No related resources

Introduction

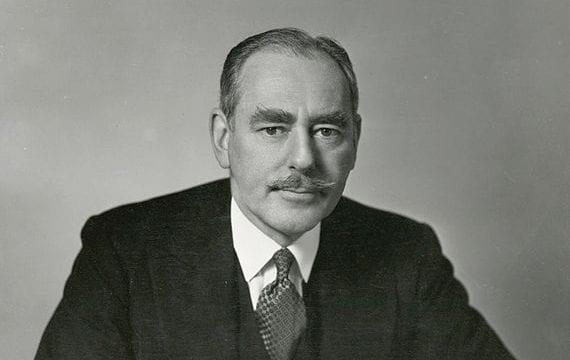

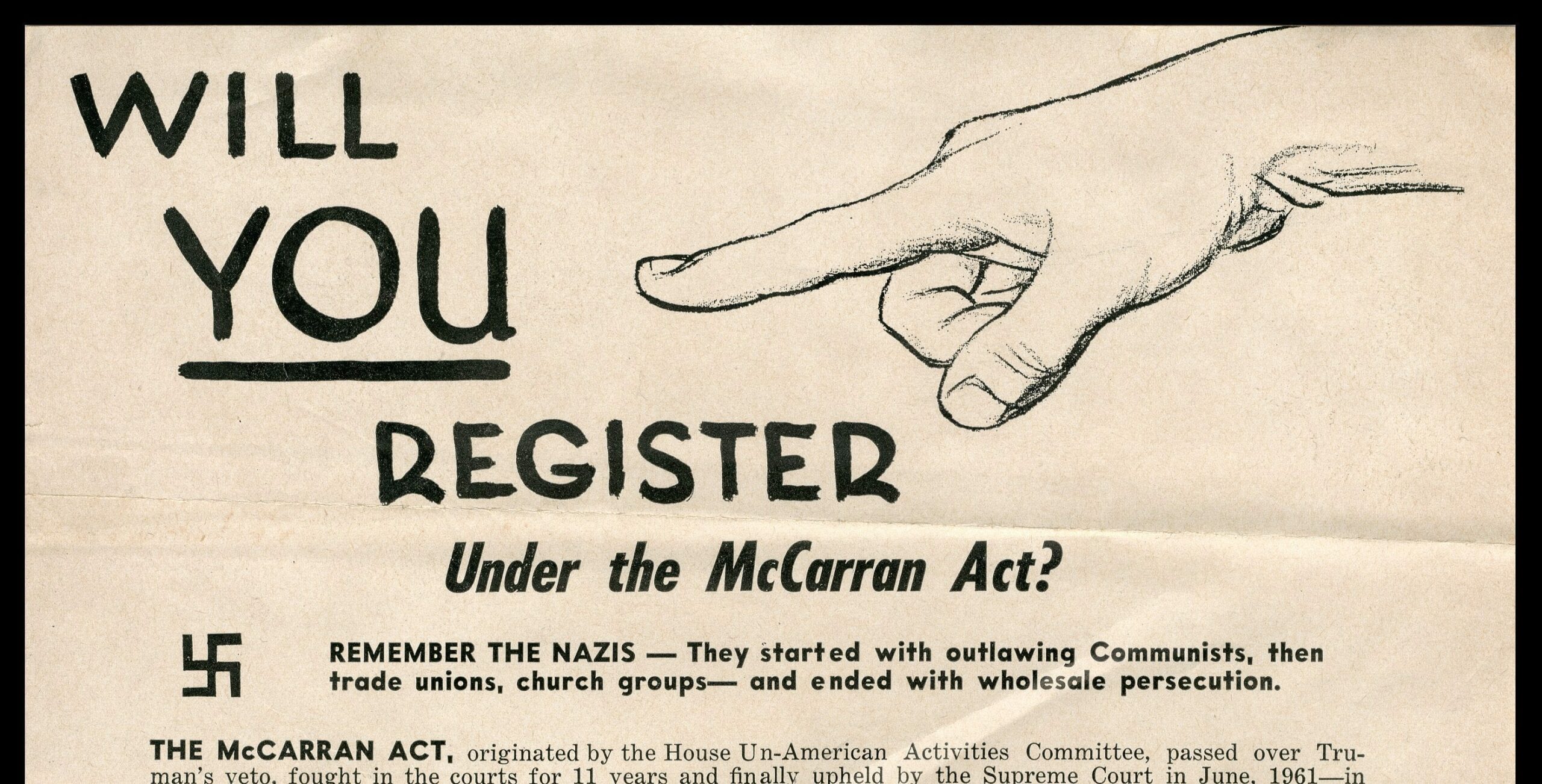

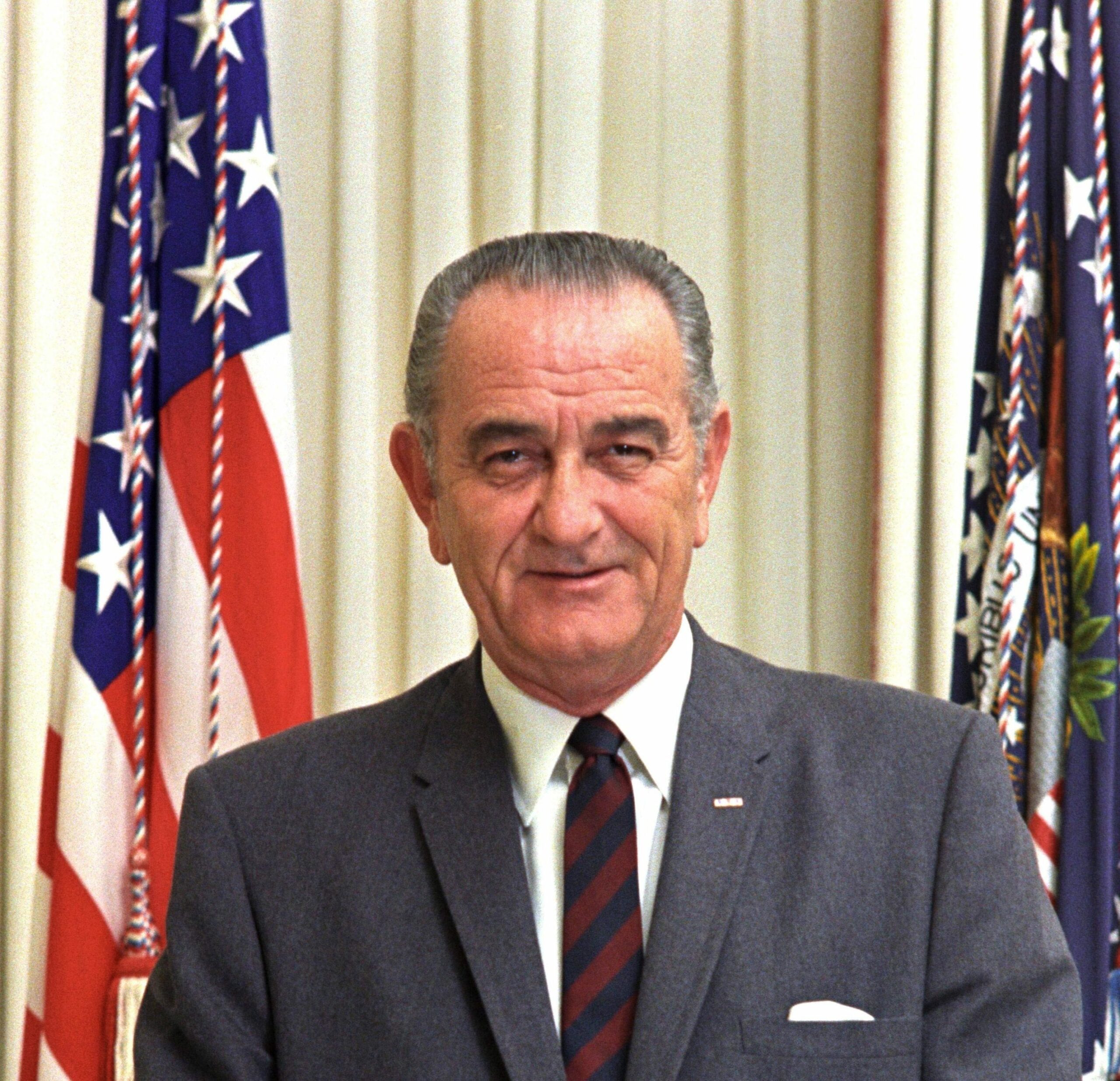

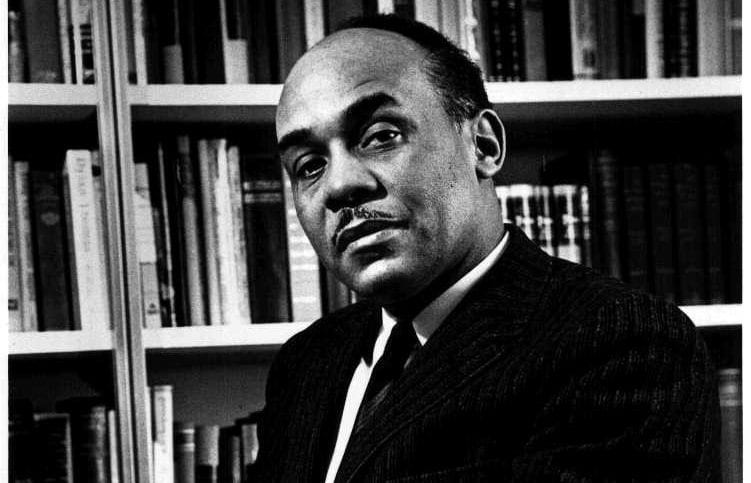

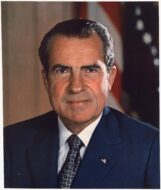

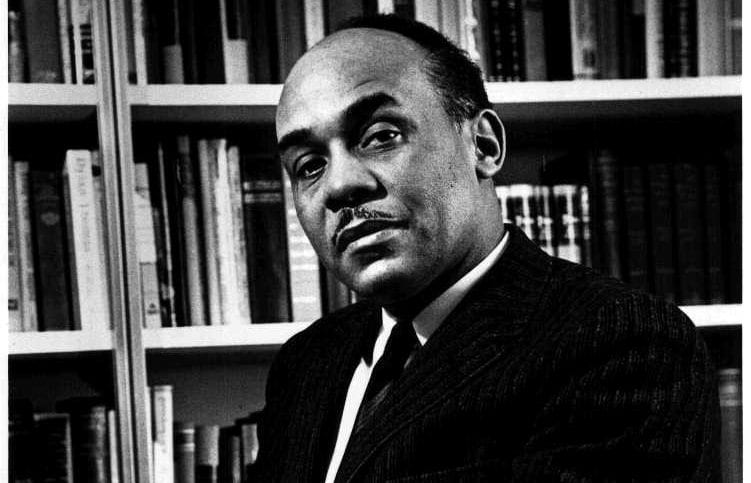

During the Watergate scandal, Richard Nixon refused to answer a subpoena for tapes he had recorded of discussions in the White House and ordered his attorney general, Elliot Richardson (1920–1999), to fire Archibald Cox (1912–2004), the special counsel investigating Watergate. Richardson refused to comply and then resigned his position, as did his successor, William Ruckelshaus (1932–2019). Cox was finally fired by Nixon’s solicitor general, Robert Bork (1927–2012). Known as the “Saturday Night Massacre,” the event illustrated the problem of having the executive branch in charge of investigating the misconduct of its own high-ranking officers. Short of impeachment there was simply no means by which such officers could be held accountable. Consequently, Congress passed the Ethics in Government Act in 1978, which provided for the appointment of an “independent” counsel to investigate and prosecute crimes by high-ranking members of the executive branch. Unlike “the special counsel,” the independent counsel could not be removed by the attorney general (except within a narrow set of circumstances).

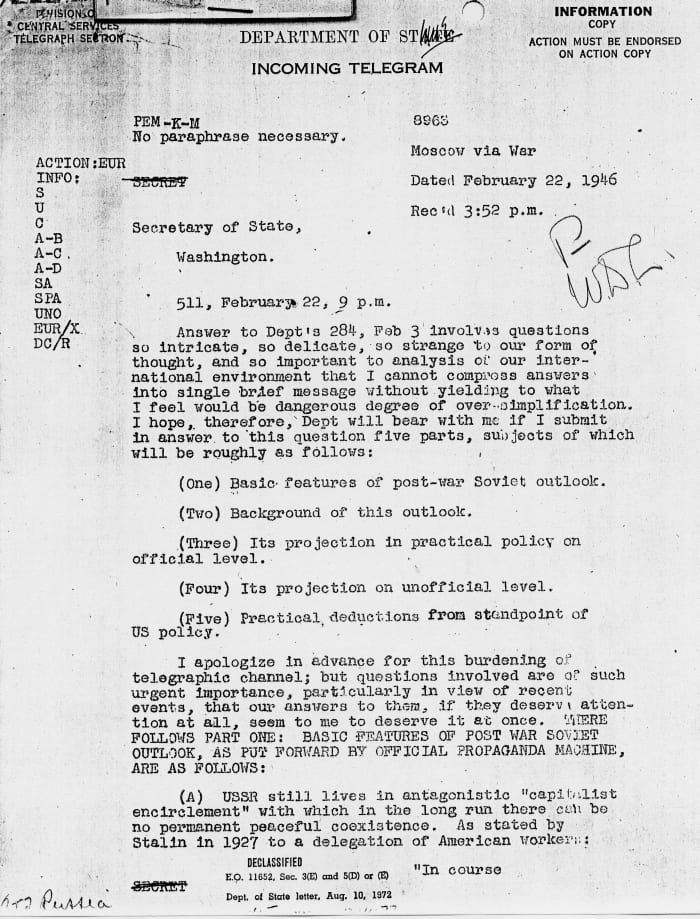

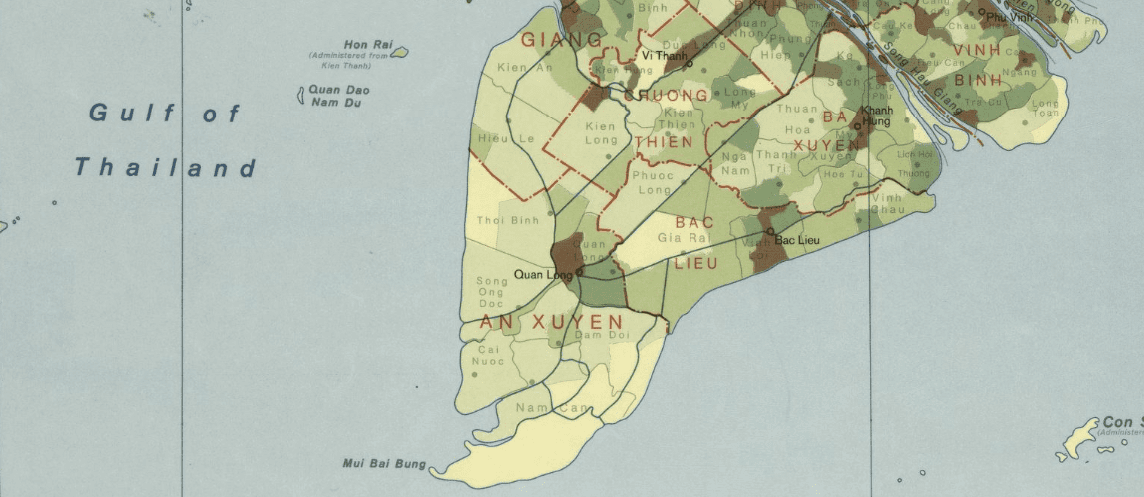

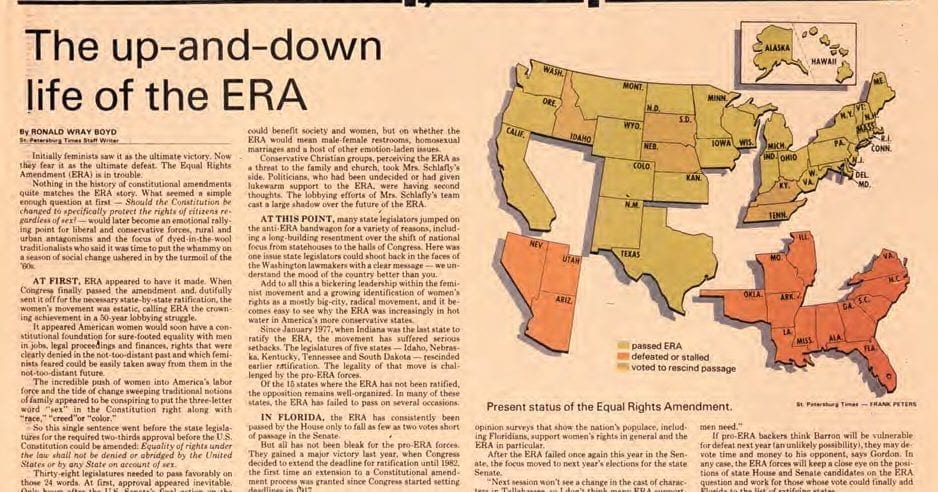

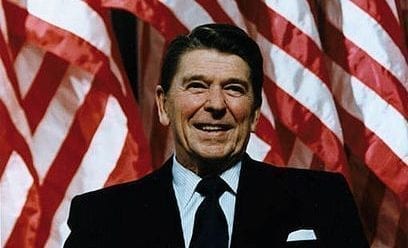

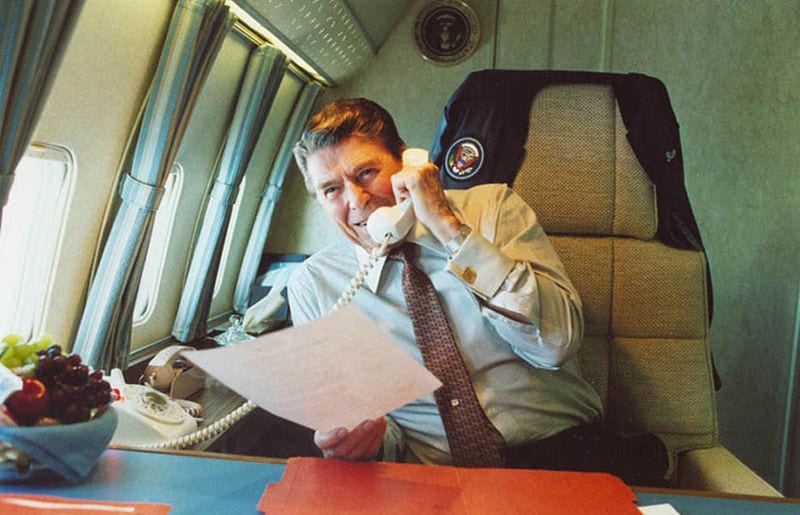

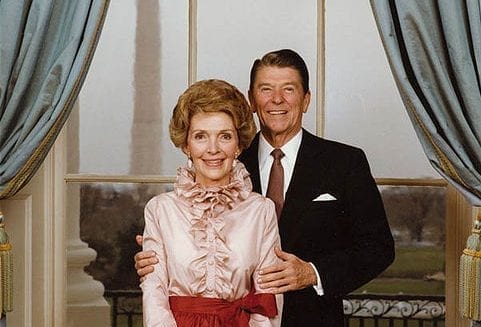

The controversy in Morrison v. Olson arose out of a congressional investigation of the Environmental Protection Agency’s enforcement of the “Superfund Law” under the presidency of Ronald Reagan. Convinced that Reagan’s solicitor general, Theodore Olson (1940–), had withheld documents from a House investigation, the House Judiciary Committee requested the attorney general to appoint an independent counsel to investigate. Alexia Morrison was appointed independent counsel by a Special Division of the Court (a group of three circuit court judges appointed by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court) under the procedures established by the independent counsel statute of the Ethics in Government Act. When Morrison caused a grand jury to issue a subpoena, Olson moved to quash the subpoena on the grounds that the independent counsel provision of the law was unconstitutional.

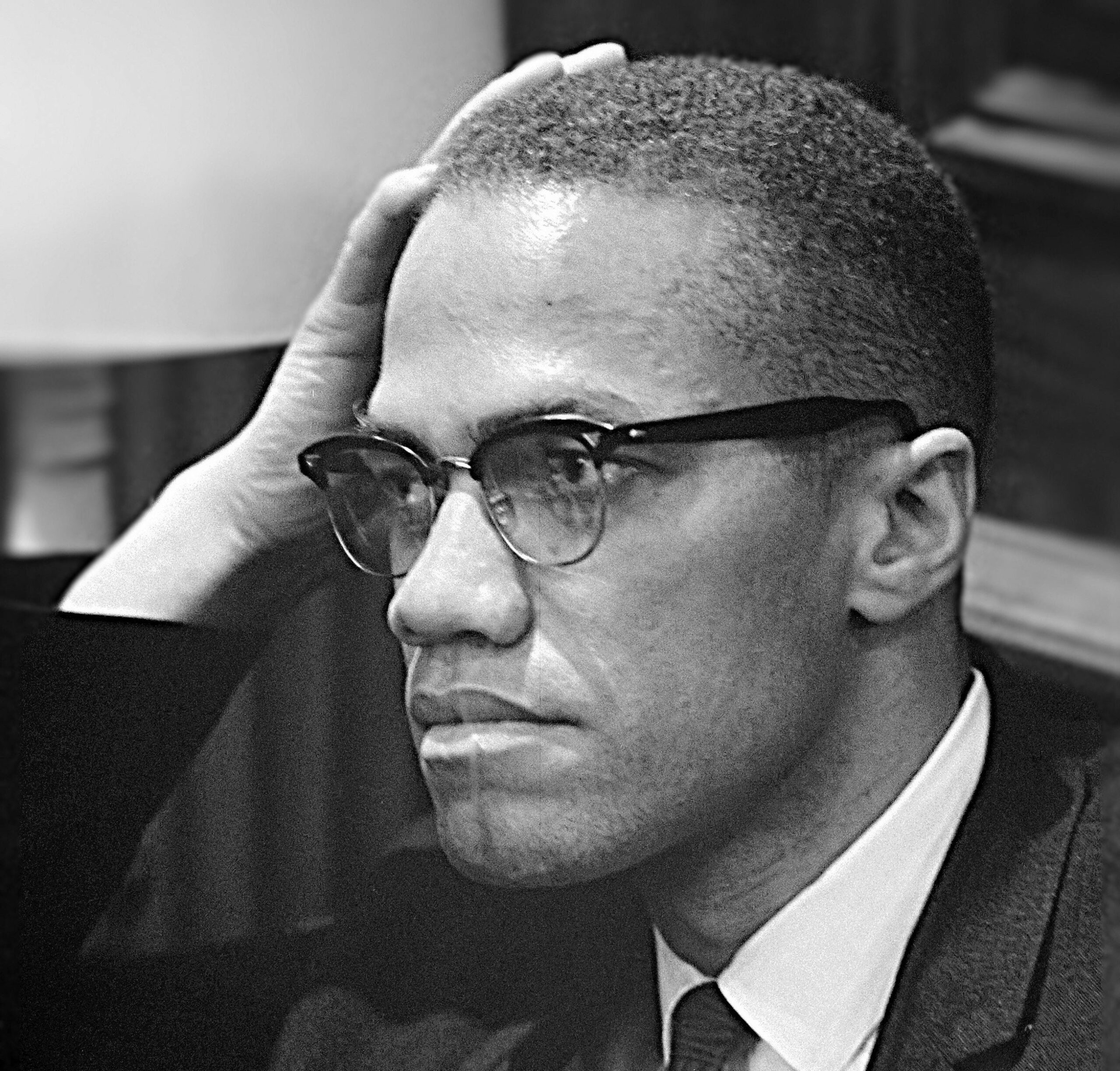

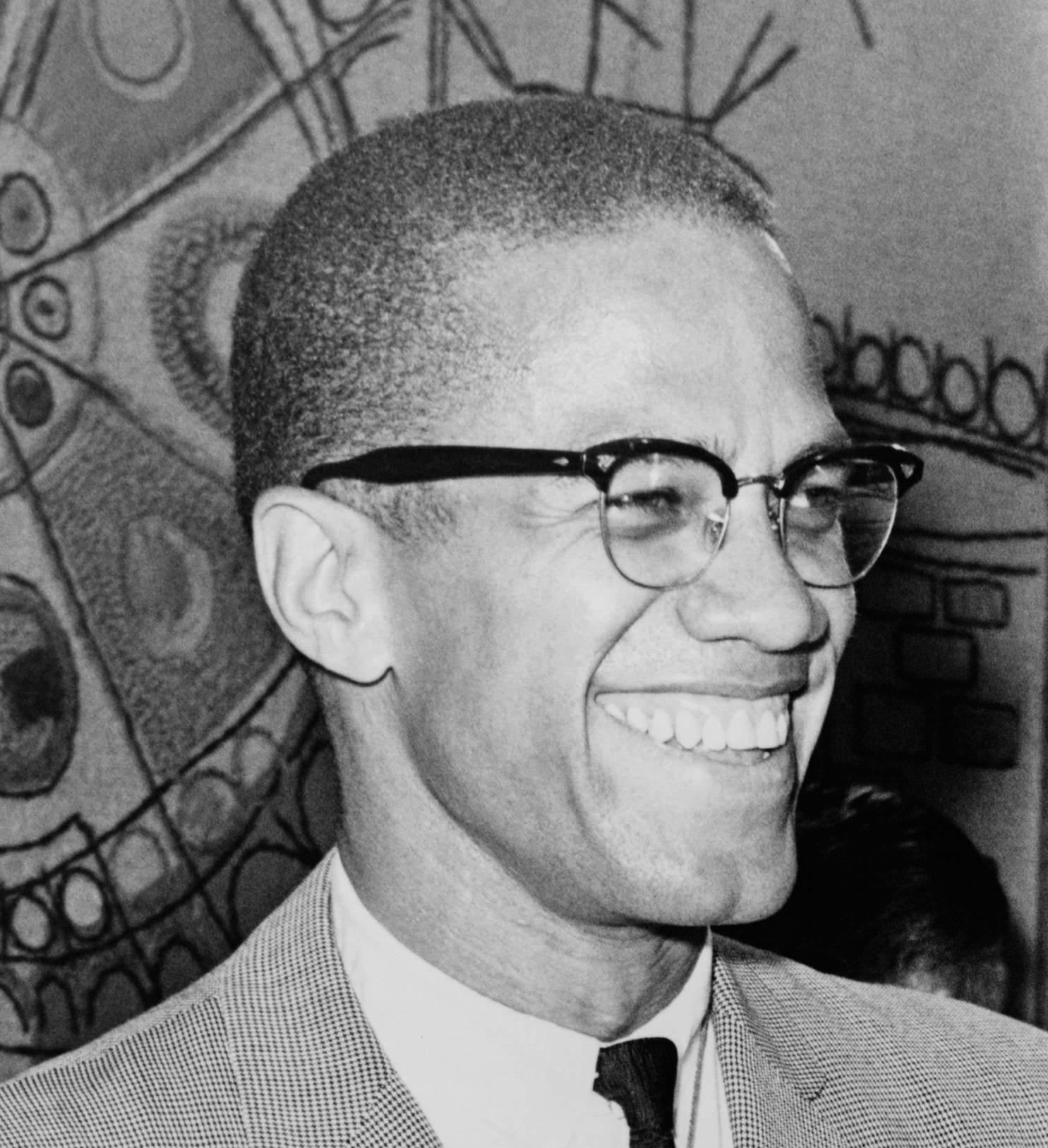

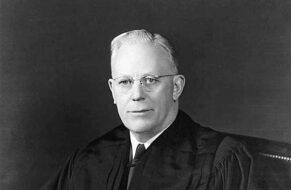

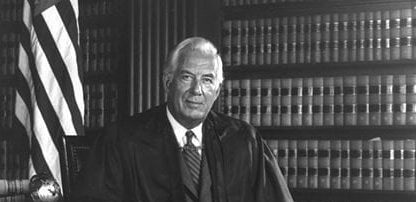

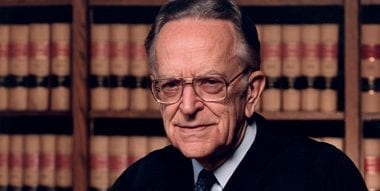

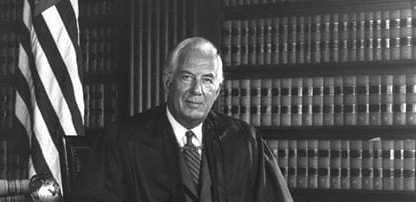

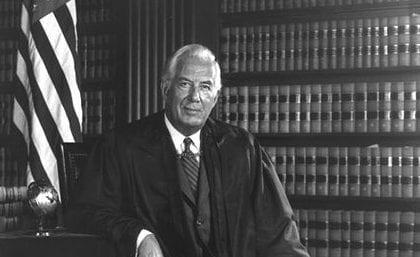

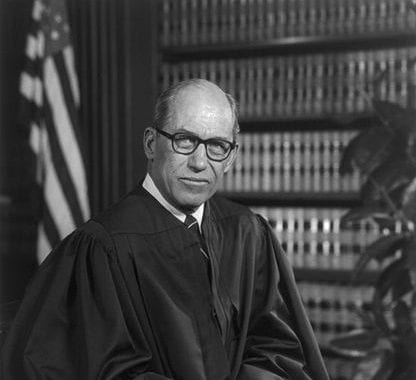

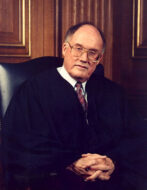

The opinion by Chief Justice Rehnquist (1924–2005) and the dissent by Justice Scalia (1936–2016) in this case (the Court split 7–1) illustrate competing views on the meaning of the separation of powers and how that scheme ought to be understood in the light of the challenges of modern governance. Rehnquist’s majority opinion argued for a more flexible approach to separation of powers in which Congress could legislate additional checks on a powerful executive to ensure accountability. Scalia, by contrast, argued that any departure from the formal division of powers not only violated the Constitution but would have detrimental consequences for the separation of powers in practice.

487 U.S. 654 (1988), https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/487/654/.

Chief Justice Rehnquist delivered the opinion of the Court.

We now turn to consider whether the act is invalid under the constitutional principle of separation of powers. Two related issues must be addressed: The first is whether the provision of the act restricting the attorney general’s power to remove the independent counsel to only those instances in which he can show “good cause,” taken by itself, impermissibly interferes with the president’s exercise of his constitutionally appointed functions. The second is whether, taken as a whole, the act violates the separation of powers by reducing the president’s ability to control the prosecutorial powers wielded by the independent counsel.

. . .Contrary to the implication of some dicta in Myers,1 the president’s power to remove government officials simply was not “all-inclusive in respect of civil officers with the exception of the judiciary provided for by the Constitution.”2 At least in regard to “quasi-legislative” and “quasi-judicial” agencies such as the FTC [Federal Trade Commission], “[t]he authority of Congress, in creating [such] agencies, to require them to act in discharge of their duties independently of executive control . . . includes, as an appropriate incident, power to fix the period during which they shall continue in office, and to forbid their removal except for cause in the meantime.”3 In Humphrey’s Executor,4 we found it “plain” that the Constitution did not give the president “illimitable power of removal” over the officers of independent agencies. Were the president to have the power to remove FTC commissioners at will, the “coercive influence” of the removal power would “threate[n] the independence of [the] commission.”

Appellees contend that Humphrey’s Executor. . .[is] distinguishable from this case because [it] did not involve officials who performed a “core executive function.” They argue that our decision in Humphrey’s Executor rests on a distinction between “purely executive” officials and officials who exercise “quasi-legislative” and “quasi-judicial” powers. In their view, when a “purely executive” official is involved, the governing precedent is Myers, not Humphrey’s Executor.. . .

We undoubtedly did rely on the terms “quasi-legislative” and “quasijudicial” to distinguish the officials involved in Humphrey’s Executor… from those in Myers, but our present considered view is that the determination of whether the Constitution allows Congress to impose a “good cause”–type restriction on the president’s power to remove an official cannot be made to turn on whether or not that official is classified as “purely executive.” The analysis contained in our removal cases is designed not to define rigid categories of those officials who may or may not be removed at will by the president, but to ensure that Congress does not interfere with the president’s exercise of the “executive power” and his constitutionally appointed duty to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed” under Article II. Myers was undoubtedly correct in its holding, and in its broader suggestion that there are some “purely executive” officials who must be removable by the president at will if he is to be able to accomplish his constitutional role. . . . But the real question is whether the removal restrictions are of such a nature that they impede the president’s ability to perform his constitutional duty, and the functions of the officials in question must be analyzed in that light.

Considering for the moment the “good cause” removal provision in isolation from the other parts of the act at issue in this case, we cannot say that the imposition of a “good cause” standard for removal by itself unduly trammels on executive authority. . . .Although the counsel exercises no small amount of discretion and judgment in deciding how to carry out his or her duties under the act, we simply do not see how the president’s need to control the exercise of that discretion is so central to the functioning of the executive branch as to require as a matter of constitutional law that the counsel be terminable at will by the president. . . .

The final question to be addressed is whether the act, taken as a whole, violates the principle of separation of powers by unduly interfering with the role of the executive branch. . . . We have not hesitated to invalidate provisions of law which violate this principle. On the other hand, we have never held that the Constitution requires that the three branches of government “operate with absolute independence.”. . .

We observe first that this case does not involve an attempt by Congress to increase its own powers at the expense of the executive branch. . . .

Similarly, we do not think that the act works any judicial usurpation of properly executive functions. As should be apparent from our discussion of the Appointments Clause above, the power to appoint inferior officers such as independent counsel is not in itself an “executive” function in the constitutional sense, at least when Congress has exercised its power to vest the appointment of an inferior office in the “courts of law.”. . .

Finally, we do not think that the act “impermissibly undermine[s]” the powers of the executive branch, or “disrupts the proper balance between the coordinate branches [by] prevent[ing] the executive branch from accomplishing its constitutionally assigned functions.”5 It is undeniable that the act reduces the amount of control or supervision that the attorney general and, through him, the president exercises over the investigation and prosecution of a certain class of alleged criminal activity. . . . Nonetheless, the Act does give the Attorney General several means of supervising or controlling the prosecutorial powers that may be wielded by an independent counsel. . . .

In sum, we conclude today that it does not violate the Appointments Clause for Congress to vest the appointment of independent counsel in the Special Division; that the powers exercised by the Special Division under the act do not violate Article III; and that the act does not violate the separation-of-powers principle by impermissibly interfering with the functions of the executive branch. . . .

Justice Scalia, dissenting.

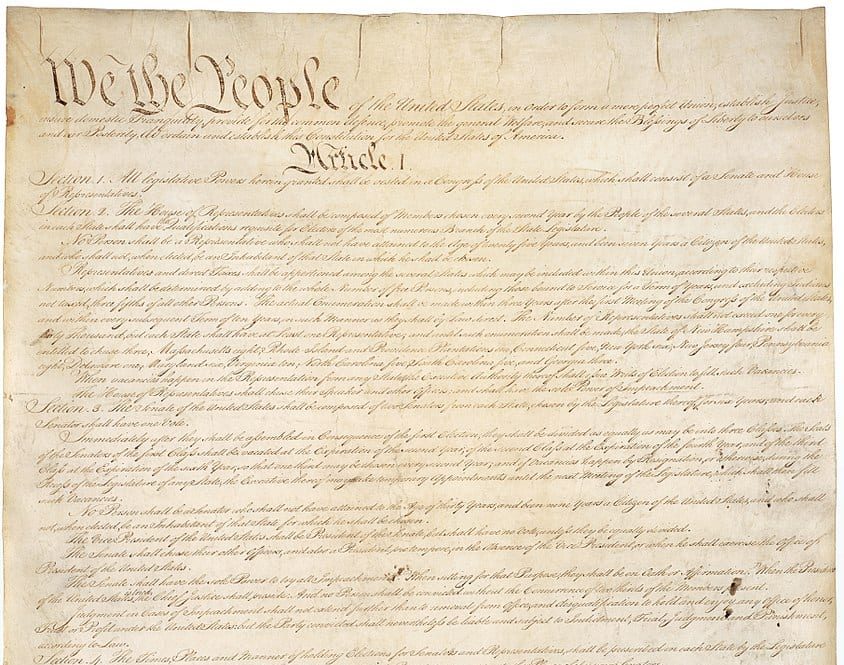

It is the proud boast of our democracy that we have “a government of laws and not of men.”. . .The Framers of the federal Constitution . . . viewed the principle of separation of powers as the absolutely central guarantee of a just government. In No. 47 of The Federalist, Madison wrote that “[n]o political truth is certainly of greater intrinsic value, or is stamped with the authority of more enlightened patrons of liberty.” Without a secure structure of separated powers, our Bill of Rights would be worthless, as are the bills of rights of many nations of the world that have adopted, or even improved upon, the mere words of ours.

The principle of separation of powers is expressed in our Constitution in the first section of each of the first three articles. Article I, 1, provides that “[a]ll legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.” Article III, 1, provides that “[t]he judicial power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.” And the provision at issue here, Art. II, 1, cl. 1, provides that “[t]he executive power shall be vested in a president of the United States of America.”

But just as the mere words of a Bill of Rights are not self-effectuating, the Framers recognized “[t]he insufficiency of a mere parchment delineation of the boundaries” to achieve the separation of powers. . . .

That is what this suit is about. Power. The allocation of power among Congress, the president, and the courts in such fashion as to preserve the equilibrium the Constitution sought to establish—so that “a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department” can effectively be resisted. Frequently an issue of this sort will come before the Court clad, so to speak, in sheep’s clothing: the potential of the asserted principle to effect important change in the equilibrium of power is not immediately evident, and must be discerned by a careful and perceptive analysis. But this wolf comes as a wolf. . . .

If to describe this case is not to decide it, the concept of a government of separate and coordinate powers no longer has meaning. . . .

. . . It seems to me, therefore, that the decision of the Court of Appeals invalidating the present statute must be upheld on fundamental separation-of-powers principles if the following two questions are answered affirmatively: (1) Is the conduct of a criminal prosecution (and of an investigation to decide whether to prosecute) the exercise of purely executive power? (2) Does the statute deprive the president of the United States of exclusive control over the exercise of that power? Surprising to say, the Court appears to concede an affirmative answer to both questions, but seeks to avoid the inevitable conclusion that since the statute vests some purely executive power in a person who is not the president of the United States it is void. . . .

. . .It effects a revolution in our constitutional jurisprudence for the Court, once it has determined that (1) purely executive functions are at issue here, and (2) those functions have been given to a person whose actions are not fully within the supervision and control of the president, nonetheless to proceed further to sit in judgment of whether “the president’s need to control the exercise of [the independent counsel’s] discretion is so central to the functioning of the executive branch” as to require complete control, whether the conferral of his powers upon someone else “sufficiently deprives the president of control over the independent counsel to interfere impermissibly with [his] constitutional obligation to ensure the faithful execution of the laws,” and whether “the act give[s] the executive branch sufficient control over the independent counsel to ensure that the president is able to perform his constitutionally assigned duties.” It is not for us to determine, and we have never presumed to determine, how much of the purely executive powers of government must be within the full control of the president. The Constitution prescribes that they all are.

The utter incompatibility of the Court’s approach with our constitutional traditions can be made more clear, perhaps, by applying it to the powers of the other two branches. Is it conceivable that if Congress passed a statute depriving itself of less than full and entire control over some insignificant area of legislation, we would inquire whether the matter was “so central to the functioning of the legislative branch” as really to require complete control, or whether the statute gives Congress “sufficient control over the surrogate legislator to ensure that Congress is able to perform its constitutionally assigned duties”? Of course we would have none of that. Once we determined that a purely legislative power was at issue we would require it to be exercised, wholly and entirely, by Congress. Or to bring the point closer to home, consider a statute giving to non–Article III judges just a tiny bit of purely judicial power in a relatively insignificant field, with substantial control, though not total control, in the courts. . . .Is there any doubt that we would not pause to inquire whether the matter was “so central to the functioning of the Judicial Branch” as really to require complete control, or whether we retained “sufficient control over the matters to be decided that we are able to perform our constitutionally assigned duties”? . . .

Is it unthinkable that the president should have such exclusive power, even when alleged crimes by him or his close associates are at issue? No more so than that Congress should have the exclusive power of legislation, even when what is at issue is its own exemption from the burdens of certain laws. . . .A system of separate and coordinate powers necessarily involves an acceptance of exclusive power that can theoretically be abused. As we reiterate this very day, “[i]t is a truism that constitutional protections have costs.” While the separation of powers may prevent us from righting every wrong, it does so in order to ensure that we do not lose liberty. . . .

The Court has, nonetheless, replaced the clear constitutional prescription that the executive power belongs to the president with a “balancing test.” What are the standards to determine how the balance is to be struck, that is, how much removal of presidential power is too much? Many countries of the world get along with an executive that is much weaker than ours—in fact, entirely dependent upon the continued support of the legislature. Once we depart from the text of the Constitution, just where short of that do we stop? The most amazing feature of the Court’s opinion is that it does not even purport to give an answer. . . .This is not only not the government of laws that the Constitution established; it is not a government of laws at all. . . .•••The notion that every violation of law should be prosecuted, including—indeed, especially—every violation by those in high places, is an attractive one, and it would be risky to argue in an election campaign that that is not an absolutely overriding value. . . .

. . .A government of laws means a government of rules. Today’s decision on the basic issue of fragmentation of executive power is ungoverned by rule, and hence ungoverned by law. . . .

The ad hoc approach to constitutional adjudication has real attraction, even apart from its work-saving potential. It is guaranteed to produce a result, in every case, that will make a majority of the Court happy with the law. The law is, by definition, precisely what the majority thinks, taking all things into account, it ought to be. I prefer to rely upon the judgment of the wise men who constructed our system, and of the people who approved it, and of two centuries of history that have shown it to be sound. Like it or not, that judgment says, quite plainly, that “[t]he executive power shall be vested in a president of the United States.”

- 1. “Dicta,” or obiter dicta, are comments in a judicial opinion that are incidental to the matter being adjudicated and do not set precedent. Click here for Myers.

- 2. Chief Justice Rehnquist’s note: 295 U.S. at 295 U.S. 629.

- 3. Chief Justice Rehnquist’s note: 295 U.S. at 295 U.S. 629.

- 4. See Report of the President's committee on Administrative Management

- 5. Chief Justice Rehnquist’s note: Nixon v. Administrator of General Services, supra, at 433 U.S. 433.

Originalism: The Lesser Evil

September 16, 1988

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.