Introduction

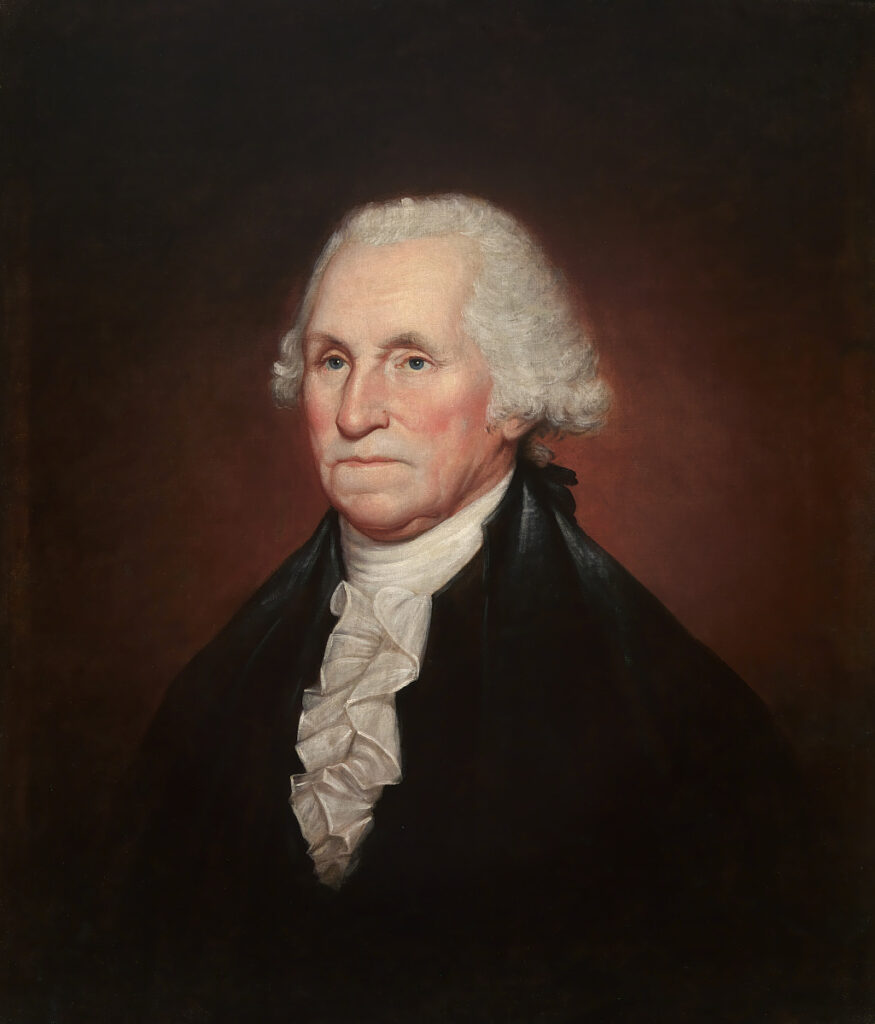

When news of the Treaty of Paris reached America in November 1783, much of the British army had already set sail from New York. Meanwhile, the Continental Army had been disbanding since June, when George Washington (1732–1799), to cut costs for the cash-strapped Confederation Congress, furloughed two-thirds of his troops. On November 25, as the last British regiments evacuated Manhattan, Washington and what remained of his army arrived in the city. On December 4 he said farewell to his officers during an emotional banquet at Fraunces Tavern, then walked past assembled infantrymen to a dock where a barge waited to ferry him across the Hudson. From New Jersey, he made his way south to Annapolis, Maryland, where Congress was in session.

Celebrations slowed his journey as communities through which he passed detained him for banquets and balls in his honor. On December 20, he arrived in Annapolis, sending a note to Thomas Mifflin (1744–1800), president of Congress, asking “in what manner it will be most proper to offer my resignation.” Congressmen Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) and Elbridge Gerry (1744–1814) prepared a document orchestrating Washington’s appearance before Congress, which was set for noon on December 23. As scripted, after Washington was escorted into what is now the Old Senate Chamber of the Maryland State House, Mifflin informed the commander-in-chief that “Congress, sir, are prepared to receive your communications.” When Washington rose to speak, he bowed to Congress; the members of Congress responded by removing their hats but not bowing—a demonstration of civilian control of the military.

Washington delivered his remarks with calm composure until he arrived at the passage in which he entrusted “the interests of our dearest country to the protection of Almighty God.” Here, his voice cracked as he choked back tears. When Washington regained his composure and finished the speech, it was his audience that felt overcome with emotion. “The spectators all wept,” remembered Maryland Congressman James McHenry (1753–1816), “and there was hardly a member of Congress who did not drop tears.”

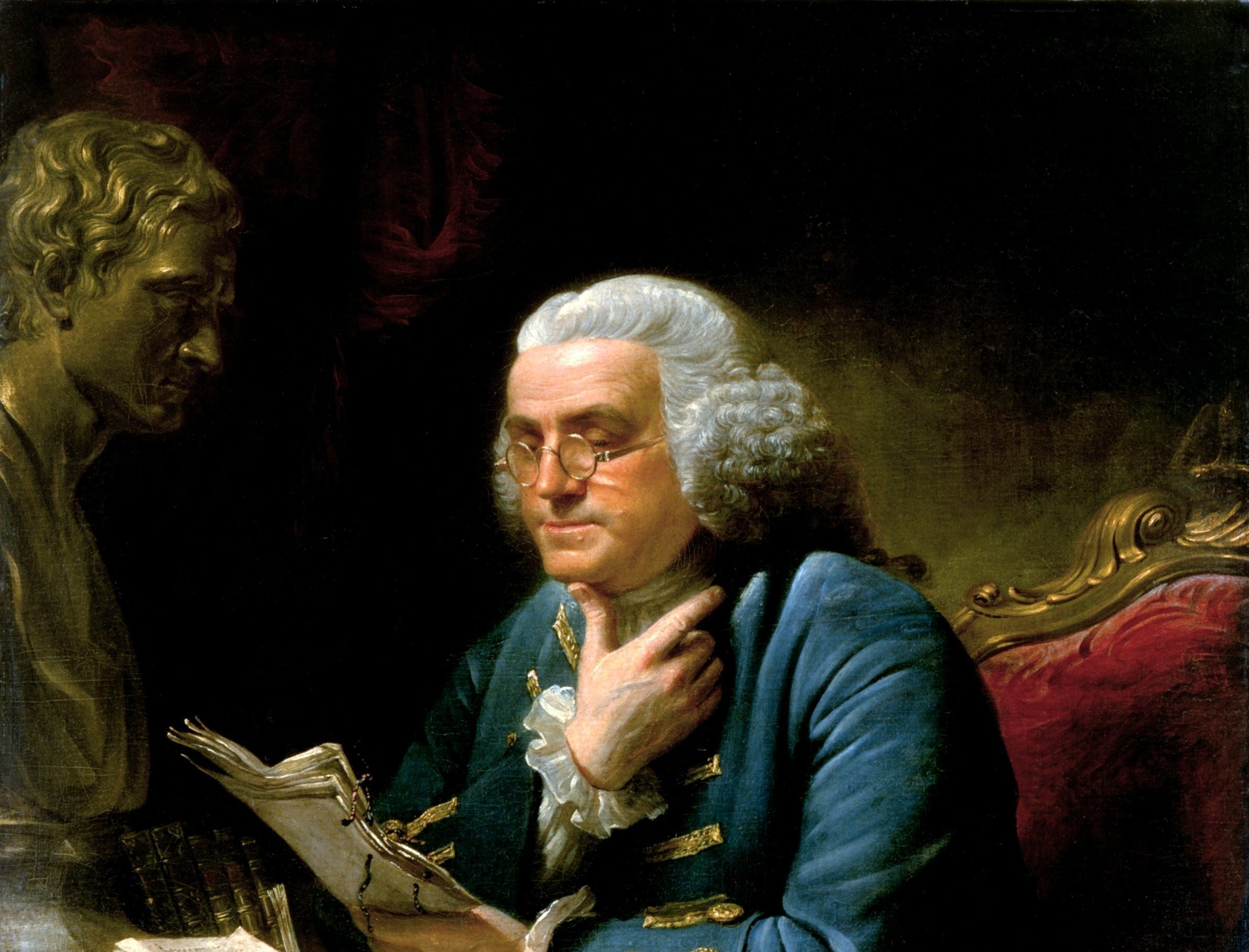

Washington’s resignation caused many to compare him to Cincinnatus (ca. 519–ca. 430 B.C.), the famed Roman statesman entrusted with nearly unlimited power during wartime who achieved swift victory and then returned to private life on his farm. Artist Benjamin West (1738–1820) later reported that King George III (1738–1820) said Washington’s willingness to give up power made him “the most distinguished of any man living” and “the greatest character of the age.”

—Robert M.S. McDonald

The great events on which my resignation depended having at length taken place, I have now the honor of offering my sincere congratulations to Congress and of presenting myself before them to surrender into their hands the trust committed to me, and to claim the indulgence of retiring from the service of my country.

Happy in the confirmation of our independence and sovereignty, and pleased with the opportunity afforded the United States of becoming a respectable nation, I resign with satisfaction the appointment I accepted with diffidence—a diffidence in my abilities to accomplish so arduous a task, which, however, was superseded by a confidence in the rectitude of our cause, the support of the supreme power of the Union, and the patronage of Heaven.

The successful termination of the war has verified the more sanguine expectations, and my gratitude, for the interposition of Providence, and the assistance I have received from my countrymen, increases with every review of the momentous contest.

While I repeat my obligations to the army in general, I should do injustice to my own feelings not to acknowledge in this place the peculiar services and distinguished merits of the gentlemen who have been attached to my person during the war. It was impossible the choice of confidential officers to compose my family should have been more fortunate. Permit me, sir, to recommend in particular those, who have continued in service to the present moment, as worthy of the favorable notice and patronage of Congress.

I consider it an indispensable duty to close this last solemn act of my official life, by commending the interests of our dearest country to the protection of Almighty God, and those who have the superintendence of them, to his holy keeping.

Having now finished the work assigned me, I retire from the great theater of action—and bidding an affectionate farewell to this august body under whose orders I have so long acted, I here offer my commission, and take my leave of all the employments of public life.