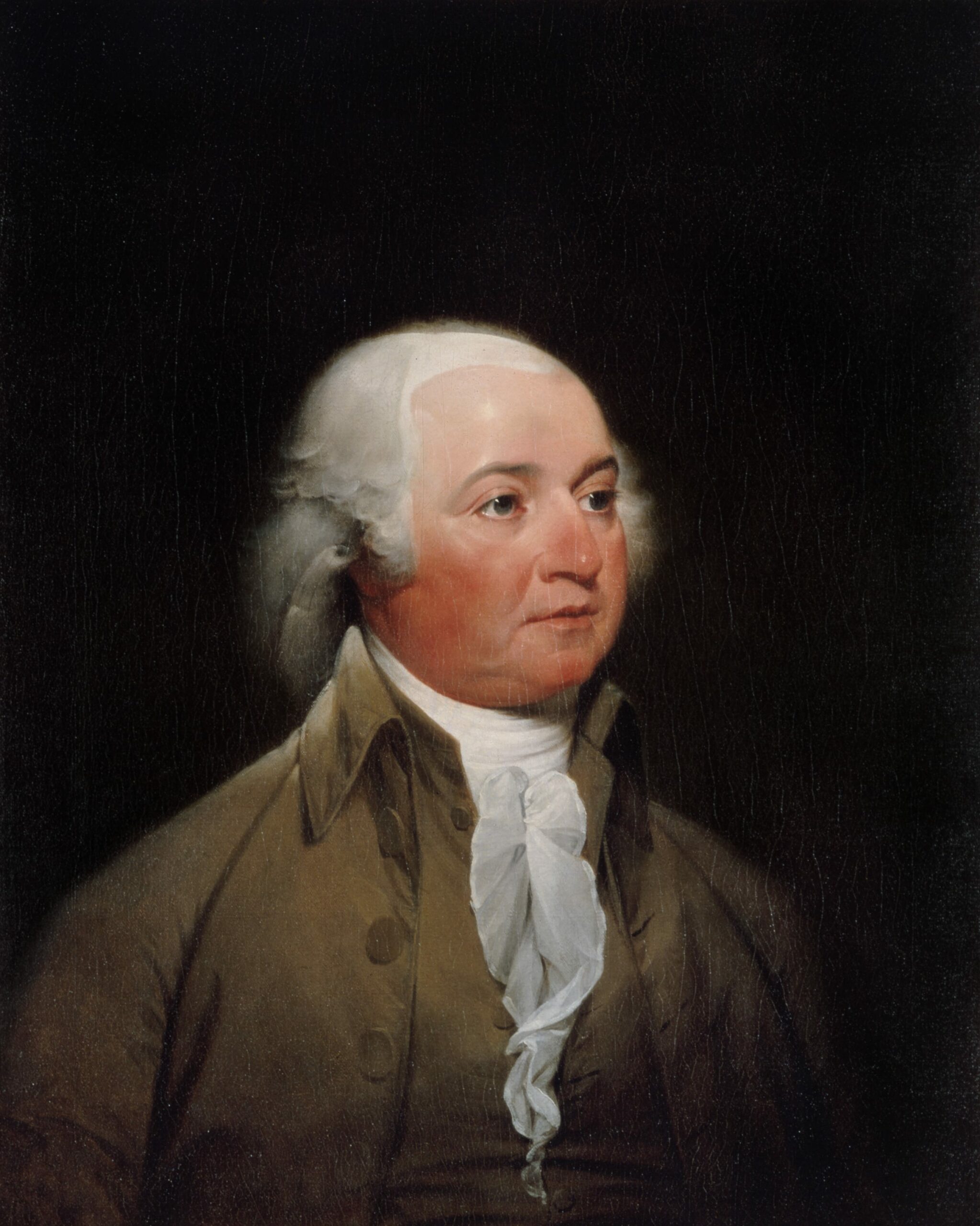

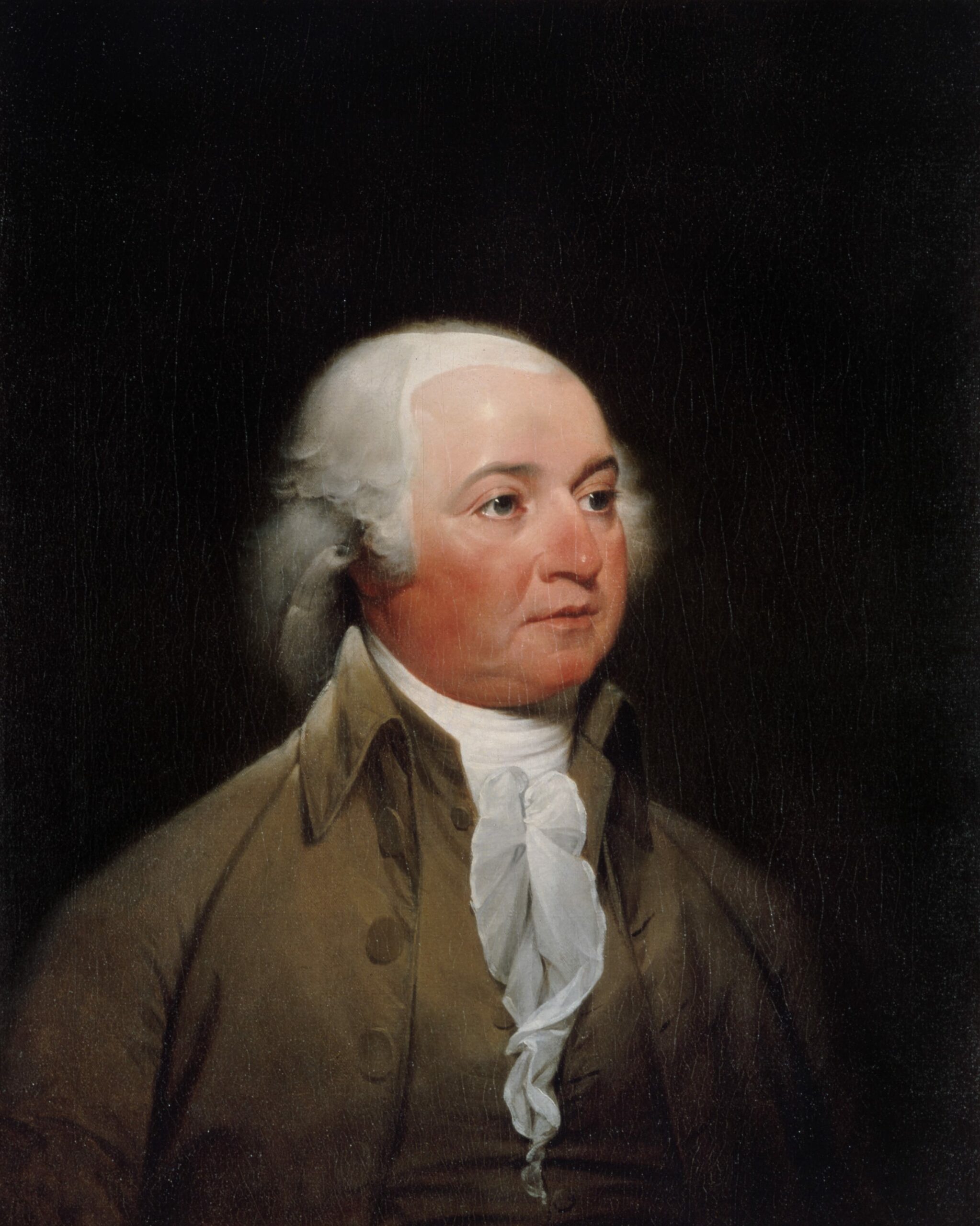

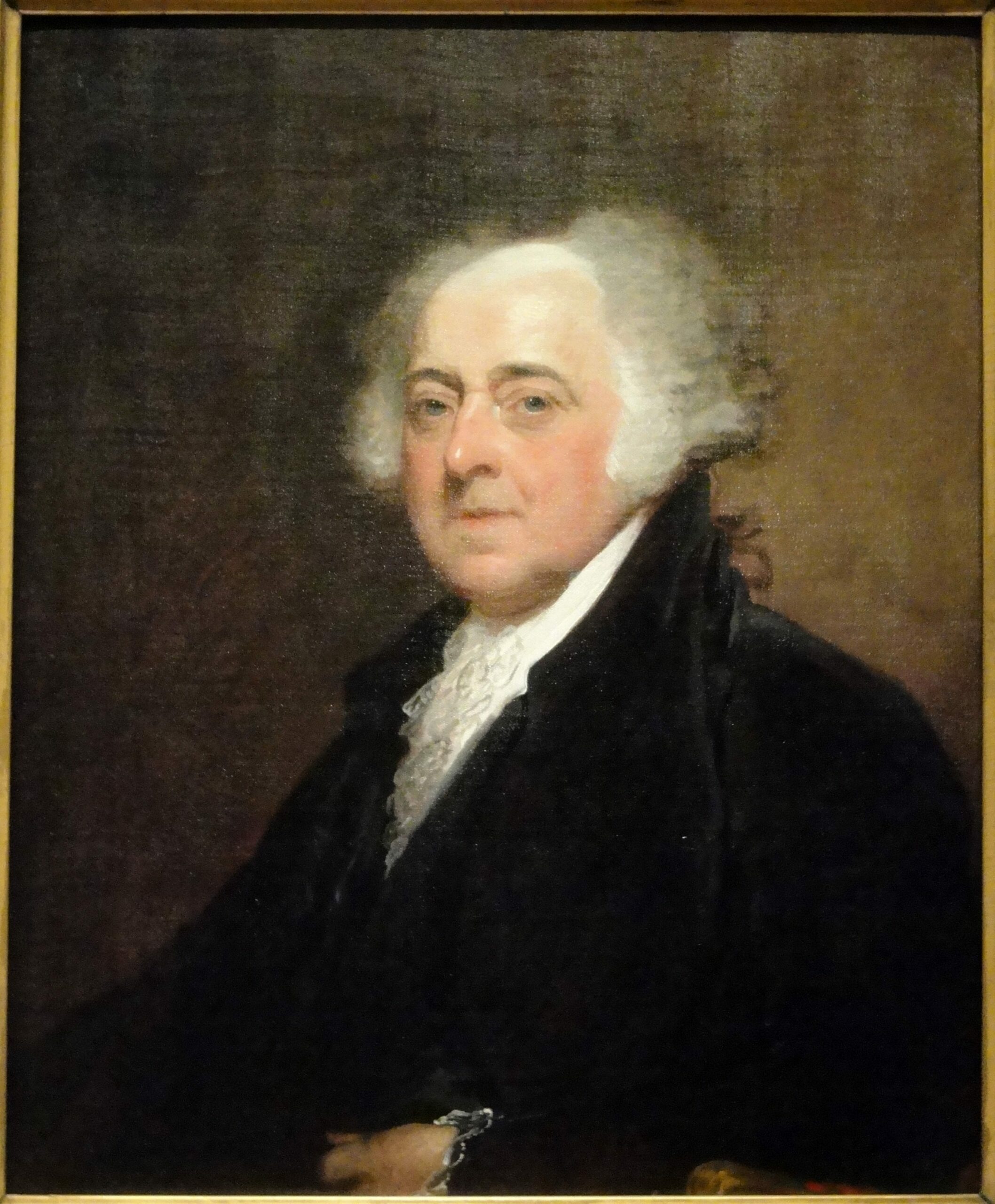

John Adams to William Plumer, December 4, 18145

Dear Sir

. . . The Convention at Hartford is to resemble the Congress at Vienna; at least as much as an Ignis fatuus6 resembles a Volcano. Already we are informed that Mr. Randolph and Mr. Harper are at New York on their way to the grand Caucus. The Delegates from your Chester will meet Philosophers, Divines, Lawyers, Physicians, Merchants, Farmers, fine Ladies, Pedlars and Beggars, from various parts of the World not excepting Vermont, or Canada, as well as the legislative Sages from Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. You see, I cannot write soberly upon this subject. It is ineffably ridiculous. As an electioneering, a canvassing, or more expressively, a parliamenteering intrigue it is a cunning device, but even in this view it is the cunning of the ostrich.

Do they mean to declare New England neutral? New England neutrality has been the cause of the War. New England canvass, New England seamen, have excited British jealousy and alarmed British fears. Britain had rather Spain, France, Holland, or Russia should be neutral, than New England. Britain dreads a neutral more than a belligerent. Canvass and Seamen are the enemies that Britain fears more than all the Armies of Europe.

Do they mean to erect New England into an independent Power?

Let me see! New England is a Nation, a sovereign, a power, at war with Nova Scotia, Canada, fourteen states to the Southward and Westward of her, and Great Britain at the same time. This new state which has taken its equal station among the nations of the earth, sends ambassadors to London and to Washington to make peace and solicit neutrality. What will be their reception? Will they make their public entry like Venetian ambassadors? Their ambassadors are received at St. James’s or Carlton House. They demand neutrality. “What do you mean by Neutrality? Says the British Minister? Do you mean to fish, and carry your fish to France, Spain, Portugal, and Italy, and to the French, Spanish, Dutch, Danish, Swedish, and English Islands in the West Indies? Do you mean to trade to China, India, and carry your Cargoes to all Europe and all the World? even to Canada, Nova Scotia, and your own Southern States? or do you mean to unite with us, become loyal Subjects and go to war with all our Enemies”? I wish I could pursue this conference in detail. But forces fail. . . .

Back to TopWilliam H. Crawford to Jonathan Fisk, New England “approaches the confines of treason,” December 8, 18147

Paris 8th Decre 1814

Dear Sir.

. . . From the letters & News Papers which I have Recd by the Fingal, & the Ajax, public spirit Seems to be good, everywhere, but in old Massachusetts.

The attempt to form a New England confederacy under the pretext, that the general government refuses them protection, when they have labored assiduously to prevent the execution of the measures which were calculated to afford that protection, approaches the confines of treason. The execution of their threat to withhold their taxes, & to apply them for their defense, will be an overt act which will rend the veil which their hypercritical canting has hitherto thrown over their insidious measures. Their mode of calling a convention is certainly irregular & unconstitutional. I do not believe that they will do more than menace. Whilst New York remains sound, the New England states dare not move, even if they were united. The federalism of Connecticut, is constitutional, & will not be seduced by the intentional flattery of selecting one of its towns, for the assembling of this unconstitutional Convention. Independent of the steady habits of Connecticut, it is notorious that the majority in the other States, is a very inconsiderable one, upon general questions—upon the question of separation, or of performing any act which amounts to treason or Rebellion, these majorities would immediately dwindle into contemptible minorities. There is therefore no danger of Rebellion or treason. The Essex Junto8 disappointed in all their schemes of ambition; convinced of their incapacity to carry the people with them in their treasonable views, will not dare to act, but will continue to snarl and shew their teeth.

Back to TopReport of the Hartford Convention, 18159

The Delegates from the Legislatures of the States of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode-Island, and from the Counties of Grafton and Cheshire in the State of New-Hampshire and the County of Windham in the State of Vermont, assembled in Convention, beg leave to report the following result of their conference.

The Convention is deeply impressed with a sense of the arduous nature of the commission which they were appointed to execute, of devising the means of defense against dangers, and of relief from oppressions proceeding from the act of their own Government, without violating constitutional principles, or disappointing the hopes of a suffering and injured people. To prescribe patience and firmness to those who are already exhausted by distress, is sometimes to drive them to despair, and the progress towards reform by the regular road, is irksome to those whose imaginations discern, and whose feelings prompt, to a shorter course. But when abuses, reduced to system and accumulated through a course of years have pervaded every department of Government, and spread corruption through every region of the State; when these are clothed with the forms of law, and enforced by an Executive whose will is their source, no summary means of relief can be applied without recourse to direct and open resistance. This experiment, even when justifiable, cannot fail to be painful to the good citizen; and the success of the effort will be no security against the danger of the example. Precedents of resistance to the worst administration, are eagerly seized by those who are naturally hostile to the best. Necessity alone can sanction a resort to this measure; and it should never be extended in duration or degree beyond the exigency, until the people, not merely in the fervor of sudden excitement, but after full deliberation, are determined to change the Constitution.

It is a truth, not to be concealed, that a sentiment prevails to no inconsiderable extent, that Administration have given such constructions to that instrument, and practiced so many abuses under color of its authority, that the time for a change is at hand. Those who so believe, regard the evils which surround them as intrinsic and incurable defects in the Constitution. They yield to a persuasion, that no change, at any time, or on any occasion, can aggravate the misery of their country. This opinion may ultimately prove to be correct. But as the evidence on which it rests is not yet conclusive, and as measures adopted upon the assumption of its certainty might be irrevocable, some general considerations are submitted, in the hope of reconciling all to a course of moderation and firmness, which may save them from the regret incident to sudden decisions, probably avert the evil, or at least insure consolation and success in the last resort.

The Constitution of the United States, under the auspices of a wise and virtuous Administration, proved itself competent to all the objects of national prosperity, comprehended in the views of its framers. No parallel can be found in history, of a transition so rapid as that of the United States from the lowest depression to the highest felicity—from the condition of weak and disjointed republics, to that of a great, united, and prosperous nation.

Although this high state of public happiness has undergone a miserable and afflicting reverse, through the prevalence of a weak and profligate policy, yet the evils and afflictions which have thus been induced upon the country, are not peculiar to any form of Government. The lust and caprice of power, the corruption of patronage, the oppression of the weaker interests of the community by the stronger, heavy taxes, wasteful expenditures, and unjust and ruinous wars, are the natural offspring of bad Administrations, in all ages and countries. It was indeed to be hoped, that the rulers of these States would not make such disastrous haste to involve their infancy in the embarrassments of old and rotten institutions. Yet all this have they done; and their conduct calls loudly for their dismission and disgrace. But to attempt upon every abuse of power to change the Constitution, would be to perpetuate the evils of revolution. . . .

Finally, if the Union be destined to dissolution, by reason of the multiplied abuses of bad administrations, it should, if possible, be the work of peaceable times, and deliberate consent.—Some new form of confederacy should be substituted among those States, which shall intend to maintain a federal relation to each other.—Events may prove that the causes of our calamities are deep and permanent. They may be found to proceed, not merely from the blindness of prejudice, pride of opinion, violence of party spirit, or the confusion of the times; but they may be traced to implacable combinations of individuals, or of States, to monopolize power and office, and to trample without remorse upon the rights and interests of commercial sections of the Union. Whenever it shall appear that these causes are radical and permanent, a separation by equitable arrangement, will be preferable to an alliance by constraint, among nominal friends, but real enemies, inflamed by mutual hatred and jealousy, and inviting by intestine divisions, contempt, and aggression from abroad. But a severance of the Union by one or more States, against the will of the rest, and especially in a time of war, can be justified only by absolute necessity. These are among the principal objections against precipitate measures tending to disunite the States, and when examined in connection with the farewell address of the Father of his country, they must, it is believed, be deemed conclusive. . . .

That acts of Congress in violation of the Constitution are absolutely void, is an undeniable position. It does not, however, consist with the respect and forbearance due from a confederate state towards the General Government, to fly to open resistance upon every infraction of the Constitution. The mode and the energy of the opposition, should always conform to the nature of the violation, the intention of its authors, the extent of the injury inflicted, the determination manifested to persist in it, and the danger of delay. But in cases of deliberate, dangerous, and palpable infractions of the Constitution, affecting the sovereignty of a State, and liberties of the people; it is not only the right but the duty of such a State to interpose its authority for their protection, in the manner best calculated to secure that end. When emergencies occur, which are either beyond the reach of the judicial tribunals, or too pressing to admit of the delay incident to their forms, states, which have no common umpire, must be their own judges, and execute their own decisions. It will thus be proper for the several states to await the ultimate disposal of the obnoxious measures, recommended by the Secretary of War, or pending before Congress, and so to use their power according to the character these measures shall finally assume, as effectually to protect their own sovereignty, and the rights and liberties of their citizens. . . .

The last inquiry, what course of conduct ought to be adopted by the aggrieved states, is in a high degree momentous. When a great and brave people shall feel themselves deserted by their Government, and reduced to the necessity either of submission to a foreign enemy, or of appropriating to their own use, those means of defense which are indispensable to self-preservation, they cannot consent to wait passive spectators of approaching ruin, which it is in their power to avert, and to resign the last remnant of their industrious earnings, to be dissipated in support of measures destructive of the best interests of the nation.

This Convention will not trust themselves to express their conviction of the catastrophe to which such a state of things inevitably tends. Conscious of their high responsibility to God and their country, solicitous for the continuance of the Union, as well as the sovereignty of the states, unwilling to furnish obstacles to peace—resolute never to submit to a foreign enemy, and confiding in the Divine care and protection, they will, until the last hope shall be extinguished, endeavor to avert such consequences. . . .

[T]he duty incumbent on this Convention will not have been performed, without exhibiting some general view of such measures as they deem essential to secure the nation against a relapse into difficulties and dangers, should they, by the blessing of Providence, escape from their present condition, without absolute ruin. . . .

To investigate and explain the means whereby this fatal reverse has been effected, would require a voluminous discussion. Nothing more can be attempted in this Report, than a general allusion to the principal outlines of the policy which has produced this vicissitude. Among these may be enumerated

First.—A deliberate and extensive system for effecting a combination among certain states, by exciting local jealousies and ambition, so as to secure to popular leaders in one section of the Union, the controul of public affairs in perpetual succession. To which primary object most other characteristics of the system may be reconciled.

Secondly.—The political intolerance displayed and avowed, in excluding from office men of unexceptionable merit, for want of adherence to the executive creed.

Thirdly.—The infraction of the judiciary authority and rights, by depriving judges of their offices in violation of the Constitution.

Fourthly.—The abolition of existing taxes, requisite to prepare the Country for those changes to which nations are always exposed, with a view to the acquisition of popular favour.

Fifthly.—The influence of patronage in the distribution of offices, which in these States has been almost invariably made among men the least entitled to such distinction, and who have sold themselves as ready instruments for distracting public opinion, and encouraging administration to hold in contempt the wishes and remonstrances of a people thus apparently divided.

Sixthly.—The admission of new States into the Union, formed at pleasure in the western region, has destroyed the balance of power which existed among the original States, and deeply affected their interest.

Seventhly.—The easy admission of naturalized foreigners, to places of trust, honour or profit, operating as an inducement to the malcontent subjects of the old world to come to these States, in quest of executive patronage, and to repay it by an abject devotion to executive measures.

Eighthly.—Hostility to Great-Britain, and partiality to the late government of France, adopted as coincident with popular prejudice, and subservient to the main object, party power. Connected with these must be ranked erroneous and distorted estimates of the power and resources of those nations, of the probable results of their controversies, and of our political relations to them respectively.

Lastly and principally.—A visionary and superficial theory in regard to commerce, accompanied by a real hatred but a feigned regard to its interests, and a ruinous perseverance in efforts to render it an instrument of coercion and war.

But it is not conceivable that the obliquity of any administration could, in so short a period, have so nearly consummated the work of national ruin, unless favored by defects in the Constitution.

To enumerate all the improvements of which that instrument is susceptible, and to propose such amendments as might render it in all respects perfect, would be a task, which this Convention has not thought proper to assume.—They have confined their attention to such as experience has demonstrated to be essential, and even among these, some are considered entitled to a more serious attention than others. They are suggested without any intentional disrespect to other States, and are meant to be such as all shall find an interest in promoting. Their object is to strengthen, and if possible to perpetuate, the Union of the States, by removing the grounds of existing jealousies, and providing for a fair and equal representation and a limitation of powers, which have been misused.

The first amendment proposed, relates to the apportionment of Representatives among the slave holding States. This cannot be claimed as a right. Those States are entitled to the slave representation, by a constitutional compact. It is therefore merely a subject of agreement, which should be conducted upon principles of mutual interest and accommodation, and upon which no sensibility on either side should be permitted to exist. It has proved unjust and unequal in its operation. . . .

The next amendment relates to the admission of new States into the union.

. . . The object is merely to restrain the constitutional power of Congress in admitting new states. At the adoption of the Constitution, a certain balance of power among the original parties was considered to exist, and there was at that time, and yet is among those parties, a strong affinity between their great and general interests.—By the admission of these States that balance has been materially affected, and unless the practice be modified, must ultimately be destroyed. . . .

The next amendments proposed by the Convention, relate to the powers of Congress, in relation to Embargo and the interdiction of commerce.

Whatever theories upon the subject of commerce, have hitherto divided the opinions of statesmen, experience has at last shewn that it is a vital interest in the United States, and that its success is essential to the encouragement of agriculture and manufactures, and to the wealth, finances, defense, and liberty of the nation. Its welfare can never interfere with the other great interests of the State, but must promote and uphold them. Still those who are immediately concerned in the prosecution of commerce, will of necessity be always a minority of the nation.

. . . [T]hey are entirely unable to protect themselves against the sudden and injudicious decisions of bare majorities, and the mistaken or oppressive projects of those who are not actively concerned in its pursuits. Of consequence, this interest is always exposed to be harassed, interrupted, and entirely destroyed, upon pretense of securing other interests. Had the merchants of this nation been permitted, by their own government, to pursue an innocent and lawful commerce, how different would have been the state of the treasury and of public credit! . . . No union can be durably cemented, in which every great interest does not find itself reasonably secured against the encroachment and combinations of other interests. When, therefore, the past system of embargoes and commercial restrictions shall have been reviewed . . . the reasonableness of some restrictions upon the power of a bare majority to repeat these oppressions, will appear to be obvious.

The next amendment proposes to restrict the power of making offensive war. In the consideration of this amendment, it is not necessary to inquire into the justice of the present war. But one sentiment now exists in relation to its expediency, and regret for its declaration is nearly universal. . . . In this case, as in the former, those more immediately exposed to its fatal effects are a minority of the nation. The commercial towns, the shores of our seas and rivers, contain the population, whose vital interests are most vulnerable by a foreign enemy. Agriculture, indeed, must feel at last, but this appeal to its sensibility comes too late. Again, the immense population which has swarmed into the West, remote from immediate danger, and which is constantly augmenting, will not be averse from [insulated from] the occasional disturbances of the Atlantic States. Thus interest may not unfrequently combine with passion and intrigue, to plunge the nation into needless wars, and compel it to become a military, rather than a happy and flourishing people. These considerations which it would be easy to augment, call loudly for the limitation proposed in the amendment.

Another amendment, subordinate in importance, but still in a high degree expedient, relates to the exclusion of foreigners, hereafter arriving in the United States, from the capacity of holding offices of trust, honour or profit.

. . . [W]hy admit to a participation in the government aliens who were no parties to the compact—who are ignorant of the nature of our institutions, and have no stake in the welfare of the country, but what is recent and transitory? It is surely a privilege sufficient, to admit them after due probation to become citizens, for all but political purposes. . . .

The last amendment respects the limitation of the office of President, to a single constitutional term, and his eligibility from the same state two terms in succession.

Upon this topic, it is superfluous to dilate. The love of power is a principle in the human heart which too often impels to the use of all practicable means to prolong its duration. The office of President has charms and attractions which operate as powerful incentives to this passion. The first and most natural exertion of a vast patronage is directed towards the security of a new election. The interest of the country, the welfare of the people, even honest fame and respect for the opinion of posterity, are secondary considerations. All the engines of intrigue; all the means of corruption, are likely to be employed for this object. A President whose political career is limited to a single election, may find no other interest than will be promoted by making it glorious to himself, and beneficial to his country. But the hope of reelection is prolific of temptations, under which these magnanimous motives are deprived of their principal force. . . .

Such is the general view which this Convention has thought proper to submit, of the situation of these States, of their dangers and their duties. . . . The peculiar difficulty and delicacy of performing, even this undertaking, will be appreciated by all who think seriously upon the crisis. Negotiations for Peace, are at this hour supposed to be pending, the issue of which must be deeply interesting to all. No measures should be adopted, which might unfavorably affect that issue; none which should embarrass the Administration, if their professed desire for peace is sincere; and none, which on supposition of their insincerity, should afford them pretexts for prolonging the war, or relieving themselves from the responsibility of a dishonorable peace. It is also devoutly to be wished, that an occasion may be afforded to all friends of the country, of all parties, and in all places, to pause and consider the awful state to which pernicious counsels, and blind passions, have brought this people. The number of those who perceive, and who are ready to retrace errors, must it is believed be yet sufficient to redeem the nation. It is necessary to rally and unite them by the assurance that no hostility to the Constitution is meditated, and to obtain their aid, in placing it under guardians, who alone can save it from destruction. Should this fortunate change be effected, the hope of happiness and honor may once more dispel the surrounding gloom. Our nation may yet be great, our union durable. But should this prospect be utterly hopeless, the time will not have been lost, which shall have ripened a general sentiment of the necessity of more mighty efforts to rescue from ruin, at least some portion of our beloved Country.

THEREFORE RESOLVED—

. . . Resolved, That the following amendments of the Constitution of the United States, be recommended to the states represented as aforesaid, to be proposed by them for adoption by the State Legislatures, and, in such cases as may be deemed expedient, by a Convention chosen by the people of each State.

And it is further recommended, that the said states shall persevere in their efforts to obtain such amendments, until the same shall be effected.

First. Representatives and direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several states which may be included within this union, according to their respective numbers of free persons, including those bound to serve for a term of years and excluding Indians not taxed, and all other persons.

Second. No new state shall be admitted into the union by Congress in virtue of the power granted by the Constitution, without the concurrence of two thirds of both Houses.

Third. Congress shall not have power to lay any embargo on the ships or vessels of the citizens of the United States, in the ports or harbours thereof, for more than sixty days.

Fourth. Congress shall not have power, without the concurrence of two thirds of both Houses, to interdict the commercial intercourse between the United States and any foreign nation or the dependencies thereof.

Fifth. Congress shall not make or declare war, or authorize acts of hostility against any foreign nation without the concurrence of two thirds of both Houses, except such acts of hostility be in defense of the territories of the United States when actually invaded.

Sixth. No person who shall hereafter be naturalized, shall be eligible as a member of the Senate or House of Representatives of the United States, nor capable of holding any civil office under the authority of the United States.

Seventh. The same person shall not be elected President of the United States a second time; nor shall the President be elected from the same state two terms in succession.

Resolved. That if the application of these States to the government of the United States, recommended in a foregoing Resolution, should be unsuccessful, and peace should not be concluded, and the defense of these States should be neglected, as it has been since the commencement of the war, it will in the opinion of this Convention be expedient for the Legislatures of the several States to appoint Delegates to another Convention, to meet at Boston, in the State of Massachusetts, on the third Thursday of June next, with such powers and instructions as the exigency of a crisis so momentous may require. . . .

- 1. Noah Webster, "Origins of the Hartford Convention in 1814," in A Collection of Papers on Political, Literary, and Moral Subjects (Tappan and Dennett, Boston: 1843), 311-315. Noah Webster (1758–1843) was a lexicographer, educator, writer, and politician.

- 2. The Long Island Sound, a body of water between Connecticut, Rhode Island and Long Island, NY.

- 3. The Massachusetts General Court is the state legislature.

- 4. Document 5.

- 5. William Charles, The Hartford Convention, or Leap or No Leap, etching and aquatint, c. 1814. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-10755.

- 6. "From John Adams to William Plumer, 4 December 1814," Founders Online National Archives, last modified November 25, 2017.

- 7. Latin for foolish fire, a phrase used for the fleeting lights sometimes visible at night over marshy ground; hence, something that is misleading.

- 8. William H. Crawford to Jonathan Fisk, December 8, 1814. 12-08, 1814. Manuscript/Mixed Material, The Thomas Jefferson Papers at the Library of Congress. William H. Crawford (1772–1834) was a U.S. Senator from Georgia, Secretary of War and of the Treasury, Minister to France when he wrote this letter, and a presidential candidate in 1824. Jonathan Fisk (1778–1832) was a senator from New York.

- 9. An influential group of Federalists who resided in Massachusetts.

- 10. Public Documents, Containing Proceedings of the Hartford Convention of Delegates…(Massachusetts Senate: 1815), 3-22.

Letter from John Adams to William Plumer (1814)

December 04, 1814

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.