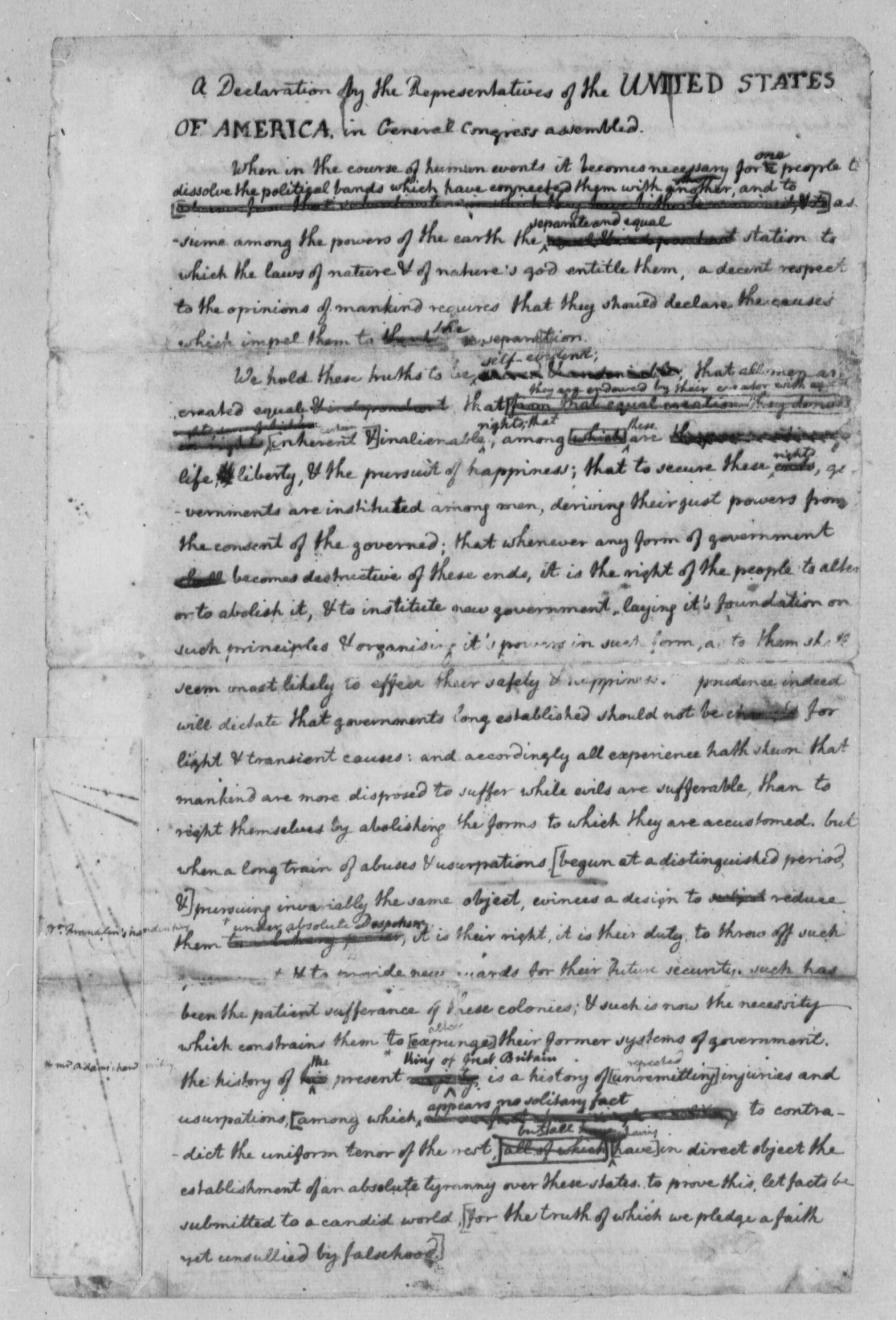

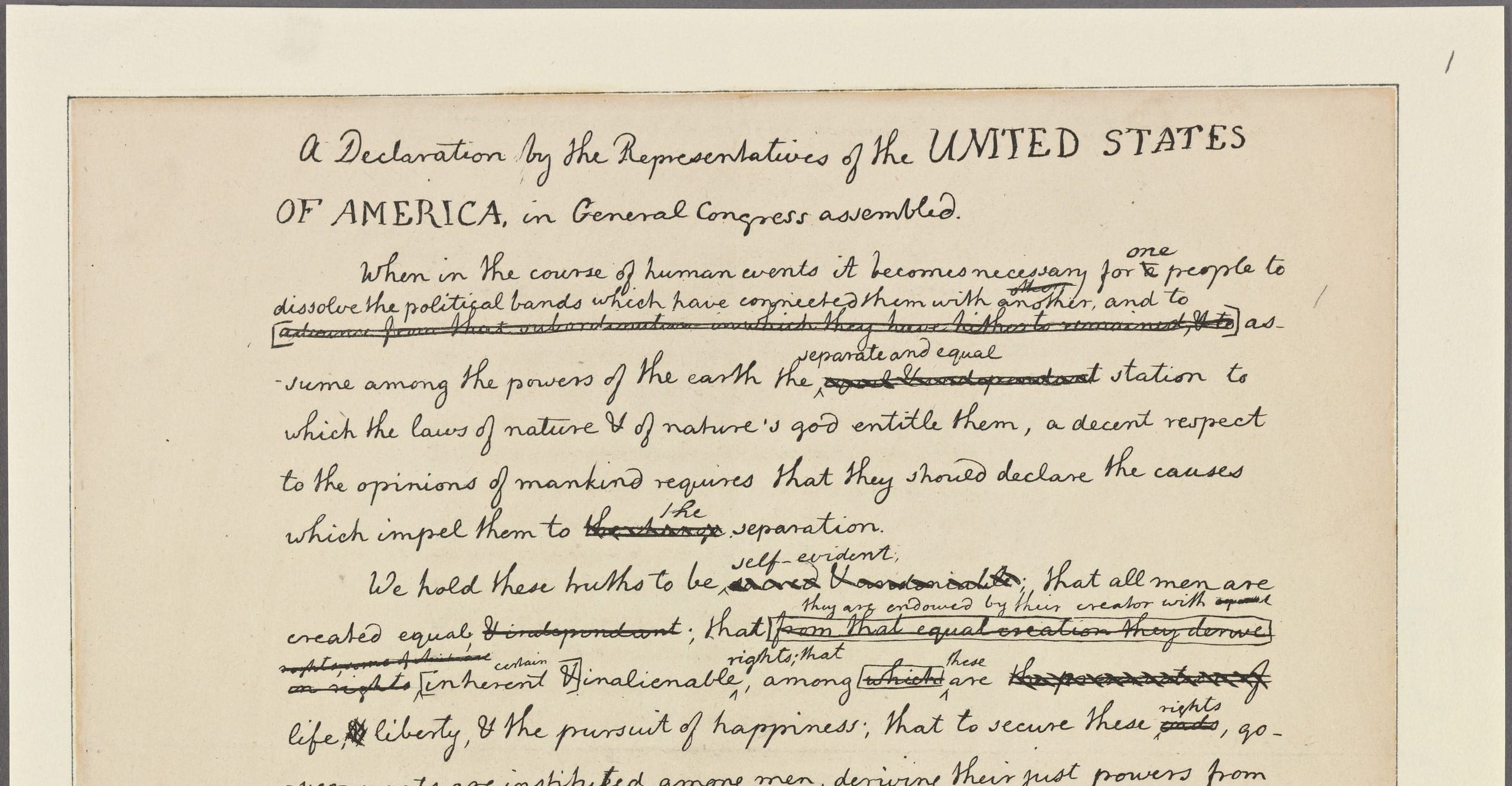

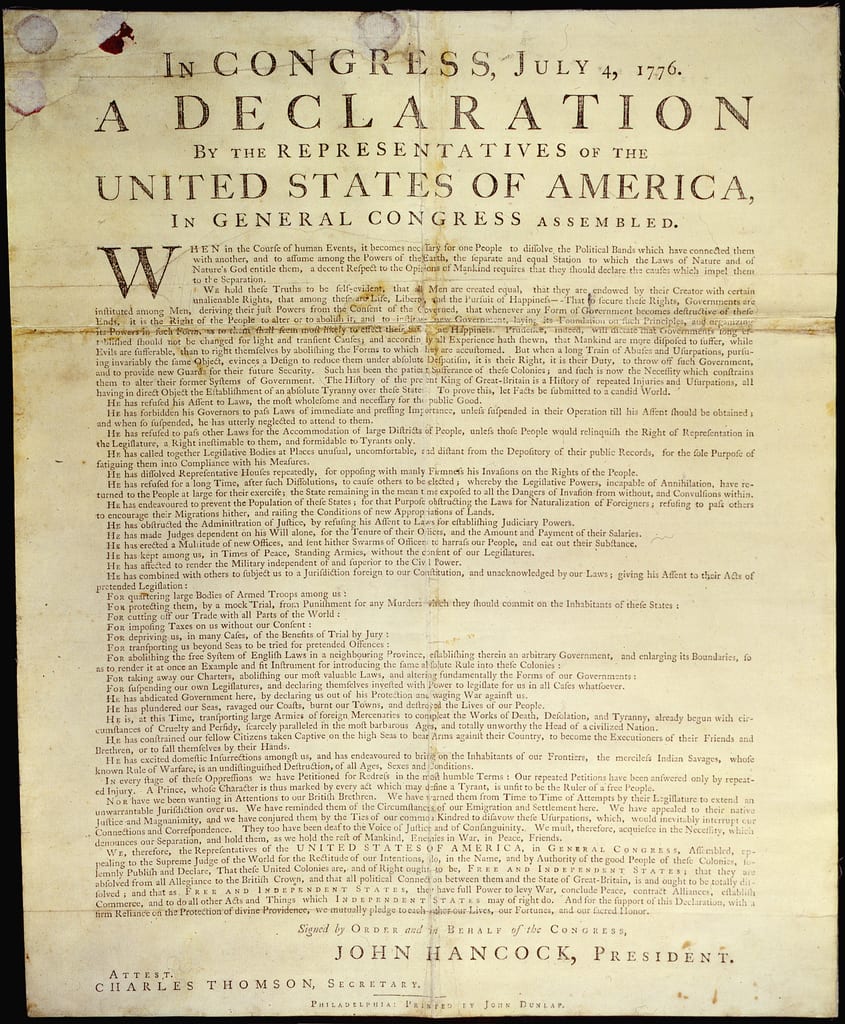

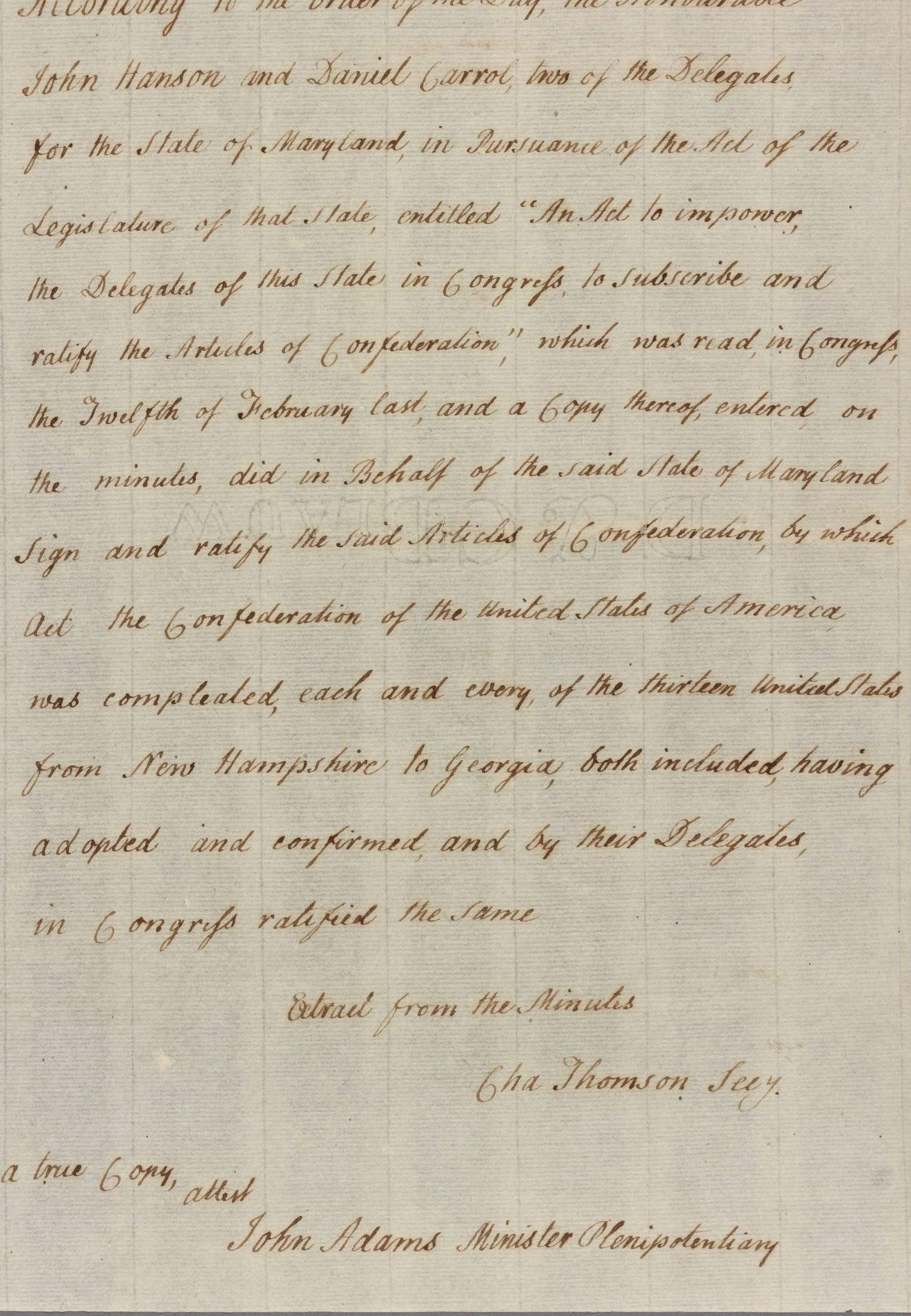

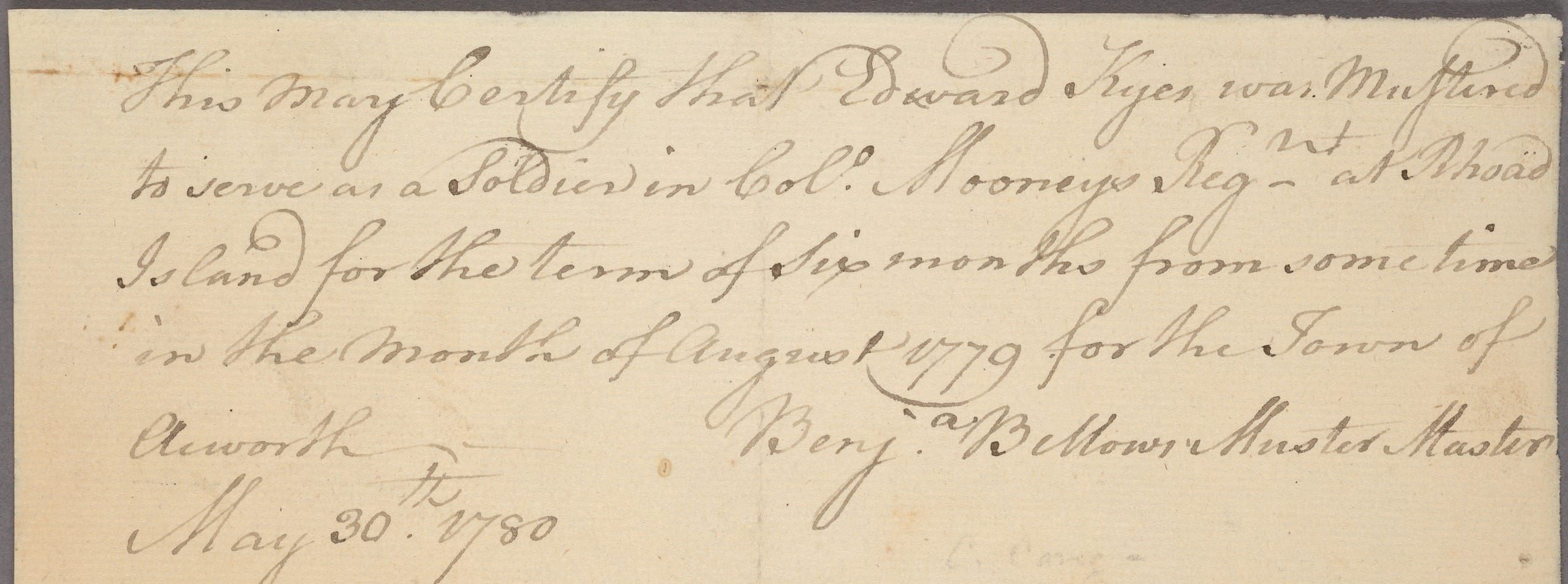

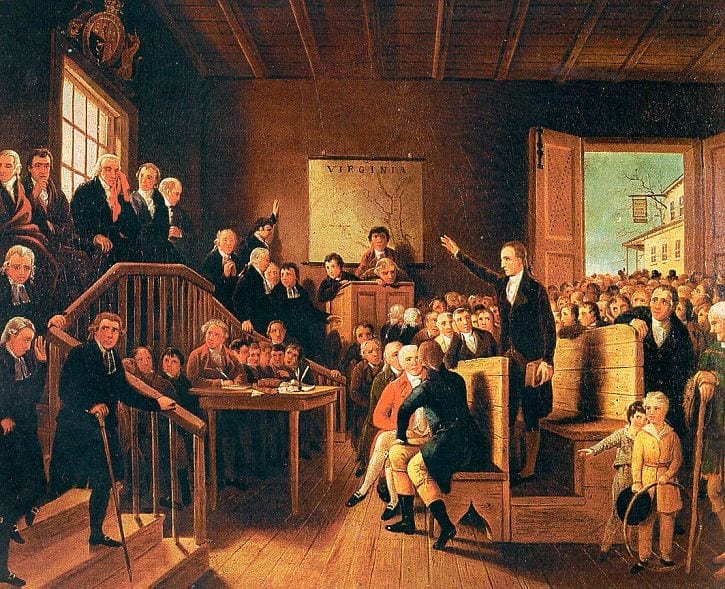

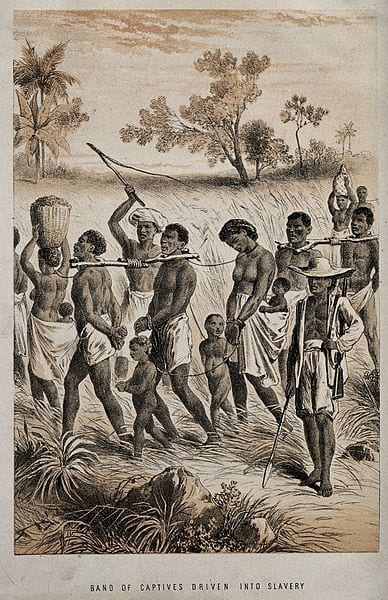

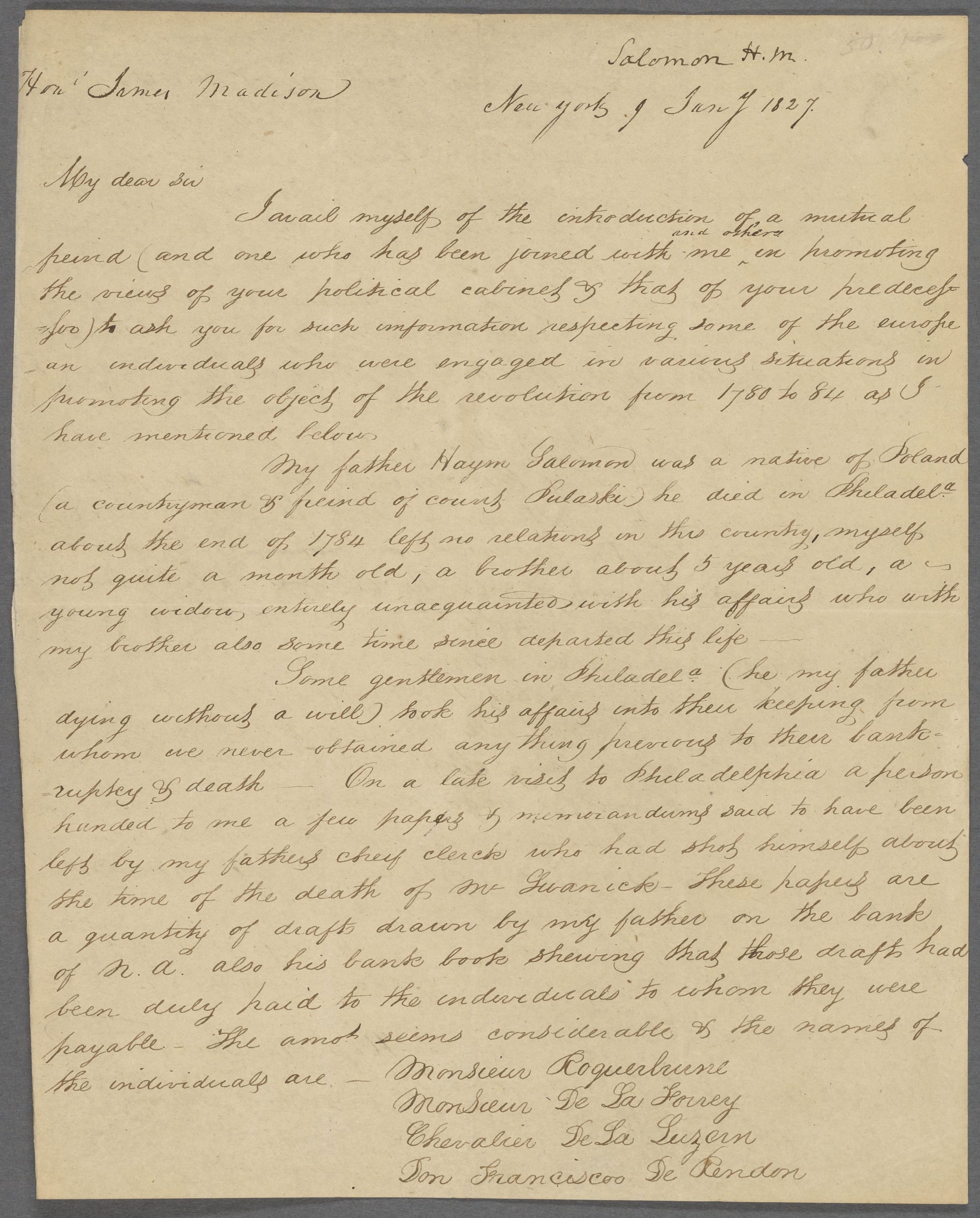

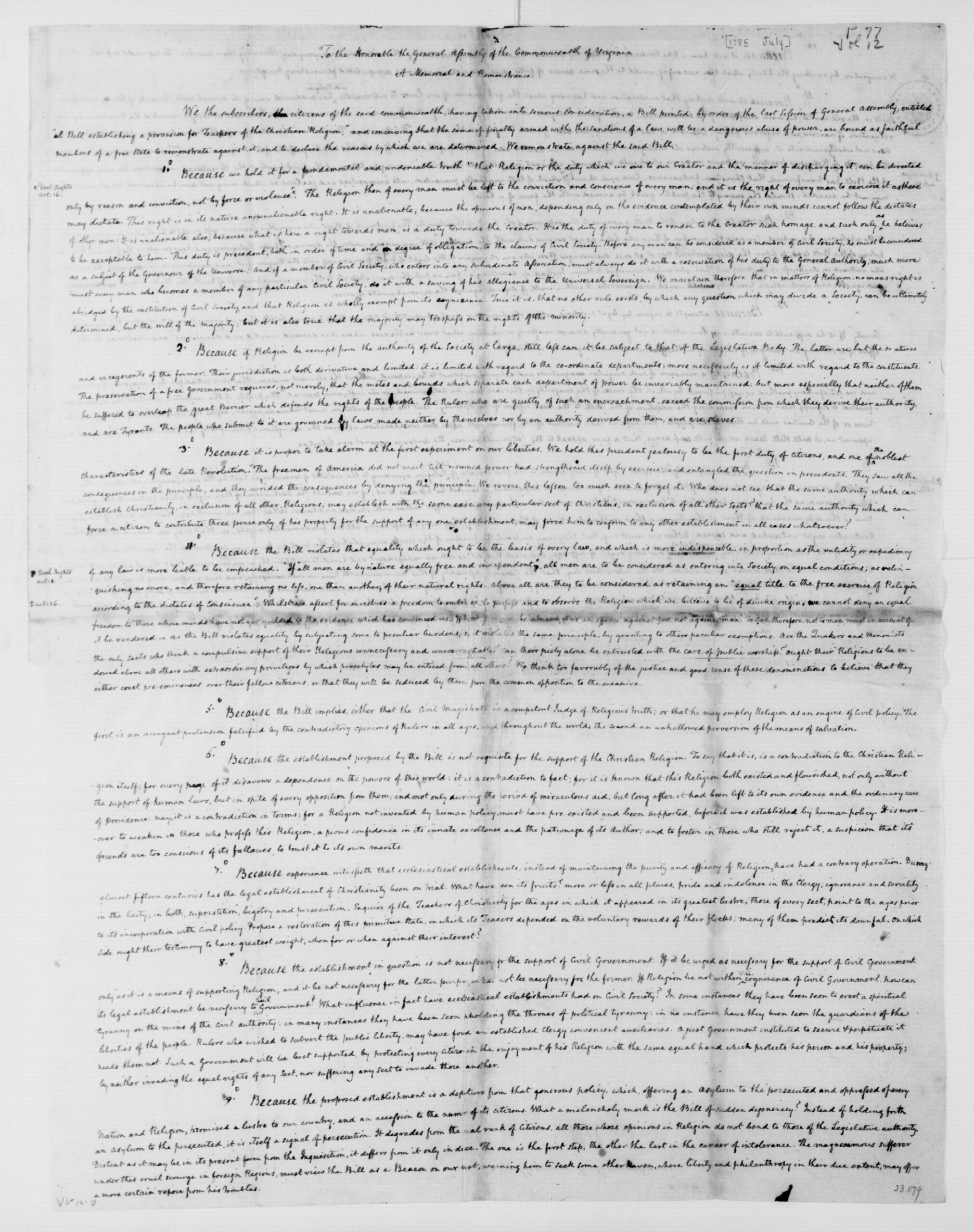

The ideas of the American Revolution could not be contained—a fact made clear by this 1777 petition signed by Prince Hall (ca. 1735–1807), a free black man, and seven other African Americans on behalf of people in Massachusetts who remained enslaved. Hall’s appeal made clear his awareness of the central tenets of the Declaration of Independence (1776): it was sent to the state’s legislature less than six months after the Declaration insisted that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights,” and that “to secure these rights, governments are instituted by men.” Like others in the new country who adopted the freedom argument of the Declaration, Africans made themselves Americans in doing so. Repeatedly, in the decades to come, African Americans would appeal to the principles of the Declaration (“What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” (1852); “Birmingham Manifesto” (1963); Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech (1963).

Although the Massachusetts legislature ignored the petition, the inconsistency between slavery and America’s founding principles did not go unnoticed. Vermont abolished slavery in its 1777 constitution, while New Hampshire’s 1783 frame of government-which declared that “all men are born equal and independent” with natural rights to the enjoyment and defense of “life and liberty”-preceded a decline in slavery so steep that in 1800 only eight slaves were counted in the census. Meanwhile, a 1783 court case ended slavery in Massachusetts. Pennsylvania adopted a gradual emancipation law in 1780, as did Connecticut and Rhode Island in 1784, New York in 1799, and New Jersey in 1804.

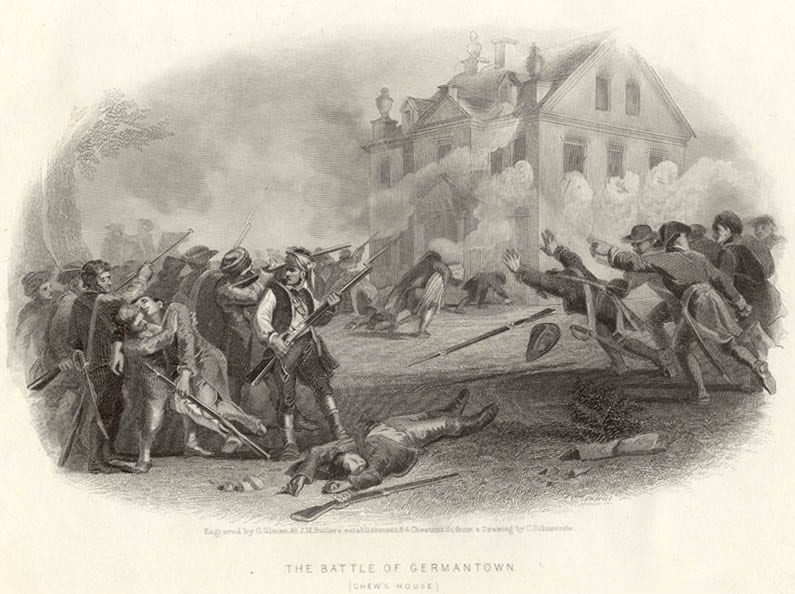

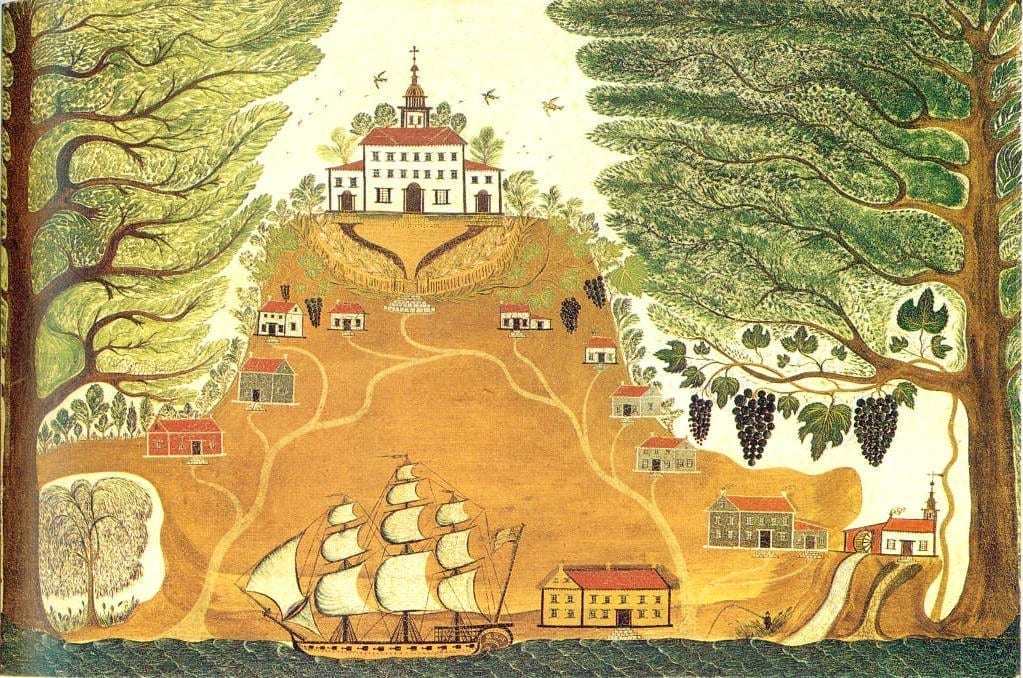

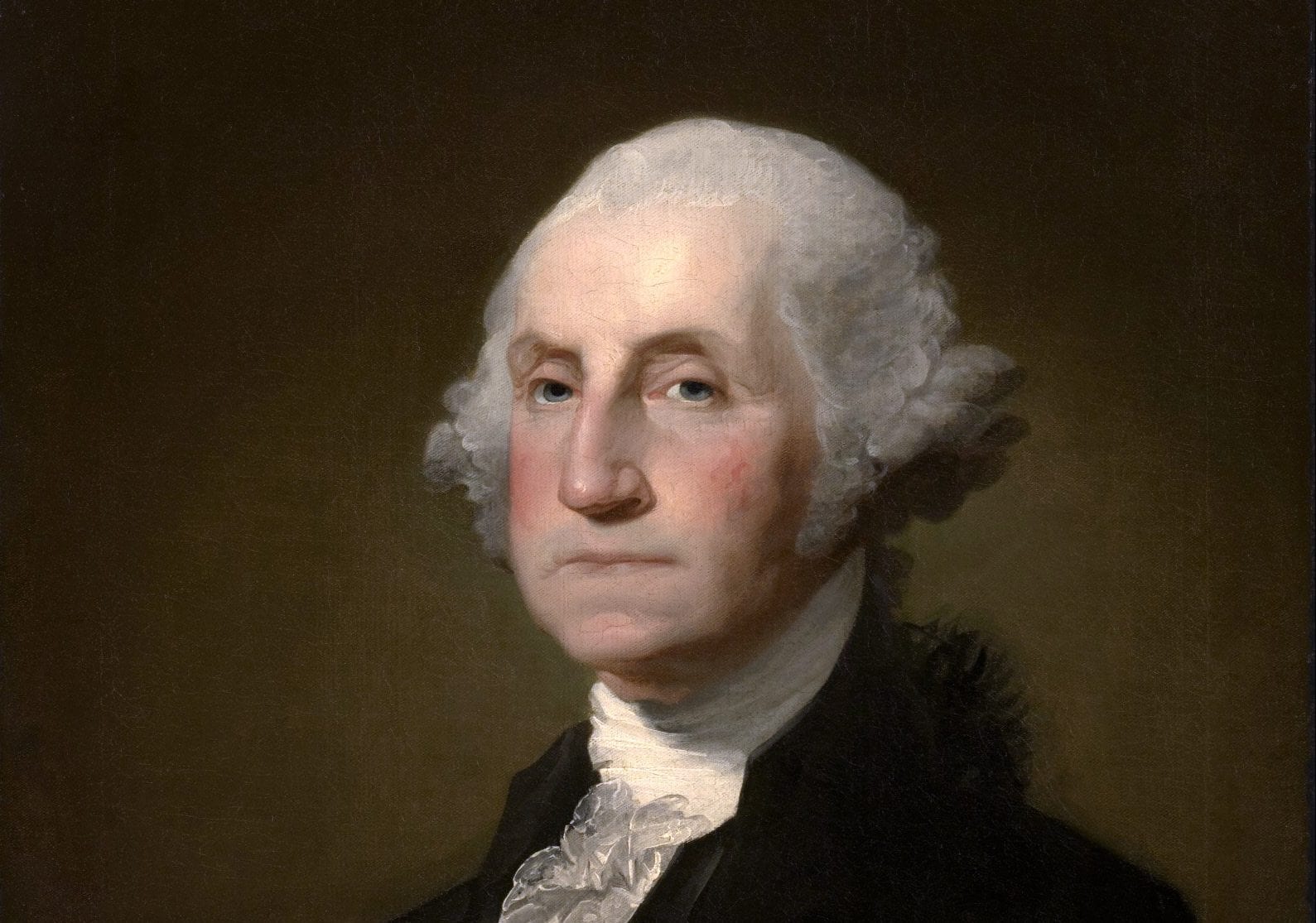

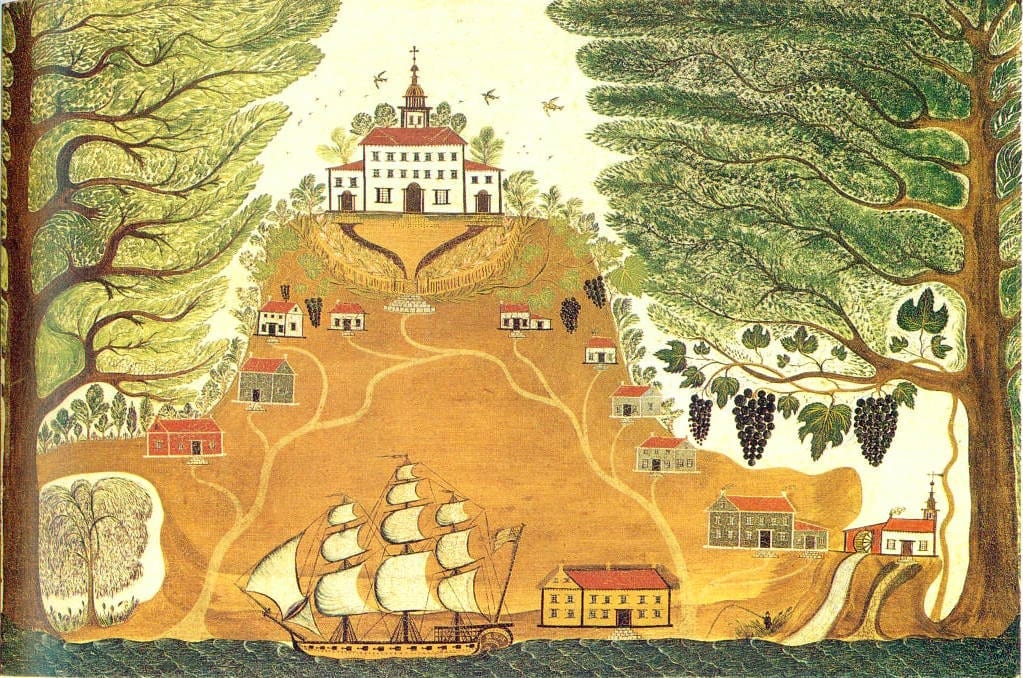

Even in the upper South, the principles of the Declaration worked against slavery, leading to some manumissions. Some slaves also fled their masters during the disruptions of the war for independence. As they had in the decades leading to independence, slaves and free Blacks who could earn money as farmers and skilled artisans continued to buy their freedom or the freedom of family members still enslaved. Masters also manumitted slave children they had fathered and the women who bore them. Manumission and self-manumission also happened in the lower South (South Carolina and Georgia), although was less frequent there (Envisioning an African American Regiment (1778)).

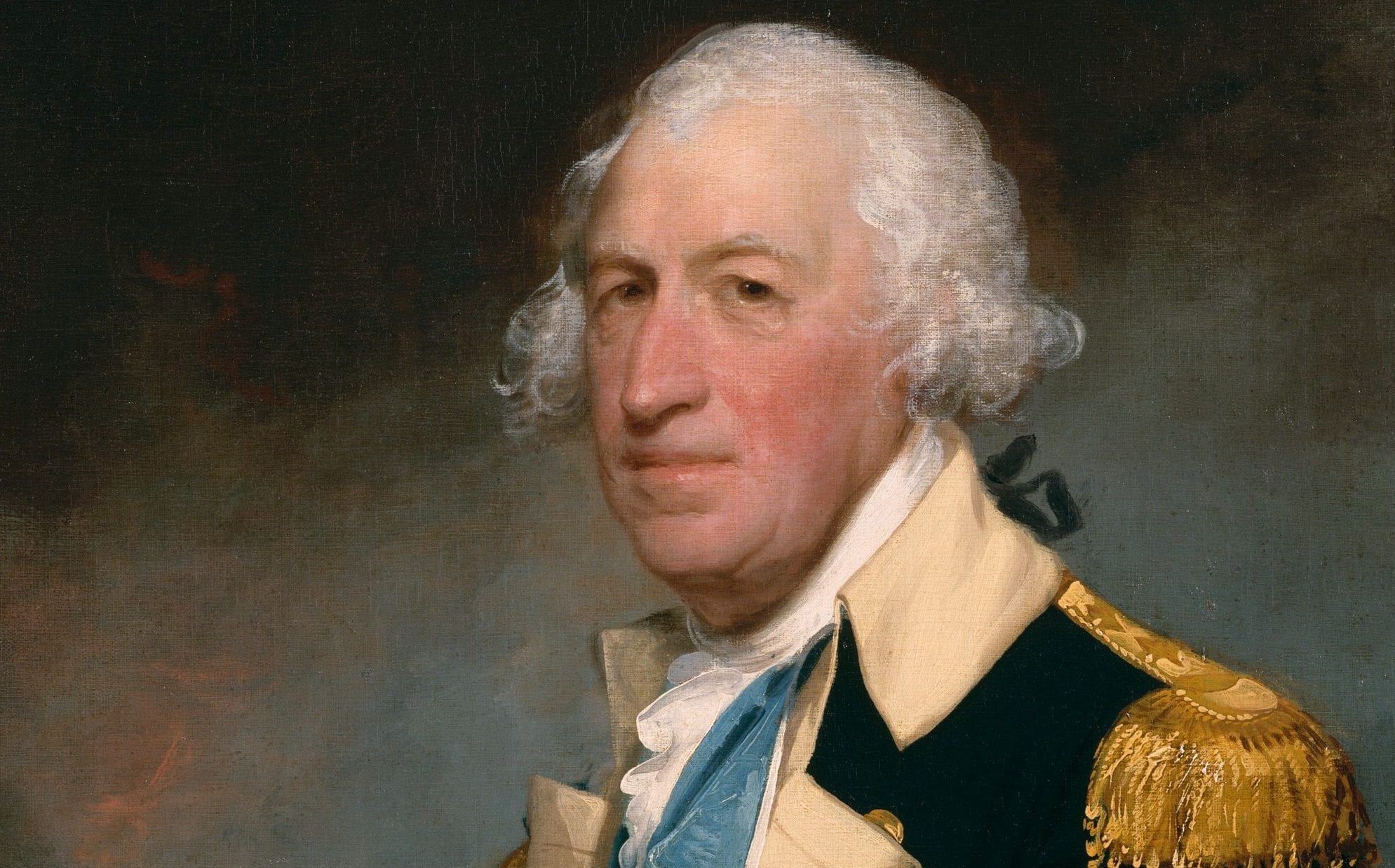

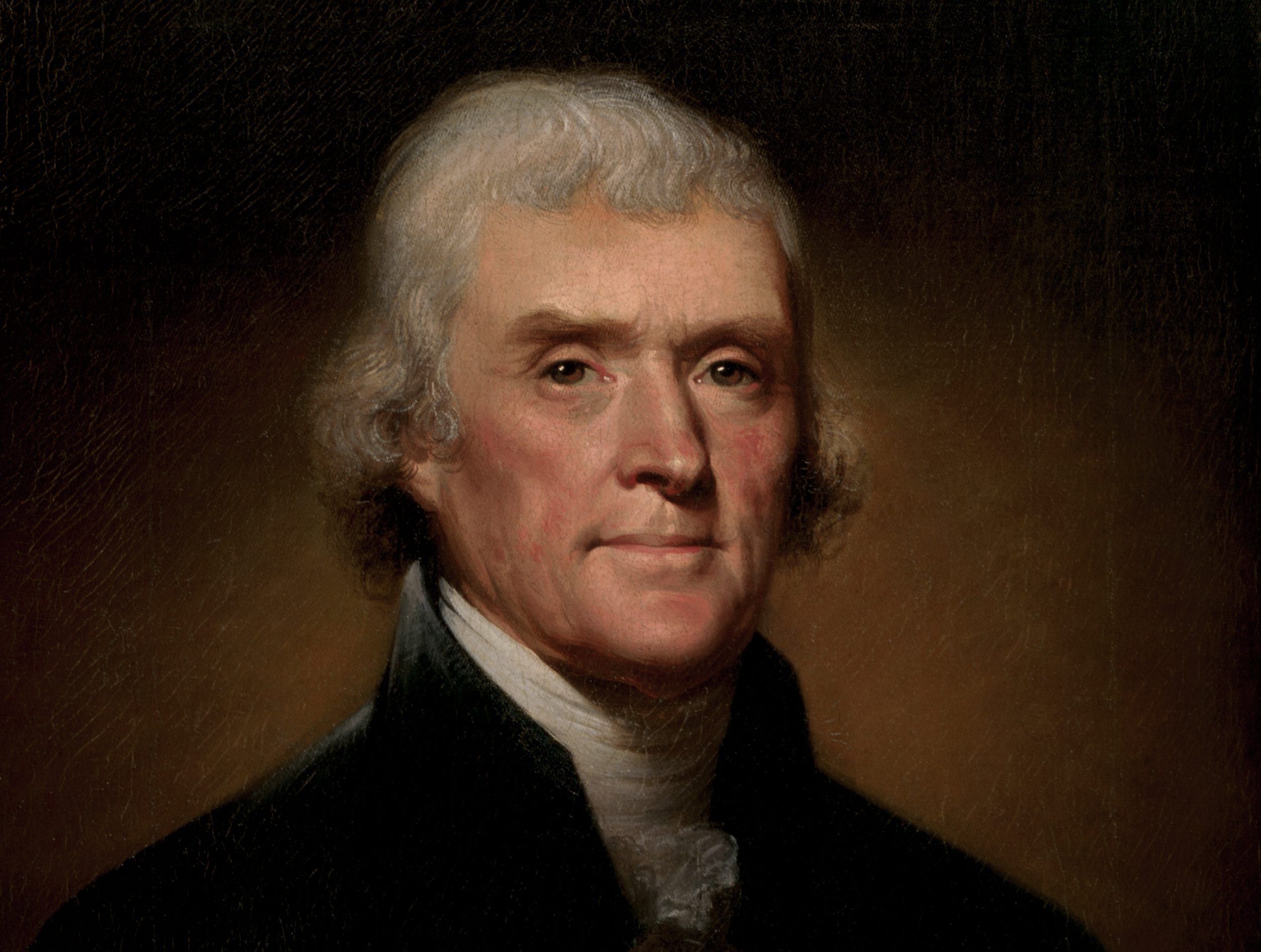

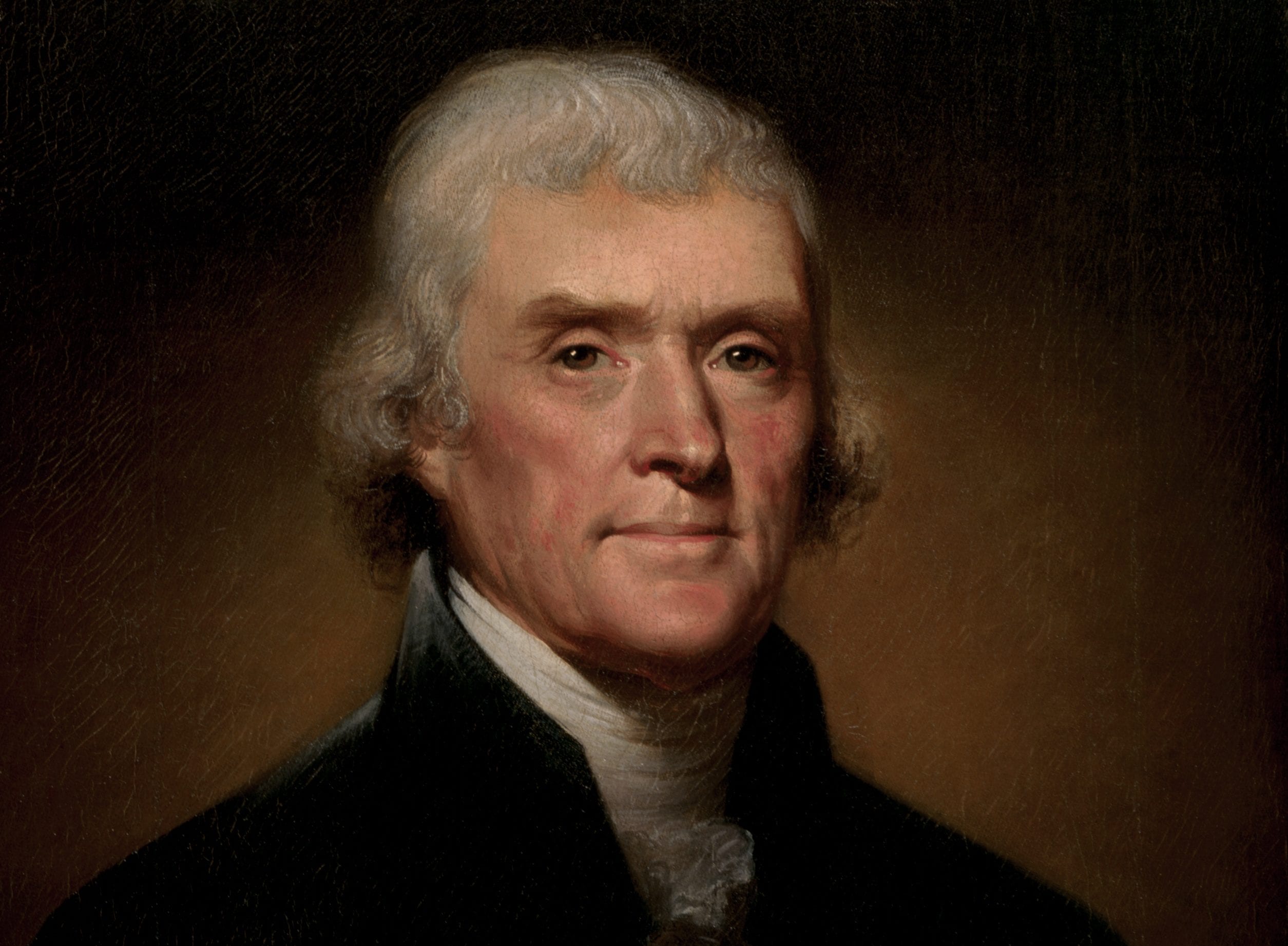

On the national level, Thomas Jefferson proposed for the Ordinance of 1784 a clause banning slavery in all land west of the Appalachians and east of the Mississippi River. The provision failed by a single vote in the Confederation Congress, setting the stage for the eventual expansion of slavery into the future states of Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi-and later Louisiana, Missouri, and Texas. “Thus we see the fate of millions unborn hanging on the tongue of one man,” Jefferson observed, “and heaven was silent in that awful moment.”